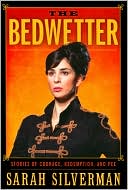

A Futile and Stupid Gesture: How Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever

The ultimate biography of National Lampoon and its cofounder Doug Kenney, this book offers the first complete history of the immensely popular magazine and its brilliant and eccentric characters. With wonderful stories of the comedy scene in New York City in the 1970s and National Lampoon's place at the center of it, this chronicle shares how the magazine spawned a popular radio show and two long-running theatrical productions that helped launch the careers of John Belushi, Bill Murray, Chevy...

Search in google:

The ultimate biography of National Lampoon and its cofounder Doug Kenney, this book offers the first complete history of the immensely popular magazine and its brilliant and eccentric characters. With wonderful stories of the comedy scene in New York City in the 1970s and National Lampoon's place at the center of it, this chronicle shares how the magazine spawned a popular radio show and two long-running theatrical productions that helped launch the careers of John Belushi, Bill Murray, Chevy Chase, and Gilda Radner and went on to inspire Saturday Night Live. More than 130 interviews were conducted with people connected to Kenney and the magazine, including Chevy Chase, John Hughes, P. J. O'Rourke, Tony Hendra, Sean Kelly, Chris Miller, and Bruce McCall. These interviews and behind-the-scene stories about the making of both Animal House and Caddyshack help to capture the nostalgia, humor, and popular culture that National Lampoon inspires. The Capital Times A story that sheds welcome light on some of the funniest material of our age.

\ \ A Futile And Stupid Gesture\ \ \ How Doug Kenney and National Lampoon Changed Comedy Forever\ \ \ \ By Josh Karp\ \ \ CHICAGO REVIEW PRESS\ \ \ Copyright © 2006\ \ Josh Karp\ All right reserved.\ \ ISBN: 1-55652-602-4\ \ \ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ Hayley Mills in Pleasantville \ \ \ "Doug was Doris Day, a Coke and a hamburger." \ -National Lampoon editor Brian McConnachie \ In the 1950s, Chagrin Falls, Ohio, was the kind of place where\ Americans believed that Father Knows Best patriarch Jim Anderson\ could raise Kitten, Bud, and Princess in a big fine home with\ total comfort and domestic bliss on an insurance agent's salary.\ Chagrin Falls was a town where groceries were purchased at\ Greenway's or the A&P. Each fall, moms took their kids to Brewster\ and Church for school clothes and Brondfield's for new shoes, followed\ by a trip to the marble soda fountain at Standard Drug, where\ they washed down ten-cent burgers with the best lemon soda in the\ world. All the stores were closed on Wednesdays and on special\ occasions everyone dressed in church clothes for dinner at Crane's\ Canary Cottage.\ When the blizzard of 1963 crippled Chagrin, local officials roped\ off one neighborhood so children could sled down Grove Hill onto\ Bell Street. During less extreme weather, winter meant skating on\ the frozen Chagrin River where adults kept a bonfire burning on the\ banks to warm little hands.\ On Saturday mornings inthe fall, the Chagrin Falls High School\ Tigers marching band tromped up East Washington Street to the\ Fairgrounds stadium, spreading school spirit through town while\ yards were raked and the sweet, smoky smell of burning leaves filled\ the air. It really was that kind of place.\ "It was like Pleasantville," says Chagrin native Ginna Bourisseau. "I\ was four years old, walking two blocks to buy penny candy by myself.\ Everybody watched out for everybody's kids. That's how safe it was."\ Being an adolescent in Chagrin meant worshipping the football\ players and hoping that someday "Firelord" would be listed among\ your accomplishments in the high school's Zenith yearbook. This\ coveted title mysteriously signified that you were one of the pranksters\ who burned the Tigers' winning score on an opposing team's\ football field in the dark of night, or anonymously painted black\ stripes on the Orange High School mascot. None of this was lost on\ Doug Kenney, who lived in Chagrin Falls from 1958 to 1964. His\ story neither begins nor ends in this midwestern town. Yet it is the\ place that defined him and by which he defined himself.\ "I'm Doug Kenney from Chagrin Falls, Ohio."\ It was that place in the middle of the country whose social dynamics,\ customs, and dreams so influenced and informed his sense of\ humor, self, and place in the world. It was a community that he came\ to remember with both great affection and profound alienation.\ Despite his normal physical appearance, Doug Kenney was an\ outsider in Chagrin Falls-in and from the place, but not of it.\ Rather, he was a quiet observer, cloaked as a normal American kid,\ soaking in the rituals of prom, homecoming, and lusting aimlessly\ after the head cheerleader.\ "We remember everybody, even if they only lived here for six\ months," says Jim Vittek, another Chagrin native. "We remember\ the way they kicked a soccer ball or threw a football. We remember\ where they sat in class."\ Yet in Chagrin Falls, few remember Doug Kenney. It is as if he\ moved through town invisibly, leaving no fingerprints. They remember\ The Carol Burnett Show's Tim Conway instead. He is Chagrin's\ favorite son.\ * * *\ Doug Kenney's story begins in Newport, Rhode Island, where in\ the 1920s and '30s his paternal grandfather, Daniel Kenney, was a\ tennis pro at the Newport Casino Club. Newport, as much as anyplace\ else, was home to this son of a vegetable cart operator whose\ parents emigrated from Ireland.\ Daniel Kenney and his wife, Eleanor, had five children, the eldest\ being Doug's father, Daniel "Harry" Kenney, followed by Bill, Frank,\ Jack (who was killed in World War II), and a daughter, Margaretta.\ Harry was born in Massachusetts in 1915. The rest were born in\ Newport.\ The Kenney family's existence was an itinerant one common\ to club pros of the time-the family usually left Newport the day\ after Thanksgiving for a winter of work in Palm Beach, Florida, and\ returned north on April 15 every year. Palm Beach was the winter\ home of Harold Vanderbilt, where Daniel and his sons taught tennis\ lessons for family and guests each day on specially built courts positioned\ to keep the noonday sun out of Mr. Vanderbilt's eyes, demonstrating\ for Harry precisely how the other half lived. In the fall, the\ Kenneys often found themselves at the Astor estate in Rhinebeck,\ New York, or Aiken, South Carolina-wherever the wealthy needed\ a pro to teach them the game. Arriving at either of these locations,\ Daniel bought the local paper, pulled out the home rental listings,\ and drove his family around looking for a place to live. They would\ never own a home.\ In Newport, the Kenneys were regarded as the "first family of\ tennis," with each of Daniel's sons becoming pros and several uncles\ and cousins teaching professionally. One Kenney or another taught\ the game to Newport summer residents and wealthy vacationers like\ George Plimpton, Treasury Secretary C. D. Dillon, Jacqueline Bouvier,\ and her future husband, John F. Kennedy. Down in Palm Beach,\ it was more of the same, with Frank Kenney helping Woolworth\ heiress Barbara Hutton learn to serve and volley at an exclusive club,\ where the pair would have drinks while music wafted from the trees\ on warm winter afternoons and the sound of members shooting skeet\ on the beach could be heard in the distance.\ Frank and Bill Kenney loved teaching tennis and the life it provided\ them. Neither man minded lower social status in a gilded world.\ It was all they knew and they embraced it. Their oldest brother felt\ differently.\ Barely out of his teens, Harry taught tennis in Dark Harbor,\ Maine; Palm Beach; Newport; Hartford; Cleveland; Philadelphia;\ and elsewhere, yet he always wanted a different life, one more like\ the members than their servants. Harry wasn't happy-go-lucky like\ Frank, who was satisfied with his station in life and amused by the\ social fissures that placed him in the lesser economic class. By contrast,\ Harry was serious, ambitious, and aggressive at everything he\ did-on and off the court. He badly wanted an education. Brooding\ and quiet, he kept personal matters private. Teaching tennis was an\ existence Harry desperately wanted to escape.\ "One day," Harry told Margaretta, "I'll never go in the back\ door again. Only the front."\ In 1935, during a stint at the Hartford Country Club, Harry\ met eighteen-year-old Estelle "Stephanie" Karch, the daughter of an\ Eastern European immigrant iron forger from Chicopee, Massachusetts.\ Harry quickly learned that she was a good cook and fun to be\ around, with an unpretentious attitude, a great sense of humor, and\ an earthy manner. The pair married in Hartford on July 28, 1936,\ without the presence or knowledge of Harry's family. Yet when the\ Kenney clan met Stephanie, they loved her. It was hard not to.\ Around the same time, Harry's forty-five-year-old father contracted\ pneumonia and died three days later with no life insurance\ and little money. Harry and his brother Bill were already out on their\ own, leaving Eleanor Kenney with three children to feed in Newport.\ Frank taught tennis to support the family and Harry sent his mother\ fifty dollars a month.\ On July 21, 1939, Stephanie gave birth to a son they named Daniel\ Vance Kenney, known as Dan. Otherwise healthy, Dan was born\ with spina bifida, which required surgery and some stressful infant\ care. This often debilitating birth defect, however, seemed to have\ little impact on their firstborn, who grew into a handsome, gregarious\ child.\ While he taught tennis all over the country, Harry was always\ in search of other work that would remove him from the servant\ class. In Hartford he joined the Governor's Guard, an elite group\ that protected and traveled with Connecticut's top official. In Reno\ he became a sheriff's deputy, and he did some personnel management\ for a magnesium mine in Las Vegas. While teaching in Philadelphia,\ Harry attended college, probably at night, and got the education he\ so desired.\ Harry and Stephanie's second child, Douglas Clark Francis Kenney,\ was born in West Palm Beach, Florida, on December 10, 1946,\ nearly five years to the day after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor\ and America entered its defining war.\ Born in a nation flush with patriotism from defeating evil, he\ was named for Douglas MacArthur, the legendary pipe-chomping\ five-star general who commanded the U.S. forces in Southeast Asia\ and received the formal Japanese surrender that effectively ended\ the war.\ "I was a kind of monument to a general who brought us yellow\ imperialism," Doug told a reporter years later.\ Doug was an uncommonly bright and sensitive child with atrocious\ eyesight. At the age of seven, Doug told a friend, Stephanie\ took him to an eye doctor for the first time. Fitted with his first pair\ of glasses, he recalled the drive home vividly, as every vein in every\ leaf seemed to be apparent from the backseat window of his mother's\ car; each blade of grass individual, distinct, and a rich, shimmering\ green. It was as if he were truly seeing the world for the first time-in\ Technicolor-in detail so intense that it gave him a headache.\ "He was unique from birth," Victoria "Vicky" Kenney, Doug's\ younger sister by seven years, told Harvard Magazine.\ In the early 1950s, the Kenneys settled in Mentor, Ohio, where\ Harry was a tennis pro at the Kirtland Country Club. Dan was a tall,\ charming boy at Riverside High School-admired by everyone who\ knew him. Harry and Stephanie, it seemed, couldn't get enough of\ their oldest child.\ "Dan was really well liked by his parents," says family friend Bill\ Tienvieri. "I can see how Doug might have resented that a little."\ If he did, however, it was hardly apparent, as Doug looked up\ to his all-American brother when he wasn't devouring books, radio,\ and comics. Filled with these images, Doug's overactive imagination\ kept him up late at night, unable to sleep for all the thoughts racing\ through his head.\ Kid sister Vicky was a cute, pig-tailed blond, both very smart and\ very sweet. Doug adored her. The three children all filled familiar\ roles: Dan the family hero and golden boy; Doug the most sensitive,\ thoughtful, and eager-to-please child; and Vicky the mascot. They\ were, to all who knew them, a model midwestern, suburban family\ on an upward trajectory.\ In the late 1950s, Harry moved the family to Chagrin Falls after\ a Kirtland member who sat on the board of Diamond Alkaloid in\ nearby Painesville recommended him for a job in the company's personnel\ department. Entering the corporate world, he finally left the\ servant class for good. Dan had just graduated from high school,\ Doug was twelve, and Vicky was five.\ The Kenneys settled in a small ranch home on Bell Road in unincorporated\ South Russell (considered part of Chagrin Falls). Harry\ remained serious and quiet, and Stephanie was always charming, a\ quick-witted woman who loved a party. Their best friends in town\ were Don Martin, the new pro at Kirtland, and his wife, Ruth. By\ the time he was in high school, Doug would string rackets for Martin\ at Kirtland during the summer, soaking in, as Harry once had, the\ contrast between his life and that of the members.\ In fall 1958, Dan headed to Kent State University where he\ became extremely popular, joined the Delta Tau Delta fraternity, and\ was known campus-wide as "Dan the Delt." Back in Chagrin Falls,\ Doug played the role of bookish, well-mannered little brother.\ "Doug and I were friends during his brief stay in Chagrin Falls,"\ says Tom Luckay. "We attended eighth grade together [at the Chagrin\ Falls junior high], and I remember him as a very intelligent and\ polite young man, which impressed my parents. I don't remember\ much about his sense of humor. I do remember that as suddenly as he\ emerged, he disappeared.... I may have been one of his only close\ friends during his stay in Chagrin Falls."\ In junior high, Doug began to see that he possessed both an\ innate gift for humor and intellectual capabilities that exceeded those\ of his peers-and often his teachers. In the cafeteria, he rearranged\ the letters on the menu board to read "scrambled snails." In the classroom,\ he showed an aptitude for parroting the precise style, cadence,\ and expression of the writers he was asked to read. This took the\ form of papers about Huckleberry Finn, written in the manner of\ Twain, aping his voice and style. Teachers graded him up or down\ according to whether they thought he was a wiseass or a genius.\ Perhaps some of them didn't understand what he was doing. Nor,\ necessarily, did Doug, who may have simply channeled what he read\ into his writing without any preconceived plan.\ During summer 1959, Dan Kenney's car overturned and he was\ rushed to the hospital, where doctors discovered serious problems\ with his bladder and kidneys, possibly stemming from his bout with\ spina bifida. Though he returned to Kent State that fall, joining the\ Phi Gamma Delta house and ROTC, Dan's diseased kidneys plagued\ him from that point forward, drawing even greater attention and\ affection from his parents.\ Given Doug's facility with language and academic abilities, Harry\ and Stephanie concluded that they had "a winner" and offered him\ the choice for high school between the well-established and very\ preppy University School nearby or Gilmour Academy, a fifteen-year-old,\ all-boys, Catholic prep school in neighboring Gates Mill. Doug\ chose Gilmour.\ "University School was full of WASPs and epitomized that culture,"\ says Jim Schuerger, a Gilmour teacher who grew close to Doug\ and his family. "Doug would have pushed them beyond where he\ could indulge his wit."\ Thus, on the 143-acre Gilmour campus, where the Holy Cross\ Brothers sought to create a disciplined environment for Catholic\ youth, Doug Kenney began to come out of his shell. Though neither\ loud nor boisterous, he was going through puberty and ready to discover\ his identity as a teenage boy-a smart, funny one.\ * * *\ Ivo Regan was known as "Mr. Gilmour." Given to wearing berets\ and leaning on a cane, he was the school's befrocked equivalent of\ Robin Williams in Dead Poets Society. Regan was an erudite, sophisticated,\ alcoholic, Holy Cross Brother from a shitty Nebraska cattle\ town, and likely a repressed homosexual. An extraordinary English\ teacher, Regan was tall, lean, intense, tortured, and explosive. Spencer\ Tracy's Father Flanagan he was not.\ In fall 1960, Doug Kenney was a freshman assigned to Regan's\ English class, where the teacher frequently stood on the table to\ dramatically make a point and gave student assignments such as\ "five hundred words describing the inside of a ping-pong ball" that\ stopped most of them dead in their tracks.\ On the first day of class, Regan asked students to write an\ essay from the perspective of an apple, describing life as a piece of\ fruit. Save Doug, it had the desired effect on the entire class, who\ returned with little more than some incoherent, fearful responses.\ When the assignment came due, Regan went around the classroom\ asking each student to read his piece. Arriving at Doug, he was\ amazed to hear the skinny, bespectacled boy read a funny, insightful,\ and well-conceived essay from the perspective of a neurotic apple.\ "I didn't even know what neurotic meant," recalls Doug's classmate\ John Mulligan.\ Kenney and Regan became kindred spirits, a mentor and student\ who would walk across broken glass for each other. Admiring and\ identifying with the polite but rebellious fourteen-year-old, Regan\ sought to encourage, push, and protect Doug any way he could, all\ while exposing him to the wider world. Through Regan, Doug grew\ to love Graham Greene, Gerard Manley Hopkins, James Thurber,\ and particularly Evelyn Waugh, who would become his idol and\ against whose work he would one day measure his own. Moreover,\ Regan taught Doug how to use language economically and for maximum\ impact. Regan exposed Doug to the idea that the world was not\ as it appeared and that darkness coexisted with the light pervading\ the American landscape of Chagrin Falls. Though Doug had likely\ suspected this, it was not something that Harry or Stephanie was\ going to teach him. Yet it was squarely in keeping with the opposing\ forces that battled within his brain.\ "There was a poem that Brother Ivo made a big deal out of when\ we were students at Gilmour," says Jerry Murphy, president of Doug's\ class. "It was 'Buffalo Bill's Defunct' [by e. e. cummings]. I recall the\ last line, 'how do you like your blueeyed boy Mister Death.'"\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from A Futile And Stupid Gesture\ by Josh Karp\ Copyright © 2006 by Josh Karp.\ Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.\ \

ContentsAcknowledgmentsIntroduction: Midas at the Marmont1 Hayley Mills in Pleasantville2 The Most Perfect WASP3 Here Is New York4 You’ve Got a Weird Mind. You’ll Fit in Well Here5 What Do Women Eat?6 Hitler Being Difficult7 Show Biz and Dead Dogs8 Guns and Sandwiches9 The Pirates10 The Cultural Revolution11 Fuck the Proposal12 Round Up the Usual Jews13 Pheasant Shake for Mr. Kenney14 A Year with No Spring EpilogueBibliographyIndex

\ American Way"Karp makes a persuasive case for Kenney to be considered among the key architects of post-World War II humor."\ \ \ \ \ Booklist"Karp's account of Kenney's death is as moving as the excerpts from excellent NL articles are hilarious."\ \ \ Steve Goddard's History WireFilled with anecdotes that will send tears streaming down the readers' cheeks.\ \ \ \ \ The Capital TimesA story that sheds welcome light on some of the funniest material of our age.\ \ \ \ \ Virginia HeffernanPlenty of goateed comedy writers, Harvard Lampoon veterans and Hollywood people in Brioni suits still mist up at the memory of Kenney, the raffish humor whiz who helped start National Lampoon in 1970, helped write "Animal House" and "Caddyshack" and then fell or jumped off a cliff in Hawaii in 1980. He definitely had one blowout decade. But from his parodies and japes, which have dated unevenly, as well as his life's erratic plot points, it's hard to get exactly why people thought he was so cool. Even A Futile and Stupid Gesture, Josh Karp's painstaking argument for his supergenius, doesn't close the case.\ —The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyScreenwriter Kenney (Animal House; Caddyshack), co-founder of National Lampoon, was one of the gifted gagsters who ignited the 1970s revolution in American humor. Journalist Karp (Playboy; Premiere) delivers an iridescent, polychromatic portrait of the humorist, framed within an amusing anecdotal history of National Lampoon. To chart the magazine's rise and fall, Karp conducted 150 interviews, mapping every avenue of business decisions, feuds, romances, cocaine use and bizarre pranks. It all began at Harvard, where wild wit Kenney and misanthropic Henry Beard became "symbiotic creative forces," revitalizing the Harvard Lampoon. When they teamed with publisher Matty Simmons, National Lampoon was born in 1970, filling the "gigantic void" between the New Yorker and Mad. Success led to heightened hilarity as the brand expanded with posters, products, theatrical productions and recordings. The 1973 National Lampoon Radio Hour cast resurfaced in 1975 on Saturday Night Live, but the anarchic Animal House in 1978 catapulted Kenney to Hollywood-as Karp writes, "He had transformed himself from nerd to preppy to hippie and now to unassuming millionaire artiste." 16-page b&w photo insert not seen by PW. (Sept. 1) Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ BooklistKarp's account of Kenney's death is as moving as the excerpts from excellent NL articles are hilarious.\ \ \ \ \ Richard RoeperThe definitive profile of Kenney's brilliant comic mind and his too-short life. \ — Chicago Sun-Times\ \ \ \ \ The New York TimesJammed with personalities and capsule histories.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalFor the multitude of baby boomers coming into full adolescent bloom in the 1970s, the National Lampoon was the cat's ass. With comedic masterpieces like the 1964 Kefauver High School Yearbook parody and the transcendent January 1973 cover of the buy-this-magazine-or-we'll-shoot-this-dog issue, the Lampoon imprinted American popular culture forever. The Harvard-educated mastermind behind the Lampoon, as well as the movies Animal House and Caddyshack, was Doug Kenney, whose story and intersections with other star-crossed geniuses like Michael O'Donoghue, John Belushi, Chevy Chase, and P.J. O'Rourke are wonderfully told in this interview-driven, behind-the-scenes account. Readers are immersed in the comedy scene in 1970s New York City as well as the birth of the Lampoon and its spin-off media. Karp, an experienced journalist, conducted 150 interviews, so it's understandable that the story's cadence is at times more staccato than fluid. Like a cultural joyride in a 1975 Cutlass 442-fun, fast, and furious. Larger public and academic libraries should purchase.-Barry X. Miller, Austin P.L., TX Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.\ \