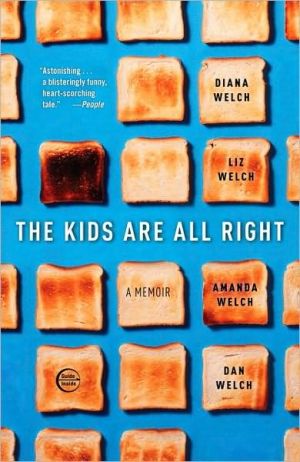

A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True Story

Well, this was when Bill was sighing a lot. He had decided that after our parents died he just didn't want any more fighting between what was left of us. He was twenty-four, Beth was twenty-three, I was twenty-one, Toph was eight, and all of us were so tried already, from that winter. So when something world come up, any little thing, some bill to pay or decision to make, he would just sigh, his eyes tired, his mouth in a sorry kind of smile. But Beth and I...Jesus, we were fighting with...

Search in google:

Well, this was when Bill was sighing a lot. He had decided that after our parents died he just didn't want any more fighting between what was left of us. He was twenty-four, Beth was twenty-three, I was twenty-one, Toph was eight, and all of us were so tried already, from that winter. So when something world come up, any little thing, some bill to pay or decision to make, he would just sigh, his eyes tired, his mouth in a sorry kind of smile. But Beth and I...Jesus, we were fighting with everyone, anyone, each other, with strangers at bars, anywhere -- we were angry people wanting to exact revenge. We came to California and we wanted everything, would take what was ours, anything within reach. And I decided that little Toph and I, he with his backward hat and long hair, living together in our little house in Berkeley, would be world-destroyers. We inherited each other and, we felt, a responsibility to reinvent everything, to scoff and re-create and drive fast while singing loudly and pounding the windows. It was a hopeless sort of exhilaration, a kind of arrogance born of fatalism, I guess, of the feeling that if you could lose a couple of parents in a month, then basically anything could happen, at any time -- all bullets bear your name, all cars are there to crush you, any balcony could give way; more disaster seemed only logical. And then, as in Dorothy's dream, all these people I grew up with were there, too, some of them orphans also, most but not all of us believing that what we had been given was extraordinary, that it was time to tear or break down, ruin, remake, take and devour. This was San Francisco, you know, and everyone had some dumb idea -- I mean, wicca? -- and no one there would tell you yours was doomed. Thus the public nudity, and this ridiculous magazine, and the Real World tryout, all this need, most of it disguised by sneering, but all driven by a hyper-awareness of this window, I guess, a few years when your muscles are taut, coiled up and vibrating. But what to do with the energy? I mean, when we drive, Toph and I, and we drive past people, standing on top of all these hills, part of me wants to stop the car and turn up the radio and have us all dance in formation, and part of me wants to run them all over. Onion AV Club - Joshua Klein Memoirs are tricky for any author to tackle. Inherently narcissistic, the triumphs described are too often boastful and the tragedies too often exploitative. Dave Eggers knows this: The first 30 pages of his book--the preface, which Eggers tells impatient readers to skip--provide an incisive and hilarious dissection of the 300-plus fast pages that follow. It's clear from the elaborate pre-preface bibliographical information that this is no ordinary memoir. Rather, the (mostly) non-fictional A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius is a postmodern memoir in the mold of Laurence Sterne's fictional The Life And Opinions Of Tristram Shandy, a meta-narrative that turns in upon itself and tricks the reader almost every chance it gets. Eggers, one of the founders of the much-missed Might magazine, has seen enough death in his short life (including the faked murder of former child star Adam Rich) to fill such an experience-fueled endeavor, but the way he goes about doing it is what makes Staggering Genius work. When he was 21, both his parents died of cancer, and with his older brother out of the house and his sister in school, he was put in charge of his 8-year-old brother Toph. Instead of wallowing in guilt or depression, Eggers handles tragedy with sheer audacity, finding humor in the most dire situations and refusing to resort to self-pity. He and Toph live the perverse, parents-free fantasy many children fleetingly harbor, with Eggers sharing his bad habits even as he's forced to assume most of the responsibilities. The writing is never quite as clever or novel as in the virtuoso preface, but Eggers constantly finds ways to make even standard self-analysis interesting. At one point, a bedtime conversation with his younger brother morphs into a psychoanalytic session, with Toph suddenly wresting away the proxy-father-figure position and addressing Eggers with omniscient authority. Later, a casting call-back for The Real World (which actually happened) develops into a long confessional about suburban upbringing. The love of minutia and marginalia Eggers brought to Might makes even the most conventional prose inventive; ironically, this includes the relatively rote chronology of the magazine's creation. While Staggering Genius is admittedly uneven, that's paradoxically part of its unpredictable charm: Eggers would never go about things the standard way, and the book--at times both heartbreaking and genius--ably reflects his idiosyncratic, hyper-casual, pop-culture-saturated worldview.

Excerpt from Chapter 1: \ Part 1\ Through the small tall bathroom window the December yard is gray and scratchy, the trees calligraphic. Exhaust from the dryer billows clumsily out from the house and up, breaking apart while tumbling into the white sky.\ The house is a factory.\ I put my pants back on and go back to my mother. I walk down the hall, past the laundry room, and into the family room. I close the door behind me, muffling the rumbling of the small shoes in the dryer, Toph's.\ "Where were you?" my mother says.\ "In the bathroom," I say.\ "Hmph," she says.\ "What?"\ "For fifteen minutes?"\ "It wasn't that long."\ "It was longer. Was something broken?"\ "No."\ "Did you fall in?"\ "No."\ "Were you playing with yourself?"\ "I was cutting my hair."\ "You were contemplating your navel."\ "Right. Whatever."\ "Did you clean up?"\ "Yeah."\ I had not cleaned up, had actually left hair everywhere, twisted brown doodles drawn in the sink, but knew that my mother would not find out. She could not get up to check.\ My mother is on the couch. At this point, she does not move from the couch. There was a time, until a few months ago, when she was still up and about, walking and driving, running errands. After that there was a period when she spent most of her time in her chair, the one next to the couch, occasionally doing things, going out, whatnot. Finally she moved to the couch, but even then, for a while at least, while spending most of her time on the couch, every night at 11 p.m. or so, she had made a point of making her way up the stairs, in her bare feet, still tanned brown in November, slow and careful on the green carpet, to my sister's old bedroom. She had been sleeping there for years -- the room was pink, and clean, and the bed had a canopy, and long ago she resolved that she could no longer sleep with my father's coughing.\ But the last time she went upstairs was weeks ago. Now she is on the couch, not moving from the couch, reclining on the couch during the day and sleeping there at night, in her nightgown, with the TV on until dawn, a comforter over her, toe to neck. People know.\ While reclining on the couch most of the day and night, on her back, my mom turns her head to watch television and turns it back to spit up green fluid into a plastic receptacle. The plastic receptacle is new. For many weeks she had been spitting the green fluid into a towel, not the same towel, but a rotation of towels, one of which she would keep on her chest. But the towel on her chest, my sister Beth and I found after a short while, was not such a good place to spit the green fluid, because, as it turned out, the green fluid smelled awful, much more pungent an aroma than one might expect. (One expects some sort of odor, sure, but this.) And so the green fluid could not be left there, festering and then petrifying on the terry-cloth towels. (Because the green fluid hardened to a crust on the terry-cloth towels, they were almost impossible to clean. So the green-fluid towels were one-use only, and even if you used every corner of the towels, folding and turning, turning and folding, they would only last a few days each, and the supply was running short, even after we plundered the bathrooms, closets, the garage.) So finally Beth procured, and our mother began to spit the green fluid into, a small plastic container which looked makeshift, like a piece of an air-conditioning unit, but had been provided by the hospital and was as far as we knew designed for people who do a lot of spitting up of green fluid. It's a molded plastic receptacle, cream-colored, in the shape of a half-moon, which can be kept handy and spit into. It can be cupped around the mouth of a reclining person, just under the chin, in a way that allows the depositor of green bodily fluids to either raise one's head to spit directly into it, or to simply let the fluid dribble down, over his or her chin, and then into the receptacle waiting below. It was a great find, the half-moon plastic receptacle.\ "That thing is handy, huh?" I ask my mother, walking past her, toward the kitchen.\ "Yeah, it's the cat's meow," she says.\ I get a popsicle from the refrigerator and come back to the family room.\ They took my mother's stomach out about six months ago. At that point, there wasn't a lot left to remove -- they had already taken out [I would use the medical terms here if I knew them] the rest of it about a year before. Then they tied the [something] to the [something], hoped that they had removed the offending portion, and set her on a schedule of chemotherapy. But of course they didn't get it all. They had left some of it and it had grown, it had come back, it had laid eggs, was stowed away, was stuck to the side of the spaceship. She had seemed good for a while, had done the chemo, had gotten the wigs, and then her hair had grown back -- darker, more brittle. But six months later she began to have pain again -- Was it indigestion? It could just be indigestion, of course, the burping and the pain, the leaning over the kitchen table at dinner; people have indigestion; people take Tums; Hey Mom, should I get some Tums? -- but when she went in again, and they had "opened her up" -- a phrase they used -- and had looked inside, it was staring out at them, at the doctors, like a thousand writhing worms under a rock, swarming, shimmering, wet and oily -- Good God! -- or maybe not like worms but like a million little podules, each a tiny city of cancer, each with an unruly, sprawling, environmentally careless citizenry with no zoning laws whatsoever. When the doctor opened her up, and there was suddenly light thrown upon the world of cancer-podules, they were annoyed by the disturbance, and defiant. Turn off. The fucking. Light. They glared at the doctor, each podule, though a city unto itself, having one single eye, one blind evil eye in the middle, which stared imperiously, as only a blind eye can do, out at the doctor. Go. The. Fuck. Away. The doctors did what they could, took the whole stomach out, connected what was left, this part to that, and sewed her back up, leaving the city as is, the colonists to their manifest destiny, their fossil fuels, their strip malls and suburban sprawl, and replaced the stomach with a tube and a portable external IV bag. It's kind of cute, the IV bag. She used to carry it with her, in a gray backpack -- it's futuristic-looking, like a synthetic ice pack crossed with those liquid food pouches engineered for space travel. We have a name for it. We call it "the bag."\ My mother and I are watching TV. It's the show where young amateur athletes with day jobs in marketing and engineering compete in sports of strength and agility against male and female bodybuilders. The bodybuilders are mostly blond and are impeccably tanned. They look great. They have names that sound fast and indomitable, names like American cars and electronics, like Firestar and Mercury and Zenith. It is a great show.\ "What is this?" she asks, leaning toward the TV. Her eyes, once small, sharp, intimidating, are now dull, yellow, droopy, strained -- the spitting gives them a look of constant exasperation.\ "The fighting show thing," I say.\ "Hmm," she says, then turns, lifts her head to spit.\ "Is it still bleeding?" I ask, sucking on my popsicle.\ "Yeah."\ We are having a nosebleed. While I was in the bathroom, she was holding the nose, but she can't hold it tight enough, so now I relieve her, pinching her nostrils with my free hand. Her skin is oily, smooth.\ "Hold it tighter," she says.\ "Okay," I say, and hold it tighter. Her skin is hot.\ Toph's shoes continue to rumble.\ A month ago Beth was awake early; she cannot remember why. She walked down the stairs, shushing the green carpet, down to the foyer's black slate floor. The front door was open, with only the screen door closed. It was fall, and cold, and so with two hands she closed the large wooden door, click, and turned toward the kitchen. She walked down the hall and into the kitchen, frost spiderwebbed on the corners of its sliding glass door, frost on the bare trees in the backyard. She opened the refrigerator and looked inside. Milk, fruit, IV bags dated for proper use. She closed the refrigerator. She walked from the kitchen into the family room, where the curtains surrounding the large front window were open, and the light outside was white. The window was a bright silver screen, lit from behind. She squinted until her eyes adjusted. As her eyes focused, in the middle of the screen, at the end of the driveway, was my father, kneeling.\ It's not that our family has no taste, it's just that our family's taste is inconsistent.\ The wallpaper in the downstairs bathroom, though it came with the house, is the house's most telling decorative statement, featuring a pattern of fifteen or so slogans and expressions popular at the time of its installation. Right On, Neat-O, Outta Sight! -- arranged so they unite and abut in intriguing combinations. That-A-Way meets Way Out so that the A in That-A-Way creates A Way Out. The words are hand-rendered in stylized block letters, red and black against white. It could not be uglier, and yet the wallpaper is a novelty that visitors appreciate, evidence of a family with no pressing interest in addressing obvious problems of decor, and also proof of a happy time, an exuberant, fanciful time in American history that spawned exuberant and fanciful wallpaper.\ The living room is kind of classy, actually -- clean, neat, full of heirlooms and antiques, an oriental rug covering the center of the hardwood floor. But the family room, the only room where any of us has ever spent any time, has always been, for better or for worse, the ultimate reflection of our true inclinations. It's always been jumbled, the furniture competing, with clenched teeth and sharp elbows, for the honor of the Most Wrong-looking Object. For twelve years, the dominant chairs were blood orange. The couch of our youth, that which interacted with the orange chairs and white shag carpet, was plaid -- green, brown and white. The family room has always had the look of a ship's cabin, wood paneled, with six heavy wooden beams holding, or pretending to hold, the ceiling above. The family room is dark and, save for a general sort of decaying of its furniture and walls, has not changed much in the twenty years we've lived here. The furniture is overwhelmingly brown and squat, like the furniture of a family of bears. There is our latest couch, my father's, long and covered with something like tan-colored velour, and there is the chair next to the couch, which five years ago replaced the bloodoranges, a sofa-chair of brownish plaid, my mother's. In front of the couch is a coffee table made from a cross section of a tree, cut in such a way that the bark is still there, albeit heavily lacquered. We brought it back, many years ago, from California and it, like most of the house's furniture, is evidence of an empathetic sort of decorating philosophy -- for aesthetically disenfranchised furnishings we are like the families that adopt troubled children and refugees from around the world -- we see beauty within and cannot say no.\ One wall of the family room was and is dominated by a brick fireplace. The fireplace has a small recessed area that was built to facilitate indoor barbecuing, though we never put it to use, chiefly because when we moved in, we were told that raccoons lived somewhere high in the chimney. So for many years the recessed area sat dormant, until the day, about four years ago, that our father, possessed by the same odd sort of inspiration that had led him for many years to decorate the lamp next to the couch with rubber spiders and snakes, put a fish tank inside. The fish tank, its size chosen by a wild guess, ended up fitting perfectly.\ "Hey hey!" he had said when he installed it, sliding it right in, with no more than a centimeter of give on either side. "Hey hey!" was something he said, and to our ears it sounded a little too Fonzie, coming as it did from a gray-haired lawyer wearing madras pants. "Hey hey!" he would say after such miracles, which were dizzying in their quantity and wonderment -- in addition to the Miracle of the Fish-tank Fitting, there was, for example, the Miracle of Getting the TV Wired Through the Stereo for True Stereo Sound, not to mention the Miracle of Running the Nintendo Wires Under the Wall-to-Wall Carpet So as Not to Have the Baby Tripping Over Them All the Time Goddammit. (He was addicted to Nintendo.) To bring attention to each marvel, he would stand before whoever happened to be in the room and, while grinning wildly, grip his hands together in triumph, over one shoulder and then the other, like the Cub Scout who won the Pinewood Derby. Sometimes, for modesty's sake, he would do it with his eyes closed and his head tilted. Did I do that?\ "Loser," we would say.\ "Aw, screw you," he would say, and go make himself a Bloody Mary.\ The ceiling in one corner of the living room is stained in concentric circles of yellow and brown, a souvenir from heavy rains the spring before. The door to the foyer hangs by one of its three hinges. The carpet, off-white wall-to-wall, is worn to its core and has not been vacuumed in months. The screen windows are still up -- my father tried to take them down but could not this year. The family room's front window faces east, and because the house sits beneath a number of large elms, it receives little light. The light in the family room is not significantly different in the day and the night. The family room is usually dark.\ I am home from college for Christmas break. Our older brother, Bill, just went back to D.C., where he works for the Heritage Foundation -- something to do with eastern European economics, privatization, conversion. My sister is home because she has been home all year -- she deferred law school to be here for the fun. When I come home, Beth goes out.\ "Where are you going?" I usually say.\ "Out," she usually says.\ I am holding the nose. As the nose bleeds and we try to stop it, we watch TV. On the TV an accountant from Denver is trying to climb up a wall before a bodybuilder named Striker catches him and pulls him off the wall. The other segments of the show can be tense -- there is an obstacle course segment, where the contestants are racing against each other and also the clock, and another segment where they hit each other with sponge-ended paddles, both of which can be extremely exciting, especially if the contest is a close one, evenly matched and with much at stake -- but this part, with the wall climbing, is too disturbing. The idea of the accountant being chased while climbing a wall...no one wants to be chased while climbing a wall, chased by anything, by people, hands grabbing at their ankles as they reach for the bell at the top. Striker wants to grab and pull the accountant down -- he lunges every so often at the accountant's legs -- all he needs is a good grip, a lunge and a grip and a good yank -- and if Striker and his hands do that before the accountant gets to ring the bell...it's a horrible part of the show. The accountant climbs quickly, feverishly, nailing foothold after foothold, and for a second it looks like he'll make it, because Striker is so far below, two people-lengths easily, but then the accountant pauses. He cannot see his next move. The next grip is too far to reach from where he is. So then he actually backs up, goes down a notch to set out on a different path and when he steps down it is unbearable, the suspense. The accountant steps down and then starts up the left side of the wall, but suddenly Striker is there, out of nowhere -- he wasn't even in the screen! -- and he has the accountant's leg, at the calf, and he yanks and it's over. The accountant flies from the wall (attached by rope of course) and descends slowly to the floor. It's terrible. I won't watch this show again.\ Mom prefers the show where three young women sit on a pastel-colored couch and recount blind dates that they have all enjoyed or suffered through with the same man. For months, Beth and Mom have watched the show, every night. Sometimes the show's participants have had sex with one another, but use funny words to describe it. And there is the funny host with the big nose and the black curly hair. He is a funny man, and has fun with the show, keeps everything buoyant. At the end the show, the bachelor picks one of the three with whom he wants to go on another date. The host then does something pretty incredible: even though he's already paid for the three dates previously described, and even though he has nothing to gain from doing anything more, he still gives the bachelor and bachelorette money for their next date.\ Mom watches it every night; it's the only thing she can watch without falling asleep, which she does a lot, dozing on and off during the day. But she does not sleep at night.\ "Of course you sleep at night," I say.\ "I don't," she says.\ "Everyone sleeps at night," I say -- this is an issue with me -- "even if it doesn't feel like it. The night is way, way too long to stay awake the whole way through. I mean, there have been times when I was pretty sure I had stayed up all night, like when I was sure the vampires from Salem's Lot -- do you remember that one, with David Soul and everything? With the people impaled on the antlers? I was afraid to sleep, so I would stay up all night, watching that little portable TV on my stomach, the whole night, afraid to drift off, because I was sure they'd be waiting for just that moment, just when I fell asleep, to come and float up to my window, or down the hall, and bite me, all slow-like..." She spits into her half-moon and looks at me.\ "What the hell are you talking about?"\ In the fireplace, the fish tank is still there, but the fish, four or five of those bug-eyed goldfish with elephantiasis, died weeks ago. The water, still lit from above by the purplish aquarium light, is gray with mold and fish feces, hazy like a shaken snow globe. I am wondering about something. I am wondering what the water would taste like. Like a nutritional shake? Like sewage? I think of asking my mother: What do you think that would taste like? But she will not find the question amusing. She will not answer.\ "Would you check it?" she says, referring to her nose.\ I let go of her nostrils. Nothing.\ I watch the nose. She is still tan from the summer. Her skin is smooth, brown.\ Then it comes, the blood, first in a tiny rivulet, followed by a thick eel, venturing out, slowly. I get a towel and dab it away.\ "It's still coming," I say.\ Her white blood cell count has been low. Her blood cannot clot properly, the doctor had said the last time this had happened, so, he said, we can have no bleeding. Any bleeding could be the end, he said. Yes, we said. We were not worried. There seemed to be precious few opportunities to draw blood, with her living, as she did, on the couch. I'll keep sharp objects out of proximity, I had joked to the doctor. The doctor did not chuckle. I wondered if he had heard me. I considered repeating it, but then figured that he had probably heard me but had not found it funny. But maybe he didn't hear me. I thought briefly, then, about supplementing the joke somehow, pushing it over the top, so to speak, with the second joke bringing the first one up and creating a sort of one-two punch. No more knife fights, I might say. No more knife throwing, I might say, heh heh. But this doctor does not joke much. Some of the nurses do. It is our job to joke with the doctors and nurses. It is our job to listen to the doctors, and after listening to the doctors, Beth usually asks the doctors specific questions -- How often will she have to take that? Can't we just add that to the mix in the IV? -- and then we sometimes add some levity with a witty aside. From books and television I know to do this. One should joke in the face of adversity; there is always humor, we are told. But in the last few weeks, we haven't found much. We have been looking for funny things, but have found very little.\ "I can't get the game to work," says Toph, who has appeared from the basement. Christmas was a week ago, and we got him a bunch of new games for the Sega.\ "What?"\ "I can't get the ...

Rules and Suggestions for Enjoyment of This BookviiPreface to This EditionixAcknowledgmentsxxiIncomplete Guide to Symbols and MetaphorsxxxviiiPart I.Through the small tall bathroom window, etc.1ScatologyVideo gamesBlood"Blind leaders of the blind" [Bible]Some violenceEmbarrassment, naked menMappingPart II.Please look. Can You see us, etc.47CaliforniaOcean plunging, frothingLittle League, black mothersRotation and substitutionHills, views, roofs, toothpicksNumbing and sensationJohnny BenchMotionPart III.The enemies list, etc.71DemotionTeachers driven before usMenuPlane crashLightKnifeState of the Family Room AddressHalf-cantaloupesSo like a fragile girlOld model, new modelBob Fosse PresentsPart IV.Oh I could be going out, sure105But no. No no!The weightSeven years one's senior, how fittingJohn DoeDecay v. preservationBurgundy, boltsPart V.Outside it's blue-black and getting darker, etc.123Stephen, murderer, surelyThe BridgeJon and Pontius PilateJohn, Moodie, et al.LiesA stolen walletThe 99th percentileMexican kidsLineups, lightsA trail of blood, and then silencePart VI.When we hear the news at First167[Some mild nudity]All the hope of history to dateAn interviewDeath and suicideMistakesKeg beerMr. TSteve the Black GuyA death faked, perhaps (the gray car)A possible escape, via rope, of sheetsA broken doorBetrayal justifiedPart VII.Fuck it. Stupid show, etc.239Some bitterness, some calculationOr anything that looks un-usMore nudity, still mildOf color, who is of color?Chakka the PakuniHairy all the crotches are, bursting from panties and briefsThe MarinaThe flying-object maneuverDrama or blood or his mouth foaming orA hundred cymbalsWould you serve them grapes? Would that be wrong?"So I'm not allowed"Details of all this will be goodPart VIII.We can't do anything about the excrement281The Future"Slacker? Not me," laughs HillmanMeath: Oh yeah, we love that multicultural stuffFill out forms"a nightmare WASP utopia"A sexual sort of lushnessThere has been Spin the Bottle"I don't know""Thank you, Jesus""I'm dying, Shal"Part IX.Robert Urich says no. We were so close311Laura Branigan, Lori Singer, Ed Begley, Jr.To be thought of as smart, legitimate, permanent. So you do your little thingA bitchy little thing about herA fallThe halls, shabbily shiny, are filled with people in small clumpsThat Polly Klaas guy giving me the finger at the trialAdam, by association, unimpressivePart X.Of course it's cold353The cold when walking off the planePlans for a kind of personal archaeological orgy or something, from funeral homes to John Hussa, whose mom heated milk once, after GrizzlyWeddingsA lesbian agnostic named Minister LovejoyChad and the copiesLeaf pileAnother threatOf course she knowsWouldn't everyone be able to tell?The water rising, as if under it alreadyPart XI.Black Sands Beach is407No handsDown the hill, the walkNot NAMBLABirthday, parquetSkyeHot, poisoned bloodJail, bail, the oracleMore maneuversA fightFinally, finally

\ From Barnes & NobleThe Barnes & Noble Review\ It's an all-too-rare book that can be said to break new ground, but Dave Eggers's A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius does just that. Rather than take its place in what is now a seemingly unending queue of memoirs by people whose lives have been altered by tragic events, tough times, and difficult lessons, Eggers's book starts a new line altogether, one that very few authors will be allowed to join. \ Yes, Eggers lost both his parents to cancer within a matter of months when he was only 22, and yes, it is left to him (with the aid of his older sister and, to a lesser degree, his older brother) to raise his eight-year-old brother. Yes, he and Toph pick up and move from their Chicago-area hometown to the San Francisco Bay region (as though their lives had not already been seen enough disruption), where Eggers fashions for Toph a safe -- which is not to say traditional -- environment. But the reader who buys this book expecting a sort of "Party of Two" soap opera is bound to be disappointed. And those looking for a good cry would be well advised to look elsewhere, too.\ Which is not to say that this work is not...well, heartbreaking. But Eggers avoids the bathos so often associated with the "I got it bad and that ain't good" school of memoir-writing. You'll laugh as often as you cry, perhaps more often, and even when Eggers does focus on the grieving and sense of loss he and his siblings naturally endured, his thoughtful, introspective approach avoids navel-gazing. He's as hard on himself as on anyone else (well, almost), and that frank self-assessment serves the book well.\ Eggers's deft blend of outrageously amusing tales and implied social commentary is also winning. We follow his progress as he strives to be a part of the San Francisco cast of MTV's "Real World" (a goal he is more than a little conflicted about), as he and a small but intrepid group of friends with little combined experience and even less capital launch a magazine intended to change forever the world of periodical publishing, and even, on occasion, as he tries to get over on a young woman.\ But it all works, and in a fashion quite unlike anything you've ever read before. You'll likely begin the book thinking the title an amusing and ironic overstatement, but by the time you've finished reading it, you might just decide, as I did, that it is instead an admirable example of truth in packaging.\ --Brett Leveridge\ \ \ \ \ \ James PoniewozikA Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genuis is a sad yet high-spirited story. \ — Times\ \ \ Joshua KleinMemoirs are tricky for any author to tackle. Inherently narcissistic, the triumphs described are too often boastful and the tragedies too often exploitative. Dave Eggers knows this: The first 30 pages of his book--the preface, which Eggers tells impatient readers to skip--provide an incisive and hilarious dissection of the 300-plus fast pages that follow. It's clear from the elaborate pre-preface bibliographical information that this is no ordinary memoir. Rather, the (mostly) non-fictional A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius is a postmodern memoir in the mold of Laurence Sterne's fictional The Life And Opinions Of Tristram Shandy, a meta-narrative that turns in upon itself and tricks the reader almost every chance it gets. Eggers, one of the founders of the much-missed Might magazine, has seen enough death in his short life (including the faked murder of former child star Adam Rich) to fill such an experience-fueled endeavor, but the way he goes about doing it is what makes Staggering Genius work. When he was 21, both his parents died of cancer, and with his older brother out of the house and his sister in school, he was put in charge of his 8-year-old brother Toph. Instead of wallowing in guilt or depression, Eggers handles tragedy with sheer audacity, finding humor in the most dire situations and refusing to resort to self-pity. He and Toph live the perverse, parents-free fantasy many children fleetingly harbor, with Eggers sharing his bad habits even as he's forced to assume most of the responsibilities. The writing is never quite as clever or novel as in the virtuoso preface, but Eggers constantly finds ways to make even standard self-analysis interesting. At one point, a bedtime conversation with his younger brother morphs into a psychoanalytic session, with Toph suddenly wresting away the proxy-father-figure position and addressing Eggers with omniscient authority. Later, a casting call-back for The Real World (which actually happened) develops into a long confessional about suburban upbringing. The love of minutia and marginalia Eggers brought to Might makes even the most conventional prose inventive; ironically, this includes the relatively rote chronology of the magazine's creation. While Staggering Genius is admittedly uneven, that's paradoxically part of its unpredictable charm: Eggers would never go about things the standard way, and the book--at times both heartbreaking and genius--ably reflects his idiosyncratic, hyper-casual, pop-culture-saturated worldview. \ — Onion AV Club\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyLiterary self-consciousness and technical invention mix unexpectedly in this engaging memoir by Eggers, editor of the literary magazine McSweeney's and the creator of a satiric 'zine called Might, who subverts the conventions of the memoir by questioning his memory, motivations and interpretations so thoroughly that the form itself becomes comic. Despite the layers of ironic hesitation, the reader soon discerns that the emotions informing the book are raw and, more importantly, authentic. After presenting a self-effacing set of "Rules and Suggestions for the Enjoyment of this Book" ("Actually, you might want to skip much of the middle, namely pages 209-301") and an extended, hilarious set of acknowledgments (which include an itemized account of his gross and net book advance), Eggers describes his parents' horrific deaths from cancer within a few weeks of each other during his senior year of college, and his decision to move with his eight year-old brother, Toph, from the suburbs of Chicago to Berkeley, near where his sister, Beth, lives. In California, he manages to care for Toph, work at various jobs, found Might, and even take a star turn on MTV's The Real World. While his is an amazing story, Eggers, now 29, mainly focuses on the ethics of the memoir and of his behavior--his desire to be loved because he is an orphan and admired for caring for his brother versus his fear that he is attempting to profit from his terrible experiences and that he is only sharing his pain in an attempt to dilute it. Though the book is marred by its ending--an unsuccessful parody of teenage rage against the cruel world--it will still delight admirers of structural experimentation and Gen-Xers alike. Agent, Elyse Cheney, Sanford Greenberger Assoc.; 7-city author tour. (Feb.) Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ KLIATTThis fierce, funny memoir lives up to its tongue-in-cheek title. When Eggers was a senior in college, his parents both died of cancer, only five weeks apart, and he found that he had inherited his eight-year-old brother. He and young Toph (short for Christopher) leave Chicago for Berkley, California, to live near older siblings, but Eggers is the one who serves as chief surrogate parent. The two set up a slovenly bachelor household together, and Eggers attempts to start a career while taking care of his brother, undertaking both endeavors in a rather haphazard but energetic and deeply felt manner. The brothers play Frisbee endlessly and practice sock sliding in their various abodes, eating dishes like "The Mexican-Italian War" (ground beef sautéed in spaghetti sauce, served with tortillas), arriving late to everything but somehow, just barely, keeping it together. The first half of the book, relating the death of Eggers' mother and the move west, is particularly powerful. Wild black humor pops up at the oddest points, however, and Eggers is nothing if not self-conscious, as he keeps pointing out to the reader. Eggers and some friends started a magazine named Might, and much of the second half of the book has to do with keeping this venture afloat. The paperback edition includes a lengthy new appendix, "Mistakes We Knew We Were Making," correcting and annotating parts of the text, and the preface and acknowledgements sections—and even the information on the verso page—are quirky and funny. Eggers is a talented writer, and the story of his patched-together family and his forays into magazine publishing are well worth reading, but strap yourself in for a wild ride. Adultlanguage. KLIATT Codes: SA—Recommended for senior high school students, advanced students, and adults. 2001 (orig. 2000), Random House/Vintage, 544p, 21cm, 00-043832, $14.00. Ages 16 to adult. Reviewer: Paula Rohrlick; May 2001 (Vol. 35 No. 3)\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalIt's a good guess that Jedediah Purdy--the author of For Common Things and righteous agitator against irony--would hate Eggers and his late satirical magazine, Might, right along with this masterly memoir. That is a shame because, despite Eggers's inability to take anything seriously on its surface, this meandering story rests on a foundation of sincerity that is part of Purdy's rallying cry. Amid countless digressions, Eggers relates two tales: his mostly successful, if unconventional attempt at raising his much younger brother following their parents' deaths and his years founding and then witnessing the slow demise of Might. Throughout, Eggers eschews any contrivance. The expected tales of emotional longing, political alienation, and creative struggle by a smart twentysomething are replaced by a stream of hilarious, how-it-happened anecdotes; often inane, how-we-really-talk dialog; and quick jabs at some of our society's bizarre conventions. In the end one is left with a surprisingly moving tale of family bonding and resilience as well as the nagging suspicion that maybe he made the whole thing up. In any case, as compared with the spate of recent reminiscences by earnest youngsters, Eggers delivers a worthwhile story told in perfect pitch to the material. Highly recommended for public and undergraduate libraries. [Previewed in Prepub Alert, LJ 10/15/99.]--Eric Bryant, "Library Journal" Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Daniel HandlerDave Eggers's memoir is a keen mix of self-consciousness and hope, of horror and hysteria and of freshness and wisdom. It's a tonic for anyone who's felt their life becoming a TV Movie of the Week and found themselves torn between laughter, tears, and a nagging urge to change the channel. By eschewing the temptations of cynicism, slackerdom, and navel-gazing, Eggers may end up becomingsomething he richly deserves and probably does not aspire to be: the voice of a generation. \ —The Village Voice Literary Supplement\ \ \ \ \ Michiko KakutaniMr. Eggers demonstrates in this book that he can pretty much write about anything. He can turn a Frisbee game with his brother into an existential meditation on life. He can convey the wild, caffeinated joy he feels after seeing a friend wake up from a coma. And he can turn his efforts to scatter his mother's ashes in Lake Michigan into a story that's both a lyrical tribute to her passing and a crude, slapstick account of his ineptitude as a mourner, lugging about a canister of ashes that reminds him, creepily, of the Ark of the Covenant in the Spielberg movie... A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius may start off sounding like one of those coy, solipsistic exercises that put everything in little ironic quote marks, but it quickly becomes a virtuosic piece of writing, a big, daring, manic-depressive stew of book that noisily announces the debut of a talented -- yes, staggeringly talented new writer.\ \ \ \ \ Sara MosleEggers's book, which goes a surprisingly long way toward delivering on its self-satirizing, hyperbolic title, is a profoundly moving, occasionally angry and often hilarious account...A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius is, finally, a book of finite jest, which is why it succeeds so brilliantly.\ —The New York Times Book Review\ \