A House at the Edge of Tears

In the city of Beirut, five shabby dwellings circle a courtyard with a pomegranate tree weeping blood red fruit. The residents hear screams in the night as a boy is tossed out into the street by his father—a punishment for masturbating in his sleep. A crime not worthy of the punishment: the neighbors gossip and decide that he must have tried to rape his sisters. “Small-boned with long, silky lashes, no one but the devil could camouflage evil so seductively.” The poems he writes are perhaps an...

Search in google:

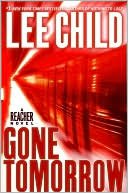

In the city of Beirut, five shabby dwellings circle a courtyard with a pomegranate tree weeping blood red fruit. The residents hear screams in the night as a boy is tossed out into the street by his father—a punishment for masturbating in his sleep. A crime not worthy of the punishment: the neighbors gossip and decide that he must have tried to rape his sisters. “Small-boned with long, silky lashes, no one but the devil could camouflage evil so seductively.” The poems he writes are perhaps an even greater crime to his father, but ultimately a gift to his eldest sister, who narrates their story with a combination of brutal truth and stunning prose. As her brother becomes more and more lost to his family and to himself, we also learn of a Contessa who teaches tango, a family who spends every Sunday in search of buried treasure, and the miracle of a weeping Madonna statue that cries when human tears run dry.In this harrowing and mesmerizing novel, celebrated novelist and poet, Khoury-Ghata, presents the disintegration of a family and a country—both ruled by a fury fueled by fear.Publishers WeeklyKhoury-Ghata, a longtime Lebanese exile living in Paris, is the author of 16 novels and 13 collections of poems in French (including the NBCC finalist for poetry She Says, also translated by Hacker). This self-avowedly autobiographical first-person novel is set in a mostly Christian village outside civil war-era Beirut. It centers on the travails of the narrator's brother, whose masturbation, once discovered, drives the father, a former monk, into rages. (The entire family goes unnamed.) Beating and terrorizing his son viciously, the father ultimately has the boy committed to an insane asylum. To cover up, the father does not quell the rumor that the boy tried to rape one of his sisters. The narrator and her sisters are then sent to a small, devout village in northern Lebanon to live with their aunt and uncle, a coffin maker, and the contact with their parents and brother from then on is intermittent and difficult. The book unfolds in clotted, repetitive lyric bursts, but Khoury-Ghata paints an effectively stylized picture of tyrannical psychosis as it destroys a family, informed by the larger destruction of Lebanese society during the protracted civil war. (Nov.) Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.

A House at the Edge of Tears\ \ By Vénus Khoury-Ghata \ Graywolf Press\ Copyright © 2005 Vénus Khoury-Ghata\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 1-55597-434-1 \ \ \ Chapter One\ The same wind that comes from the sea has run down the same streets for forty years. The rain that used to drench the buildings crosses a field of ruins. At the two extremities of this field: a house where my father conducted a reign of terror and a grave where he found a place not meant for him. He was buried there by chance. War had scrambled the country's geography: the dead were given up to the closest cemetery.\ Two hundred kilometers and more than thirty villages separate him from my mother, born in a village in North Lebanon. Forty years later, I keep asking myself the same question: how did these two come to hate each other so deeply after having once loved?\ I exhume two of my dead and one living-dead: my brother who concentrated within himself all of his father's ambitions and fury; I want to question them, open their mouths sealed in silence, to root out by force the cause of those rages, as brutal and brief as resin-fires.\ In a northern village, the tomb of a Maronite saint has been sweating blood for a century. My father's grave oozes threats from its stony pores. My mother's, modest and moss-covered, seeps tears. My mother had only her tears to defend her son. "God, let him be dead!" I would repeat until I was near fainting when my father was late coming home. I dreamed about being an orphan. Only his death would stop my mother's tears, my brother's cries of terror, and we three girls from trembling.\ On the sixth of December 1950, Father, why did you throw your wife and your three daughters out into the street, keeping your son indoors to tie up on the floor like a mummy? Four faces cramped between the window's bars saw you, puffing and panting in the glimmering light of the lamp placed on the ground as you perfected your work.\ -Don't kill him, my mother begged you.\ -The thought of killing him never crossed my mind. I want to bury him alive.\ Your threats, your son's moans, our sobs have been transformed by time into shame, a shame as penetrating as the rain that soaked the four faces fixed on your slightest movements.\ Forty years later, I throw sentences on the page in great shovelfuls, with a noise of falling earth, as I dig into my shame like a grave. Why did my father play the executioner? Why did our mother weep when she should have spoken up?\ Neither of the protagonists can respond. Prisoners of their death, speech was taken from them at the same time as life, and their son remembers nothing. An eighteen-year confinement in a mental hospital has diluted his memory. His memories stop at the pomegranate tree that hung over the threshold and splattered the landing with bloody juice when its fruit burst open in the sun.\ To each his own tomb: mine is in these pages. Your name, Mother, is black handwriting on a stone covered in snow six months of the, year. I call on, you, taking care to enunciate the syllables, and you come toward me without using your crutches; you stop behind me, read over my shoulder the sentences that tell your story in a language you never mastered.\ You spoke it so badly that your daughter blushed when you spoke up at school parents' meetings.\ Shame at my mother's "Lebanofrench," at my father's rages, which roused our neighbors from their beds and lined them up facing our door. Shame above all at our thwarted love for that man and that woman who are now turning to dust at the two extremities of the country. Shame at displaying my shame on a page for as long as I have been writing books.\ I swallow my shame as I once swallowed the food my mother cooked. Her vegetables were shut in a steamer like our cries, her oversalted salads probably seasoned with her tears.\ When the dinner hour arrived, she would call us from the kitchen window facing the evening that made the nettles in the garden and the lowest branch of the pomegranate tree shiver. Only these have survived the seventeen years of war. In the razed house, someone is crying within the vanished walls. The six protagonists curse and insult one another across the disappeared window bars. The father and the son within, the mother and three daughters outside. I ask the two dead, the living-dead, and the three survivors to pick up their cues, speak their lines where they left them forty years ago. I wait for words and I hear sobs. My mother weeps in the evening, in the morning, in winter and in summer, weeps on my hand as it writes.\ Pitying looks from the neighbors the next morning. Their children avoid us on the way to school and tell their friends about our cries in the night, your martyrdom and your mother's entreaties.\ -Don't kill him, she kept repeating.\ I didn't take part in the other children's games, that day or the days after. I stopped playing at the age of nine. Shame nailed me to the ground. Recess-that was for normal children. I made the excuse that my knees were weak, limped to prove my good faith, still limp out of habit.\ A cemetery's silence, in the evening, at home. Your mother's lips blue, as if she had been eating blackberries; blue, too, the rope marks around your neck. You wear them with pride, like a saint his stigmata. Suddenly, a tango melody escaping from a neighboring window etches a blindly blissful smile on your swollen lips. You get up like a bird ready to take flight. You move away from the spot where you knew humiliation and fear. You are deaf to your little sister's sobbing. Mina weeps for no reason. The violin saws at her heart and last night has left her with delicate nerves. The phonograph of Madame Alma, director of the Universal Tango Institute, is your only way to leave these walls soaked through with your sweat and your blood. The music stops, you are among us again, and immerse yourself in your homework. You work in semidarkness; the second lamp that lit the living room was broken yesterday when your father tied you up on the ground.\ Seated on the doorstep, my mother scrutinized the darkness, searching for a silhouette. She made a place for me beside her and explained that I ought not to hold a grudge against my father.\ -He is clumsy. He doesn't know how to express his affection. It's because of grave events that go back to his childhood in a country beyond the border.\ Her hand swept the north behind her shoulder.\ -No one, she added, ever knew where they came from, the woman and the two boys who got out of a cart on the square of a southern village. Had they chosen the place for the shade of its plane trees or for the gaping doorway of the church? That woman, was she a widow, or was she fleeing from a too-brutal husband, an assassin perhaps? Bent over the washtub of the monastery where she had taken refuge, she still had the bearing of a queen. Her meager wages permitted her to pay for her elder son's schooling; she ceded the younger to the monks. He would take the habit. Such a secretive woman: she never referred to her daughter kept behind by the irascible father, a daughter whom she would find again twenty years later, dressed in the traditional garments of peasant women from the plains that supply Syria with its wheat, the dress of seasonal workers traveling with the harvests from all over the Middle East.\ My mother brought the shame forward from generation to generation, right up to the doorstep where she waited.\ -And the young monk?\ My voice startled her. She had forgotten my presence, so preoccupied with reconstructing the family of the man she had married.\ -The young monk broke his vows after his return from Rome. In the hospital with appendicitis, he met me. He married his nurse. The doctorate in theology wasn't good for much. He had to find other prospects. He became an interpreter under the French mandate, the army absorbed him after the French left. A mystic in a world of brutes. He never recovered from it. He could have become a bishop or even a cardinal had it not been for that accursed appendicitis, which turned him away from his vows. An orphan of France. He threatened every morning to blow his brains out. An invisible hand held him back at the last moment. He didn't have the right to attempt suicide; he was the father of five children, four girls and a boy.\ -Three girls, I felt obliged to remind her.\ -Four, she insisted. The eldest died at the age of eight months. She broke her father's heart and made him doubt God. He wrote a long poem for her funeral with lines of the same length and the same width. You ought to have seen him gesticulate above the little coffin. The few neighbors who had accompanied us to the cemetery could barely keep from laughing. His voice trembled in the wind. A glacial day. The gravedigger worked like a dog digging into the frozen ground. His spade in the air, he waited for the end of the poem to fill up the hole. That man is jinxed, the curse will follow him from life to life. He took advantage of the poor monks, ate the monastery's bread with impunity. When he had finished his theological studies, he traded his cassock for a three-piece suit. The little one paid for his sins. Dead.\ -You've never talked about her ...\ -What would be the use!\ -Do you have a photo of our sister?\ -A photo, a photo! That's easy to say. You needed an occasion: baptism, first communion. The little one didn't wait. Always sick, as if she were in a hurry to leave. I'll say it again: she had to pay for him.\ -What was her name?\ -How do you think I can remember it after all these years! Victoire, if my memory is right, or maybe Victorine.\ A man's footsteps, recognizable among all others, made her jump. She got up, tied her apron, and disappeared into the kitchen. My father emerged from the darkness. His army boots made the gravel creak on the footpath.\ "A man should refuse to live when he has planted his child under a cypress," my father would repeat, and his mouth stayed shut after prouncing the name of that funereal tree.\ God had taken from him the child he loved and left the one he loathed. From where did he get this son? This unruly boy who resembles no one in the family? He is small-boned with long, silky lashes: no one but the devil could camouflage evil so seductively. Pristine features for a soiled soul: he reads books that have banished God from their pages, listens to music as black as the continent that gave it birth. A music come from far away. My father had a hard time accustoming himself to this son's presence under his roof. A question escaped from him from time to time, murmured like an insult: "Why did he choose my home rather than the Vinikofs' more spacious one? His perversity would be well adapted to their madness. His lack of austerity would go well with their appetites."\ Our Sundays were dreary indeed compared with those of the Vinikofs, who lived in a well-kept building on the other side of the street. The whole family would crowd into an old Packard to go and dig for buried treasure a hundred kilometers outside Beirut. The Armenian magus who had revealed its existence to the engineer Vinikof had not been skimpy with details. One had to turn off after a bridge, follow the railroad tracks, drive through farmlands to the base of a hill, then stop in front of a tuft of broom. The bridge, the hill, and all the rest could be found on the map; all the map lacked were the railroad tracks. The Vinikofs weren't going to be dissuaded by such a small detail. They decided that the Armenian had seen the site with his third eye, and they turned south. Two adults and four children took off every Sunday under our dazzled gazes. The head of the expedition, at the wheel, wore a compass around his neck.\ We would wait for their return as late as it might be, ready to spend the night on the sidewalk. The headlights of the car as it reappeared made us blink. We bombarded them with questions though they were staggering with fatigue.\ -And the treasure?\ They showed us their hands covered with blisters, their legs scratched to ribbons by thorns.\ -But did you find it, the treasure?\ -That will be for next Sunday.\ And that was their answer, for five years. At the moment when the earth was opening beneath their pickaxes, they would hear the sound of axes like their own striking the ground from the other side of the hill. Blows that stopped when the Vinikofs stopped digging and began again when they went back to work.\ -Do you mean that other people are ...\ They would shake their heads in both directions: a yes bedecked with a no.\ -If you want to call devils people, they would say.\ The wise man had warned their father.\ -Your task, engineer, will not be an easy one. You will have to struggle. Demons will track you down. They will follow your every step, and will dig on their own side. I advise you to throw them off the track, to pretend you're giving up, to leave, since you'll have to return when they have their backs turned, otherwise their axe blows will always answer yours, five seconds later, not one more.\ It was astounding. Mina, who dared to suggest echoes, was asked to keep her opinions to herself. One doesn't contradict a magus. As to echoes, the engineer Vinikof had certainly thought of that.\ Emotion enhancing their appetites, the Vinikof family rushed into the kitchen, where each one prepared his or her own specialty. Fat Roro's platter of a dozen fried eggs resembled a virgin planet scattered with craters. Skinny Youri, who spent his time masturbating, spied on by his two sisters, ate only asparagus and mayonnaise. The steaming casserole placed by the mother in the middle of the table was as deep as the baptismal font in the parish church. What steamed within smelled of sumac, cumin, saffron, and lamb. The ceiling sweated copiously while the six members of the family ate. The adults did so with appetite, the twin girls who were in my class picked at their food. All these savory dishes only filled them with disgust. They preferred our own mother's bland and tasteless cooking. A hospital diet.\ Macha and Yara had trouble getting up in the morning to go to school. I would call them by rapping three times on the window, then wait for them with my nose pressed to the pane, sometimes for more than an hour. Their disorder fascinated me. It contrasted sharply with the order that reigned in our house. The nightshirts rolled up at the foot of their beds smelled of healthy sleep. The mufflers hung from the lamp were flags at half-mast. Macha and Yara crawled under their beds to retrieve their shoes and fought like dogs for the same sock, which ended up as two half-socks, one piece gripped in each one's hand. Well-behaved Roro slept fully dressed, and Youri, who had banished socks from his life, exhibited ankles as skinny as a rooster's without embarrassment. A temporary emaciation, according to his sisters. Youri would fill out again as soon as he lost the unfortunate habit of masturbating.\ Youri's masturbation-a subject for humor for the Vinikofs. Your nocturnal ejaculations, Victor, are the subject of drama in our family. Your father snatches you from sleep and then throws you outdoors for the rest of the night. You are the shame of the family. You have soiled the sheets washed by your saintly mother. The door, violently slammed, wakes the neighbors. Lined up in front of the window, they plead with your father for clemency and console your mother with inadequate words. They are all there. The show is free. Four children and two adults act out scandals to distract them. Our landlady, Madame Rose, is followed by the four racetrack brothers and their sister, Mademoiselle Renée. Madame Alma, called the Contessa, argues with Georges Vinikof in a low voice. Madame Latifa, the Muslim, stands behind them. Her religion forbids her to show herself unveiled. They sympathize with my mother while agreeing with my father in principle. What will become of us if fathers no longer have the right to discipline their children? Only Monsieur Alphonse isn't there. Our drama doesn't interest him.\ The rumor, embellished with new details, travels around the neighborhood. Fabrications become evidence. You were about to rape one of your sisters, never mind which one, when your father intervened. You don't throw your son out into the street for a commonplace loss of semen. You inspire mistrust. Children run away at the sight of you and their mothers interrupt their conversations as soon as you appear. Some of them cross themselves. The retirees who play backgammon in front of their doorsteps forget to throw the dice.\ -Such a good-looking boy. What a pity that he's a pervert.\ All you had to do was slow down to catch the rest of the sentence.\ -He's paying for the sins of his father: a defrocked monk who made use of the poor monks' generosity to go to school and to see the world. So much for the monastery, he married his nurse.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from A House at the Edge of Tears by Vénus Khoury-Ghata Copyright © 2005 by Vénus Khoury-Ghata. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ Publishers WeeklyKhoury-Ghata, a longtime Lebanese exile living in Paris, is the author of 16 novels and 13 collections of poems in French (including the NBCC finalist for poetry She Says, also translated by Hacker). This self-avowedly autobiographical first-person novel is set in a mostly Christian village outside civil war-era Beirut. It centers on the travails of the narrator's brother, whose masturbation, once discovered, drives the father, a former monk, into rages. (The entire family goes unnamed.) Beating and terrorizing his son viciously, the father ultimately has the boy committed to an insane asylum. To cover up, the father does not quell the rumor that the boy tried to rape one of his sisters. The narrator and her sisters are then sent to a small, devout village in northern Lebanon to live with their aunt and uncle, a coffin maker, and the contact with their parents and brother from then on is intermittent and difficult. The book unfolds in clotted, repetitive lyric bursts, but Khoury-Ghata paints an effectively stylized picture of tyrannical psychosis as it destroys a family, informed by the larger destruction of Lebanese society during the protracted civil war. (Nov.) Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalIn this small, poetic novel resides the fury, despair, shame, and love of a book ten times its size. Khoury-Ghata (She Says), an award-winning poet and novelist, writes about her native Lebanon in this semiautobiographical story of a family ruled by an abusive father and a country on the cusp of civil war. In an eccentric neighborhood of five houses lives a tortured man whose grief at the loss of a daughter is transformed into rage at the creative son he cannot understand. His wife and three remaining daughters witness the physical and mental abuse of the young boy, who eventually abandons his poetry and descends into madness. Interspersed with the family's sufferings are the stories of the neighbors: the Vinikofs who hunt for buried treasure on the weekends, the Contessa who teaches tango lessons, and the landlady at whose house a vision of a weeping Holy Virgin appears. From her own tortured memories, Khoury-Ghata has made a painfully beautiful and, at times, amusing creation that redeems and honors those who lived through horrible events. Sensitively translated by Hacker, an award-winning poet in her own right, this is recommended for public and academic libraries.-Joy Humphrey, Pepperdine Law Lib., Malibu, CA Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAt home with a violent father in war-ravaged Lebanon. Lebanese poet and novelist Khoury-Ghata, whose She Says (2003) was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry, addresses a formative personal episode in this semi-autobiographical novel. With both her parents now dead, the author says she is free to evoke "a reign of terror," the destruction of her poet brother's mind by their father's tyrannical treatment. The father himself was a haunted man, an ex-priest who broke his vows. Suicidal, believing himself cursed by the monastery, he was a figure of rage whose loathing for his son was as irrational as it was violent. The boy was expelled from the house for having nocturnal emissions and banished to a monastery. Escaping after three months, he took up with a fringe crowd, then became the lover of an elderly Englishwoman before fleeing to Paris, where he wrote poetry and became a drug addict. The father saw poetry as "an accursed genre that spread madness" and, upon the son's return, had him incarcerated in an asylum. There, drugs, shock treatment and years of institutionalization slowly destroyed him. This narrative is spliced between stories of the family's neighbors, who shared a group of five houses. There are magical-realist episodes-a weeping image of the Holy Virgin, the reappearance of a dead dog-and darker tales, like the death of a young mother in childbirth after her husband refuses medical intervention. The Lebanese civil war resulted in the brother's release from the asylum. He returned to his mother's love and to his father's unyielding hostility. Khoury-Ghata's postscript reveals that she and her sisters have taken up writing in honor of the brother who"had all his links with writing cut."A choppy mixture of style and content that touches some emotional chords.\ \