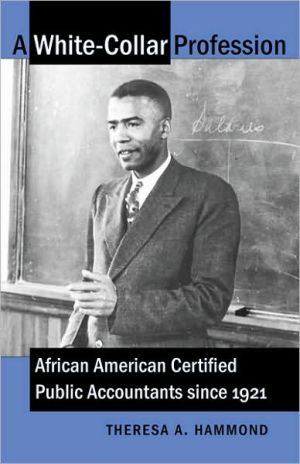

A White-Collar Profession : African American Certified Public Accountants since 1921

"Among the major professions, certified public accountancy has the most severe underrepresentation of African Americans: less than 1 percent of CPAs are black. Theresa Hammond explores the history behind this statistic and chronicles the courage and determination of African Americans who sought to enter the field. In the process, she expands our understanding of the links between race, education, and economics." Drawing on interviews with pioneering black CPAs, among other sources, Hammond...

Search in google:

Among the major professions, certified public accountancy has the most severe underrepresentation of African Americans: less than one percent of CPAs are black. Theresa Hammond explores the history behind this statistic and chronicles the courage and determination of African Americans who sought to enter the field. In the process, she expands our understanding of the links between race, education, and economics. Drawing on interviews with pioneering black CPAs, among other sources, Hammond sets the stories of black CPAs against the backdrop of the rise of accountancy as a profession, the particular challenges that African Americans trying to enter the field faced, and the strategies that enabled some blacks to become CPAs. Prior to the 1960s, few white-owned accounting firms employed African Americans. Only through nationwide networks established by the first black CPAs did more African Americans gain the requisite professional experience. The civil rights era saw some progress in integrating the field, and black colleges responded by expanding their programs in business and accounting. In the 1980s, however, the backlash against affirmative action heralded the decline of African American participation in accountancy and paved the way for the astonishing lack of diversity that characterizes the field today. Lee A. DanielsNot only a brilliant and poignant history of one significant profession; it speaks volumes about the larger struggle African Americans have waged since the early 1900s to secure their place in the American mainstream.

A White-Collar Profession\ African American Certified Public Accountants since 1921\ \ \ By Theresa A. Hammond\ \ University of North Carolina Press\ Copyright © 2002 The University of North Carolina Press.\ All rights reserved.\ ISBN: 0807827088\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ The Whitest Profession\ When Theodora Fonteneau Rutherford graduated summa cum laude from Howard University in 1923, she dreamed of becoming a certified public accountant (CPA). Her favorite accounting professor had encouraged the talented nineteen-year-old to strive for the pinnacle of the accounting profession, providing her with questions from prior CPA examinations to help her prepare. She earned a scholarship to Columbia University's graduate school of business, and she hoped that New York would provide opportunities that had been unavailable in the southern states in which she had been raised. Although she was bright, well-educated, hardworking, and determined, Rutherford was prevented from achieving her goal for the next thirty-seven years. When she finally became a CPA in 1960, she was one of only a few dozen African American CPAs in the entire country.\ This book chronicles the stories of several of the pioneering African American men and women who managed to surmount the obstacles to becoming a CPA and whose history has been all but ignored. Their experiences paralleled those of African Americans who pursued other professions in the twentieth century. Segregated educational institutions posed challenges to acquiring the requisite expertise; white employers, whether hospitals, law firms, or CPA firms, were reluctant to hire African Americans; clientele were limited to the economically disadvantaged African American community; and professional societies held meetings in segregated hotels or excluded African Americans outright. The stories of these individuals provide a new and important perspective on the history of the professions, the perspective of those who fought to join elite occupations in which they were not welcome.\ In the 1920s, African Americans were excluded from most professions. Exclusion—whether based on educational achievement or on race—is a traditional method by which professions enhance their prestige. From their professional beginnings, both law and medicine found that limiting their ranks to the most powerful group in society—wealthy white males—reinforced their own power. CPAs adopted this strategy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, emulating the exclusivity of the more established professions.[1]\ The dearth of African Americans among CPAs is not only a result of exclusion from well-paying professional positions but also the consequence of African Americans' exclusion from the financial sector. CPAs share the defining elements of other professions: a specified area of expertise, a government-granted monopoly over this expertise, and strict rules of entry and conduct. But unlike the quintessential professions of law and medicine, the work of a CPA is completely dependent upon the business activities that drive the American economy. This unique position is one cause of CPAs' status as the least diverse of the major professions.\ \ \ Differences in the development of the professions help explain the variations in underrepresentation.[2] African American doctors and lawyers were denied participation in majority-white institutions for most of the twentieth century, but they were leaders in meeting the medical and legal needs of the African American community. In contrast, centuries of restricted economic opportunities resulted in few African American-owned businesses large enough to require the services of a CPA. Consequently, until the 1960s, only under exceptional circumstances could African American CPAs earn a livelihood within the black community. This difference also meant that while African American medical and law schools have a long history, black colleges rarely offered programs in accountancy.\ \ \ The History of the CPA Profession and the Development of the Experience Requirement\ Barriers to the professions also differed at the entry level. Entrance to the medical and legal professions primarily depended on obtaining the appropriate education and passing state-supervised examinations. Becoming a CPA not only required passing the certified public accountancy examination but also serving an apprenticeship, called an experience requirement, by working for a licensed CPA. For most of the twentieth century, virtually no whites would hire and train an African American to become a CPA, justifying this by claiming that clients would not tolerate an African American's involvement in their financial affairs. The experience requirement constituted an extremely effective barrier; by 1965 there were only one hundred African American CPAs—one in one thousand CPAs.\ Certified public accountancy developed in the United States later than most professions. The first laws creating CPAs were passed in New York in 1896. Accountants and bookkeepers had existed in the United States since the country's inception, but public accounting did not begin to expand until the early twentieth century. Accountants and bookkeepers keep track of a company's or an individual's records, whereas CPAs are authorized to provide audits—external reviews of an organization's accounting records—certifying that these records comply with accounting regulations. This authority made CPAs the most elite members of the accounting field. While the term "accountants" encompasses a variety of roles, including working within corporations, the government, and small businesses, CPA firms operate like law firms—CPAs work for themselves or in partnerships and provide services to clients.\ Public accounting rose in importance along with industrialization and the concentration of capital. As companies became larger, they sold stock to raise capital rather than being controlled by small groups of manager-owners. The stock market created "absentee owners," people who held stock in a corporation but were not involved in its management. These stockholders required assurance that companies were meeting expectations, and the public accountants' audits attested to the reliability of the company's income statement and balance sheet. The goal of these audits was to strengthen investor confidence, enabling companies to raise the capital needed for the mammoth corporations that emerged in the decades after the Civil War.\ Variation among public accountants and questions regarding their reliability led to efforts to organize the profession in order to enhance its credibility. The primary model for these efforts was the British system of chartered accountancy. In England, prospective chartered accountants were required to serve a five-year apprenticeship in order to earn the authority to attest to corporate financial statements. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many English chartered accountants came to the United States to take advantage of the emerging need for their services. Together with their United States counterparts in public accounting, they sought to forge a professional credentialing process.\ Disagreements immediately arose over whether the British model should be emulated. Several United States-born public accountants objected to the apprenticeship model, which restricted professional entry to the wealthy few who could afford to pay for the apprenticeship. Those who preferred the British model, however, stressed the prestige associated with such a plan. By confining entry to the upper and middle classes, the profession would enhance its legitimacy and promote a status comparable to those professions already established in the United States, especially medicine and law. Early debates about the profession's direction pitted eastern Anglo-Saxon Protestant elites, who favored restrictive entry, against midwestern, often Catholic, first- and second-generation Americans from continental Europe and Ireland. The latter group favored educational and testing requirements, which they perceived as more democratic and more consistent with American ideals.[3] Not unexpectedly, given their exclusion from mainstream society, African Americans were completely ignored in the debate.\ Because of the intense regional and social differences, efforts to create national criteria failed. Instead, each state developed its own laws governing the profession. Most states, including New York, compromised, requiring both the passage of an examination and an apprenticeship with a CPA. This apprenticeship, which differed from the British system in that the employee was paid for his or her work, varied by state: some required only one year and others required as many as three.[4]\ Even without the complete adoption of the British five-year apprenticeship system, the experience requirement had an exclusionary effect because it created a nearly impenetrable barrier to African Americans who desired to become CPAs. By the end of the century, there were 400,000 CPAs in the United States, less than 1 percent of whom were African American.\ Although the profession garners relatively little media attention, it does wield substantial power over the nation's most consequential financial transactions. In addition to involvement in tax regulations and business management, CPAs have the exclusive authority to audit the income statements of all publicly traded corporations. Today a handful of firms dominate the industry: PricewaterhouseCoopers, Arthur Andersen, KPMG, Deloitte & Touche, and Ernst & Young. These firms audit over 95 percent of the Fortune 500, earning 1998 revenues in excess of $40 billion.[5] But none of these firms employed African Americans until the 1960s.\ \ \ Those Who Made It\ African Americans who managed to become CPAs prior to the 1960s had exceptional characteristics. All of them personified talent, persistence, and resilience. These pioneers were remarkably accomplished students with outstanding educational backgrounds, exceeding those of many of their white counterparts. Some moved hundreds of miles to achieve their educational goals, to obtain employment with an African American, or simply to find a state that allowed African Americans to take the CPA examination. Some spent years seeking employment in the field. A few of the earliest CPAs came from the most elite African American families in the nation. A handful appeared to be white. All these characteristics reduced the difficulties they faced; nevertheless, intense challenges remained.\ Because finding employment with a white-owned CPA firm was nearly impossible, African Americans helped each other. Arthur J. Wilson became a CPA in Chicago in 1923, before the State of Illinois passed legislation requiring an apprenticeship with a CPA. Wilson then provided experience to others, so that by 1945 half of all the African American CPAs in the country worked in Chicago. Chicago CPAs provided services to some of the largest black-owned businesses in the country. Men and women in other African American business centers—Atlanta, Detroit, and New York—similarly blazed a trail that others could follow. Those who wished to become CPAs often had no alternative but to move to meet the experience requirement by working for one of these pioneers.\ Moving typically meant moving north. Business education was severely restricted in the South, and barriers to employment were insurmountable. Many African Americans, excluded from the business programs of their state universities prior to the civil rights movement, went to northern schools in order to major in accounting. Until the 1960s, there was only one school in the South that offered substantial business education to African Americans, Atlanta University. Interviews with dozens of African American CPAs from all regions of the country revealed that many of them received early encouragement from one influential man, Jesse B. Blayton, Sr., an accounting professor at Atlanta University who became Georgia's first African American CPA in 1928.\ Moving north did not solve every problem, however. All those who earned their CPAs prior to the 1960s exemplified perseverance. Some applied for dozens of jobs before finding a crack in the system, even in ostensibly liberal cities such as New York and Los Angeles. Many reluctantly turned to teaching, a field open to African Americans as long as schools were segregated.\ Obtaining a CPA license did not mark the end of the struggle. African American CPAs usually had to eke out a living within the black business community, since it was almost impossible to attract white clients. Many had to retain full-time jobs while conducting their professional practice at night and on weekends—despite the fact that their white contemporaries found certified public accountancy to be a lucrative profession. In addition, for decades African American CPAs were excluded from many CPA professional associations and meetings and thus were denied opportunities to make business contacts and remain current with professional developments. For example, Dr. Lincoln Harrison, who earned his CPA in Louisiana in 1946, was not admitted to the Louisiana Society of Certified Public Accountants until 1970.\ The Civil Rights Act of 1964, which forbade employment discrimination on the basis of race, brought an end to the most intransigent barriers to African Americans' becoming CPAs. In the late 1960s, the major CPA firms began recruiting at black colleges and the American Institute of CPAs initiated programs to encourage African Americans to major in accounting. President Lyndon B. Johnson's War on Poverty provided much-needed funds to urban community organizations, which in turn required the services of CPAs. This finally provided sufficient clientele in the African American community to enable many African American CPAs to earn a living within the field. The expansion of civil rights organizations also led to more demand for black CPAs. When the State of Alabama charged Martin Luther King Jr. with tax evasion, he hired Atlanta CPA Jesse Blayton to help clear him.\ Following the civil rights movement, there was a surge in African American participation in the profession. In 1961, for the first time, a major firm hired an African American accounting graduate. During the mid-1960s a handful more were hired. The biggest change came at the end of the decade, when the American Institute of CPAs called for efforts to integrate the profession. For a short period, the major public accounting firms, which had previously refused to hire African Americans, began actively recruiting at black colleges. In 1968, the major firms in New York employed only eighteen African American accounting professionals. By 1970, there were 700 African Americans in the same offices.\ That surge sputtered in the 1980s. Proactive efforts to expand opportunity shrank as affirmative action plans came under siege from the Reagan administration. The representation of African American professionals in major CPA firms declined by over 25 percent. In the century's last decade, participation leveled off as some firms recognized that the slide was disadvantageous to preserving their clients, who themselves were becoming increasingly diverse. As in earlier periods, African American CPAs played the key role in ensuring that opportunity did not completely disappear. Through the expansion of programs at historically black colleges, activism on the part of African American CPAs, and the growing National Association of Black Accountants, African American leadership persevered as the profession entered a new century. \ \ \ Excerpted from A White-Collar Profession by Theresa A. Hammond. Copyright © 2002 by The University of North Carolina Press. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. \ \ \ \

Acknowledgments1The Whitest Profession12The Firsters83The Black Metropolis284Postwar CPAs: Overcoming Barriers455The 1960s: Decade of Change676Accounting Programs at Black Colleges957The Momentum Is Lost1148Entering a New Century136AppThe First 100 African American CPAs147Notes151Bibliography189Index203

\ From the Publisher[Hammond's] research will help readers realize that a more diverse profession is in both their ethical and their economic interests, resulting—we can hope—in a happier tale about the twenty-first century. (Robert K. Elliott, past chairman of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants)\ A thoroughly engaging and well-researched chronicling of the African American experience in one of the nation's most important and prominent professions. Hammond has broken new ground in the study of race and business. (David A. Thomas, author of Breaking Through: The Making of Minority Executives in Corporate America)\ Not only a brilliant and poignant history of one significant profession; it speaks volumes about the larger struggle African Americans have waged since the early 1900s to secure their place in the American mainstream. (Lee A. Daniels, editor of The State of Black America)\ \ \