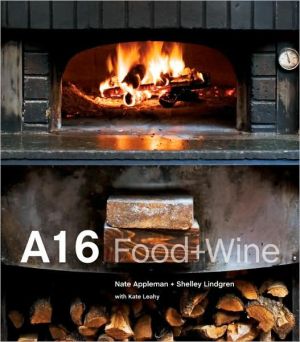

A16: Food + Wine

A cookbook and wine guide celebrating the traditions of southern Italy, from the country's top southern Italian restaurant, in San Francisco.\ At San Francisco's acclaimed A16 restaurant (named for the highway that cuts across southern Italy), diners pack the house for chef Nate Appleman's house-cured salumi, textbook Naples-style pizzas, and gutsy slow-cooked meat dishes. Wine director Shelley Lindgren is renowned in the business for her expeditionary commitment to handcrafted southern...

Search in google:

A cookbook and wine guide celebrating the traditions of southern Italy, from the country's top southern Italian restaurant, in San Francisco.At San Francisco's acclaimed A16 restaurant (named for the highway that cuts across southern Italy), diners pack the house for chef Nate Appleman's house-cured salumi, textbook Naples-style pizzas, and gutsy slow-cooked meat dishes. Wine director Shelley Lindgren is renowned in the business for her expeditionary commitment to handcrafted southern Italian wines. In A16: FOOD + WINE, Appleman and Lindgren share the source of their inspiration—the bold flavors of Campania. From chile-spiked seafood stews and savory roasts to delicate antipasti and vegetable sides, the recipes are beguilingly rustic and approachable. Lindgren's vivid profiles of the key grapes and producers of southern Italy provide vital context for appreciating and pairing the wines. Stunning photography captures the wood-fired ambiance of the restaurant and the Campania countryside it celebrates. Publishers Weekly One of San Franciscoa's most popular new restaurants, A16 is devoted to southern Italya's rustic cuisine and robust wines. This book, by its executive chef and wine director, begins by exploring eight grape-growing areas in the south, from the regiona's heart in Campania to mountainous Abruzzo and the isolated island of Sardinia in the Mediterranean. With a dizzying number of wines produced in each area, the focus is wisely kept on the grapes themselves, with eloquent essays on the history and qualities of both classic and less familiar red and white varietals, and food pairing tips as well as recommendations of wine producers. The second half presents some of those foods-"peasant cooking" like pasta with chunky, chili-spiked sauce, a rabbit mixed grill and, of course, Neapolitan pizza, with A16a's Bay Area location showing in occasional ingredient twists like the tangerines in an arugula salad and the zesty punch of preserved Meyer lemon in a grilled shrimp dish. Executive chef Applemana's expertise is reflected in a chapter on "the pig," including recipes for making pancetta and sausages, which are rather advanced for casual home cooks but, like the rest of the book, make fascinating reading for lovers of Italian food and wine. (Sept.)Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

A16 Food+Wine\ \ \ By Nate Appleman Shelley Lindgren Kate Leahy \ TEN SPEED PRESS \ Copyright © 2008 \ D.O.C. Restaurant Group, LLC\ All right reserved.\ \ ISBN: 978-1-58008-907-4 \ \ \ \ \ Chapter One PART ONE\ A16 WINE\ A glass of crisp Bombino Bianco paired with a piece of creamy Burrata. Ruby red Nero d'Avola served with a blistered pizza margherita. Juicy Casavecchia beside a plate of grilled rabbit. Serving these southern Italian wines, and many others, with our regional menu is our way of paying homage to the corner of the world that inspires us. Through the weekly exercise of tasting, exploring, and talking with producers and importers, we are constantly exposed to the breadth and depth of wines that southern Italy offers. Some of them contain nearly extinct grape varieties, while others are blends of indigenous and international grapes made by winemakers who flout tradition as if it were the speed limit on a southern Italian motorway. We don't just offer these wines to our guests for the sake of discovery, though. The wines simply belong with the gutsy country cooking of Campania.\ When we began planning to open a restaurant that serves Neapolitan-style pizzas, I sampled a few Campanian wines out of curiosity. With little knowledge of the region's offerings, I was intrigued by my first tastings. My learning curve was steep but invigorating. Coming across wines made with honey-hued Pallagrello Bianco, a grape that less than twenty years ago grew in only one vineyard, inspired me to dig deeper into the region's viticultural history. But it was the expression of Aglianico emanating from a glass of Antonio Caggiano's Taurasi that gave me the confidence to focus the wine list on southern Italian wines.\ Once A16 opened, our enthused staff began urging Sauvignon Blanc drinkers to take a chance on Greco di Tufo from Campania and professed Pinot Noir fans to try Cirò from Calabria. While at first we had to endure the inevitable requests for Chianti, our decision to promote southern Italian wines was timely. Regions such as Abruzzo, Puglia, and Sicily were just beginning to show what they are capable of producing. Meanwhile, forgotten regions such as Basilicata, Calabria, Sardinia, and Molise had been rediscovered. Southern Italian wine clearly deserved attention, and we soon found we had a dining room full of curious customers interested in expanding their wine horizons.\ THE MEZZOGIORNO\ Even though interest in the wines of southern Italy continues to grow, I am still amazed when guests ask for a glass of Falanghina without blinking. Recognition has come quickly, a testament to the accessibility of the wines and the many charms of southern Italy. Often called the Mezzogiorno for the way the sun hovers over the country's southern horizon at midday, Italy's south-Abruzzo and Molise east of Rome, Campania on the shin of the peninsula's boot, Calabria on its toe, Puglia at its heel, Basilicata in between, and Sardinia and Sicily past its shores-comprises rocky cliffs overlooking the azure Tyrrhenian, Ionian, and Adriatic seas; dormant and active volcanoes; arid plateaus; thick pine forests; and fertile valleys. It is not unusual in either Calabria or Sicily for an hour's drive to take you from a lush mountain forest to a dry Mediterranean coast where cacti thrive, or to see water buffalo native to India grazing in Campania's fertile valleys. It is a land of natural drama and splendor, a place where the Greeks worked and the Romans played. It's also a land full of grape biodiversity, where volcanic soil preserved some ancient varieties from the deadly vine pest phylloxera.\ For all this natural wonder and formidable history, there are plenty of reasons why modern wine drinkers have long ignored Italy's south. In fact, it wasn't too long ago that most Italian wine had the reputation for being worth less than the bottle it came in, a criticism that was especially true of southern wines. The southern Italian countryside, already poor throughout much of Europe's history, was not helped by the wars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which shook apart the region's tenuous economy. A tourist visiting Campania in 1950 en route to the region's coastal resort towns Amalfi and Sorrento would have driven by peasants walking barefoot through crowded streets with baskets on their heads. In an effort to stimulate the rural economy, numerous government-backed subsidies supported prolific vineyard plantings. While all of Italy ended up swimming in indistinguishable surplus wine as a result, the effect was particularly enduring in the south, where a system of cooperatives relieved small vintners of selling modest lots of grapes by collecting them and selling them with other vintners, thus encouraging high yields for bulk wine production.\ Yet modern history overshadows the region's ancient viticultural practices, varied but favorable growing climates, and abundance of indigenous grape varieties. When the Greeks arrived on the Italian peninsula four thousand years ago, they named it Oenotria, "land of wine," in reference to southern Italy's shores, which were already thick with grapevines. The Romans followed the Greeks' example and also prized southern Italy's wines, particularly Campania's sweet, amber Falernum made with Falanghina grapes harvested on the slopes of Mount Massico, believed to have been blessed by Bacchus himself.\ While grapes were growing across southern Italy before the Greeks arrived, the gnarled, twisted, low-lying vines wouldn't be recognizable as vineyards to the modern eye. It wasn't until the Greeks introduced the albarello method, in which vines are trained up posts to resemble short trees, that the plants were tamed into neat rows. Ancient vintners also practiced other trellising methods to control vine vigor. One of the most memorable vineyards I have ever seen is in the northern Campanian town of Aversa, where Asprinio vines climb up tall poplar trees, and vineyard workers use ladders to harvest the grapes used in the Aversa DOC. This ancient method of trellising vines in trees is also used on a smaller scale. Eating lunch at a small trattoria near Avellino, I sampled a simple table wine made on the property. Outside, the trattoria's vines curled up tree branches, freeing up a patch of land for the proprietor's vegetable garden.\ Even during the dark years of the modern era, a few producers in each region of the south remained focused on quality winemaking. Families such as Paternoster in Basilicata, Illuminati in Abruzzo, and Mastroberardino in Campania made wines worthy of the Mezzogiorno's noble traditions. The perseverance of these producers was finally rewarded in the 1990s, when interest in making wines of character and class began to grow.\ Today, southern Italy is well on its way to reclaiming its rich winemaking heritage. Encouraged by regulations put forth by the European Union and the Italian government discouraging bulk wine production, clever Italian wine mavericks and entrepreneurs began to realize the undertapped potential for making wines of place in one of the world's oldest wine regions. Modern technologies, such as temperature-controlled fermentation tanks, paired with an allegiance to traditional grapes, have reinvigorated the area, making it one of the world's most intriguing winegrowing regions. At the restaurant, our chalkboard proudly lists some of my favorites, such as Campania's versatile Fiano, Calabria's easygoing Gaglioppo, Abruzzo's crowd-pleasing Montepulciano, Sardinia's elegant Vermentino, and the compelling Nerello Mascalese wines made near Sicily's Mount Etna. I'm also keeping an eye on Puglia, where producers whisper that the fickle Nero di Troia grape might bring forth southern Italy's next cult wine.\ INTERPRETING THE GRAPES\ Most wine drinkers in America think about wine in terms of the grape used to make it, rather than the place where it was made. Because of this tendency-and also because when I began learning about southern Italian wines, I found the stories of how the grape varieties persevered through time stuck with me more than the place designations did-I have adopted the grape-forward approach to organizing the wines in this book. It also happens that some of southern Italy's best wines are made with only one grape variety, cento per cento.\ Each of the regional wine sections that follow (with the exception of Molise and Basilicata) features a catalog of the area's grapes. I have ordered the grapes from can't-miss varieties-The Classics-to intriguing grapes on the horizon, grouped under A Closer Look. While not every shop will carry southern Italian wines, chances are that if they do, they will be wines made with grapes from the former category. But with the wine regions of southern Italy evolving so quickly, some of the lesser-known grapes could well become classics in a handful of years.\ THE LAWS\ The grape-forward approach doesn't entirely align with Italy's unwieldy wine classification system, so it helps to have a basic understanding of the country's viticultural laws. It is also important to keep in mind that such regulations have a way of bending without breaking.\ Inspired by the French Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée system founded in the 1930s, the Italian classification was instituted in 1963 as a way to control the quality, protect the distinctive regional character, and raise the stature of the country's wines. There are four levels of classified wines in Italy, and even if you aren't looking for the classifications on a bottle, the appropriate band circles the neck, a mark of quality as designated by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. The highest level, Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG), has the strictest production requirements, while the lowest, Vino da Tavola, has the most relaxed. Following DOCG is Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC), which has similar regulations without the same amount of prestige (there are many more DOCs than DOCGs). Indicazione Geografica Tipica (IGT), which refers to wines produced in specific regional areas, follows DOC. It is generally a zone much larger than a DOC, though more defined than Vino da Tavola.\ While the majority of Italy's most prestigious zones are in the north, the southern island of Ischia was awarded the country's second DOC in 1966, just a few months after Vernaccia di San Gimignano in Tuscany was granted the first. The south didn't have a DOCG until Taurasi was granted the distinction in 1993. Ten more years passed before two additional Campanian regions, Fiano di Avellino and Greco di Tufo, joined the DOCG ranks. Cerasuolo di Vittoria in Sicily and Colline Teramane in Abruzzo soon followed, as southern winemakers continued their march on quality.\ While some producers believe that too little regulation in the DOC system discourages quality production, others feel that too much regulation stifles creativity; and here is where Italian wines get a little more complicated. Some producers prefer to be classified as an IGT wine because they want to make wines outside of the strict guidelines of the DOC and DOCG. While an IGT classification carries restrictions, they are not as limiting as the DOC regulations, generally allowing for more experimentation. IGT wines made by bohemian winemakers can often be so distinctive that some of the most collected and sought-after wines in the market are classified IGT. Silvia Imparato makes one of Campania's cult wines, Montevetrano, using Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Aglianico grapes under the Colli di Salerno IGT designation.\ So winemakers are divided. The traditionalists produce wines that are admired for expressing the character of an area, and they are likely to be designated as DOC or DOCG wines. In contrast, modernist winemakers also plant native grapes, but they aren't afraid to blend them with international varieties. They are content with IGT status as long as they are permitted to make wines in their preferred style. Finding the best producers isn't always about following quality designations set by the government's classification system. Whether DOCG or Vino da Tavola, each viticultural area is only as strong as the current generation of winemakers working within it. This leaves wine lovers the rewarding task of venturing beyond the label to learn about the grapes, the regions, and the independent philosophies of winemakers.\ WINE DESIGNATIONS\ DENOMINAZIONE DI ORIGINE CONTROLLATA E GARANTITA (DOCG)\ This designation, which translates as "controlled and guaranteed place of named origin," asserts that only certain grapes from a designated area are used in a given wine. Of all the designations, this one is the most highly regulated and prestigious. DOCG wines are subjected to maximum-yield restrictions on the vineyards, minimum alcohol and acidity levels, and regimented aging requirements. Each DOCG also has to follow general guidelines on how the wine should taste, though there is often room for interpretation. For example, a wine from the Taurasi DOCG must be made with at least 85 percent Aglianico grapes, harvested from vines that are at least nine years old, and must be aged for at least three years, one of them in barrels. A Taurasi riserva is aged even longer-at least four years-and spends a year and a half in barrels. For this reason, a cellar such as Antonio Caggiano's has layers of dusty bottles waiting to be released onto the market.\ DENOMINAZIONE DI ORIGINE CONTROLLATA (DOC)\ This designation, which translates to "controlled place of named origin," regulates the same factors as a DOCG designation, such as permissible grapes, maximum yields, areas of production, and aging requirements. It is a lot harder to achieve DOCG status, however, so regulations are stricter in those zones than in DOCs. Unlike the Taurasi DOCG, for example, the Ischia DOC, off the coast of Campania, includes both white and red wines. The basic Ischia Bianco comprises primarily Biancolella and Forastera, with up to 15 percent of other local white grapes contributing to the blend. It must be aged in the bottle for just one month before being released. The Ischia Rosso is similarly flexible. Primarily made up of Guarnaccia and Piedirosso grapes (with other local red grapes rounding out the blend), it is bottle aged for a minimum of three months. The more relaxed requirements notwithstanding, producers often exceed the DOC standards. For example, Pietratorcia's Ischia Bianco is bottle aged for about four months before it is released.\ INDICAZIONE GEOGRAFICA TIPICA (IGT)\ The designation IGT, which translates as "typical to the geographical growing area," is the newest category among the four. It defines a broad regional area (generally much larger than a DOC zone) in which the wine production is loosely regulated. The Paestum IGT includes white, red, frizzante (semisparkling), and sweet wines made with grapes grown around the ancient city of Paestum in southern Campania. Bruno De Conciliis produces Selim, a sparkling wine made with Aglianico and Fiano grapes, under the Paestum IGT designation. The standard of quality for an IGT wine depends largely on the producer.\ VINO DA TAVOLA\ The broadest category, "table wine," signifies a wine produced in Italy, though generally the growing area is narrowed to a particular region. This designation can also be the escape route for winemakers whose wines clash with even the looser IGT regulations. Great wineries such as Planeta in Sicily make wonderful Syrah under the Vino da Tavola designation.\ CAMPANIA A16\ From the moment I first started tasting Campanian wines, they have captivated me. In fact, my excitement over these wines can be all consuming, leading me to plan overly ambitious research trips and forgo nearly every opportunity to wander around a village with the intention of getting lost in a Mezzogiorno moment. When visiting Campania, I keep the bustling pace of Naples even in sleepy, inland Taurasi or sunny Amalfi, because I can't seem to curb that feeling of adventure, the sense that the next road will lead to another wine epiphany. There are always new people to meet, old friends to visit with, and new wines to taste in too short a time to warrant a break.\ The energy pulsing through the region, coupled with growing interest in its singular wines, gives Campania the feel of a winemaking frontier. Yet as the ruins of Pompeii attest, Campania is hardly a wine newcomer. To grasp Campania's rich winemaking tradition, it is important to slow down and take a look back. Way back.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from A16 Food+Wine by Nate Appleman Shelley Lindgren Kate Leahy\ Copyright © 2008 by D.O.C. Restaurant Group, LLC. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.\ \

Contents Introduction....................1PART ONE: A16 WINE....................4CAMPANIA-A16....................15ABRUZZO-A24....................29MOLISE-A14....................33PUGLIA-A14....................35BASILICATA-SS658....................43CALABRIA-A3....................49SICILY-A20....................53SARDINIA-SS131....................61PART TWO: A16 FOOD....................66THE PANTRY....................72ANTIPASTI....................88PIZZA....................112ZUPPA....................126PASTA....................138SEAFOOD....................164POULTRY AND MEAT....................178THE PIG....................198VEGETABLES....................224DESSERT....................242RESOURCES....................268INDEX....................273

\ Publishers WeeklyOne of San Franciscoa's most popular new restaurants, A16 is devoted to southern Italya's rustic cuisine and robust wines. This book, by its executive chef and wine director, begins by exploring eight grape-growing areas in the south, from the regiona's heart in Campania to mountainous Abruzzo and the isolated island of Sardinia in the Mediterranean. With a dizzying number of wines produced in each area, the focus is wisely kept on the grapes themselves, with eloquent essays on the history and qualities of both classic and less familiar red and white varietals, and food pairing tips as well as recommendations of wine producers. The second half presents some of those foods-"peasant cooking" like pasta with chunky, chili-spiked sauce, a rabbit mixed grill and, of course, Neapolitan pizza, with A16a's Bay Area location showing in occasional ingredient twists like the tangerines in an arugula salad and the zesty punch of preserved Meyer lemon in a grilled shrimp dish. Executive chef Applemana's expertise is reflected in a chapter on "the pig," including recipes for making pancetta and sausages, which are rather advanced for casual home cooks but, like the rest of the book, make fascinating reading for lovers of Italian food and wine. (Sept.)\ Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalA16 is a San Francisco-based restaurant focusing on the regional Italian cuisine of Campania, and executive chef Appleman and wine director Lindgren feature many of the recipes served at the restaurant. The first section covers the wine varietals of southern Italy and includes descriptions of Italian wine designations; histories of the wines, food pairings, and producer recommendations are also here. The rest of the book is dedicated to food, beginning with an outline of the Campania cooking style. The pantry chapter has descriptions of foods common to southern Italian cuisine that are used at A16, and recipes for simple broths, flavored oils, and ricotta salata. It's important to read this section before starting any of the recipes as it explains seasoning rationale and has recipes for condiments/ingredients found later in the book. A resource list for ingredients and equipment is provided at the end of the book. A16 is a challenging specialty cookbook, coaxing readers to try unfamiliar ingredients and cooking techniques. An optional purchase for libraries with large cookbook collections.\ —Kimberly Bartosz\ \ \