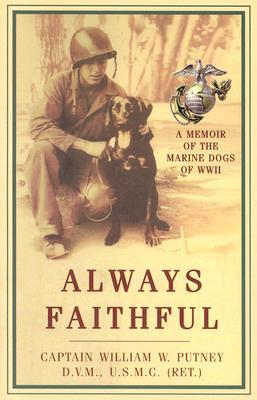

Always Faithful: A Memoir of the Marine Dogs of WWII

As a twenty-three-year-old veterinarian, William W. Putney joined the Marine Corps at the height of World War II. He commanded the Third Dog Platoon during the battle for Guam and later served as chief veterinarian and commanding officer of the War Dog Training School, where he helped train former pets for war in the Pacific. After the war, he fought successfully to have USMC war dogs returned to their civilian owners.\ Always Faithful is Putney’s celebration of the four-legged soldiers that...

Search in google:

Bill Putney, a licensed veterinarian, joined the Marines in 1943. As chief veterinarian at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, he trained dogs for combat. At the end of the war, he learned the dogs he'd served with were being put to sleep. He called for enabling military handlers to bring home the dogs they worked with. Library Journal A retired Marine Corps captain and veterinarian, Putney writes a moving and heartrending account of his days as commander of the 3rd Marine War Dog Platoon, in which some 72 dogs and their handlers were his responsibility. The dogs and handlers trained in scouting, mine detection, and other patrol duties and went into combat together. Here we read about Peppy, Big Boy, and Lady and a host of other courageous dogs who lived and died during some of the worst fighting of the war. Putney takes the reader through basic training and the battles of Guadalcanal and the retaking of the island of Guam in 1944. He continues the story of how those dogs that survived the war were retrained and returned to civilian life. For veterans and dog owners, the stories of heroism and death may be dreadful, but they are a reminder of the sacrifices needed to obtain victory in World War II. A unique animal and war story, this memoir is a tribute to all who cherish the loyalty and bonds that dogs give their owners. Recommended for all public libraries. David Alperstein, Queens Borough P.L., Jamaica, NY Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.

Prologue\ Less than twenty-four hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese invaded Guam, an American possession. The small Pacific island, virtually defenseless, held out for only four days. For the next two and a half years, the brave people of Guam endured a horrible occupation: they were starved, beaten, and herded into concentration camps. Many of Guam's people were summarily shot for crimes they did not commit. Some were beheaded. No other American civilians suffered so much under so brutal a conqueror.\ On July 21, 1944, the Americans struck back. The battle for Guam lasted only a few weeks, until August 10, 1944, when the island was declared secured. In those weeks, American Marine, Army, and Navy casualties exceeded 7,000. An estimated 18,500 Japanese were killed, and another 8,000 Japanese remained hidden in the jungle refusing to surrender.\ Among our dead were 25 dogs, specially trained by the U.S. Marines to search out the enemy hiding in the bush, detect mines and booby traps, alert troops in foxholes at night to approaching Japanese, and to carry messages, ammunition and medical supplies. They were buried in a small section of the Marine Cemetery, in a rice paddy on the landing beach at Asan that became known as the War Dog Cemetery.\ I was the commanding officer of the 3rd War Dog Platoon during the battle for Guam. Lieutenant William T. Taylor and I led 110 men and 72 dogs through training, first at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina; then at Camp Pendleton, California; later on Guadalcanal and then into battle on Guam.\ Most of the young Marines were assigned to the war dog program only by a twist of fate. Some had never owned a dog in their lives,and some were even afraid of them. But trained as dog handlers, they were expected to scout far forward of our lines, in treacherous jungle terrain, searching for Japanese soldiers hidden in caves or impenetrable thickets. Under these circumstances, the rifles we carried were often useless; a handler's most reliable weapons were his dog's highly developed senses of smell and hearing, which could alert him far in advance of an enemy ambush or attack, or the presence of a deadly mine, so he could warn in turn the Marines who followed behind at a safer distance. It was one of the most dangerous jobs in World War II, and more dogs were employed by the 2nd and 3rd Platoons on Guam than in all of the other battles in the Pacific.\ During the course of the war, 15 of the handlers in the 2nd and 3rd Platoons were killed: 3 at Guam, 4 on Saipan and 8 on Iwo Jima. These men were among the bravest and best-trained Marines of World War II, and were awarded the medals to prove it. During the course of some of the war's most vicious battles -- Guam, Saipan, Iwo Jima and Okinawa -- they were awarded five Silver Stars and seven Bronze Stars for heroism in action, and more than forty Purple Hearts for wounds received in battle.\ In these battles, as in their training, the men learned to depend on their dogs and to trust their dogs' instincts with their lives. Yet when I returned home from overseas, I found that rather than spend the time and expense to detrain the dogs, our military had begun to destroy them. Our dogs, primarily Doberman Pinschers and German Shepherds, had been recruited from the civilian population with the promise that they be returned, intact, when the war ended. Now, however, higher-ups argued that these dogs suffered from the "junkyard dog" syndrome: they were killers. Higher-ups were wrong. I lobbied for the right to detrain these dogs and won. Our program of deindoctrination was overwhelmingly successful: out of the 549 dogs that returned from the war, only 4 could not be detrained and returned to civilian life. Household pets once, the dogs became household pets again. In many cases, in fact, because the original, civilian owners were unable or unwilling to take the dogs back, the dogs went home with the handlers that they had served so well during the war.\ * * *\ More than fifty years have passed since the Battle of Guam. The dogs, of course, are long gone, and to the annual reunions fewer and fewer veterans of the war dog platoons return. Although it was a small chapter in the history of that worldwide conflagration, the story of the war dog platoons is significant. The dogs proved so valuable on Guam that every Marine division was assigned a war dog platoon and they paved the way for the many dogs that have followed them in the armed services, most famously in Vietnam.\ For their contribution to the war effort, the dogs paid a dear price, but the good they did was still far out of proportion to the sacrifice they made. They and their handlers led over 550 patrols on Guam alone, and encountered enemy soldiers on over half of them, but were never once ambushed. They saved hundreds of lives, including my own.\ This book is dedicated to the memory of those loving, courageous and faithful dogs of the 2nd and 3rd War Dog Platoons. They embodied the Marine Corps motto, Semper Fidelis.\ Rest in peace, dear ones.\ WILLIAM W. PUTNEY, D.V.M., CAPTAIN, USMC (RET.)\ WOODLAND HILLS, CALIFORNIA\ \ Copyright © 2001 by William W. Putney\ Chapter Six: Life Aboard Ship\ The SS Eugene Skinner was a Liberty ship, one of hundreds manufactured by wartime industrial wizard Henry Kaiser. By simply welding the metal plates of the sides and frame instead of fastening them with rivets, the production time for building a single ship went from months to a matter of days. In the early days of the war German and Japanese subs had been sinking vessels faster than the Allies could produce them; without Kaiser's innovation, America would not have been able to supply England with the wartime materials needed to stave off Germany until America could fully join the war.\ But, when I first saw the Skinner, I did not think about our incredible achievements of production, but of my selfish hopes for a first-class ocean voyage -- now forever dashed. She rode high in the water of San Diego Harbor listing decidedly to starboard, her sides rusty, and what paint was left on her hull peeling. Sergeant Hamilton assured me that once she had taken on fuel she would straighten right up, but to my eyes the Skinner was a sad-looking old scow. I concluded that I would be lucky if I made it to our final destination at all.\ The Skinner was manned by American merchant marines, the civilians that sailed merchant ships, freighters, tankers, and such. During World War II, thousands of them went down with their ships carrying supplies to our allies and our own armed forces. Our captain, who was Dutch, told Taylor and me that we were bound for Guadalcanal and our next stop would be New Caledonia. The captain had been in the Atlantic, where the most dangerous convoy work was, and had been sunk four times. This time we would sail alone -- the most hazardous way to travel -- and so take an indirect route by heading south, almost as far as the Fiji Islands, to avoid Japanese submarines. Due to the Skinner's slowness -- her top speed was eight knots an hour -- we wouldn't arrive for at least forty days.\ To board the Skinner, the dogs were removed from their crates, which were hoisted onto the ship and placed in one row on each side of the deck and faced outward. The men were assigned to the Skinner's forward hold, which had originally been designed for freight but had been "remodelled" to provide sleeping quarters for 150 troops. Bunks were stacked four-high along the starboard side, and the galley ran along the port side. Tables and benches occupied the center of the hold where the men could eat, play cards, read, or write letters. The hatch covering the hold had been removed and was replaced with canvas. There was no air-conditioning; instead, the canvas was rolled back on warm nights and sunny days to allow fresh air to enter the hold.\ Bill Taylor and I were assigned to the stateroom, topside. I stashed my gear in a corner and took off my field boots, and the moment I put my bare feet on the deck, they burned so badly I hastily retrieved my boots. Although more luxurious than the hold, our stateroom was located directly above the engine room: it was going to be a hot, humid trip.\ * * *\ Fifteen minutes into the trip, I got seasick. The ship felt as though it were rolling all over the ocean, but as I went to the head for the fourth time, I glanced out the porthole and saw, to my dismay, that we were still tied to the dock. Except for sick call for the dogs, I didn't emerge from the stateroom for three days. During the first few days, several of the dogs also suffered seasickness. We gave them Donnatal, a mixture of atropine and phenobarbital, but it didn't help them any more than it did me. Dogs and men were left to recover on their own.\ We soon settled into a daily routine. Reveille was at 6 A.M, but due to the limited facilities -- there were only ten toilets for over 110 men -- we were given a full hour to get ready for roll call, held on the afterdeck. The men were dismissed from formation, and during the next hour the dogs were removed from their crates and taken by squads to the fantail, the aptly named poop deck, the raised deck at the rear of the ship. A hose was available to wash down the deck afterward, although solid waste was deposited into GI cans that, along with the garbage from the galley and trash accumulated during the day, were dumped into the sea just before dark. The resulting trail of flotsam would be difficult to follow at night by enemy submarines, and by morning we would be miles away.\ At 8 A.M. the men fell back into ranks with their dogs, then peeled off by squads and ran in single file around the deck of the ship several times. Following the morning exercise, the dogs were returned to their crates and the men headed for breakfast. (The dogs were not fed until the afternoon.) Then the men swabbed down the toilet and shower area. They were freed from this task at 10 o'clock and returned to the afterdeck to remove their dogs from the crates and spend time with them.\ Lunch was served in two shifts, at 12:30 and 2 P.M., after which the men were required to wash their clothes and clean and oil their weapons to keep them from rusting in the damp, salty sea air. At 4:30 we all gathered on the deck for calisthenics, then the dogs were fed and dinner was served at 6:30. After dinner the men spent their time writing letters home which would be sent at the next port, playing cards, chatting, or reading a paperback book that had been provided by the Red Cross through the ship's library. Lights were out at 10:30.\ Every Friday we enlivened the monotony with an inspection of quarters and all personal gear by the officers -- meaning Taylor and myself. Uniforms had to be clean, carbines clean and oiled, and the men clean-shaven, with military haircuts. All the while, the Skinner slowly slogged on.\ The boredom of confinement at sea did have some beneficial side effects. Without encouragement, the men eagerly removed their dogs from their crates and played with them. The men spent hours teaching their dogs tricks, slowly learning every facet of their personalities. Hide-and-seek was a favorite game. At the command Search, the dogs would hunt down socks, belt buckles, K-Bar knives, or anything else hidden on the ship. Objects were concealed in old cardboard boxes stacked on the deck. When the objects were found, the dogs attacked the boxes with their front feet and literally tore them apart. In these unofficial exercises, Pfc. Keith Schaible's Butch was declared the champion. He could find anything that Schaible wanted him to find regardless of where it was hidden or by whom. Butch became so proficient at games that he was later able to locate mines and booby traps buried by the Japanese; he would prove unmatched in his ability to search caves for enemy soldiers or explosives.\ The dogs also acquired skills that, frankly, had no military purpose. Some were taught to walk on their hind legs, some on their front with their hind legs stuck up into the air. They learned to shake hands and to catch a piece of pogie bait in midair that had been placed on their noses or flipped upward at a handler's command. Pfc. Bob Johnson taught Spike to lift his leg and on command to urinate on anything -- or anyone -- next to him. Johnson's secret command was a particular way of twitching the leash that always went undetected by the unsuspecting victim.\ Sergeant Barnowsky had come aboard with a new puppy tucked into his jacket. Skeeter, as he came to be known, was a mongrel with a German Shepherd somewhere among his ancestors. Even before he was house-trained, Barney began teaching him basic obedience with one essential difference: Skeeter was trained to do everything backward. For example, when told to sit, Skeeter promptly stood up. Then Barney took the game one step further; when given one command, Skeeter would do the opposite until Barney turned his back. Then Skeeter would assume the correct position -- until Barney turned around again. The comedy act grew increasingly intricate as the voyage dragged on. Barney would tell Skeeter to sit up while on a table and Skeeter would go completely limp and slide slowly off the side. When pulled upright, Skeeter would collapse again. While Barney appealed in frustration to the audience, behind his back Skeeter would sit up or do his own tricks. The second that Barney returned his attention to Skeeter, the dog collapsed and Barney would have to catch him to keep him from falling to the deck.\ The Barney and Skeeter show was so entertaining that later in the war they were frequently asked to participate in shows for servicemen on the islands and ships of the Pacific. After the war I saw a professional dog trainer on stage in Las Vegas, Nevada, who went through the exact same routine to the delight of his audience. Had he cribbed from World War II's Barney and Skeeter show?\ The two dog platoons were not alone aboard the Skinner. Along with the merchant marine crew, there was an armed guard from the U.S. Navy commanded by Lieutenant Elvis A. Mooney, a former high-school principal from Bloomfield, Missouri. Mooney was in his mid-thirties, stocky and slightly overweight, with sandy-colored hair that was beginning to thin. Mooney was not by nature an officious man, but thought it integral to the persona of a naval officer that he become a student of naval protocol.\ Every morning, dressed in perfectly starched whites, Mooney went on his inspection tour. Along each side of the deck were two batteries of twin 50-millimeter antiaircraft guns, commonly called ack-ack guns, which, at an incredible rate, could throw up a barrage of automatic fire at an enemy aircraft should the situation demand it. Mooney's gunners sat in the chairs on the ack-ack guns or stood at attention beside the 5-inch gun as he walked by. If he found anything awry, he dressed down the offender with awful threats: "If it happens again, I'll nail your left ball to the yardarm." For Mooney, it was always the left ball, and never the right. Of course, it was an idle threat -- Mooney never disciplined anybody. When he wasn't visible, the crew mostly basked in the sun.\ One morning as Mooney made his tour all dressed out in his whites, he climbed the ladder to the fantail while the dogs were relieving themselves on the deck. Incensed at the desecration of our vessel, he yelled that it was a disgrace and ordered the place cleaned up immediately. He pointed the toe of his white shoe at the closest stool and turned to Pfc. Tex Blalock and screamed, "There's feces all over this deck."\ Blalock was an eighteen-year-old from Muleshoe, Texas. He was an intelligent Marine but had little formal education. When Mooney began yelling, Blalock became alarmed. "Feces! Feces!" he shouted. "I don't see no feces, sir!"\ Mooney pointed his toe again to a huge dog stool on the deck.\ Blalock's face brightened. Recognizing Mooney's mistake and wanting to set him straight, he cried delightedly, "Sir, sir, that ain't feces, that's dog shit!"\ Mooney reddened, turned on his heel and left.\ * * *\ About ten days after we'd put to sea, we ran into a huge tropical storm. The wind blew spray across the decks, which became awash as huge waves washed over the bow. At times the waves were so high that the bridge, the ship's highest point, seemed like a tiny tree amid mountains of water. The helmsman struggled to keep the ship from broaching as it fought to crest the tops of these cliffs, and the ship shuddered as it plunged through one wave after another, climbing laboriously to the top, plunging down the other side, burrowing its bow in the bottom of the trough, then starting all over again.\ We turned the doors of the dogs' crates aft to keep the salt water out and positioned a tarp in front of them as a shield. But the salt water did its damage: two days into the storm, Quillen showed me four dogs that had sore feet. The dogs walked gingerly across the deck, pausing to lick their feet frequently. The flesh between their toes and under their pads was red, inflamed and weeping. I washed the feet with fresh water, dried them and applied iodoform, a drying powder, between the toes and under the footpads. Then I bandaged them and sent the dogs back to their crates.\ The following day when the dogs were brought to sick call, I removed the bandaged feet only to find the condition had worsened. The tissue was more inflamed than before and the smell of rotten flesh -- the dogs' chewing kept the bandages wet and their tissues infected -- filled the air. When the bandages were left off, the dogs persisted in licking their wounds and the salt water continued to irritate the already irritated skin, making the condition worse.\ It was Quillen who came up with the solution. As I was cleaning one of the dog's feet, he said he'd be right back. The Corps, it seemed, had sent us off with extra boxes of condoms -- thousands of them. At the time the men had joked that the government had more faith in their charms than they had themselves. Quillen had discovered that either there had been a method to the Corps's madness or that we had gotten lucky. If I would bandage each foot and cover it with a "Merry Widow," it would stay dry.\ When Quillen returned, we put Duke on the crate that I was using as an examination table, cleaned his infected foot, dried it, powdered it liberally with iodoform, stuffed cotton between the toes and under the pads, rolled several courses of gauze around his paw and enveloped the whole thing in a condom, bound loosely with gauze and tape. I repeated the same treatment with the other dogs that had sore feet.\ By the next day the dogs' feet were drier and less inflamed. I continued the regimen, and by the time the sea had calmed several days later, I was able to leave the bandages off. With the absence of salt water soaking their feet and the cessation of their licking, the dogs' paws continued to improve and quickly returned to normal.\ There was one other casualty of the rough sea. Pfc. Ed Mullen had fallen and cut all of the tendons in his right wrist on pieces of a China crock he was carrying. In spite of catgut sutures that were suitable for dogs but too large for human tendons, I was able to reattach them, and Mullen regained use of all but his middle finger, which was later repaired at the naval hospital at New Caledonia.\ As the ship continued south, the weather growing slowly hotter, we removed the tarp from the front and sides of the dogs' crates, leaving only one over the top to provide shade. We turned the crates outboard, too, in hopes that a breeze might provide more ventilation. The heat in my stateroom had been bad at the beginning of the voyage, but as we progressed southward it became unbearable. I abandoned my torture chamber for the captain's doghouse, a cot covered by a small canvas tent just outside the bridge. The peak of the tent was only two feet above the cot, which allowed just enough space to slide in feet first and head last. The doghouse was meant for the captain to use as a place where he could catch a few winks when the ship was in dangerous water and he needed to be close to the bridge. But in his experience in hostile waters, the time lost in trying to get out of the doghouse and to the bridge would be more than could be spared if a crucial decision was necessary. He told me I was welcome to it. Taylor also abandoned the stateroom, surviving by throwing his mattress out on the deck outside the stateroom at night and back inside in the morning.\ One morning, seagulls appeared in the distance on the starboard of the ship. All hands rushed to the deck to watch the birds, knowing that we must be near land. Except for an occasional flying fish -- one flew so high that it landed on the deck, thirty feet above waterline -- this was the first animal life we had seen since leaving San Diego. The captain told us that the birds were coming from the Fiji Islands a hundred miles away, or possibly from some of the smaller islands south of Fiji. We would arrive in New Caledonia in five days.\ That same night, the man on the fantail watch reported a red light on our stern. Hearing the call, I crawled out of the doghouse and went to the bridge. Apparently, the word was passed to the hold because all hands were on deck with their eyes fixed on the blinking red light. The captain searched the area with his field glasses, and declared there was a Japanese submarine off our stern; it must have surfaced to charge its batteries. He had been expecting this since we entered the submarine lanes several days ago, and wondered what had kept the Japanese from appearing for so long.\ The sub was about a mile and a half or two miles behind us, but it was hard to tell because it was so dark. As long as the sub stayed that far back, we would be safe, but if it moved closer, we'd have to be ready to defend ourselves.\ I was more than a little concerned about this after having watched, only a few days earlier, when Lieutenant Mooney had ordered his gunners to shoot at a crate of garbage that the crew had thrown overboard. All hell broke loose as the 20-millimeter guns had burst into action, the tracer bullets stretching from the muzzles of the guns to the sea around the crate. For five minutes the racket kept up, but when Mooney had called a cease-fire, the crate bobbed along intact: not a single shell had penetrated it. He had then ordered the 5-inch naval gun on the fantail to fire on the target, and the whole ship had shuddered as the gun roared and black smoke rolled out of the muzzle. The shell hit at least a hundred yards short of its target, and a second attempt was so far off that the crate never got splashed.\ The captain, perhaps aware of the Skinner's firepower, thought it better not to provoke the vessel, adding that he didn't think it was interested in expending a torpedo on a small ship like the Skinner.\ For several more days and nights the sub stalked us, perhaps waiting for our ship to join a convoy so that the sub might have more prey. When it finally disappeared, Mooney thought the Japanese commander must have finally seen our 5-inch gun through his periscope and decided he was no match for the Skinner. I kept a straight face and my opinions to myself.\ As predicted by the captain, on the afternoon of the fifth day, the lookout sounded "Land ho, land ho," and we all rushed onto the deck to catch our first glimpse of a South Pacific island. Three hours and thirty minutes later, we steamed into the harbor at Nouméa, New Caledonia, the late afternoon sun outlining the island in light. I was pleased to see palm trees and a snowy white beach -- it looked exactly like all of the islands I had seen in movies about the South Pacific. A local pilot guided us through the channel, and as we got closer, buildings began to appear. They were not thatched huts; they were buildings just like those at home: brick, frame and stucco.\ After the ship dropped anchor, and as it was getting dark, Mooney and I clambered aboard a launch and headed for shore. All of my dreams of the beautiful South Sea islands were soon shattered by air filled with the aroma of raw sewage. Nouméa was the filthiest place I had ever seen.\ Mooney and I headed for the officers' club, located in the only large hotel. In the bar of the officers' club a Free French flag was hung alongside the flags of the United States, Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand. The British Empire was represented by officers from New Zealand and Australia, adorned in rakish, wide-brimmed hats pinned up on one side, and turban-wearing East Indians. There was even an occasional black officer from the Fiji Scouts, legendary for their battles against the Japanese in the Solomon Islands. The six-foot Fiji Scouts were known for creeping up on Japanese outposts, slashing the throats of unsuspecting sentries before their victims could utter a sound, and crawling silently away. I noticed that all of them wore long-sheathed knives attached to their Sam Brown belts even in the club.\ All of this was very exciting. Here were men who had fought the Japanese in the Solomon Islands, and I was desperately hoping to find out what things were like up there. I sauntered over to listen for what I hoped would be information I could use when I arrived in the war zone, but all I got for my snooping were drunken ramblings about the absence of women and tall tales of individual accomplishments. The chatter was the same that took place in gin joints and honky-tonks all over the world, the conversations only slightly more unintelligible because of too much cheap booze.\ The next morning I learned that for the seven days that we remained in the harbor at Nouméa, nobody would be able to swim because of lethal sea snakes that populated the waters. Aside from the dogs, the restriction made the biggest difference to Mooney and me, puffy-eyed and lethargic from the previous night of overindulgence. The air was hot and oppressive and there was no breeze flowing over the deck while we were at anchor. The Dobermans were slowly becoming acclimated to the tropical heat, but the longer-haired Shepherds required more time to adjust. To alleviate their suffering, the handlers frequently hosed them down with water in the late afternoon when whatever breeze had been blowing ceased altogether and the heat became stifling.\ We had one beautiful sable and white Collie, Tam, who suffered terribly. He panted constantly and even the hosing did not help a great deal. The chief steward loaned me an electric fan, which was kept running on Tam almost continually. It seemed to make him feel better, but after two days he developed a slight cough. Afraid of pneumonia, I reduced the fan's velocity and examined his throat and chest several times a day. The condition did not progress, and I was glad when we put to sea again, this time for Guadalcanal. I cursed the decision of someone back at Lejeune to send him with us, knowing we would be going to the tropics and that Tam would die of exhaustion if sent to race around the jungle at top speed delivering messages. Watching him suffer, I determined that he would be used only for night security, a job he could do effectively without inviting heat stroke. At one point I considered shaving his hair but rejected the idea because there was no shade and the tropical sun beating down on his bare skin would have been excruciating.\ We set sail for Bravo, which we now knew to be Guadalcanal, this time, however, in a convoy with other freighters, troopships and an escort of naval fighting ships. As these were hostile waters, we zigzagged our way northward for five days before dropping anchor.\ Copyright © 2001 by William W. Putney\ \

Prologue Chapter 1: Camp Lejeune, North Carolina Chapter 2: Training Chapter 3: Camp Pendleton, California Chapter 4: The Dog Men Chapter 5: The Last Days at Camp Pendleton Chapter 6: Life Aboard Ship Chapter 7: Guadalcanal Chapter 8: Landing Chapter 9: The Worst Day Chapter 10: Banzai Chapter 11: Mopping Up Chapter 12: Going Home Epilogue Acknowledgments

\ From Barnes & NobleWhen Bill Putney enlisted in the Marines as a 23-year-old licensed vet, he was assigned to the "Dog Corps." As the commanding officer of the 3rd War Dog Platoon, he helped train and later led America's dogs into combat in the invasion of Guam and other Pacific islands. When Putney returned home, he was shocked to discover that many of the animals he had served with were put to sleep, despite the military's promise to return them to the homes they'd been "drafted" from. Putney set out to fight for the dogs' right to come home, a tale told in a book that could be called Old Yeller meets The Greatest Generation.\ \ \ \ \ From the Publisher"A heart-rending story of courage and loyalty that should be celebrated." \ "A riveting account that brings together military and dog history in an unforgettable way and reaffirms the bonds that we keep with our four-legged friends."\ "Engrossing . . . You feel as if you were there watching the dogs being trained and going into combat. After the war was over, you find yourself cheering for the men who later fought military bureaucracy and misunderstanding to get these valiant dogs back to the families who volunteered them for service."\ "A fascinating and poignant story."\ \ \ \ Library JournalA retired Marine Corps captain and veterinarian, Putney writes a moving and heartrending account of his days as commander of the 3rd Marine War Dog Platoon, in which some 72 dogs and their handlers were his responsibility. The dogs and handlers trained in scouting, mine detection, and other patrol duties and went into combat together. Here we read about Peppy, Big Boy, and Lady and a host of other courageous dogs who lived and died during some of the worst fighting of the war. Putney takes the reader through basic training and the battles of Guadalcanal and the retaking of the island of Guam in 1944. He continues the story of how those dogs that survived the war were retrained and returned to civilian life. For veterans and dog owners, the stories of heroism and death may be dreadful, but they are a reminder of the sacrifices needed to obtain victory in World War II. A unique animal and war story, this memoir is a tribute to all who cherish the loyalty and bonds that dogs give their owners. Recommended for all public libraries. David Alperstein, Queens Borough P.L., Jamaica, NY Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.\ \