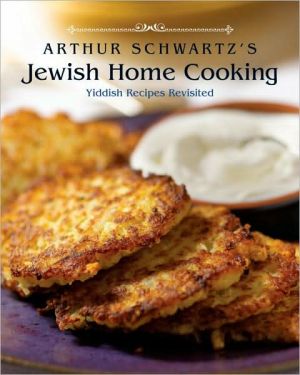

Arthur Schwartz's Jewish Home Cooking: Yiddish Recipes Revisited

Arthur Schwartz knows how Jewish food warms the heart and delights the soul, whether it's talking about it, shopping for it, cooking it, or, above all, eating it. JEWISH HOME COOKING presents authentic yet contemporary versions of traditional Ashkenazi foods-rugulach, matzoh brei, challah, brisket, and even challenging classics like kreplach (dumplings) and gefilte fish-that are approachable to make and revelatory to eat. Chapters on appetizers, soups, dairy (meatless) and meat entrees,...

Search in google:

Arthur Schwartz knows how Jewish food warms the heart and delights the soul, whether it's talking about it, shopping for it, cooking it, or, above all, eating it. JEWISH HOME COOKING presents authentic yet contemporary versions of traditional Ashkenazi foods-rugulach, matzoh brei, challah, brisket, and even challenging classics like kreplach (dumplings) and gefilte fish-that are approachable to make and revelatory to eat. Chapters on appetizers, soups, dairy (meatless) and meat entrees, Passover meals, breads, and desserts are filled with lore about individual dishes and the people who nurtured them in America. Light-filled food and location photographs of delis, butcher shops, and specialty grocery stores paint a vibrant picture of America's touchstone Jewish food culture. Stories, culinary history, and nearly 100 recipes for Jewish home cooking from the heart of American Jewish culture, New York City. Written by one of the country's foremost experts on traditional and contemporary Jewish food, cooking, and culinary culture. Schwartz won the 2005 IACP Cookbook of the Year.Reviews & AwardsJames Beard Foundation Cookbook Award Finalist: American Category IACP International Association of Culinary Professionals Cookbook Awards, American Category Finalist "Jewish Home Cooking helps make sense of the beautiful chaos, with a deep and affectionate examination of New York's Jewish food culture, refracted through the Ins of what he calls the Yiddish-American experience."—New York Times Book Review Summer Reading issue, cookbook roundup“Schwartz breathes life into Yiddish cooking traditions now missing from most cities' main streets as well as many Jewish tables. His colorful stories are so distinctive and charming that even someone who has never heard Schwartz's radio show or seen him on TV will feel his warm personaality and love for food radiating from the page . . . Cooks and readers from Schwartz's generation and earlier, who know firsthand what he's talking about, will appreciate this delightful new book for the world it evokes as much as for the recipes.”—Publishers Weekly The New York Times - Sam Sifton …helps make sense of the beautiful chaos, with a deep and affectionate examination of New York's Jewish food culture, refracted through the lens of what he calls the Yiddish-American experience…[Schwartz's] stories about New York foodways are learned and funny. Amid them, he offers definitive, simple and deadly effective recipes

ARTHUR SCHWARTZ'S Jewish Home Cooking\ Yiddish Recipes Revisited \ \ \ By ARTHUR SCHWARTZ'S \ TEN SPEED PRESS \ Copyright © 2008 \ Arthur Schwartz\ All right reserved.\ \ ISBN: 978-1-58008-898-5 \ \ \ \ \ Chapter One Appetizers \ An appetizer is called a forshpeiz in Yiddish. But a forshpeiz to an alter kocker (old-timer, in Yiddish) might be so copiously portioned that it could be a whole meal to a Gentile, or to a buff boychik of today.\ After generations in poverty, Jews from the little villages of Eastern Europe, the shtetls, came to New York to live the American Dream. They viewed their ability to eat as much as they wanted as a sign of their affluence and of their particular zest for the good life in America. New York Jews would even make jokes about how little food Gentiles ate (except Italians), or how they didn't know how to eat.\ How do you know who the WASPs are at a Chinese restaurant? They're the ones not sharing their food.\ After World War II, at Jewish wedding and bar mitzvah receptions in New York, guests would first encounter a smorgasbord of "appetizers," meaning a buffet with cold foods, hot foods in chafing dishes, and special food stations serving roasts carved to order and even crêpes made on the spot. Then came a five- to seven-course sit-down dinner. It's not much different now, except a sushi station has replaced the crêpes, and at bar or bat mitzvahs, pizza is a requirement for the guest of honor and friends.\ Sometimes Jewish appetizers are actually main courses, only in slightly smaller portions. Stuffed Cabbage (page 118) goes either way, as does sweet-and-sour tongue, brown-sauced sweetbreads and mushrooms (page 36), and chicken-giblet fricassee with tiny meatballs (page 29). All of them are, in truth, more appropriate after something else than before, but so it goes at the Yiddish table.\ Arbes\ Seasoned Chickpeas\ Long before American Jews knew about hummus, the Arab chickpea puree that, ironically, has become one of the national dishes of Israel, chickpeas were a "Jewish" food, even among the Ashkenazim of Central and Eastern Europe. The legume is mentioned in the Bible (Daniel 1:12), and it is a symbol of regeneration, which is why chickpeas are served at a sholom zachar. That's a festive gathering held in some Jewish communities on the first Friday night after a boy is born. Friends and family toast the parents and child, and no matter whatever else is served, they nosh on arbes and salute life (l'chaim) with beer.\ Chickpeas are also traditionally served at Purim, the holiday that commemorates the rescue of the Jews from genocide by the Persian Jewish queen, Esther. Queen Esther became a vegetarian so she could live at court and remain kosher, and not divulge that she was Jewish. Chickpeas were among the foods she ate, along with seeds and nuts, hence the custom of eating poppyseed-filled Hamantaschen (page 237) on Purim.\ I remember arbes (in Polish Yiddish, nahit in Russian Yiddish) from Ratner's and Rappaport's, the most important dairy restaurants on the Lower East Side. A bowl of chickpeas bursting from their skins, salted and well peppered, was on the table when you sat down, like the pickle bowl at the deli. You ate them with your hands, like nuts.\ At Purim and birth celebrations, chickpeas are often tossed or drizzled with honey instead of a savory seasoning. For variety beyond just salt and pepper, you can season arbes lightly with ground cumin or flakes of red Aleppo (Syrian or Turkish) pepper, which combines sweet and fiery flavors, or both.\ Canned chickpeas, drained, rinsed, and dried with a paper towel, make excellent arbes. To cook dried chickpeas, first soak them in water-start with hot-for at least 8 hours, then boil them, uncovered, in fresh water for at least 1 1/2 hours, until they are very tender and their skins begin to burst. They may seem overcooked when the skins burst, but they will firm up again when cooled.\ Chopped Eggs and Onions\ The usual name for this egg salad is deceptive. Much of its appeal comes from the unmentioned ingredient, schmaltz. You must have good schmaltz to elevate what would otherwise be an ordinary egg salad. Even better, if you add some griebenes (chicken cracklings, see page 10) it becomes divine and very dangerous stuff that you won't be able to stop eating. As an appetizer, serve this dish as a spread with crackers. As a first course at the table, or for a light meal, pair it with cut up raw vegetables like sliced cucumbers and tomatoes (or cherry tomatoes), whole scallions, and red radishes. It is particularly good with black bread or pumpernickel, but challah or matzo is excellent, too. In fact, in some households, this salad is the first course of Shabbos dinner, served with the braided challah, over which a blessing has been made giving recognition to G-d for providing us with food.\ Instead of onion, you can use minced scallions. Some cooks prefer to sauté the raw onion before adding it to the eggs. That's delicious, too, but another dish entirely. Speaking of another dish entirely, the salad is, of course, delicious with mayonnaise, too.\ The texture of this salad is best when the eggs are chopped by hand with a large, sharp knife on a board, or in a wooden chopping bowl using a hochtmesser, a curve-bladed chopper, like an Italian mezzaluna. For egg salad, a pastry blender in a wooden bowl also works well because the eggs are soft.\ Serves 2\ 4 hard-cooked eggs, peeled 1 very small onion, finely chopped (about 1/3 cup) 1 rounded tablespoon Schmaltz (page 9) Salt and freshly ground black pepper\ Place the whole eggs and chopped onion on a board or in a chopping bowl. Chop the eggs and onions together until the eggs are the desired consistency. If you have been using a chopping board, transfer the mixture to a bowl.\ Add the schmaltz, and season with salt and freshly ground black pepper. With a fork, gently combine with the egg mixture, being careful not to mash the eggs too much.\ Serve at room temperature. The salad can be refrigerated, tightly covered, for 1 day, but should be eaten at room temperature.\ Chopped Herring Salad\ Here's an example of the famous Litvak-Galitzianer gastronomic divide (see page 32): the Russ family, which owns Russ & Daughters, the landmark appetizing store, are proud Galitzianers, Jews who were originally from Galicia, a region in East Central Europe now divided between Poland and Ukraine. They make their chopped herring salad with the sole addition of tart green apple and nothing more. My maternal grandmother, whose parents (not she) hailed from a shtetl near Minsk, was a proud Litvak (a Jew of Lithuanian or Russian descent). She prepared her chopped herring with chopped hard-cooked egg as the only addition and nothing more.\ Chopped herring was always among my grandmother's appetizers for her annual Chanukah party, as well as other festive occasions. Chopped herring, actually any herring, was considered the perfect accompaniment to schnapps, a word that covers all strong alcoholic spirits. In reality, however, to middle class New York Jews of those days, it meant only Scotch or rye whiskey, or maybe Canadian whisky, plus Cherry Heering for the ladies. Vodka hardly existed then; bourbon was, at least to my grandfather Louis Sonkin, "country club whiskey," which meant for Gentiles only. And no one we knew drank martinis, based on gin as they always used to be, although herring and gin are a natural combination.\ Chopped herring also appeared frequently on our Sunday breakfast table along with bagels, lox, cream cheese, and the other pickled and smoked fish from the appetizing store (see page 1). I still like to spread cold herring salad on a warm bagel, and this combo remains an option at most New York City bagel bakeries that make sandwiches and provide a schmear of this or that.\ As a formal first course, serve a scoop of herring salad on a plate lined with lettuce and garnished with the usual raw vegetables-cucumber, radish, tomato, scallions. Pumpernickel and black bread are traditional and excellent accompaniments. Seeded rye and Corn Bread (page 205), even matzo or crackers, are great, too.\ Makes about 21/2 cups, enough for 6 to 8 as a snack with drinks\ 2 cups well-drained jarred herring fillets in "wine sauce" or snacks (smaller pieces of herring) in "wine sauce," including the pickled onion 3 or 4 hard-cooked eggs, peeled Bread or crackers, as accompaniment\ In the bowl of a food processor fitted with the metal blade, combine the herring with the bits of onion (from the jar) and the whole, hard-cooked eggs. (Use 3 eggs for a stronger herring taste, 4 eggs for a slightly milder flavor.) Pulse until the ingredients are finely chopped and hold together as a paste.\ Chill well before serving with bread or crackers. The chopped herring should keep well in the refrigerator for at least several days.\ Smothered Onions\ It is written that the manna from heaven that sustained the Jews during their forty years of wandering in the desert could have any flavor one imagined it to have, except for onions and garlic. Does this have something to do with why onions and garlic play such an important role in all Jewish cuisines?\ In any case, onions apparently grew well in the shtetls of cold-climate Poland and Russia. Grated, chopped, and sliced; raw or fried anywhere from lightly golden to a deep caramel brown; cooked in schmaltz, in butter, in peanut, corn, or canola oil, and, unfortunately (in the modern American kitchen), in margarine and solid white shortening, onions are an important ingredient in the Yiddish pantry.\ You could say onions are a defining flavor, in the sense that some dishes rely so heavily on onions that they wouldn't taste Jewish without them.\ Chopped liver immediately comes to mind. In fact, I'd say mock chopped liver, the vegetarian version, relies mainly on fried onions to resemble the real thing. And there's mushrooms and egg barley, kasha varnishkes, and knish and blintz fillings, as well as lox, eggs, and onions, to name a few more. Potato kugel and potato latkes would be insipid without onions.\ At many of the old-time Jewish meat restaurants, you could order fried onions à la carte, a bowlful to strew wherever you pleased.\ When I was boy, my mother always ordered her hamburgers and my father his steaks with smothered onions. Nowadays, if you ask for smothered onions the waiter will be bewildered. You could request fried onions, but caramelized is the fashionable name. It's all the same: they are onions that are wilted and cooked until golden, deeply browned, or even almost burnt.\ Many of the recipes in this book start with this process. Sometimes you will want to make them specifically for a recipe, in which case it's good to, for example, fry the mushrooms in the same pan-don't clean it yet-used to cook the onions. The flavor the onions leave on the bottom of the pan should not be wasted. Somehow, incorporate it into your dish. In some cases, you can pour in a little liquid (deglazing, to a professional chef) and scrape up this glaze into the liquid used in the recipe.\ To smother (fry) onions, first either chop or slice the onions according to the recipe instructions. Add enough schmaltz, butter, or peanut, corn, or canola oil to cover the bottom of a covered skillet or sauté pan large enough to comfortably hold the onions. (A 10-inch pan will usually hold up to 2 pounds of onions-about 6 cups-and will require about 3 tablespoons of fat.) Heat the fat over medium-high heat.\ Add the onions and toss in the hot fat; cover the skillet, decrease the heat to medium, and let the onions sweat for 10 minutes, tossing them once after 5 or 6 minutes. Uncover the pan and stir the onions; they will have begun to brown.\ Increase the heat to medium-high and continue to fry the onions, uncovered, for at least 20 minutes more for browned onions, about 30 minutes more for dark-brown onions. Stir the onions every 3 to 4 minutes as they cook, scraping up the residue on the bottom of the pan. (I like to use a straight-edged wooden spatula for this.) The onions may need more frequent stirring as they brown. If the underside of the onions aren't browning after 4 minutes, increase the heat.\ The fried onions can be stored in the refrigerator, tightly covered, for a couple of weeks, so it pays to do a lot at once.\ Schmaltz\ Rendered Chicken Fat\ The smell of schmaltz always reminds me of my early childhood in Brooklyn. My mother and grandmother started saving schmaltz for Pesach weeks before, probably right after Purim. Since it was still cold outside, they stored it in a bag that hung near the electric lines outside my bedroom. Sometimes, of course, it got a little warmer and the fat began to melt. For years after, there remained a large black stain under that section of the window from the melting schmaltz! -A memory of Martha Usdin\ My grandparents and other relatives all lived in Brooklyn, though my parents relocated to Kingston, New York, where I grew up. I remember taking the Trailways bus from Kingston to my grandmother's apartment in Bensonhurst. When it was time to take the bus home, she would prepare a meal for me. She'd take a hard roll, remove almost all of the bread from the inside, and fill it with chicken schmaltz and chicken. What a thing that was! -A memory of Greta Ginzburg\ The aroma of chicken fat rendering on the stove, or anything being cooked in chicken fat, is one of those sensory cues that brings back memories of cuddly Jewish grandmas. It was the most important cooking fat in old-time Jewish kitchens, and it is another defining flavor in the Yiddish kitchen. Although we rarely fry with it today, preferring less saturated vegetable oils, it is still a necessity for flavor. What are Knaidlach (page 43) without it? Just any old dumplings. Chopped Liver (page 11) has to have it (at least a little). Kasha Varnishkes (page 85) and Mushrooms and Egg Barley (page 87) are so much better with it. In the old days, it was even used as a spread-on matzo during Passover, on challah on the Sabbath, and on rye bread any other day of the week.\ The word for rendered chicken fat in Yiddish is "schmaltz," but the word is also used figuratively to mean something that is overly sentimental or overblown in a less than tasteful way. You might say cloying, as in an orchestral arrangement with an excess of strings (like those by Mantovani) or a melodramatic, tearjerker movie (I'll Cry Tomorrow).\ Few chickens these days have the big clumps of fat they used to, but even in my grandmother's day it was always necessary to collect fat from quite a few chickens to have enough to render. For use at Passover these days, starting the fat collection a month earlier at Purim, as in Marsha Usdin's memory, would no longer be time enough. I collect fat in a plastic bag that I keep in the freezer for up to three months. I pull off the clumps of fat, and trim off and save the excess fatty skin from the whole chickens I cook.\ Use the griebenes (cracklings) and darkly caramelized onions that you have strained out to season Chopped Liver (page 11), Kasha Varnishkes (page 85), mashed potatoes, the mashed potato filling for Knishes (page 90), Mushrooms and Egg Barley (page 87), Potato Kugel (page 76), or fleishig lukshen kugel or Matzo Farfel Kugel (page 174). Or, salt the griebenes and eat it for its own sake as a treat.\ When I have saved about 2 cups of fat in my freezer, I render it. You can render the fat and turn the skin into griebenes while still frozen.\ Makes about 2 cups schmaltz\ 2 cups chicken fat 1 medium onion, thinly sliced\ Chop the frozen pieces of fat coarsely, then put them in a skillet with enough water to barely cover. Place over low heat. The fat will start liquefying when the water begins to simmer.\ When the fat appears about half rendered and the water has evaporated, add the onion. Continue to cook over low heat until the cracklings and onion are well browned.\ Pour the fat through a strainer into a jar. It will keep in the refrigerator, tightly covered, for several months. Save the onions and griebenes to flavor dishes, or, if you dare, eat them as is, sprinkled with salt.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from ARTHUR SCHWARTZ'S Jewish Home Cooking by ARTHUR SCHWARTZ'S\ Copyright © 2008 by Arthur Schwartz. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.\ \

Contents Introduction....................viiChapter 1 Appetizers....................1Chapter 2 Soups....................39Chapter 3 Side Dishes....................69Chapter 4 Meat Main Courses....................101Chapter 5 Dairy Main Courses....................143Chapter 6 Passover....................169Chapter 7 Breads....................193Chapter 8 Desserts and Sweet Baking....................217A Glossary of Yiddish Food Terms....................254Acknowledgments....................262Index....................264

\ Sam Sifton…helps make sense of the beautiful chaos, with a deep and affectionate examination of New York's Jewish food culture, refracted through the lens of what he calls the Yiddish-American experience…[Schwartz's] stories about New York foodways are learned and funny. Amid them, he offers definitive, simple and deadly effective recipes\ —The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklySchwartz (Arthur Schwartz's New York City Food) breathes life into Yiddish cooking traditions now missing from most cities' main streets as well as many Jewish tables. His colorful stories are so distinctive and charming that even someone who has never heard Schwartz's radio show or seen him on TV will feel his warm personality and love for food radiating from the page. Oddly, even the shorter anecdotes often run longer than the actual recipes; anyone intending to cook from the book should have some kitchen experience or risk frustration at the often brief instructions. Dishes run the gamut from beloved appetizers like gefilte fish to classic meat and dairy main items (cholent, blintzes), plus less familiar items like onion cookies and Hungarian shlishkas (light potato dumplings). Schwartz intersperses engaging commentary on everything from farfel and matzo to Romanian steakhouses and why Jews like Chinese food. Those with Westernized palates may recoil at the thought of gelled calf's feet, but Schwartz shows how stereotypically heavy Ashkenazi food can be improved and made at least somewhat lighter when prepared properly. Cooks and readers from Schwartz's generation and earlier, who know firsthand what he's talking about, will appreciate this delightful new book for the world it evokes as much as for the recipes. (Apr.)\ Copyright 2007 Reed Business Information\ \ \ Library JournalSchwartz, author of several cookbooks, including New York City Food, presents 100 or so recipes for classic Jewish dishes, e.g., Gefilte Fish, Flanken, Kreplach, Hamantaschen. This is the food of Ashkenazi Jews (as opposed to Sephardim)-i.e., the eastern European Jews who spoke Yiddish. Many readers will remember their grandmothers cooking these dishes, which today are often reserved for (or relegated to) holiday meals; Schwartz wanted both to rescue almost-forgotten dishes and to update these traditional recipes to make them healthier and somewhat more contemporary ("a lessening of the schmaltz here, a tweak there"). His lengthy, informed, and readable headnotes provide background, and there are sidebars throughout on ingredients and various intriguing topics (Who knew Heinz vegetarian beans were the first commercial products to be certified kosher, in 1923?-its ketchup was the second, in 1924). Useful as both a reference and a cookbook, this is strongly recommended.\ —Judith Sutton\ \ \