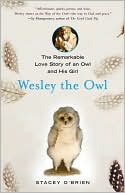

Avoid Boring People: Lessons from a Life in Science

From Nobel Prize—winning scientist James D. Watson, a living legend for his work unlocking the structure of DNA, comes this candid and entertaining memoir, filled with practical advice for those starting out their academic careers.\ In Avoid Boring People, Watson lays down a life's wisdom for getting ahead in a competitive world. Witty and uncompromisingly honest, he offers young scientists advice on choosing the right projects, and shares his thoughts on the supreme importance of...

Search in google:

From a living legend—James D. Watson, who shared the Nobel Prize for having revealed the structure of DNA—a personal account of the making of a scientist. In Avoid Boring People, the man who discovered “the secret of life” shares the less revolutionary secrets he has found to getting along and getting ahead in a competitive world.Recounting the years of his own formation—from his father’s birding lessons to the political cat’s cradle of professorship at Harvard—Watson illuminates the progress of an exemplary scientific life, both his own pursuit of knowledge and how he learns to nurture fledgling scientists. Each phase of his experience yields a wealth of age-specific practical advice. For instance, when young, never be the brightest person in the room or bring more than one date on a ski trip; later in life, always accept with grace when your request for funding is denied, and—for goodness’ sake—don’t dye your hair. There are precepts that few others would find occasion to heed (expect to gain weight after you win your Nobel Prize, as everyone will invite you to dinner) and many more with broader application (do not succumb to the seductions of golf if you intend to stay young professionally). And whatever the season or the occasion: avoid boring people.A true believer in the intellectual promise of youth, Watson offers specific pointers to beginning scientists about choosing the projects that will shape their careers, the supreme importance of collegiality, and dealing with competitors within the same institution, even one who is a former mentor. Finally he addresses himself to the role and needs of science at large universities in the context of discussing the unceremonious departure of Harvard's president Larry Summers and the search for his successor.Scorning political correctness, this irreverent romp through Watson’s life and learning is an indispensable guide to anyone plotting a career in science (or most anything else), a primer addressed both to the next generation and those who are entrusted with their minds. Marianne Stowell Bracke - Library Journal Watson and Francis Crick, along with other lesser-known scientists (see Brenda Maddox's Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA), will forever be remembered as the discoverers of the double helix structure of DNA in the 1950s. Since then, Watson, currently chancellor at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York State, has remained an active participant in academics and scientific research. Part memoir, part essay on life, Watson's latest book (after Genes, Girls and Gamow) is surprisingly wry, witty, and instructional as he shares lessons and offers useful advice-hard-won through years of experience navigating the politics of academia and the scientific community-that runs from the humorous (e.g., "manage your scientists like a baseball team") to the wise (e.g., "ask the dean only for what he can give"). He also recognizes the need for bridging the worlds of science and nonscience to share big discoveries that can have a major impact on both spheres. He is concerned with educating future scientists on ways to balance life in and out of the laboratory for the benefit of all. Recommended for all academic and public libraries.

Remembered Lessons from Childhood on Chicago's South Side\ 1. Avoid fighting bigger boys or dogs\ As a child I lived with being punier than other boys in class. The only consolation was my parents' empathy—they encouraged constant trips to the local drugstore for chocolate milk shakes to fatten me up. The shakes made me happy, but still all through grammar school other kids shoved me around. At first I responded with my fists, but soon I realized that being called a sissy was a better fate than being beaten up. It was easier to cross to the other side of the street than come face-to-face with loitering menaces with a nose for my fear. Likewise, I was no match for barking dogs, particularly ones I had provoked by climbing over fences into their domains. Spotting a rare bird is never worth the bite of a cur. Once bitten by a German shepherd, I knew that I preferred cats, even if they are bird-killers. Life is long enough for more than one chance at a rare bird.\ 2. Put lots of spin on balls\ I long wanted to be part of the softball games played on the big vacant lot across Seventy-ninth Street. At first my only way to join in was to field foul balls. Then I learned how to put spin on underhanded pitches that kept even the better batters from routinely smacking line drives through holes in the outfield. From then on I felt much less an outsider on Saturday mornings. The spins that came from similarly slicing ping-pong serves helped make me a good player well before my arms got long enough to reach near the net of our family’s basement table.\ 3. Never accept dares that put your life at risk\ Seeing classmates dash across a street to beat a coming car filled me with more horror than envy of their bravado. When I rode my bike three miles to the Museum of Science and Industry, I knew my constantly worrying mother would have preferred my taking the streetcar. But by being cautious—going down as many alleys as possible and never taking my hands off the handlebars when a car was passing—I was never really putting my life at significant risk. Likewise, in climbing up and over the branches of neighborhood trees or hoisting myself up along gutters to the roofs of one-story garages, I may have been risking a broken leg but not a fatal fall. The possibility of plunging more than ten feet never seemed worth the thrill of being high up.\ 4. Accept only advice that comes from experience as opposed to revelation\ Listening to my elders just because they were older was not the way I grew up. Preadolescent exposure to my relatives’ views that the New Deal would bankrupt the United States and that Hitler would cease being an aggressor after conquering England left me with no illusions that adults are less likely than children to utter nonsense. For the most part, my parents tried to provide rational explanations for why I should think a certain way or do a certain thing. So I was convinced by my mother’s advice that I wear rubbers on rainy days so as not to ruin my leather soles. At the same time, I rejected her no less often heard argument that sodden feet led to colds.\ By then I was conditioned to accept my father’s disdain for any explanations that went beyond the laws of reason and science. Astrology had to be bunk until someone could demonstrate in a verifiable way that the arrangement of the stars and planets affected the course of individual lives. Equally improbable to Dad was the idea of a supreme being, the widespread belief in whose existence was in no way subject to observation or experimentation. It is no coincidence that so many religious beliefs date back to times when no science could possibly have accounted satisfactorily for many of the natural phenomena inspiring scripture and myths.\ 5. Hypocrisy in search of social acceptance erodes your self-respect\ My parents and most of their neighbors had nothing bonding them together but Horace Mann Grammar School. Mother, with an outgoing and generous personality, naturally rose to be president of the PTA. But except for a keen interest in baseball, Dad had nothing in common with his fellow fathers. That love, however, seldom drew him into the backyards of neighbors, where frequent blasts at the New Deal and occasional anti-Semitic jokes were insufferable for Dad, whose favorite radio personality besides Franklin Roosevelt was the Jewish intellectual Clifton Fadiman. He knew enough to avoid occasions where polite silence in response to repulsive remarks could be construed as acquiescence in their awfulness.\ 6. Never be flippant with teachers\ My parents made it clear that I should never display even the slightest disrespect to individuals who had the power to let me skip a half grade or move into more challenging classes. While it was all right for me to know more about a topic than my sixth-grade teacher had ever learned, questioning her facts could only lead to trouble.Until one has cleared high school there is little to be gained by questioning what your teacher wants you to learn. Better to memorize obligingly their pet facts and get perfect grades. Save flights of rebellion for when authority does not have you by the throat.\ 7. When intellectually panicking, get help quickly\ Occasionally I found myself nervously distraught, unable to repeat an algebraic trick I had learned the previous day. I never hesitated in such circumstances to turn to a classmate for help. Better for one of them to know my inadequacies than not to be able to go on to the next problem. “Do it yourself or you’ll never learn” may have some validity, but fail to get it done and you’ll go nowhere. Even more frequently I was unable to express myself in words and habitually procrastinated with writing assignments. It was only with my mother’s last-minute help that I punctually submitted a well-written eighth-grade paper on the history of Chicago. Of much greater importance was Mother’s later insistence that she edit every word of my scholarship essay to the University of Chicago. I accepted her extensive editing with little guilt, then or since.\ 8. Find a young hero to emulate\ On one of our regular Friday night visits to the Seventy-third Street public library, my father encouraged me to borrow Paul de Kruif’s celebrated 1926 book, Microbe Hunters. In it were fascinating stories of how infectious diseases were being conquered by scientists who went after bad germs with the same tenacity as Sherlock Holmes pursuing the evil Dr. Moriarty. Some months later I brought home Arrowsmith, in which Sinclair Lewis, helped by Paul de Kruif as expert consultant, relates the never-realized hope of his hero to save victims from cholera by treating them with bacteria-killing viruses. The protagonist’s youth gripped me and made me realize that science could be like baseball: a young man’s game whose stars made their mark in their early twenties.\ Also encouraging me to aim high was my not-too-distant cousin Orson Welles, whose grandmother was a Watson. Though we never met, he also had an Illinois background and after being effectively orphaned was partly raised by my father’s uncle, the celebrated Chicago artist Dudley Crafts Watson. Always turned out with much panache, including a pince-nez, Dudley relished telling his nephew’s family of Orson’s triumphs, which began when he was a child actor in the Todd School. Orson’s daring was what appealed to me most, from his famous War of the Worlds radio hoax to his groundbreaking feature Citizen Kane. A scientist’s hero need not be a microbiologist, let alone a baseball player.

Foreword ixPreface xi1 Manners Acquired as a Child 32 Manners Learned While an Undergraduate 213 Manners Picked up in Graduate School 384 Manners Followed by the Phage Group 555 Manners Passed on to an Aspiring Young Scientist 726 Manners Needed for Important Science 947 Manners Practiced as an Untenured Professor 1188 Manners Deployed for Academic Zing 1369 Manners Noticed as a Dispensable White House Adviser 15510 Manners Appropriate for a Nobel Prize 17311 Manners Demanded by Academic Ineptitude 19512 Manners Behind Readable Books 21313 Manners Required for Academic Civility 24014 Manners For Holding Down Two Jobs 25915 Manners Maintained When Reluctantly Leaving Harvard 286Epilogue 316Cast of Characters 329Remembered Lessons 343

\ From Barnes & NobleMolecular biologist James D. Watson, the co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, is one of the most famous scientists alive. He's also one of the most gifted and accessible writers among Nobel Prize-winning scientists. His 1968 book, The Double Helix, is a true science classic, one of the Modern Library's 100 Hundred Best Nonfiction Books. As its title suggests, Watson's "memoir and more" makes no pretense of undue solemnity; its 79-year-old author is too wise and contented to suppress his bubbling opinions. Avoid Boring People is a superb choice for readers who like to do the same.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalWatson and Francis Crick, along with other lesser-known scientists (see Brenda Maddox's Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA), will forever be remembered as the discoverers of the double helix structure of DNA in the 1950s. Since then, Watson, currently chancellor at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York State, has remained an active participant in academics and scientific research. Part memoir, part essay on life, Watson's latest book (after Genes, Girls and Gamow) is surprisingly wry, witty, and instructional as he shares lessons and offers useful advice-hard-won through years of experience navigating the politics of academia and the scientific community-that runs from the humorous (e.g., "manage your scientists like a baseball team") to the wise (e.g., "ask the dean only for what he can give"). He also recognizes the need for bridging the worlds of science and nonscience to share big discoveries that can have a major impact on both spheres. He is concerned with educating future scientists on ways to balance life in and out of the laboratory for the benefit of all. Recommended for all academic and public libraries.\ —Marianne Stowell Bracke\ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAge cannot whither nor custom stale the sharp tongue of "Honest Jim"-the title the Nobel Prize-winning Watson (DNA: The Secret of Life, 2003, etc.) originally wanted for The Double Helix, his first tell-all account of science and personal history. Now in his late 70s, Watson chronicles his life from birth through middle age. We learn of a close-knit family and an early love of ornithology, but the even greater appeal of genetics by the time of graduate school. Watson's career took off as he began working with hot-shot geneticists studying bacterial viruses (phages) like the future Nobelists Salvador Luria and Max Delbruck. Indeed, the names of Watson's mentors, peers and former graduate students read like a Who's Who in molecular biology. They also underscore some of the "remembered lessons" he adds to each chapter, e.g., "choose a young thesis advisor"; "choose an objective apparently ahead of its time." The main text deals with the years Watson taught at Harvard and later when he became director of the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island, moving it from near bankruptcy to growth and continued pre-eminence. Watson has certainly made his mark as scientist, teacher, textbook writer, nurturer of talent and canny administrator. But Honest Jim also made known his contempt for mediocre faculty and administrators, and he lost a key battle in trying to get Harvard to fund tumor virus studies-the Next Big Thing in the '60s and '70s. Around that time, Jim, ever the nerd, finally met and won the lovely Liz, a Radcliffe undergraduate who married the 39-year-old bachelor in 1968. The chronicle ends abruptly in the mid-'70s, save for a shocker of an epilogue 30 years later. Watson againconfronts Harvard with the need to beef up basic science only to face Larry Summers and later Derek Bok, who had distinctly other ideas-though Watson does not fault Summers for his conjecture on women in science. Vintage Watson: brash, bumptious, brilliant-and never boring.\ \