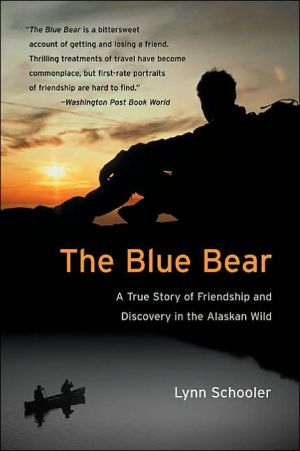

Blue Bear: A True Story of Friendship and Discovery in the Alaskan Wild

With a body twisted by adolescent scoliosis and memories of the brutal death of a woman he loved, Lynn Schooler kept the world at arm's length, drifting through the wilds of Alaska as a commercial fisherman, outdoorsman, and wilderness guide. In 1990, Schooler met Japanese photographer Michio Hoshino, and began a profound friendship cemented by a shared love of adventure and a passionate quest to find the elusive glacier bear, an exceedingly rare creature, seldom seen and shrouded in legend....

Search in google:

"The strength of this beautifully crafted memoir lies in its evocation of the overpowering Alaskan landscape and the thoughts it imposes on the author's agile and receptive mind The New Yorker Schooler, who has worked for many years as a guide in the unpredictable waters of the Alaska Panhandle, has distilled a life of unusual intensity into his first book. The story centers on the renowned nature photographer Michio Hoshino, a client who became a friend, and the two men's ongoing search for the elusive glacier bear, a blue variant of the North American black bear. (Hoshino was killed by a grizzly in Russia, in 1996.) In telling that story, the author wanders, like a good conversationalist, into absorbing asides -- about harrowing episodes in his own past, about the natural history of Alaska, about hardy fellow-eccentrics he has known. As a writer, Schooler is an amateur in the original sense of the word; his writing reveals an abundance of wilderness savvy, and a mind scrupulous about getting the world down as accurately as possible.

Chapter One\ \ \ Severance\ \ \ I was born in 1954 on the edge of the Llano Estacado in West Texas, a desert so vast and featureless that the early Spanish explorers drove a line of stakes across this land to avoid losing their way. The German, Dutch, and Russian immigrants who scattered across West Texas at the turn of the century stringing barbed wire and sinking windmills in an effort to subdue the sunbaked land were a generally mule-headed people, averse to quitting anything once begun, but by the time my father was a young man things were changing, and he became the first of our line to leave our ancestral home'a small, flinty ranch nestled into the mesquite-covered hills near Robert Lee, Texas, where his own father and grandfather had been repeatedly ground down and bested by unending droughts and tightfisted cattle buyers. When I was born he took to the road as a modern-day drummer, driving a blue Plymouth Fury a thousand miles a week across Texas and New Mexico to peddle electrical supplies and hardware to the steadily declining oil and construction industries.\ One afternoon in 1969 (my fifteenth year), Dad's Plymouth rolled into the sunburned yard in a cloud of biting alkali dust. The driver's-side door swung open as the car skidded to a halt and one booted foot swung to the ground. My father cocked his slender frame on the seat, draped an arm over the steering wheel, then sat there looking at me for a moment before waving me over.\ “Look at this,” he said, unfurling a newspaper in my face. “What do you think of that?”\ Dad ran a handthrough his thinning hair while I studied the paper.\ “Well, what do you think?” He was smiling. “They've found oil in Alaska. Lots and lots of oil.”\ I wasn't sure where Alaska was, but it was pretty far away, I knew that. It was much farther than El Paso or even Colorado, where my friend Jimmy went elk hunting with his father. Jimmy was gone for a week when he went to Colorado. If they had oil in Alaska, it probably meant Dad would be gone much longer.\ “You gonna be gone some more?”\ Dad smacked me on the shoulder with the paper, a small web of smile lines crinkling in the corners of his eyes.\ “Well, I guess I might,” he said, starting toward the house. He seemed in a hurry, didn't even close the door to the car. I could smell the Camel cigarettes he smoked lingering in the interior.\ “Will you?” I hollered after him. “Be gone a bunch more?”\ “Don't worry, son.” He was already to the open garage, disappearing into the cool darkness, taking the shortcut into the kitchen. “You're coming with me.”I squinted into the glare of the sun as I looked around at our home -- an acre and a half of hard-packed Texas dirt with a cinderblock house set square in the middle of it; an oil refinery a half mile away that flared off so much waste gas at night that its burning made it possible to read without turning on a lamp; the scrubbed, level horizon of mesquite brush and caliche dirt, the fan of a windmill in the distance. When I spoke it was to myself and out loud.\ “Sounds pretty good to me.” Anyplace, I thought, was probably better than this.\ Dad traded and wheedled, made a deal with a busted wildcat driller for a thirdhand, two-ton Chevrolet oil field truck, then got busy converting it into a makeshift moving van. Barrel-sized saddle tanks straddled the cab left and right.\ “Fuel's expensive, especially in Canada,” Dad said, unscrewing the pipe cap that covered the fill spout and peering into the hollow darkness of one tank. “These'll give us plenty of range. It's a long damn road to Alaska.”\ A swiveling crane the previous owner had made of steel pipe welded into the shape of an A-frame and mounted above the bed to lift welding machines, drill heads, and other heavy objects crashed to the ground as the pins were knocked free. A skeleton of wooden slats went up in its place to support a skin of aluminum in the shape of a box, and Dad showed me how to cut and slide Styrofoam sheets between the boards as insulation. “We might have to live in here,” he said, and I wondered if he was joking. Taking off for Alaska was such a wild idea that living in the back of a truck didn't seem so far-fetched.\ Mother watched with her arms crossed, shaking her head and smiling, then went back to packing. Her best friend dropped off a tub of peanut butter the size of a bucket, and then Jimmy's mother phoned to ask where we were going to get vegetables once we were living in Alaska. My parents put their arms around each other and laughed at that, but Mother's mouth tightened up when she thought no one was looking.\ Everything we owned was carefully wedged, packed, and padded into the back of the big truck and the door bolted shut. My eyes dazzled and danced from the sparkling blue glare of the welder a friend of my father used to build a tow bar onto the front of our old Ford pickup. With the pickup in tow behind the moving van, Dad drove carefully, double-clutching the overloaded rig up the long, slow rises, and I sat beside him, absorbed in a stack of magazines (Argosy, Outdoor Life, True Tales of the Old West) to spare myself the incessant boredom of the plains. My mother and two sisters crept along behind in the family car, playing Otis Redding's “(Sittin' on) The Dock of the Bay” (the only music they could agree on) over and over on the eight-track tape...\ The Blue Bear. Copyright © by Lynn Schooler. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. Available now wherever books are sold.

Author's NoteixAcknowledgmentsxiPrologue11Severance112First Encounters203Eruption384Refugia695Russell Fjord886Johnstone Bay1027Malaspina and Disenchantment Bay1098Tsunami1239The Butcher, the Baker14110The Place Without Storms16011South to Cape Fanshaw18012Storm18913Transients19514Miraculous Fledglings and Shape-Shifting Bears20715Wildfire22216Kamchatka23217Primary Colors246Epilogue263Select Bibliography271

\ From Barnes & NobleThe Barnes & Noble Review\ Lynn Schooler lives on a small boat in Alaska and makes his living safely guiding photographers, nature enthusiasts, and scientists through storm-prone waterways strewn with icebergs, across precarious, unstable fjords and dense northern forests. A loner partly by nature, partly by habit, Schooler becomes lost in mourning after a string of devastating events, his emotional isolation suddenly running parallel to that of his lifestyle. \ The Blue Bear is Schooler's homage to Michio Hoshino, a Japanese photographer whose friendship helped Schooler reemerge from his self-imposed isolation. The outlining story is that of a wilderness guide and a photographer who endeavor to find the elusive glacial bear, often referred to as the Blue Bear because of the metallic sheen of its silvery fur. But this is merely a plot point for a greater allegory that disentangles the tendrils of human relations and illuminates the wondrous natural cycle of ebb and flow, death and rebirth.\ Hoshino teaches Schooler by example, and both his life and his tragic death hold the bittersweet but invaluable lesson that reaffirms Schooler's belief in the interdependence of all things. Schooler is a philosopher with a poetic bent, one capable of elucidating the inexorable bonds between man and nature in a gentle, unfettered prose. As he ruminates over the loss of his dear friend, Schooler recounts, "I am diminished by the sight of the glacier and all it had accomplished -- carving mountains and valleys with its comings and goings, rearranging entire worlds made of stone.... And feeling this, I felt a great contentment warm my blood." Reading The Blue Bear, you will also share in that warmth. (Ann Kashickey)\ \ \ \ \ \ Oregonian"Set amid the awe-inspiring beauty of Alaska’s Glacier Coast, The Blue Bear is a graceful book...."\ \ \ Seattle Times"[Schooler’s] prose is pure cinematography, with Alaska made a character in the story."\ \ \ \ \ New York Times Book Review"The Blue Bear is sublime. [Schooler] threads us into the intimacy of Alaska’s nature."\ \ \ \ \ The New YorkerSchooler, who has worked for many years as a guide in the unpredictable waters of the Alaska Panhandle, has distilled a life of unusual intensity into his first book. The story centers on the renowned nature photographer Michio Hoshino, a client who became a friend, and the two men's ongoing search for the elusive glacier bear, a blue variant of the North American black bear. (Hoshino was killed by a grizzly in Russia, in 1996.) In telling that story, the author wanders, like a good conversationalist, into absorbing asides -- about harrowing episodes in his own past, about the natural history of Alaska, about hardy fellow-eccentrics he has known. As a writer, Schooler is an amateur in the original sense of the word; his writing reveals an abundance of wilderness savvy, and a mind scrupulous about getting the world down as accurately as possible.\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThe strength of this beautifully crafted memoir lies in its evocation of the overpowering Alaskan landscape and the thoughts it imposes on the author's agile and receptive mind, gradually opening his solitary heart to the grace of true friendship. As photographer and writer Schooler recounts, it's been his lifelong tendency to turn inward, ever since his "grandmother's hunchback gene put its weight on my shoulder... trying to hold me down even as my body grew taller." At 16, he fought his scoliosis by strapping on a steel body brace that extended from his chin to his hips, isolating him from other kids. It was a distance he chose to maintain when, two years later, he exchanged his brace for a backpack and departed for the lonely freedom of the countryside around his Alaskan home. Readers meet him as a middle-aged wilderness guide based in Juneau, emotionally battered by the brutal death of a woman he loved, yet still subsumed by the endlessly unfolding drama of wind, weather, predators and prey along the glaciered coast. On an auspicious chartered trip, Schooler leads renowned nature photographer Michio Hoshino to a circle of humpback whales that explode to the surface of a sun-flecked sea with brimming mouthfuls of herring. The Japanese man's simple questions and exquisite sensitivity to the natural world and to his guide slowly draw Schooler out. Over the next decade, the men's bond deepens as they decide to pursue the rare and elusive glacier, or "blue," bear in an archetypal journey whose meaning becomes apparent only after Schooler has suffered the loss of his friend. 8 pages of color photos. (May) Forecast: More ruminative and profound than its hair-raising subtitle might suggest, this memoir ranks with the best nature writing and deserves commensurate review attention. Foreign rights have been sold in 13 countries. Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library Journalinstead. Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ School Library JournalAdult/High School-A memoir by a wilderness guide along Alaska's glacier coast. It includes tragedy and heartache almost beyond measure, but also profound beauty, deep friendship, and enormous respect for the world we inhabit. Schooler's friendship with the acclaimed Japanese photographer Michio Hoshino and their search for the highly elusive blue bear (aka glacier bear) is the central story. The author's portrait of this thoughtful, engaging man evolves slowly and is thoroughly convincing. Another story concerns the brutal death of a woman the author loved at the hands of a monstrous mass murderer. That this killer and Hoshino could live on the same planet and be of the same species is just one of the many wonders of nature that appear in Schooler's excellent book. His sincerity, honesty, and humbleness are palpable, and there are lessons here for readers of any age.-Robert Saunderson, Berkeley Public Library, CA Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ From The CriticsPhotographer and wildlife guide Schooler recounts the story of his friendship with Japanese photographer Michio Hoshino, their trips into the Alaskan wilderness in search of the rare glacier bear, Hoshino's death by mauling, and the lessons that Schooler drew from Hoshino's life and death. Annotation c. Book News, Inc., Portland, OR (booknews.com)\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsVital travels along the wild Alaskan coast, punctuated by dreadful circumstances that rob wildlife photographer and guide Schooler of the people he loves. Having spent an important period of his youth in a brace for scoliosis, he writes, "My strangeness had isolated me from my fellow teens, and I was to find that my isolation was permanent, my hermitage ongoing." When Schooler's family moved to Alaska, the land captivated him: "I loved it fiercely for its power of recovery after being scalped down to bedrock by ice or violent tsunamis... I loved it the way a dog loves to ride in the back of a pickup." Which is good, because in the course of this memoir, he will lose a woman friend to a serial killer, his father to cancer, and a longstanding friend to a bear attack. These elements thread their way through the narrative, keeping the overall mood somber and deepening the shadows, but the principal storyline retraces Schooler's forays afield with the Japanese photographer, Michio Hoshino. Their relationship is mutually advantageous at first; Schooler is a wilderness guide intimately familiar with the southern Alaskan coast, and Hoshino is generous with his knowledge of photography. It blossoms into friendship as the two work together to capture images of Alaska and pursue an encounter with the elusive blue bear that lives on the 500-mile stretch of coast between Prince William Sound and Ketchikan. Alaska is made for adventure, and the two men have plenty, though Schooler is sharp enough to keep drama pressurized but under a lid. He also zests the work with plenty of tidbits, such as the role of the isotope cycle in nature and why glaciers are blue. An emotionally punishing memoir that findsbeauty in the frailty of life and impermanence against a grand setting. Author tour\ \