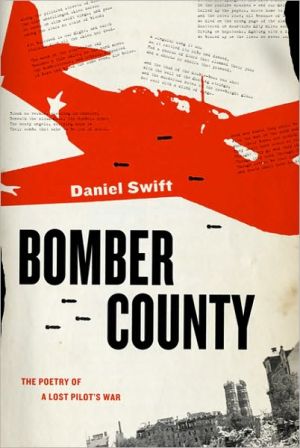

Bomber County: The Poetry of a Lost Pilot's War

In early June 1943, James Eric Swift, a pilot with the 83rd Squadron of the Royal Air Force, boarded his Lancaster bomber for a night raid on Münster and disappeared. Widespread aerial bombardment was to the Second World War what the trenches were to the First: a shocking and new form of warfare, wretched and unexpected, and carried out at a terrible scale of loss. Just as the trenches produced the most remarkable poetry of the First World War, so too did the bombing campaigns foster a...

Search in google:

In early June 1943, James Eric Swift, a pilot with the 83rd Squadron of the Royal Air Force, boarded his Lancaster bomber for a night raid on Münster and disappeared.Widespread aerial bombardment was to the Second World War what the trenches were to the First: a shocking and new form of warfare, wretched and unexpected, and carried out at a terrible scale of loss. Just as the trenches produced the most remarkable poetry of the First World War, so too did the bombing campaigns foster a haunting set of poems during the Second.In researching the life of his grandfather, Daniel Swift became engrossed with the connections between air war and poetry. Ostensibly a narrative of the author’s search for his lost grandfather through military and civilian archives and in interviews conducted in the Netherlands, Germany, and England, Bomber County is also an examination of the relationship between the bombing campaigns of World War II and poetry, an investigation into the experience of bombing and being bombed, and a powerful reckoning with the morals and literature of a vanished moment.The Barnes & Noble ReviewIn saying of this beautiful and profound book that booksellers will be hard pressed to know where to shelve it, I pay it a double compliment: for it is one of those rare works which defies categorization, being a tapestry of several interwoven genres at once: a memoir, a history, an understated epic, a book about poetry and war, a personal journey, and a poignant search for a tragic truth. It ranges so widely in its references, and focuses so acutely in its vision, that it moves and impresses not only because of the sadness of the central story, but also because of the sheer scope of the meanings that the author collects around it.

Bomber County\ Chapter 1. Five Minutes after the Air Raid\ 12 June 1943\ \ After the air raid, Virginia Woolf went for a walk. 'The greatest pleasure of town life in winter - rambling the streets of London,' she had written, a decade before. She called it 'street haunting', and in the essay of that title she gives instructions on how this should be done. 'The hour should be the evening and the season winter, for in winter the champagne brightness of the air and the sociability of the streets are grateful,' she wrote: 'The evening hour, too, gives us the irresponsibility which darkness and lamplight bestow. We are no longer quite ourselves.' Picture her, then, stepping out into the bombed city. It is perhaps a little earlier in the day than she might have liked, this afternoon in the middle of January 1941, and in less than three months she will be dead, but today she is here to take a quiet pleasure in the ruins.\ 'I went to London Bridge,' she notes in her diary:\ I looked at the river; very misty; some tufts of smoke, perhaps from burning houses. There was another fire on Saturday. Then I saw a cliff of wall, eaten out, at one corner; a great corner all smashed; a Bank; the Monument erect; tried to get a Bus; but such a block I dismounted; & the second Bus advised me to walk. A complete jam of traffic; for streets were being blown up. So by tube to the Temple; & there wandered in the desolate ruins of my old squares; gashed; dismantled; the old red bricks all white powder, something like a builders yard. Grey dirt & broken windows; sightseers; all that completeness ravished & demolished.\ She is watching carefully, making her way north and then west, through traffic jams and rubble, and she pauses for a while in 'my old squares', the wide and orderly spaces of Bloomsbury where she used to live. But then, quite simply, life interrupts: 'So to Buzsards where, for almost the first time, I decided to eat gluttonously. Turkey &pancakes. How rich, how solid. 4/- they cost. And so to the L.L. where I collected specimens of Eng. litre [English literature].' From Bloomsbury, she walked past the Air Ministry on Oxford Street on her way to Buzsards, a café known for its wedding cakes and before the war its tables out on the street. After lunch, she goes on to the London Library in St James's Square. The fastest route is straight down Regent Street, and she had work to do on a new book.\ Woolf's diaries, as the war begins, tell of a growing fascination. On the Sunday that Britain declared war, she was sewing black-out curtains at Monk's House, the cottage in Sussex she shared with her husband Leonard, and she wrote: 'I suppose the bombs are falling on rooms like this in Warsaw.' Three days later: 'Our first air raid at 8.30 this morning. A warbling that gradually insinuates itself as I lay in bed. So dressed & walked on the terrace with L. Sky clear. All cottages shut. All clear.' The bombs did not come that morning, but she waits and she watches. 'No raids yet,' she recorded on Monday, 11 September, but saw 'Over London a light spotted veil' of the silver barrage balloons on steel ropes, to defend the city from low-flying planes. The winter comes, and then the spring; a German bomber flies over Monk's House; Holland falls, and Belgium, and Chamberlain resigns. She is always looking at the skies. 'The bomb terror,' she writes in her diary: 'Going to London to be bombed.' In May 1940 there are rumours of invasion, and at the end of the month: 'A great thunderstorm. I was walking on the marsh & thought it was the guns on the channel ports. Then, as they swerved, I conceived a raid on London; turned on the wireless; heard some prattler; & then the guns began to lighten.' Transformed by her poised imagination, the rain becomes a raid, and then the falling bombs return to rain. 'I conceived a raid,' writes Virginia Woolf, the great novelist, thinking bombers where there were none.\ Of course, in these fixated times she was at work on a novel. She called it 'Poyntz Hall' but it was published after her death as Between the Acts, and it too imagines bombers. After the country-house pageant which is the centre of the novel, the Reverend Streatfieldstands on a soap box to address the audience on the subject of funds for 'the illumination of our dear old church', and as he begins to speak:\ Mr Streatfield paused. He listened. Did he hear some distant music?\ He continued: 'But there is still a deficit' (he consulted his paper) 'of one hundred and seventy-five pounds odd. So that each of us who has enjoyed this pageant has still an opp ...' The word was cut in two. A zoom severed it. Twelve aeroplanes in perfect formation like a flight of wild duck came overhead. That was the music. The audience gaped; the audience gazed. The zoom became drone. The planes had passed.\ ' ... portunity,' Mr Streatfield continued, 'to make a contribution.'\ The duck-like passing planes gently, ironically interrupt the platitudes of village life, but they are not wholly fictional. Throughout the spring and summer of 1940, Woolf had been watching the fighters scrambling over the downs, to the Battle of Britain, and hearing the distant music as the bombers came and went. Some days that summer, her diary is little more than a war report: 'Nightly raids on the east & south coast. 6, 3, 12 people killed nightly.' And even on the nights when there are no bombers - 'Listened for another; none came' - she begins to imagine them, to transform them into something useful. On the last Thursday of May 1940 she went out for a walk and 'Instantly wild duck flights of aeroplanes came over head; manoeuvred; took up positions & passed over.'\ So much of Woolf's diaries reads as the roughs for so much of her published writing, and the notes on bombing from 1940 find their way into an essay, 'Thoughts on Peace in an Air Raid'. She wrote it in August for an American symposium on women in the war and here she returns to the moment when the bombers are above. As she narrates: 'The sound of sawing overhead has increased. All the searchlights are erect. They point at a spot exactly above this roof. At any moment a bomb may fall on this very room. One, two,three, four, five, six ... the seconds pass.' Here we are, waiting and watching, as so often she was, and this time, as always before, the bombs do not fall, and she goes on:\ But during those seconds of suspense all thinking stopped. All feeling, save one dull dread, ceased. A nail fixed the whole being to one hard board. The emotion of fear and of hate is therefore sterile, unfertile. Directly that fear passes, the mind reaches out and instinctively revives itself by trying to create. Since the room is dark it can only create from memory. It reaches out to the memory of other Augusts - in Bayreuth, listening to Wagner; in Rome, walking over the Campagna; in London. Friends' voices come back. Scraps of poetry return.\ In the moments after the air raid, the frozen imagination - nailed to one hard board - awakes again, and it does so by remembering, and creating; by making something new from fragments of the past, a memory of music, a line of poetry.\ In the last week of August 1940, the weather was hot, and every day in Woolf's diary there are air raid warnings. On the afternoon of Saturday, 7 September, the Blitz begins, and two days later she and Leonard go to London. 'Left the car & saw Holborn,' she writes:\ A vast gap at the top of Chancery Lane. Smoking still. Some great shop entirely destroyed: the hotel opposite like a shell. In a wine shop there were no windows left. People standing at the tables - I think drink being served. Heaps of blue green glass in the road at Chancery Lane. Men breaking off fragments left in the frames.\ The bombs continue to fall on the city. In the middle of October, she and Leonard return to London once more. They pass their old flat, in Tavistock Square, now open to the sky —'I cd just see a piece of my studio wall standing: otherwise rubble where I wrote somany books,' she notes - and go on to their apartment at Mecklenburgh Square. Here, the windows had been blown out by a near bomb - 'All again litter, glass, black soft dust, plaster powder' - and they retrieve a few of their possessions. Some diaries and notebooks; 'Darwin, & the Silver, & some glass & china'; her fur coat, now dusty: at half past two they climb back into their little car and drive out to Sussex. She had long been ready to leave the city. In September, she had written to her old friend Ethyl Smith: 'When I see a great smash like a crushed match box where an old house stood I wave my hand to London.' Now, 'Exhilaration at losing possessions', she writes, and 'I shd like to start life, in peace, almost bare - free to go anywhere.'\ Virginia Woolf was haunted by air raids, and after she killed herself at the end of March 1941, some were quick to blame the bombers. Violet Dickinson wrote to Virginia's sister Vanessa: 'I think she was dreadfully bothered by the noise and aeroplanes and headaches', and Malcolm Cowley, reviewing the posthumously published Between the Acts in the New Republic, called her 'a war casualty'. The raids for her were a dark fascination, and in a long diary entry written on Wednesday, 2 October 1940, she is sitting at Monk's House watching the sunset and thinking of her death in an air raid. 'Oh I try to imagine how one's killed by a bomb,' she writes, and furnishes the scene:\ I've got it fairly vivid - the sensation: but cant see anything but suffocating nonentity following after. I shall think - oh I wanted another 10 years - not this - & shant, for once, be able to describe it. It - I mean death; no, the scrunching & scrambling, the crushing of my bone shade in on my very active eye & brain: the process of putting out the light, - painful? Yes. Terrifying. I suppose so - Then a swoon; a drum; two or three gulps attempting consciousness - & then, dot dot dot\ Yet there is no full stop, and if there is a death-wish here it is overwhelmed by an opposite desire: to imagine the moment and to tellwhat comes after the air raid. She calls it 'the process of putting out the light', the last moments of consciousness, but she is not quite willing to let go of her deep literariness, for she is quoting Othello's words before he strangles Desdemona. 'Put out the light,' he curses her, and 'then put out the light.' It is a scene impossible to render, but 'I've got it fairly vivid': here is a trace of writerly pride.\ After the air raid, a scrap of poetry returns, and a memory of August in Rome. There are sightseers in the rubble, picking at the fragments of blue green glass, and perhaps a taste of wine from the blown-out wine shop. Later in the afternoon, perhaps, a plate of turkey and pancakes at a café on Oxford Street.\ This is not to say that the things we recover from the ruins are easy, or even necessarily good for us. On the day of her death, Virginia Woolf walked out to the river that runs near her house in Sussex and collected a stone from the bank. Putting the stone into the pocket of the fur coat she had retrieved from the flat at Mecklenburgh Square five months earlier, she drowned herself.\ But it is to say that we do not only find death in the ruins. That day in Mecklenburgh Square Woolf took her books and china too, and the stationer's ring-bound journal in which she wrote her final diary entries. In the last months of her life, Woolf was planning an ambitious new book, a study that was to be about all of literature and all of her reading.\ This was her grandest bid to bring something back from the ruins. She was not reading despite the bombs; she was reading with them, and the two - reading and bombs - are jumbled together in one of her last letters. 'Did I tell you I'm reading the whole of English literature through?' she wrote to Ethyl Smith on 1 February 1941:\ By the time I've reached Shakespeare the bombs will be falling. So I've arranged a very nice last scene: reading Shakespeare, having forgotten my gas mask, I shall fade far away, and quite forget ... They brought down a raider the other side of Lewes yesterday. I wascycling in to get our butter, but only heard a drone in the clouds. Thank God, as you would say, one's fathers left one a taste for reading! Instead of thinking, by May we shall be - whatever it may be: I think, only 3 months to read Ben Jonson, Milton, Donne and all the rest!\ She called this last book 'Turning the Page' or 'Reading at Random', and according to her biographer Hermione Lee it was planned as 'a collection of essays which would make up a version of English literary history'. She only completed fragments of the first two chapters.\ What survives the air raid? The imagination, and then the scrunching and scrambling as the mind seeks to re-create itself. Hermione Lee records an anecdote told by Somerset Maugham that reveals much of Woolf's appreciation of bombing. After a dinner party in Westminster,' he recalled, 'she insisted on walking home alone during an air-raid. Anxious for her safety, he followed her, and saw her, lit up by the flashes of gun-fire, standing in the road and raising her arms to the sky.' She is beckoning to them, come closer.\ \ In my childhood, I had only one grandfather. One was there, although already dead by the time I knew what that might mean. Grandparents are myths: their lives are the stories they suggest and we are told, and the one I had was myth enough to make up for the lopsided genealogy. He was Australian, a writer who left suburban Melbourne in the hot slow years before the Second World War to become a war correspondent in Europe, and he built a big house on the side of a hill in Tuscany, planted eucalyptus trees, entertained with a servant in a white jacket. There is a photograph of him having lunch with Hemingway. He was my mother's father, and my young cousins and I spent every school holiday in that house, playing badminton and lighting fires and never learning to speak Italian. This was my grandfather; I grew up in this myth.\ But everyone has two grandfathers. I had another. My father'sfather simply wasn't there, and my father never spoke of him. He was not there and when I started writing this book, I did not know his first name.\ My father and I are in his car, driving to an airport, and I have at last asked about the day his father died: about 12 June 1943. I don't remember what it was, but I do remember a catastrophe, my father says, and it must have been bad because that night he was allowed to sleep in his mother's bed. My father was three years old. At six, he was sent to boarding school. This felt like punishment. Later, he wanted someone to tell him what had happened, but he did not ask. You do not talk about this. Maybe everyone has this, says my father, this unease about where I was from. Maybe it is a standard emotion.\ Later, my father sends me something he has written. It might be useful, he says, and I open it:\ Aged five or six, just after the war and I think for several years after, I had a favourite bedtime story. I made my mother read it every night for months. In the story, a Russian family, mother and two children, are driving home at night in a pony-drawn sleigh through the forest in the snow, under the bright stars. As they near home they hear a pack of wolves behind. They hurry, but the wolves are faster. The family is crossing a clearing in the forest when the wolves catch up with them, leaping and snarling at the sleigh. At the moment all is lost, a dark figure steps silently from the surrounding forest, raises his gun and shoots the wolves. It is the children's father.\ A few years later, he was at school, and learning the Lord's Prayer. 'Our father, which art in heaven,' it begins, and he imagined this was his father. He survived school, and then university, and in the autumn of 1962 he moved to France. 'Having always vaguely imagined as a child that my father might have survived the war - shot down and memory lost - this idea firmly rooted itself in my mind when I moved to France,' he writes: 'I had fantasies about theday I would meet him and recognise him. Sometimes he recognised me, and stopped me in the street. Quite soon further layers added themselves: he was not only alive, but very rich.' In time, my father marries, and has children, and one day as a small boy I am doing a project on ghosts for my homework. I don't remember when, but I asked my grandmother about ghosts and she said, of course. We were in her house, a thatched cottage in Sussex, and she pointed to the tree in the curve of the drive. A long time ago, she had seen my grandfather sitting there, and she was delighted, because she was not expecting him to have returned yet from the base. It was the day he died.\ After the air raid, in the place of ceremonies, there are only stories. On 12 June 1943, the Wing Commander of 83 Squadron at RAF Wyton wrote to my grandmother. Such letters have a genre, a work they now must do, and he begins: 'I am writing to express my sympathy and that of my Squadron over the news that your husband is missing from an operational flight. He was Captain of an aircraft detailed to attack Münster on the night of 11/12 June, and after leaving base nothing more was heard.' Nothing more, that is, until now, for Wing Commander Searby is not only consoling. He is starting to raise a fiction. He continues: 'It is to be hoped that we shall have further news of them as it is possible that they may have been able to bale out or force land in enemy territory', and I have read of this before: a forced landing at night; an injury perhaps; far from home. And then a journey, trials, alliances, the occasional kindness of strangers. A night in a haybarn. A borrowed tweed coat. The letter struggles between finality - the past tense, nothing more was heard - and the fantasy of continuation. 'This is indeed a great loss to the Squadron,' Searby writes, for 'He had altogether carried out 38 sorties and his experience was a valuable asset to the Squadron at this stage of the war.' When I later read his logbook, I count thirty-nine. Münster was his thirty-ninth raid, and his thirty-ninth raid is not yet complete. He is not yet back from bombing Münster.\ I would like to tell you, here, about a death, but as I sit readingthese documents sixty-five years later, I find I can't do anything quite that simple. On 5 January 1944, there was another letter: this time to my great-grandparents, and from the Air Ministry Casualty Branch, on Oxford Street in London. 'I am directed to inform you with regret,' it begins, and then sets out another fiction: 'in view of the lapse of time and the absence of any further news regarding your son, Acting Squadron Leader J. E. Swift, D.F.C., since he was reported missing, action has been taken to presume, for official purposes, that he lost his life on 12th June 1943.' In the absence of a corpse, he leaves a corpse-shaped space and some trouble for others to finish. The Wing Commander imagined him alive, and the Casualty Branch presumed him dead, and only later, eight months after he was lost, came another letter. 'Recovered from the shore at Callantsoog, Holland, on the 17th June, 1943,' it says at last, 'the body.'\ After the air raid, Virginia Woolf walks the city. She kneels to collect a dusty fur coat, and elsewhere in the ruins someone is pushing the shards of blue green glass, clean against his finger. After the air raid, Wing Commander Searby writes a letter, and my grandmother smiles at a ghost. There are fictions which cluster in the moment of trauma, but after the air raid one particular kind of literary imagining is richest of all. Virginia Woolf was not a poet, but after the air raid, she wrote, scraps of poetry return to us, and when she thought of being bombed she thought too of reading the great poets, of Shakespeare, Donne and Milton.\ Here is our first missing: an absence of poetry. They said, and they say still to this day, that there was no poetry for this war. On New Year's Eve of 1939, four months into a war that would last five years, the Times Literary Supplement called on the poets of England to join the battle. The TLS was and still is the most influential literary journal in England, and addressed its editorial 'To the Poets of 1940'. 'What can the poets do with the year 1940, when the world seems to be threatened with a new dark age?' begins the editorial, and ends by insisting: 'The monstrous threat to belief and freedom which we are fighting should urge new psalmists to fresh songs of deliverance.'\ They were soon disappointed. By November 1940, the same editors declared that 'the creative imagination to-day is, not nonexistent, but put on the shelf for the duration', and in the Christmas round-up of 1940 books they return to the theme, explaining: 'It is probably true that war has inspired little poetry of lasting value except in retrospect, that the imagination can only grasp its deeper meaning when the torrent of sensational violence has swept by.' This torrent of sensational violence was the Blitz, as London had been bombed each night during the autumn and winter of 1940, and in their first issues of 1941 they note the burning of Stationer's Hall and Paternoster Row, 'the old bookselling quarter' of London. No fragile papery thing such as poetry could survive the flames, and the literal fires of London - three million books burned in one warehouse in one night - were reflected by the poets themselves. In late 1941, Stevie Smith wrote a poem which elegantly refuses its own subject. Called 'The Poets are Silent', it is only four lines long:\ There's no new spirit abroad, As I looked, I saw: And I say that it is to the poet's merit To be silent about the war.\ Cecil Day Lewis agreed. 'It is the logic of our times, / No subject for immortal verse,' he wrote, in a short poem called 'Where are the War Poets?', and when in late 1942 T. S. Eliot was invited to contribute to an American book on the destruction of London, he was hardly more enthusiastic. 'It seems just possible that a poem might happen / To a very young man,' he started, and then snapped shut even this most tentative suggestion. 'But a poem is not poetry - / That is a life,' he concludes, and 'war is not a life: it is a situation'.\ The poets in London did not simply turn away: they felt the need to explain, and to give a theory to the absence. They began to tell a story about the war, about how it was ignoble and somehow did not deserve their poetry. In October 1941, Robert Graves —famous forhis bestselling memoir of service in the First World War, Good-Bye to All That —gave a radio talk on the question of 'Why has this war produced no war poets?', and explained that the answer lay with the difference between the two wars. During the first, 'Poems about the horrors of the trenches were originally written to stir the ignorant and complacent people at home', but now, he insisted, nobody has any doubts 'about the justice of the British cause or about the necessity of the war's continuance'. If there is no injustice, there is no need for poets 'to draw attention to the evils of war'. This war is a duty, and the soldier a policeman on the beat. It lacks drama, and in its practice is a messy thing, part of a disappointing age. 'It should be added that no war poetry can be expected from the Royal Air Force,' he continues, as 'The internal combustion engine does not seem to consort with poetry.'\ We see here the thickening of a theme, as patterns of thinking harden into assumptions and as poetry is pushed from the war. 'Where are the poets of this war?' begins the TLS editorial of 8 August 1942: 'This question is often asked by those who remember that the last war threw up a fair amount of notable poetry.' A couple of pages on in this same issue is a review of a new book that might apparently settle the editorial question: called Poems of This War by Younger Poets, the volume collects exactly what the title promises, some slim sentimental verses by soldiers, young men fighting. But again, we are told to look elsewhere. 'The tone and temper of the poetry so far published during this war are inevitably distinct from that of a quarter of a century ago,' insists the anonymous reviewer, and goes on to refuse even to name the poets collected in this anthology. 'In a short review it is impossible to pick out any of the thirty-six contributors for special notice,' the review waspishly ends: 'Nor does the anthology tempt us to do so.'\ No war poets: the chant goes up. No Wilfred Owen, no Siegfried Sassoon, no Rupert Brooke: again and again, the trinity of Great War poets is invoked to condemn the failings of this moment in verse. By 1945 the claim had stuck, safe enough now to be droppedin passing. 'The last war has had neither its Iliad nor its War and Peace,' wrote George Steiner in The Death of Tragedy (1961). 'None who have dealt with it have matched the control of remembrance achieved by Robert Graves or Sassoon in their accounts of 1914-18,' he concludes, and in the bibliography to his influential textbook English History 1914-1945 (1970) the historian A. J. P. Taylor notes: 'Works of literature are fewer and less enlightening about the second world war than about the first.' Close to the end of his 1975 study The Great War and Modern Memory the literary historian Paul Fussell describes the 'conventionality' of Second World War poetry, part of a larger process of young writers 'eschewing the Second War as a source of myth and instead jumping back to its predecessor'. In turn, writing in the New Statesman in 1978, Peter Conrad argued that 'This was a war to which literature conscientiously objected', and when in 1989 Paul Fussell came to write a study of the psychology of the Second World War he dismissed in a single sentence the possibility of poetry. 'It was a savage, insensate affair, barely conceivable to the well-conducted imagination,' he insisted, and then added, in parentheses: '(the main reason there's so little good writing about it)'. 'It is true,' declares Martin Francis in The Flyer: British Culture and the Royal Air Force, 1939-1945 (2008), 'that the RAF failed to produce an outstanding verse writer during the war', and as claims these have the reassurance of each other.\ On the shelf behind my desk as I write there is a small stack of books: they are anthologies of Second World War poetry. Here in faded maroon, its spine attached by tape, is Poems of This War by Younger Poets (1942), and beside it in more martial grey The New Treasury of War Poetry (1943). The Terrible Rain (1966), edited by Brian Gardner, shows streets and rubble on the cover while Poetry of the Second World War (1995), edited by Desmond Graham, is illustrated with green- and orange-tinted shots of refugees. Most recently and demurely, Poets of World War II (2003), part of the Library of America series, is small and pale green, and carries by the contents page a photograph of its editor, Harvey Shapiro, smiling in a flying suit.\ The fact of anthologies does not still this debate, for these are judgements of value, not of quantity. What is being asked, and what is being denied, is the possibility of testimony: whether poetry can add to the record of this war. The same query troubled the poets themselves. In his anthology The Poetry of War 1939-1945 (1965), Ian Hamilton includes a section of what he calls 'War Poet' poems, and here the claims by the TLS and famous poets find answer in the worries of writers in verse as they seek to define their own place in the chaos. Some are defensive, such as Donald Bain of the Royal Artillery and Gordon Highlanders - in his 'War Poet' he writes: 'We do not wish to moralize, only to ease our dusty throats' - and some are ashamed. Robert Conquest, who served with the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and as an intelligence officer in Bulgaria, begins his 'Poem' of 1944 with an apology. 'No, I cannot write the poem of war,' he admits: 'Neither the colossal dying nor the local scene'.\ They are asking for a role in this; they are considering how to witness. 'I must believe / That somewhere the poet is working who can handle / The flung world and his own heart,' continues Conquest, for the poet now must do both, and must pay particular regard to the jumbled landscape of this war. 'I offer him the debris / Of five years undirected storm in self and Europe,' Conquest concludes, and as he imagines the possible poetry another will write he is also giving instructions on how this may be done. It will be a poetry of debris and storm, of the flung world; a poetry of pieces. 'How to draw altogether to a purity / To a rarity?' asks Richard Eberhart in 'War and Poetry'. He spent the war with the US Naval Reserve, teaching air gunners to shoot .50 calibre Browning machine guns from planes, and answers with advice: 'The poem should be the things we lost'.\ The war poets debate is a footnote to the history of the Second World War, but it is mirrored in a second tradition of silence: the forgetting of the bombers. For in the place of a full record of bombing, there is also a curious absence. In the autumn of 1997, thememoirist and novelist W G. Sebald gave a series of lectures on the subject of air raids and German literature; they were published in England as On the Natural History of Destruction (2003). The RAF, he explained, attacked 131 German towns and cities, and destroyed three and a half million homes during their bombing campaigns; they dropped close to a million tons of bombs and yet 'The images of this horrifying chapter of our history have never really crossed the threshold of our national consciousness.' Sebald went on to suggest that 'There was a tacit agreement, equally binding on everyone, that the true state of material and moral ruin in which the country found itself was not to be described', and points particularly to the refusal of writers to break 'the well-kept secret of the corpses built into the foundations of our state'.\ In Britain, too, many turned away. At the House of Commons in London on 12 March 1946, during the first debate on the future of the RAF after the end of the war, Wing Commander Millington, the MP for Chelmsford, rose to speak. He had completed a tour of operations with Bomber Command during the war, and he began: 'We want - that is, the people who served in Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force and their next-of-kin - a categorical assurance that the work we did was militarily and strategically justified.' He then gave a catalogue of the loss. 'When I first reported for operational duty, the average expectation of life for nine crews out of 10, in the group to which I was posted, was less than six months,' he said, and listed 50,000 men in Bomber Command killed and 15,000 serious casualties, of a total of 110,000 trained.\ Millington's speech that day was motivated by what he feared was the beginning of an institutional disregard, 'an undercurrent of thought that the strategic work of Bomber Command was wasteful of our manpower and over-destructive in its effect upon the enemy'. The great firestorms of Hamburg and particularly of Dresden on Valentine's Day of 1945 - when the roads and windows melted in the blaze and tens of thousands of civilians were either burned or suffocated as the flames sucked the oxygen out of the city centre - hadattracted criticism in the English press. That spring, there began to be reports of the damage in Germany: approximately seven million left homeless, and 42.8 cubic metres of rubble in Dresden for every surviving resident. All the reckonings vary greatly, and always will, but somewhere between 300,000 and 600,000 Germans, mostly civilians, had been killed by RAF and USAAF bombs. But what is perhaps most frightening about this scale of destruction is how it has been met with silence. 'In the safety of peace,' writes Max Hastings in his 1979 history of Bomber Command, 'the bombers' part in the war was one that many politicians and civilians would prefer to forget.'\ Perhaps this chill is even worse than simple condemnation. On 13 May 1945, Churchill addressed the nation and announced victory in Europe. He thanked the Royal Navy and the Merchant Marine; he thanked the army, and the fighter pilots, but did not mention Bomber Command. 'When it came to awarding medals,' writes Patrick Bishop in his study Bomber Boys (2007), 'care was taken not to identify the strategic bombing offensive as a distinct campaign.' There is no memorial to Bomber Command in central London. 'You would think the fury of aerial bombardment / Would rouse God to relent,' wrote Richard Eberhart, but:\ the infinite spaces Are still silent. He looks on shock-pried faces. History, even, does not know what is meant.\ All around the bombers falls a kind of quiet.\ \ At the start of the new year, my father and I get back into his car and drive to Gloucestershire to meet the Squadron Leader. Tony Iveson is eighty-nine years old, and before he was a bomber pilot he had flown fighters in the Battle of Britain. He wears a grey jumper, with a logo that says 'Aérospatiale'; it was given to him by a friend who was a test pilot for Concorde. Later in the year, he is planning togive a lecture on courage. I ask him what he is going to talk about. 'You can only talk about your personal experience,' he says.\ The Squadron Leader is now running a campaign for a memorial to the things that he, and others like him, did: to the 55,000 lost - when the bombers talk of the dead, they call them lost - and the ground crews that put the bombers in the air. 'There's a memorial in Park Lane to animals,' he says: 'Come on.' The Bomber Command Association have a polished website for the memorial campaign, and are supported by the Telegraph newspaper, and the publicity materials return often to the same set of claims. 'Bomber Command flew missions on almost every day and night of the war,' they say, and 'It was the only arm of the British forces to continually attack the German homeland throughout the war.'\ This afternoon in Gloucestershire, the Squadron Leader speaks in practised phrases of what the air war meant. 'The bombing offensive prevented attack in our country,' he says. 'For more than four years' - between the retreat from Dunkirk and the Normandy landings - 'you could not leave the country for more than twenty miles in any direction.' For more than four years, that is, the war was a conflict fought in the east between Germany and Russia, and to the south in North Africa. Apart from the bombing campaign, there was no western front. 'If we had lost in 1940,' he says, 'and the Germans had got here, there would be nothing the Americans could have done.'\ What the bombers fear is silence, and what they want is witness. Why is bombing controversial, I ask him. 'Because we killed civilians,' he says. Early in the war it was a waste of time, he tells me: they did a lot of dead reckoning, over a blacked-out Germany, and the truth is that they often did not know what they were bombing. I asked if he was scared. 'It was a long time ago,' he says, and the waiting was the worst part: 'once you got on the job, you were very busy', busy up in the air, and no time to think of what was below. Most of the time, they just wanted to get home. 'You get used to things,' he says.\ The problem was that the bombers got better as the war went on. 'The night of Dresden everything worked perfectly,' he says: 'the weather was right, the marking was right, and 5 Group wrecked the place.' One million tons of bombs was no mistake, and this is the trouble the bombers face when they speak of memorials. 'Bomber Command was a terrible weapon,' he says. The fire hisses, and outside, the watered-down English winter light. From the other room I hear my father say, this grief distorted my childhood.\ Later in the afternoon, the Squadron Leader does a German accent, and tells funny stories he has told before. My father drives me to the local station, and I take the train back to London, and it occurs to me that I have asked this man questions I would scarcely ask of an old friend - I have asked him if he was scared, and if he thought of the civilians he had killed - but I did not ask him what he did after the war. I had not thought he had a life, after the air raids. On the train, I look out of the window, but it is getting dark, and all I can see is my own reflection. The next day, I go to the library.\ \ Because I did not trust this story of decline, I went back to the TLS and read everything else. I avoided the headmistressy editorials and looked instead at the advertising banners, the 'News and Notes' section on the front page, the regular features. Here, in the announcements of minor publishing news from sixty years ago, I found another story of the war and literature, and another way to memorialize the bombers.\ On Saturday, 2 December 1939, 'News and Notes' announced the following: Magna Carta had been moved from Lincoln Cathedral to the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, for the duration of the war; Cornhill magazine was suspending publication; and Gone with the Wind was the most popular novel in Germany. Coverage of the war sneaks into these pages in echoes and allusions, as on page 2, during a brief review of Leonard Woolf's new book, Barbarians at the Gate. 'Things have changed much in 2,500 years,' observes the reviewer, but there is no doubt 'that the civilization we are defendingtoday, with all that it implies in liberty, justice, tolerance, humanity and truth, is at bottom the civilization of Athens'.\ If this were all you knew - if the only historical memory available of the Second World War were a complete set of the wartime TLS - you would see a struggle between forces of light and dark, waged in cultural terms: the civilization of Athens and Magna Carta on one side, faceless barbarians reading Gone with the Wind on the other. But you would see also a war dominated by one particular unknown and terrifying form of fighting. The front cover of the Christmas Supplement of 16 December 1939 ran a complete poem by Dorothy Wellesley, called 'The Enemy', which is at the same time a bloodthirsty ode to aerial bombing and a baroque nightmare of this terrible technology. 'There is some delight in bombing an Enemy / Whom all mankind must hate,' it begins, and rouses itself through fifty leaden lines to a final exclamation:\ Kill off the living, Enemy! For you have raised the dead. They come with clanging sound, and phosphorescent eyes, With the worm that never dies, They rise, they rise, who care no more for pain! Pale Enemy, hail! The nations are bombing the cemeteries of the slain.\ The ghosts of old soldiers, killed in earlier wars, have been woken by the bombs, and they are coming back. This is a horrible poem, with its dodgy rhymes and awkward meter, yet it has a mesmerizing force to it, and establishes a theme to which the TLS will return, apparently unconsciously, again and again: that bombing is a particular threat to civilization, and yet may provoke poetry.\ I read on, into 1940, and while the pressures of war occasionally intrude upon the grey pages - in a mention of a book of wartime recipes, or an essay on the policies of the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain - literary London appears largely unruffled. In Januaryof 1940, as war is spreading across Europe, a note insists that 'no-one who respects the high tradition of literature would willingly let the hundredth birthday of Austin Dobson pass without a tribute of gratitude and reverence.' A couple of weeks later, in a short notice about the closure of libraries in London, the editors report: 'Nothing could be more disastrous to us as a people, or lead more certainly to our downfall, than the impoverishment of our cultural and artistic life.' They hold to this ideal of cultural continuity in the face of war, and the essays continue, on Chaucer, on Irish drama, on the achievement of the seventeenth-century playwright Philip Massinger. Dickens's birthday is duly noted, and there are illustrations of English scenes: of meadows in Somerset, the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford. Every now and then, the war does throw its shadows, and where those fall, they tend to form a pattern. The Spring Books Supplement for 1940 runs on its cover a poem by Edith Sitwell, called 'Lullaby', which begins:\ Though the world has slipped and gone, Sounds my loud discordant cry Like the steel birds' song on high.\ The illustration shows three bombers over a burning ruined house, in flames. There is a wolf howling into the night, and a baboon holding a baby; beneath, a drowned woman with a skull.\ To read these pages now is an exercise in tragic irony, for we know what the TLS does not: that the Blitz is coming and that London will burn. On 22 June 1940, there is a positive review of a history of the Great Fire of London of 1666, in which the reviewer notes 'a strange and universal fascination' with the Great Fire. There was good weather that summer, and the Stratford Shakespeare Festival went ahead as planned, although with smaller audiences than anticipated, and on Saturday, 7 September 1940, a special issue is dedicated 'to the purpose of spreading the spirit of our literature abroad'. There are essays on the relationship between European and Englishliterature, and on reading habits in the Commonwealth, but presumably nobody read them, for at four o'clock that afternoon the Blitz began.\ There is no mention of the raids in the next issue, of 14 September 1940, and the issue of the following Saturday, when half of London was on fire, led with a praising review of a new dictionary of clichés. 'It is possible to welcome so powerful an ally in the defence of good English in an hour when official English is using unparalleled opportunities of destroying it,' the reviewer notes, and there is the usual recommendation for Novel of the Week: the historical romance Basilissa, by John Masefield. On 12 October, 'News and Notes' mentions a slight delay in the publication schedule for the four-volume Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature, and adds that the Reading Room of the British Museum has reopened, after a brief closure 'for protective work'. However: 'the Manuscript Reading Room will be closed until the danger of air attack is passed.'\ As I read them now, these issues of the wartime TLS are snugly bound in blue mock-leather, in the upstairs reading room of the British Library known as 'Humanities 2'. These survived, but once, in their unbound form, they were nervous loose pages and surely, in the burning city, they participated in a larger worry that fire would take all. I can only read the survivors, but once they must have worried that they could be lost, and I warm to their little acts of defiance.\ I read on, through 1941 and the following year - 'Notwithstanding the war the "Twickenham" edition of the Poems of Alexander Pope, which is to be completed in six volumes, continues its scholarly course' - and in time I come to 12 June 1943, the day my grandfather was lost, and I find, of course, that the world goes on. Novel of the Week is The Serpent, by Neil M. Gunn. The cover celebrates a new volume of traveller's memoirs, and there is a crossword, opaque to me (6 across: 'A nail-biting giant', 4 letters), and then, on page 284, a short review of two airmen poets.\ They have been forgotten now. Thomas Rahilley Hodgson was twenty-six when he was shot down, in May 1941, but before then he had written a wintry poem called 'Nocturne':\ The grey sky overcast, and dying, the sun red tangled, huge among the bare branches of trees. Last call of birds, and night coming, cries of children slim and clear along dusk. Fear of mortality.\ He shares this fear with the second poet in the review, Alan Rook, who wrote:\ The living are dying daily. And death shall come not in the moment of expected danger but only when the reaper is ripe for the corn.\ On this day of unexpected death, in a small town in Sussex fifty miles from London, my grandmother waited for news, and, further away, my grandfather fell from the sky. Nobody noticed, but two sentimental poets in the pages of the TLS.\ Again and again, in reading my way after the poets of this war, I have a sense of another conversation, just submerged. I hear the speeches, by the editors and the famous literary men, loud and certain; and yet, as from another room, a hum; of people speaking softly, of something more or less unspoken. In May 1946, a year after the war ended, Edmund Blunden wrote an essay for the TLS. 'The second war with all its novelty of aspect and its shifting of emphasis has not weakened the commanding position of Wilfred Owen in the poetry of the age,' he insisted, and went on to elaborate the familiar music:'nor have its own poets varied the themes so powerfully as to throw upon his pages any shadow of supercedings.' Blunden was himself a poet of the First World War, and had edited the 1931 edition of the poems of Wilfred Owen. He wrote: 'Owen's imagination, artistry, and compassion remain, now that the fumes and the volleys have left the daylight to itself and us, as a practically perfect achievement', and approvingly quotes Sir Osbert Sitwell on Owen: 'If he can be properly called a War Poet - since, greater than that, he was a Poet - he may be the only writer who answers truly to that description.'\ The emblematic story of British war poetry in the twentieth century is that of Wilfred Owen, perfect and dead. He wrote the poems that war poetry is supposed to sound like, and that children can recite:\ Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs And towards our distant rest began to trudge.\ Like every generation, I learned these at school. They make ideal reading comprehension exercises, for they ask not that you know much, but that you feel deeply; their rhymes are inviting and sad, and they have a wistful urgency that is very hard to refuse. 'Above all I am not concerned with Poetry,' Owen wrote in the famous preface to the first collection of his poems: 'My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.' The work these poems do, then, is to elicit from us our sympathy, and they do so as they rhyme emotion with location. Owen made a landscape famous - mud, sludge, trudge, the trenches along the western front of the First World War - and rendered it as poetry.\ Owen's distinctive poetic achievement lay in the meeting of his place and his verse, and his own life was a sad paraphrase of the war as a whole. He was killed on 4 November 1918, one week before the end of the war, and, as the myth records, the bells were ringing theArmistice when the telegram reached his parents in Shrewsbury. He wrote this, too: in 'Anthem for Doomed Youth', when he traces 'The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells; / And bugles calling for them from sad shires'. And since he wrote his own death, we are in the presence not of an individual but of a principle, and perhaps we need not look any further. Owen lived an idea about poetry, for his admirers and his editors, which was made perfect by his death. 'All that was strongest in Wilfred Owen survives in his poems,' wrote his friend and mentor Siegfried Sassoon, in a brief introduction to the first collection of Owen's poems. The man has become the poems, and Sassoon goes on to insist: 'any superficial impressions of his personality, any record of his conversation, behaviour, or appearance, would be irrelevant and unseemly.'\ But this is too strict, for people do not really live as ideas. We live by accident and once, Wilfred Owen imagined that he might be someone else. In his letters, we meet a variable young man, and in August 1916, during military training, he thought he wanted to be an airman instead of a soldier. As he wrote to his mother, he was applying for transfer to the Royal Flying Corps:\ Flying is the only active profession I could ever continue with enthusiasm after the war.\ Once a certified pilot, the pay is £350. The Training lasts three months.\ By Hermes, I will fly. Though I have sat alone, twittering, like even as it were a sparrow upon the housetop, I will yet swoop over Wrekin with the strength of a thousand Eagles, and all you shall see me light upon the Racecourse, and marvelling behold the pinion of Hermes, who is called Mercury, upon my cap.\ Then I will publish my ode on the Swift.\ If I fall, I shall fall mightily. I shall be with Perseus and Icarus, whom I loved; and not with Fritz, whom I did not hate. To battle with the Super-Zeppelin, when he comes, this would be chivalry more than Arthur dreamed of.\ Perhaps the weather was fine, that August in Essex, and perhaps ground training was dull, but he was looking at the sky and considering what might be, and his motives are a strange blend of the practical and the mythic: the £350 pay, the echoes of Hermes. We can follow his jittery associations: from a worry about work to flight, and to sparrows and eagles over the town where he grew up, and then to his own poetry.\ He had written 'The Swift: An Ode' more than three years earlier, in imitation of Keats's 'Ode to a Nightingale', and it is clumsy - 'to be of all the birds the Swift!' it longs - but suggests some of the possible glamour Owen saw in learning to fly. 'Waywardly sliding and slinging, / Speed never slacking,' it wonders:\ Easily, restlessly flinging, Twinkling and tacking; - Oh, how we envy thee thy lovely swerves!\ Owen is collecting the materials for a poetry of air war. When he thinks of Zeppelins, he thinks also of the swifts, of Greek myths and Arthurian heroes and the inevitable fall; and of what he will write; and of how others shall marvel at this airman poet above.\ The Royal Flying Corps rejected Owen's application for a transfer, and on New Year's Eve of 1916 he was sent to the mud of northern France, to the trenches he then made famous in what Cecil Day Lewis later called 'probably the greatest poems about war in our literature'. The earlier, doubtful Owen - envious of the swift, of the airmen - was soon forgotten. 'During the weeks of his first tour of duty in the trenches, he came of age emotionally and spiritually,' continued Day Lewis, in the preface to his 1963 edition of Owen's poems, collapsing the man into the landscape: 'The subject made the poet.'\ The poet needed the trenches, and Day Lewis continues: 'though this ubiquitous landscape surpassed all the imagined horrors ofDante's Inferno, it provided the soldier poets with a settled familiar background, while trench warfare gave them long periods of humdrum passivity.' Without the trenches, then, there could be no poetry, and he elaborates:\ Such conditions - a stable background, a routine-governed outer life - have so often proved fruitful for the inner lives of poets that we may well attribute the excellence of the First-War poetry, compared with what was produced in the Second War - a war of movement - partly to the kind of existence these poets were leading: another reason could be, of course, that they were better poets.\ This is a strange and poignant claim to make in what is, after all, the introduction to a collection of First World War poetry, but Day Lewis is here not really writing about Owen at all. He is writing about himself, and explaining his own failure to become a similar poet of the Second World War.\ Cecil Day Lewis was supposed to be a war poet. In his 1935 collection A Time to Dance, he writes poetry about his own obsession with war as a form of poetry:\ In me two worlds at war Trample the patient flesh, This lighted ring of sense where clinch Heir and ancestor.\ He is the heir of the First World War poets; Wilfred Owen is his ancestor. He continues, in imagery that is again borrowed from the poetry of the previous war:\ The armies of the dead Are trenched within my bones, My blood's their semaphore, their wings Are watchers overhead.\ The gesture towards the air is more fully developed in his next collection, Overtures to Death and Other Poems, published in October 1938. In the poem 'Bombers', he imagines a flight of planes overhead:\ Black as vermin, crawling in echelon, Beneath the cloud-floor, the bombers come: The heavy angels, carrying harm in Their wombs that ache to be rid of death.\ The image here of a womb is continued in the next stanza, where the 'iron embryo' of the bomber longs to give birth to 'fear delivered and screeching fire'.\ Here is the promise of a poetry specific to the Second World War. It builds upon the tight fury and intensely physical metaphors of the First World War poets, and yet the form of its menace is particularly modern. 'Children look up,' he writes, for this type of war is no longer bound to a single landscape; it is in the air, and as the 'Earth shakes beneath us: we imagine loss'. He begins to sketch a new poetry, of terror bombing, and to imagine the broken fields of London, Hamburg, Coventry, Dresden; and yet once the war broke out, he rapidly abandoned this line of imagery. At Easter 1938, he bought a cottage in Dorset, and by the end of the summer had withdrawn his membership of the Communist Party in London and moved his wife and two sons to the countryside. He started an affair with the wife of a local farmer, and spent the autumn of 1939 finishing the latest in a series of pseudonymous thrillers he wrote to make money. 'Malice in Wonderland, the tale of a deranged murderer running riot in a holiday camp,' notes his biographer, was 'published in the summer of 1940'.\ The poetry he wrote in these years embodies this turn away from the war. In October 1940, as the Blitz was beginning in London, he published a translation of Georgics, Virgil's cycle of instructional poems about farming, with a prefatory poem that opens: 'Poets arenot much in demand these days'. He goes on: 'Where are the war poets? the fools inquire', and concludes that 'We have turned inward for our iron ration'. The cycle as a whole glorifies the pastoral scene, apart from the preoccupations of war.\ Oh, too lucky for words, if only he knew his luck, Is the countryman who far from the clash of armaments Lives, and rewarding earth is lavish of all he needs!\ exclaims one stanza, and surely here Day Lewis found an echo of his own retreat. Always in these poems he is distracted from the war. In May 1940, he enrolled in the local platoon of the Home Guard, and wrote of his military experience in a collection published as Poems in Wartime. 'The farmer and I talk for a while of invaders,' one poem begins: 'But soon we turn to crops'.\ We have been at this moment before, when a poet comes suddenly aware of a new poetry of this war; and yet, in the moment of suggestion, turns away, made self-conscious by the task. We have seen the theme of a poetry of air war raised, and dropped, and yet it is at this pause, when I hear the poets saying, no war poetry, that I start to listen for the rumble in the distance, as the earth shakes beneath us and we imagine loss. The bombers are never far behind. In the spring of 1941, Cecil Day Lewis took a job at the Ministry of Information, in a building near the shattered squares of Bloomsbury that haunted Virginia Woolf. Some nights the raids on London were so bad that Ministry officials slept on bunk beds in the basement, and Day Lewis went on writing, a series of pamphlets for popular distribution by the Ministry as well as his own poems that would then be published in his collection Word Over All of 1943. In the brief window between Woolf's suicide at the end of March 1941, and my grandfather's first bombing raid six weeks later, Day Lewis returned to the suspended theme of bomber poetry, and became a secret war poet.\ 'I watch when searchlights set the low cloud smoking / Like acid on metal,' Day Lewis wrote in 'Word Over All':\ I start\ At sirens, sweat to feel a whole town wince And thump, a terrified heart, Under the bomb-strokes.\ But it is not enough, yet, to report of what he saw, for he knows that where he may have had a terrified night, the truer sufferings were elsewhere. 'These, to look back on, are / A few hours' unrepose,' he continues: 'But the roofless old, the child beneath the debris - / How can I speak for these?' The poetry of air bombing requires a particular imaginative sympathy absent from other war poetry, and it must play between telling and deferring the tale: between the poet who survived and the others who died that night. And it is only in this fine balance, pitched between condemnation and celebration, between terror and relief, that the poem may also invoke the bombers themselves. They are above, of course, out of the burning city, but they are initiating the bomb-strokes, and so they too must be invited to speak. A little later in the collection, in 'Airmen Broadcast', Day Lewis challenges the bombers to compose a poetry of their own, and since it encapsulates so much of this moment it is worth quoting this poem in its brief entirety:\ Speak for the air, your element, you hunters Who range across the ribbed and shifting sky: Speak for whatever gives you mastery - Wings that bear out your purpose, quick-responsive Finger, a fighting heart, a kestrel's eye.\ \ Speak of the rough and tumble in the blue, The mast-high run, the flak, the battering gales: You that, until the life you love prevails, Must follow death's impersonal vocation —Speak for the air, and tell your hunter's tales.\ If we read these two poems side by side, we see Day Lewis imagining himself as both bomber and bombed. And yet, by isolating himself from each - he is not with the roofless old, nor hunting through the ribbed and shifting sky - he is forming a space for the poet in this war, one who is partly a victim, shivering in his basement bunk, and yet conscious also of the greater loss; and one who partly longs to be an airman. 'How can I speak for these?' he asks, and commands: 'Speak for the air'. Cecil Day Lewis is summoning the double-subject into being. It was not automatic. The TLS and the guardians of English literature said, no verse, but here perhaps before them, in the quiet between the bombing, another poetry was beginning.\ Perhaps this is what a poetry of air bombing might mean: perhaps it is always of the near distance, its sufferings always at a remove. Perhaps the poets are the voices from the other room, almost overheard, and the poems never quite take the form we anticipate. While Day Lewis was working for the Ministry of Information in Bloomsbury, he was not writing only the poems that appear safely now in his Collected Poems. He was working also on a series of cheap pamphlets that sought to celebrate the war effort, and in one of these, called simply Bomber Command, he returns to the air war. Like all government documents, it appeared anonymously; it never invited anyone to read it as a poem.\ The pamphlet presents itself as a strict narrative history of the first phase of the bomber war. The title page promises 'The Air Ministry Account of Bomber Command's Offensive Against the Axis, September, 1939 - July, 1941', and it begins quite routinely at the beginning, with a flight by a Blenheim to take reconnaissance photographs of the German fleet on the first day of the war. Accompanied by maps, and statistics, and glossy photographs of grinning bomber crews, solid in full gear, it tells of the early raids on the German fleet, of the first winter and spring of the war, and then the first attacks on a land target, the seaplane base at Sylt, off the Danish coast, in March 1940. There are leaflet drops, and crash landings,and as Holland falls to the Germans the British raids follow them. By May 1940, Bomber Command is raiding mainland Germany, particularly targets 'in the district of the Ruhr, which is the most important industrial area in Germany'. Through the summer of the following year, the raids intensify, and by the end we are assured that 'the aircraft of Bomber Command were over Germany twenty-six out of twenty-eight nights.'\ It makes compelling reading, this modern epic of industrial war, and yet apologizes for the repetitions of its subject. Bombing operations are 'not dramatic in the accepted sense of the word', the pamphlet insists, and explains:\ To describe every bombing attack carried out against Germany would be to transform this narrative into a catalogue of raids. Such makes dull reading. This should be so. The most successful raids are those in which no incident occurs; the best crew, that which takes its aircraft, unseen and deadly, to the target, bombs it and flies home again through the silence of the night. In essentials all bombing operations are the same.\ Told as a story rather than a catalogue, the bomber war demands characters and a setting, so we meet the members of an abstract crew: the pilot, who 'must be imaginative, yet not be dismayed by his own imagination', and the navigator, 'the key man in a bomber aircraft', who directs the plane and aims the bombs. He has the hardest job of all, for 'Darkness, clouds, air currents, all singly or together, are his foes.' Life on base is not half bad, we are told, and the atmosphere 'may be likened to that found in an inn frequented by mountaineers'. We see pictures of these men in their planes, often looking away from the camera as if to feign duty, and of the operations rooms, and because a story needs not only a cast but also a crisis, we are told about a night that almost went wrong.\ 'Münster, an important railway junction, was bombed five nightsrunning from the 6th to 10th July,' the stirring anecdote begins, and goes on:\ The crew of a Wellington have good cause to remember one of the recent attacks on Münster. When on the way home it encountered and shot down an enemy fighter, which, however, set the bomber's starboard wing on fire. It was over the sea and the crew stood small chance of being picked up if they baled out. One of them, a sergeant, volunteered to climb out on to the wing and extinguish the flames. He climbed out of the Astro' hatch, kicked hand- and foot-holds in the fabric and beat out the fire with an engine cover. He had a rope round his waist when out on the wing; but had he lost his hold it would either have snapped or, helpless in the slipstream, he would have been battered against the tail fin. The Wellington reached its base safely.\ I stop here, stunned not by the surreal bravery of this scene but its familiarity. I know what happened this night, because my grandfather was bombing Münster in July of 1941, on the night of the 3rd, and then again on the 5th, and on the 7th and again on the 8th, and on the 7th his Wellington was attacked by an enemy fighter. 'Sgt Swift claims enemy aircraft shot down by rear gunner,' runs the clipped official history told in the Operations Record Book for 57 Squadron, and goes on: Attacked by Me. 110, causing damage to rear turret and stbd [starboard] aileron and elevator. Front gunner + rear gunner fired long bursts, believed secured hits.' Nothing here indicates surprise, but this moment was exceptional enough to form the basis of my grandfather's citation for the Distinguished Flying Cross four months later, and the citation tells another slightly different version of the same night, placing its emphasis now on the combat and not the damage. 'Whilst participating in an attack on Münster, Pilot Officer Swift's aircraft was engaged in a 15 minute encounter with a Messerschmitt 110,' the official citation runs: After six attacks the enemy broke away in a vertical dive. It was most certainly damaged, if not destroyed.'\ What moves me most now, reading of these wild heroics more than sixty years later - more than a lifetime later - is that after this night, he went out again, to Münster on the 8th and then to Cologne on the 10th. Perhaps my grandfather's raid was not even the same as the one in the pamphlet: perhaps another Wellington raiding Münster was attacked by another Messerschmitt, and another starboard wing was burned; and another crew trailed home, relief whistling through their teeth. Perhaps this was simply a busy season for such frisky heroics. 'In essentials all bombing operations are the same,' wrote Day Lewis, and perhaps in the poetry of bombing there are no certain heroes, but only repetitions.\ At the end of Day Lewis's pamphlet on Bomber Command is a short section, called 'One Thing is Certain', which celebrates precisely this quality of repetition. 'The attack on the enemy continues without pause,' he writes at the close, and moves into a flurry of quotation. 'They plod steadily on, taking their aircraft through fair weather or foul, night after night,' he promises, following the witches in Shakespeare's Macbeth as they chant: 'Fair is foul, and foul is fair, / Hover through the fog and filthy air'. 'These twentieth-century "gentlemen of the shade, minions of the moon" have accomplished much in twenty-two months of war,' he continues, and now the bombers are paraphrasing Falstaff's crew in Shakespeare's Henry IV, misbehaving with charm. 'By day they will go o