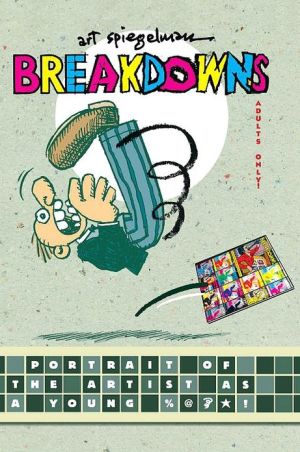

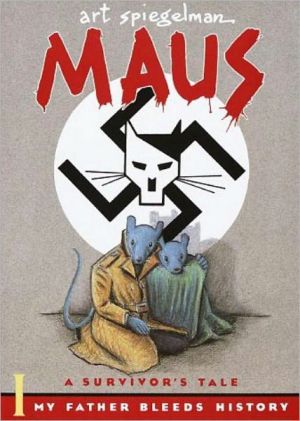

Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!

The creator of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus explores the comics form...and how it formed him!\ This book opens with Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!, creating vignettes of the people, events, and comics that shaped Art Spiegelman. It traces the artist's evolution from a MAD-comics obsessed boy in Rego Park, Queens, to a neurotic adult examining the effect of his parents' memories of Auschwitz on his own son.\ The second part presents a facsimile of Breakdowns, the long-sought...

Search in google:

The creator of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus explores the comics form...and how it formed him!This book opens with Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!, creating vignettes of the people, events, and comics that shaped Art Spiegelman. It traces the artist's evolution from a MAD-comics obsessed boy in Rego Park, Queens, to a neurotic adult examining the effect of his parents' memories of Auschwitz on his own son.The second part presents a facsimile of Breakdowns, the long-sought after collection of the artist's comics of the 1970s, the book that triggers these memories. Breakdowns established the mode of formally sophisticated comics that transformed the medium, and includes the prototype of Maus, cubist experiments, an essay on humor, and the definitive genre-twisting pulp story "Ace Hole-Midget Detective."Pulling all this together is an illustrated essay that looks back at the sixties as the artist pushes sixty, and explains the obsessions that brought these works into being. Poignant, funny, complex, and innovative, Breakdowns alters the terms of what can be accomplished in a memoir.The Barnes & Noble ReviewA psychoanalyst once told me that a deeply traumatic event in someone's life sometimes grew into a "nuclear integrative phantasy." When I asked him what that meant, he said, "It's nuclear because it becomes the central fact of the person's existence, it's integrative because it shapes and distorts everything else in his life, and it's a phantasy because not everything that happens to him is in fact related to it, except in his mind and feelings." He went on: "The best large example of this phenomenon that I know of is the way the Holocaust affected many of its survivors, and often their children. It took over as the central organizing factor of their lives, everything revolved around it, and they had a difficult time not seeing every experience -- both after and before the trauma -- as somehow connected to it." He then added, ruefully, "And who can blame them?"

\ Douglas WolkIn the 1970s, nearly all of Spiegelman's work was years ahead of art-comics trends, from the original version of "Maus" (a three-page sketch about Spiegelman's father's experiences during the Holocaust, which evolved into his two-volume magnum opus in the '80s) to "The Malpractice Suite," an extended mutilation of an old "Rex Morgan M.D." strip that becomes more convoluted and deranged with every panel. Spiegelman draws them all with a frantic intensity, as if his pen were about to slash through his drawing board and crack his table in half.\ —The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThis reprint of Spiegelman's 1978 collection of comics is a must-have for any comics aficionado, art-house dude, hipster or anyone who ever thought to himself, "Hmm, comics are kinda cool." It will also be liked by anyone who ever enjoyed Kafka or anything postmodern enough to be in McSweeney's. There's still enough here for regular people to enjoy, too. The 30-page memoirish introduction, all done in comics (in which we get to see Spiegelman mess up his son's mind the way his was messed up) explains how comics came to be the shining light for so many messed-up adolescent boys: "Mad warped a generation in the bland American 1950s-something that's been done before, but possibly not so well." The early comics are a revelation. Spiegelman gives us the story that led to Maus, and we see how he evolved from an R. Crumb-loving artist with neuroses pertaining to The Dick Van Dyke Show to a tight storyteller of anxious, modern folktales. One of the functions of the artist is to take us to hell and get us out in one piece. Spiegelman's early trips into hallucinatory darkness do this. We come out in one piece; it's not clear he did. (Oct.)\ Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.\ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsA reissue of the graphic artist's early, little-seen volume shows his formative work, while an extensive forword and afterword provide autobiographical context. Spiegelman (In the Shadow of No Towers, 2004, etc.) justifies the Joycean subtitle of this collection, as the seeds of his renowned artistry are here. He explains in his afterword that he was "startled" when his publisher suggested a reissue of 1978's Breakdowns, because its impact upon initial release had been minimal with both readers and fellow artists. Yet, he explains, "it was the resounding lack of response to Breakdowns that led directly to the 300-page Maus," which won the Pulitzer Prize and established the graphic narrative as something more than comic books for adults. While the earliest piece in Breakdowns provides a prototype for Maus, and the rest shows a range that extends from a detective serial (with a nod toward Picasso) to hardcore sexuality, the artist wasn't content here to let Breakdowns stand on its own. The graphic narrative that introduces the reissue is considerably longer than any of the pieces in Breakdowns, detailing the early years of the comics-obsessed artist, the profound influence of MAD magazine, the trauma of his mother's suicide, his pay-the-bills work designing bubblegum cards for Topps (including the Garbage Pail Kids) and his development of both a philosophy and an aesthetic that would result in comics being taken more seriously than they had been. "He dared to call himself an artist and call his medium an art form," he explains in the mostly textual afterword, as he became "infatuated with the cross-pollination of High and Low." Though much of the work for which the artist has becomecelebrated has been autobiographical, this reissue is revelatory as it traces his development. Fans of graphic novels in general and Spiegelman in particular will savor this. Agent: Suzanne Williams/Suzanne Williams Public Relations\ \ \ \ \ The Barnes & Noble ReviewA psychoanalyst once told me that a deeply traumatic event in someone's life sometimes grew into a "nuclear integrative phantasy." When I asked him what that meant, he said, "It's nuclear because it becomes the central fact of the person's existence, it's integrative because it shapes and distorts everything else in his life, and it's a phantasy because not everything that happens to him is in fact related to it, except in his mind and feelings." He went on: "The best large example of this phenomenon that I know of is the way the Holocaust affected many of its survivors, and often their children. It took over as the central organizing factor of their lives, everything revolved around it, and they had a difficult time not seeing every experience -- both after and before the trauma -- as somehow connected to it." He then added, ruefully, "And who can blame them?"\ In much if not most of his work, it seems to me, Art Spiegelman -- the comix-artist, graphic-novel genius who created Maus and Maus II, among other frighteningly original works -- has been directly or indirectly conjuring with the horror of his family's history of Holocaust survivorhood. Maus, of course, addressed this nightmare -- and Spiegelman's father's complex character and his own nervous breakdown and his mother's perhaps consequent suicide -- directly. In the Shadow of No Towers, about 9/11, took up the theme of murderous societal shock and trauma and drew overt comparisons to the Holocaust. But in addition to these (and some other) explicit demonstrations of the hold this subject has on Spiegelman's attention, I would say that it haunts and at least tangentially informs nearly everything he writes and draws. I would also say that this thematic recurrence nevertheless does not constitute an artistic "nuclear integrative phanstasy." Instead, it is an effort to keep it from doing so -- to transcend it by using it instead of being annihilated by it. A successful effort, at that -- at least aesthetically.\ In Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*! -- a reissue of "commix" bits and pieces first collected and published, in a very limited way, in 1978 -- Spiegelman re-gathers in a large-format presentation the various strips, doodles, "real dreams," and other fragments that originally made up Breakdowns and ultimately led to Maus. This republication is preceded by more recent material (also in graphic form) that shows the evolution of the artist's sensibility and preoccupations. Some of this material is brand-new. And it is followed by a new, illustrated autobiographical Afterword, in which the author explains, with his customary mordant self-scrutiny, how the stuff in Breakdowns originated, and what the comix scene was like in the heyday of Raw, The East Village Other, R. Crumb, and the Great Age of Psychedelia:\ By 1967, my virginity and mind were both long gone, and I began a hazy period of bouncing from Binghamton to the East Village, San Francisco and back.... I drew leaflets printed in runs of a hundred or so, passing them out in street corners and in parks when I wasn't passing out myself... They extolled LSD protested the war and as often as not had no discernable message at all.\ In the Afterword, Spiegelman runs through his evolution and education as an underground and even aboveground (Topps) comix artist. Starting with his first published drawing -- in 1961, when he was 13 -- in a small weekly newspaper in Queens, New York, he goes on to recount his meeting with R. Crumb and that unique artist's enormous influence on his own work, his immersion in mind-altering drugs and its effect on his ideas about narrative structure, his experimentation with grotesque images (one drawing showed a character called "The Viper" having sex with a hole in the neck of a boy's severed head, if I understand Spiegelman's description of this image correctly, as I'm afraid I do), and the point at which he understood he didn't have to deal with fictive phantasmagoria but could use his the story of his parents' and his own life to convey similarly disturbing but far more enlightening and cathartic images and words. "Instead of drawing the most appallingly lurid violence, I could now locate the atrocities present in the real world that my parents had survived and brought me into," as he puts it. In short: Maus.\ The Afterword also explains the development of Spiegelman's distinctive contributions to the destruction and krazy reconstruction of traditional comic strips -- an underground current that that welled up into the sort-of mainstream in the pages of Mad magazine, which itself had been part of the current's source. His realization that all media are, at least implicitly, about media, and that in the modernist era this concept was becoming more and more explicit, led him to experiment with playful and often unsettling defiance of comic-book conventions and High Art techniques. In the reprinting of Breakdowns, these experiments appear in the form of: the woodcut-like drawing technique of the seminal Maus strip; Cubist-style pictures of an old phonograph; the yellow-arrow icon that was used to direct a reader's attention from one panel to another when there might be confusion and that Spiegelman uses to direct the reader's attention in two or three different directions; a delightfully bewildering and upsetting strip called "The Malpractice Suite," in which, among many other peculiar effects, the characters' lower extremities differ from their upper bodies in, among many other things, species, nakedness and clothedness, and motor activity.\ Before the Breakdowns reprint, the panels, some of which appeared first in The New Yorker and which, taken together, add up to a sort of visual equivalent of the Afterword -- that is, as promised by the subtitle, "a Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!," -- stylistically quote Peanuts, Tintin, 3-D comic books, drawing-instruction manuals, EC Comics, etc. You know what? Let's just cut this short and say what should have become clear by now -- namely, that this whole publication is a hodgepodge. But it is an oxymoronically unified hodgepodge, for Spiegelman's always-surprising sensibility -- a kind of twisted but vital tree that has grown out of the dark soil of his parents' Holocaust suffering -- suffuses every word and every image here. His comically grim view of the world and himself and his family have allowed him to admit and depict psychologically complex truths about them -- and us -- that have broken new ground, from underneath, in both form and content.\ Two qualities redeem and unify the grimness, personal unhappiness, general inhumanity, and moral and pictorial fractures displayed here. One is the marvelous, closely observed incidental detail, in dialogue and pictures, which tells of keen observation and a deep joy in being alive, despite everything. This is the kind of digressive visual material that all great comic artists (well, all artists not of the Minimalist persuasion) use and that brings a smile to the face of readers and viewers. In one of his frightening "Real Dream" drawings, for example, there are four men's-room stalls shown, with toilet-paper dispensers all showing two sheets unrolled and one showing three. In the original Maus strip, there is a small inset scale showing that one representation of a mouse equals 15 mice. Dotted-line coupon margins run around one panel. Reversed signs are shown on the inside windows of bars and other establishments. There are small ceramic stress fractures at the top of the pitcher in one panel.\ The other redeeming aspect here is the fact of the existence of Spiegelman's work at all -- that is, in the first place. In its way, and along with other artifacts about the Holocaust and about other great trauma -- and like all art -- it answers and triumphs over the misery it portrays. Think of every Crucifixion painting by the Old Masters.\ So that's why and how Spiegelman's work surmounts the perduring historical nightmare that gave rise to it. That's how and why the Holocaust has not become a "nuclear integrative phantasy" for him -- as it definitely was for his father, who did not have the psychological and emotional wherewithal to escape the grip of the horror he went through. (And who can blame him?) And that's why and how his work applies to us all and to the human condition.\ Now, all that said, I nevertheless wish that Art Spiegelman would do something brand-new for us. Breakdowns has, for all its energy and inventiveness, a recycled flavor, even though its original publication consisted of 5,000 copies, half of them botched in the process of being printed. It's time for him to move even farther forward and amaze us all again. --Daniel Menaker\ Author of the novel The Treatment and two books of short stories, Daniel Menaker is former Executive Editor-in-Chief of Random House and fiction editor of The New Yorker. His reviews and other writings have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, and Slate.\ \ \