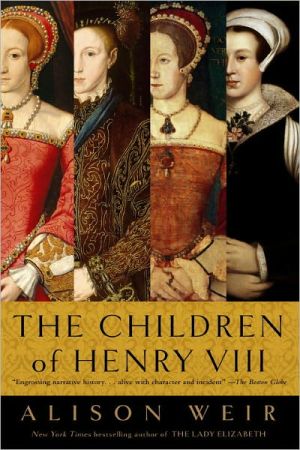

Catherine of Aragon: The Spanish Queen of Henry VIII

The youngest child of the legendary monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536) was born to marry for dynastic gain. Endowed with English royal blood on her mother's side, she was betrothed in infancy to Arthur, Prince of Wales, eldest son of Henry VII of England, an alliance that greatly benefited both sides. Yet Arthur died weeks after their marriage in 1501, and Catherine found herself remarried to his younger brother, soon to become Henry VIII. The history of...

Search in google:

The youngest child of the legendary monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536) was born to marry for dynastic gain. Endowed with English royal blood on her mother's side, she was betrothed in infancy to Arthur, Prince of Wales, eldest son of Henry VII of England, an alliance that greatly benefited both sides. Yet Arthur died weeks after their marriage in 1501, and Catherine found herself remarried to his younger brother, soon to become Henry VIII. The history of England—and indeed of Europe—was forever altered by their union.Drawing on his deep knowledge of both Spain and England, Giles Tremlett has produced the first full biography in more than four decades of the tenacious woman whose marriage to Henry VIII lasted twice as long (twenty-four years) as his five other marriages combined. Her refusal to divorce him put her at the center of one of history's greatest power struggles, one that has resonated down through the centuries— Henry's break away from the Catholic Church as, bereft of a son, he attempted to annul his marriage to Catherine and wed Anne Boleyn. Catherine's daughter, Mary, would controversially inherit Henry's throne; briefly and bloodily, she returned England to the Catholicism of her mother's native Spain, foreshadowing the Spanish Armada some three decades later.From Catherine's peripatetic childhood at the glittering court of Ferdinand and Isabella to the battlefield at Flodden, where she, in Henry's absence abroad, led the English forces to victory against Scotland to her determination to remain queen and her last years in almost monastic isolation, Giles Tremlett vividly re-creates the life of a giant figure in the sixteenth century. Catherine of Aragon will take its place among the best of Tudor biography. Publishers Weekly Born to Spain's powerful King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536) gave credibility to the rising Tudor monarchy into which she married. Guardian Madrid correspondent Tremlett (Ghosts of Spain: Travels Through Spain and Its Silent Past) eloquently fleshes out the 20-year reign of young Henry VIII's gracious, educated first wife, who intrepidly influenced foreign policy and, as regent, routed the Scots at Flodden Field while Henry less successfully led his army in France. Tremlett clearly favors his Catholic subject, giving her too much credit as the driving force behind opposition to the English Reformation. Still, his portrait of the often overlooked Catherine, who arrived as Henry was elevating his court to a glittering level, as England became firmly established as a European power--a position undermined by the "Great Divorce" from Catherine and the resulting alliance shifts. Tremlett's well-researched portrayal reads easily, and while recognizing Catherine's flaws, he restores the luster to a popular queen whose image was later reduced to a piously dour castoff. Tudor-era fans as well as scholars will appreciate this account. 16 pages of color illus. (Dec.)

Catherine of Aragon\ The Spanish Queen of Henry VIII \ \ By GILES TREMLETT \ Walker & Company\ Copyright © 2010 Giles Tremlett\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-8027-7916-8 \ \ \ Chapter One\ Bed \ London, the Bishop's Palace November 14, 1501\ The Spanish girl with the long, light auburn hair lay in bed waiting. It had been an exhausting day. She had been on show, watched by thousands of pairs of foreign eyes, since she first stepped out of the Bishop's Palace and into the cold, early winter morning air of London. She had done what was bid, maintaining her composure during the interminable hours of wedding ceremony and Mass. She, the bride, had walked elegantly across the raised walkways and stages in the cathedral, turning from one side to the other to show herself to the sea of staring faces below. Onlookers had gawked down from windows and rood lofts to get a view of her in her white silk Spanish dress with its strange hooped skirt. Cheering crowds had gathered on the streets, and inside the tumult had been such that some found it hard to follow what was happening. Her new in-laws were delighted.\ Her day, however, was by no means over. The bedroom at the Bishop's Palace bustled with activity. It had been busy, already, for the best part of two hours. A Spanish countess and an English duchess had previously fussed together over the making of the bed. An English earl had come to make sure they had done the job properly. He had even tested it out himself, trying out one side then the other to make sure it was comfortable enough and properly made. This, after all, was no ordinary bed. It was, as one chronicler of this most publicized of events put it, a "bedde of estate."\ Watched by the assembled company of women, the girl stepped into the bed. There was no privacy. Her helpers made sure that she was "reverently laid and reposed." And, so reposed, she awaited the pale, thin-lipped and auburn-haired fifteen-year-old she had just married.\ The young man with whom she had spent much of the day, but who she had barely ever spoken to, then entered the room. A train of ebullient friends, flunkies and officials entered with him. She could count on the fingers of one hand the number of times she had seen this serious, gentle-eyed youth before. His name, however, had been part of her life for as long as she could remember. He was Arturo, Arthur, a prince from the land that had given the world the exotic legends of Camelot. He was also, as eldest son of Henry VII, heir to the English throne. One day, it was assumed, she would be his queen.\ Those with Arthur had spent the best part of the afternoon drinking, dancing and seeing to their own "plea sure" and "myrthe." It is safe to assume that the young man had drunk his share of wine and ale as well. Arthur's younger brother—an energetic, excitable, robust and ruddy-cheeked ten-year-old prince called Henry— was probably deemed too young for this later stage of the proceedings. Young Henry had been the one who, earlier, had taken her hand and led her out of old St. Paul's Cathedral along the raised platform above the "tumult and multitude" of people packed inside. One of the company recalled that they found Catherine lying under the coverlet "as the manner is of queens in that behalf"—whatever he meant by, or knew about, that. Then, with a gaggle of people still watching, Arthur climbed in beside her. The book of royal etiquette stipulated, admittedly for slightly different circumstances, that the groom should be "in his shirte, with a gowne cast about him."\ The couple would have rested their heads on a special sheet covering the pillows. Layers of straw, canvas, a feather mattress (all suitably rolled on and beaten to get rid of bumps) and tightly stretched sheets lay beneath them. More sheets, blankets, rugs and, perhaps, a coverlet of ermine were above. The bed itself should have been a tester bed, with its posts supporting a full or half canopy above their heads. There may also have been curtains.\ Beside the girl's bed the bishops and prelates were reciting in Latin. This, at least, was a language she could understand. Much of the rest of the day's comings and goings outside the cathedral had been conducted in English— a language she was only just getting used to hearing. Most of the chatter in her chamber now would also have been in English—though a few would have known to address her in Latin or in French, a language that she could just about use herself. Few, excepting her own retainers, would have spoken the familiar Spanish of her home.\ There must have been something comforting about the bishops' incantations. For the girl knew about prayer. Priests, as both tutors and confessors, were the men she had come to know best in her fifteen years. Now they were praying for her to remain safe, in this bed, from the demons of the dark En glish night. The missal indicated the words they should use. "Custodi famulos tuos in hoc lecto quiescentes ab omnibus phantasmaticis daemonum illusionibus: custodi eos vigilantes ut in praeceptis tuis meditentur dormientes, et te per soporem sentiant: ut hic et ubique defensionis tuae muniantur auxilio," they would have intoned. Abraham, Isaac and Jacob— familiar Old Testament spiritual warhorses—were called on to add their power to the blessing.\ The bishops' presence here, sprinkling holy water on the princely bed, meant that the most important part of the day was due to begin. The young couple's duty, the priests were expected to remind them, was "crescant et multiplicentur in longitudine dierum"— to "grow and multiply throughout the length of your days." Soon the bishops withdrew. Fortified by a good-bye swig of wine and spiced sweetmeat, the noisy young men, the court functionaries, the bossy governess and all the rest left the newlyweds alone.\ Catalina, still getting used to hearing the sharp consonants of her name softened to the En glish word "Catherine," was one month off her sixteenth birthday. She was, or certainly should have been, a virgin. That was what the ambassadors sent by her parents, Isabel and Ferdinand, the powerful Reyes Católicos—the "Catholic Monarchs"—of Spain, had proclaimed to her father-in-law and his court just twenty-four hours earlier. Her husband, Arthur, Prince of Wales and heir to the throne of England, may have been younger, but his fourteenth birthday was already thirteen months behind him. Catherine herself had been of a marriageable and (by presumption, at least) sexually mature age for even longer. The wedding treaty had stipulated a marriage after Arthur's fourteenth birthday. By the mores of their time, they were old enough for what should have happened next. Had not her father- in- law, King Henry, been conceived when his own mother, Margaret Beaufort, was still just a twelve-year-old girl?\ This was, in fact, what it had all always been about. There had been years—most of her young lifetime—of waiting. Months of journeying across the mountains, valleys and sierras of her homeland had been followed by two attempts to get across the storm-battered sea to En gland. Weeks were spent processing through a strange, dark and damp land. Finally, with a display of pageantry never before seen in London, she had gotten married. All that had a single purpose. Her task was to join her native Spain to her newly adopted England. She was to do that by bearing children—preferably male—who would carry not just the blood of the Tudors but also that of the royal houses of Castile and Aragon. That task was meant to start in her very public wedding bed in the Bishop's Palace, just as soon as the onlookers had disappeared.\ Did they or did they not set about the business of "multiplying" that night? Did lust, hope or simple duty bring their young bodies—and perhaps their spirits—together? Or was it all too much for a pair of exhausted, inexperienced, overwrought or overexcited teenagers? Did they even know exactly how to perform what was expected of them? Only Catherine and her slight, serious-looking young husband ever knew what happened next. Did she find him to be of "good and sanguine complexion," as one of his friends remembered him that night? Or was he, underneath the gown and shirt, as startlingly "weak" and "thin" as one Spaniard who traveled with Catherine later described him? At the hearing years later in Zaragoza, Spanish witnesses who served Catherine in En gland were firm about his impotence. Arthur sneaked out of her room early "surprising everyone," with Catherine later pointing to a young boy in her ser vice and muttering to her ladies that "I wish my husband the prince was as strong as that lad because I fear he will never be able to have [sexual] relations with me."\ How, indeed, did they communicate their desires? Latin, learned from primers and practiced with tutors and priests, was the only language they really had in common. How did that Latin sound now, in the intimacy of a shared bed?\ Even doña Elvira, the bossy and troublesome lady mistress who Catherine had brought with her, seems not to have snooped on them—though she would later claim to know exactly what did, or did not, happen that night. Perhaps she was the source of later Spanish claims that there had been no virgin's blood left staining the sheets.\ The question of what took place here on top of straw, canvas and feathers would become, a quarter of a century later, a battleground around which changes of epic proportions occurred. For the boy died before he could become king, leaving Catherine of Aragon a childless sixteen-year-old widow. She went on to become the first wife of his young brother, Henry VIII. Much later, Henry would ask the pope for permission to abandon her because of her sexual encounters with his brother. His chances of obtaining a successful annulment, then, hung on the idea that something had actually happened in that wedding bed.\ Sex, royalty, power and Europe an politics all met on the nuptial mattress. The essential ingredients of what her twenty-first-century countrymen would come to call a culebrón, a soap opera, were all here. Gossips and intellectuals from Bristol to Bologna all had their views on whether the girl and the boy had fulfilled what was meant to be their destiny and whether she had sinned by marrying her husband's brother. It was only then, as the supposed details of her sex life were aired in open court in London and Zaragoza, that Catherine gave her own version of that night. She insisted that nothing at all had happened. Catherine, who tried so insistently to be perfect, had failed in her marital duties. Her Spanish family, among others, had hoped for more.\ Chapter Two\ QUEEN \ Toros de Guisando September 19, 1468\ The four bulls of Guisando were lined up on an exposed esplanade where the foothills of the Gredos Mountains fall south toward the vast plain of central Spain, the meseta. Huge granite beasts with long backs, they stood in obstinate, stony silence as they had done for centuries. If the four Toros de Guisando—a first sculptural suggestion of the long and complex relationship of Catherine of Aragon's homeland with the ox and the bull—remain a mystery today, then they must have seemed supernaturally strange in the year 1468.\ The potency of this image brought two groups of riders to this spot on a cool, clear September morning seventeen years before Catherine's birth. They had come, after all, to make peace. The bulls were to be silent notaries to an agreement, hammered out in advance, settling the future of Castile. A kingdom long racked by bloody internal squabbles was making yet another attempt at putting out the fires of civil war. The setting had been chosen carefully. Even in the late fifteenth century, politics and presentation went hand in hand.\ The king arrived, as kings do, with as much pomp as could be summoned up in open countryside beside a small brook several miles from the nearest town or village. There were fanfares of trumpets as Enrique IV of Castile led a small army of some thirteen hundred men to the site where the stone bulls stood. Enrique was a striking man. Tall, blond and well built, he had broken his nose as child. The accident left him with an adult face that made him look, depending on who you listened to, like either a terrifying lion or a foolish monkey.\ His rival was somewhat more low- key. She was, exceptionally, a woman. This was not a time when queens regnant—or those who aspired to the position—were either plentiful or particularly welcome in Europe. This unusually fair-haired and pale-skinned Spanish woman "with eyes between green and blue" rode not a horse, but a mule. The animal, in turn, was led by a priest. There was, however, no attempt at humility here. The woman riding the handsomely and expensively harnessed mule was a king's daughter, Isabel de Trastámara. She was seventeen years and four months old and fast becoming wise beyond her age. She was both half sister to Enrique and challenger for his crown. A train of some two hundred horse men followed her. The man holding the mule's reins was Archbishop Carrillo of Toledo, primate of Spain—a formidable warrior priest and one of the wealthiest and most powerful political players in the land. He was also Isabel's chief ally. The records do not say whether he was wearing the same scarlet cloak with a white cross that he was said to wear over his armor when leading his men into battle. The evening before, late into the night, he had tried to change the princess's mind about making peace. That morning, after celebrating Mass, Isabel had handed him a written pledge that she would make sure her brother and the strongmen who controlled him did not punish Carrillo for his loyalty to her. He, and his lands, would remain safe.\ Isabel had chosen peace. The conditions were by no means all favorable to her, but they were worth it for the one major concession they included. She was to be proclaimed her half brother's heir—the future queen of Castile. "If I do have this right, give me the brains and energy to, with the help of Your arm, pursue and achieve it and bring peace to this kingdom," she said before setting out. The "arm" she referred to was not the very worldly and occasionally sword- wielding arm of the archbishop but that of the entity who ultimately judged and decided everything in her world—God.\ Isabel had become Enrique's challenger by chance. Her father, the weak and malleable Juan II, placed her well down the order of succession on his death in 1454. Above her were not just Enrique and her full brother Alfonso, but also the future children of both. Castile's violent nobility, headed by the Grandes or Grandees, had long played a terrible game with their monarchs in which it was those behind the throne who mattered as much, if not more, than whoever was sitting on it. Enrique was, in any case, one more in a line of monarchs who had long proved ineffectual. His nickname, the Impotent, was garnered from what appeared to be a complete inability to consummate his marriages—and the resulting cuckoldry to which he was submitted by his second wife, Queen Juana. The nickname could just as well, however, have referred to his inability to control his kingdom.\ In one of the least dignified moments of his reign, an effigy of the king dressed in mourning had been placed on a mock throne on scaffolding erected outside the imposing, crenellated walls of Avila. There, on a summer's day in 1465, a group of the country's most powerful men—including the archbishop of Toledo—ritually humiliated the effigy in front of a crowd of jeering onlookers. A toy crown was torn off his head. The scepter and sword were wrenched from his hands. The marshal of Castile, Diego López de Estúñiga, then knocked the dummy to the ground, hurling foul-mouthed abuse at it. The heavy-booted nobles had then set about this king substitute, kicking him and stamping on his limp body to angry cries of "¡A tierra, puto!" Down on the ground, you bastard! They did not like this king. So they invented one of their own. Their pretender was Enrique's half brother Alfonso—aged just eleven years old.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Catherine of Aragon by GILES TREMLETT Copyright © 2010 by Giles Tremlett. Excerpted by permission of Walker & Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Contents\ Map....................xi\ Family Tree....................xii\ Introduction....................1\ 1 Bed....................7\ 2 Queen....................12\ 3 Birth....................20\ 4 Betrothed....................26\ 5 Infanta....................33\ 6 Alhambra Princess....................47\ 7 Adios....................55\ 8 Land....................62\ 9 On Show....................70\ 10 Wedding....................76\ 11 Silence and Sadness....................81\ 12 Married Life....................88\ 13 My Husband's Brother....................94\ 14 Bleed Me....................102\ 15 Deceived....................110\ 16 Confessions....................120\ 17 Ambassador....................125\ 18 Married Again....................132\ 19 Party Queen....................140\ 20 An Heir....................151\ 21 Motherhood....................155\ 22 Bedroom Politics....................159\ 23 War....................166\ 24 And Peace....................175\ 25 Daughters....................183\ 26 A Match for Mary....................190\ 27 My Sister's Son....................198\ 28 Infertility and Infidelity....................208\ 29 Bastard....................218\ 30 Divorce: The King's Secret Matter....................224\ 31 Virginity....................232\ 32 Disease....................239\ 33 Never with the Mother....................244\ 34 God and My Nephew....................248\ 35 The People's Queen....................253\ 36 Spies and Disguises....................260\ 37 Defiance....................267\ 38 Ghostly Advice....................272\ 39 Carnal Copulation....................277\ 40 The Lull....................282\ 41 Poison....................294\ 42 Alone....................303\ 43 The Queen's Jewels....................311\ 44 Secrets and Lies....................317\ 45 That Whore....................322\ 46 A "Bastard" Daughter....................326\ 47 Draw, Hang, Quarter....................335\ 48 Prisoner....................345\ 49 The Terror....................351\ 50 Death and Conscience....................360\ Afterword....................366\ Acknowledgments....................371\ Notes....................373\ Bibliography....................403\ Index....................417

\ Publishers WeeklyBorn to Spain's powerful King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, Catherine of Aragon (1485–1536) gave credibility to the rising Tudor monarchy into which she married. Guardian Madrid correspondent Tremlett (Ghosts of Spain: Travels Through Spain and Its Silent Past) eloquently fleshes out the 20-year reign of young Henry VIII's gracious, educated first wife, who intrepidly influenced foreign policy and, as regent, routed the Scots at Flodden Field while Henry less successfully led his army in France. Tremlett clearly favors his Catholic subject, giving her too much credit as the driving force behind opposition to the English Reformation. Still, his portrait of the often overlooked Catherine, who arrived as Henry was elevating his court to a glittering level, as England became firmly established as a European power--a position undermined by the "Great Divorce" from Catherine and the resulting alliance shifts. Tremlett's well-researched portrayal reads easily, and while recognizing Catherine's flaws, he restores the luster to a popular queen whose image was later reduced to a piously dour castoff. Tudor-era fans as well as scholars will appreciate this account. 16 pages of color illus. (Dec.)\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalSince the life of Catherine of Aragon was pivotal in the history of England and in the religious reformation of much of Western Europe, it is surprising to learn that there has been no full-length biography of her since the 1970s. Tremlett (Ghosts of Spain) has set out to remedy this deficit and approaches Catherine's life from a Spanish perspective rather than the more frequently used English lens. The familiar components of Catherine's story emerge from this narrative, interestingly if sporadically highlighted by less-well-known primary-source material from an ecclesiastical tribunal held in Zaragoza, Aragon, in 1531, to gather evidence on the validity of Catherine's marriage to Henry VIII. This testimony was, as might be expected, very different from that of the dramatic hearings held at Blackfriars in London. Tremlett skillfully weaves her sources into a humanizing picture of this formidable woman. VERDICT This biography should appeal to a wide audience with an interest in women's, Spanish, or English history.—Tessa L.H. Minchew, Georgia Perimeter Coll., Clarkston\ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsThe Madrid correspondent for theGuardianfollows the sad, tragic life of Catherine, first wife of Henry VIII, from her native Spain into the bloody whirlwind of Tudor England.\ Tremlett (Ghosts of Spain: Travels Through Spain and Its Silent Past, 2007) begins with a question still dividing historians: Did Catherine consummate her brief marriage to Henry's short-lived older brother, Arthur, Prince of Wales? All Henry's legal efforts to invalidate his marriage were based on his contention that the marriage had been consummated, something Catherine vigorously denied the rest of her life. Initially, the author focuses on the Spanish side of the story, looking carefully at Catherine's roots. Once she arrived in England, however, and once Henry's court began to fracture over the issue, Tremlett must rely on the same biased witnesses and documents used by Catherine's many previous biographers. Consequently, there's not much new here, but a slightly different slant, perhaps a more compassionate heart. Tremlett's journalistic chops are in evidence, however, and the well-written narrative moves briskly, if inevitably, through the wedding, the early years of marriage—we learn a lot about Tudor food and clothing and customs—the extraordinarily difficult childbirth experiences of Catherine, the healthy birth and, finally, Mary (who later became England's Queen "Bloody" Mary Tudor). The author chronicles Henry's occasional infidelities and his blinding, corrosive passion for Anne Boleyn, which, in part, accelerated the English Reformation and for decades splashed the blood of martyrs across the countryside. Tremlett credits Catherine for not encouraging a Spanish invasion to save her and Roman Catholicism..\ A trek along a familiar trail conducted by a personable, able guide.\ \ \