Chasing Monarchs: Migrating with the Butterflies of Passage

The monarch butterfly is our best-known and best-loved insect, and its annual migration over thousands of miles is an extraordinary natural phenomenon. Robert Michael Pyle, "one of America's finest natural history writers" (Sue Hubbell), set out late one summer to follow the monarchs south from their northernmost breeding ground in British Columbia. CHASING MONARCHS tells the engrossing story of his adventurous journey with these graceful wanderers—down the Columbia, Snake, Bear, and Colorado...

Search in google:

The monarch butterfly is our best-known and best-loved insect, and its annual migration over thousands of miles is an extraordinary natural phenomenon. Robert Michael Pyle, "one of America's finest natural history writers" (Sue Hubbell), set out late one summer to follow the monarchs south from their northernmost breeding ground in British Columbia. CHASING MONARCHS tells the engrossing story of his adventurous journey with these graceful wanderers—down the Columbia, Snake, Bear, and Colorado rivers, across the Bonneville Salt Flats, and through the Chiricahua Mountains to Mexico, returning north along the California coast. Part travelogue, part scientific study, CHASING MONARCHS is one of the most fascinating books ever written about butterflies. "[Pyle's] delightful anecdotes, thought-provoking philosophical questions and personal passion make this chronicle a potential classic" (Monarch News). Monarch News [Pyle's] delightful anecdotes, thought provoking philosophical questions and personal passion makes this chronicle a potential classic.

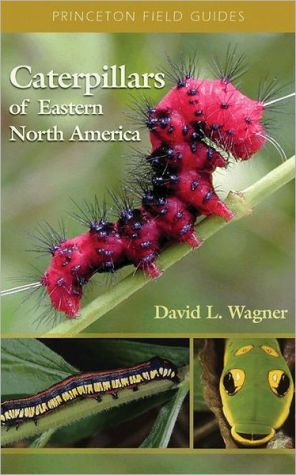

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ Similkameen\ \ \ It was the time of asters. Purple asters, mauve asters, tiny white asters. Summer was slipping out of the North, and with it the creatures of passage. On the last day of August, somewhere, monarch butterflies were on the move.\ Leaving western Washington for eastern, I noticed that the maritime greens had gone tired and blanched, ready for refreshment from the winter rains. Up on Swauk Pass, the first yellow among the serviceberry leaves rumored frost. That was where I had first seen and photographed a migrant monarch in Washington, twenty-five years before, as it sought nectar in a broad meadow near Blewett Summit. This afternoon the only butterflies on the wing were pine whites, flimsy pale drifters that fly at the end of summer and into the time of asters. Lake Chelan, the ancient glacial fjord in the heart of Washington's highlands, had gone gray from a light wind with the cold bit of autumn in its mouth. Dropping downlake out of the North Cascades, that wind suggested that any sensible butterfly would want to head south soon, if it had the means.\ But the next morning was bright and warming at Gallagher Flat, north of Chelan. I intended to begin following monarchs in Canada but to first search for signs of them on my way north. I was not alone at the start. My wife, Thea, set out with me, though she would return home before long, leaving me to make the chase solo. It was Thea, some years before, who had first found monarchs here. Chelan is among the richest and best-studied counties in the Northwest forbutterflies, and it is not easy to find something new within its borders. Thea, who used to live in Chelan, knew Gallagher Flat, a former embayment of the Columbia River, as an excellent site for wild asparagus. Noticing milkweed, she looked one fall for monarchs, and found them — the first recorded from the county. What better place to join these dances with monarchs?\ The old river channel lies between State Highway 97 on the east and a curving railroad line on the west, both built well up above the level of the frequently flooding bottoms. Across the roadway burbles the broad Columbia, dulled here now by Rocky Reach Dam. As we walked down onto the flat, we were surrounded by milkweed in various stages of maturation, from plants with soft, fuzzy little pods to those already bursting, seeding their down onto the air, as well as a single flower head still in fragrant pink bloom. A big Oregon swallowtail, the official state butterfly of Oregon, nectaring on a weedy purple vetch, rose, circled, and disappeared into an asparagus forest. This cheddar-yellow, black, and blue flier was the only other species likely to be seen here that is as big as a monarch, and it gave me a start. So did bright red grasshoppers. With my search image not yet calibrated, these flashes of color made potent false alarms. Yet when the real thing appeared, I knew it instantly.\ Recent years had not been strong for monarchs in the West. So when the first one showed up, around noon, I was both thrilled and relieved. There would be monarchs to follow! We were halfway up the length of the crescent-shaped flat on the river side. The monarch, too, nectared on the royal purple vetch, but a sturdy fence ran between us. Since it was my intention to catch, examine, and physically tag every monarch I could, in the slim hope that one or more might be recovered, I needed to get to it. I found a way through the tight-gauge wire, and then the monarch drifted like a feather, floated over the fence, and dropped onto the side I'd just come from. I shimmied through again, worked myself slowly into position for a wing shot, and swung. But I bricked it — one of the more polite collector's terms for missing a butterfly.\ The big orange beast powered up to the highway, then drifted back. I lost it against the crazy quilt of fall vegetation. Having noted its penchant for vetch nectar, I headed for a thick, tangled purple swale, and there it was. This was my first good, close look at a living monarch in months, and I savored it before taking a good, clear swing for what seemed a certain catch. But, hair-triggered, I struck short and bricked it again.\ The unsympathetic butterfly, a large, fresh male, was really disturbed this time. Before, it had flapped away from the source of menace in a leisurely way and resettled. Now it flew fast, high up toward the railroad tracks, then topped the bluff to the west, and, circling, disappeared into the clear sky at least a hundred yards above the ground. I saw right off the conflict between tagging and following, because in catching, or missing, I could scare them off. This one flew so high I was unable to get even a vanishing bearing, the direction of disappearance that enables observers to plot or follow an animal's movements.\ Still, something about missing my very first monarch seemed right. The Indians up and down the ruined Columbia, the Chinook and Yakama, Umatilla and Warm Springs, observed the rite of releasing the First Salmon of the season in thanks to the Salmon People for coming back. (This practice had many variations, and sometimes just its bones were sent back as emissary.) Of course, I was going to release the monarch anyway after I tagged it. But there is a tincture of enforced humility in missing that has to be salutary for a venture such as this. Pride is no friend to the wandering naturalist.\ I couldn't blame the miss on my butterfly net. Marsha's shaft is a five-foot cottonwood branch from the High Line Canal in Colorado. My brother Bud first found and used it as a walking staff. When I needed a new net pole one summer, I appropriated it, made a big hoop and bag for it, and named it for a strong friend. Donald Culross Peattie has written that the Omaha made sacred poles from cottonwoods, "the chief tree of the prairies" Marsha is my sacred pole. I have used her for more than twenty years now, and her skin is burnished from sweat, oil, and flesh. Heavier than most butterfly nets, Marsha is a two-handed tool. Though she was crooked, cracked, and liberally bound with duct tape, when I bricked a butterfly, it was almost never her fault.\ But even if this one had gotten away without a trace, I followed it anyhow in my mind. I could see it climbing the Entiat Valley into the Chumstick Mountains, down the other side and across the Wenatchee River, up again to Swauk Pass, where I had seen that lone traveler long ago. But then the route got blurry. I couldn't see where it went next.\ Thea and I rejoined at the far end of the flat, where hobos occasionally camped beneath cottonwoods. As we wandered back toward the car, barn swallows hunted insects over the sward, western kingbirds and meadowlarks screeched and fluted from the few vantages. For practice I stalked and netted Oregon swallowtails, taking care not to damage their long legs and tongues. Even the fresh ones often lacked one or both tails, having lost them to would-be insectivorous birds. When a kingbird targets the waving tails with their orange and blue highlights, rather than the boring-looking body, the tails are doing their job for the butterfly's survival.\ The place was full of butterflies. Little, bright orange mylitta crescents patrolled the pathways, darting out at purplish coppers the color of the vetch when the sun caught their prismatic scales just right. In truck ruts, where a little moisture remained, tawny skippers, buttery sulphurs, and cocoa wood nymphs puddled for salts. On the riverbank, a pair of Mormons were basking in the sun. Actually, they were Mormon metalmarks, very handsome rust, black, and white-checked butterflies, fall fliers and the only member of a vast group of tropical beauties that ranges up to the cold northern deserts.\ We saw no more monarchs until, driving north on 97, a few flashed by headed the other way. They seemed to be moving with the river, all right. Soon I would be following them south, but first I wanted to reach their northernmost breeding grounds in British Columbia. It was early enough, I hoped, that most of the migratory generation would still be caterpillars or chrysalides. They would metamorphose into adult butterflies and begin their migration in September. We were seeing the advance guard.\ At Pateros, where the wild Methow River gushes into the Columbia, we stopped at a fruit stand to buy late apricots and cherry cidersicles and to cast an eye over the milkweed around the mouth of the Methow. This stretch of the Columbia was once a major center for Northwest butterfly studies. Andy Anderson in Pateros and John Hopfinger in Brewster maintained important collections and traded specimens with lepidopterists from all over. They explored a great deal of unsampled territory in the North Cascades and Okanogan Highlands, places like Twisp Pass and the Sawtooth Range above Lake Chelan, and were the first to collect several far northern species south of the Canadian border. Specimens with their Brewster, Black Canyon, and Alta Lake locality labels found their way into museums all over the world.\ Hopfinger's and Anderson's records over more than half a century provide a window on the changes nature endured as the Columbia was altered. For example, in the early 1900s, Hopfinger found viceroy butterflies common all the way north to Brewster and beyond. Later, the inundation of riparian habitats by the Columbia dams drowned the viceroys' host plants and drove these butterflies up into the orchards. They were happy to feed on apple trees, but the heavy use of pesticides on the trees (little abated today) killed them off. Now viceroys can't be found nearly this far up the Columbia. Hopfinger and Anderson left no records for monarchs, however. It may be that milkweed, which spreads under some forms of human disturbance, has expanded upriver — and with it, breeding monarchs — even as the viceroys have withdrawn.\ Showy milkweed is common around Brewster now. Late in the day we walked the shoreline of Casimer Bar to the confluence of the Okanogan and Columbia rivers. Young Mexican men, fishing with poleless lines, looked askance at Marsha. Riparian plantings of alders and osiers, peachleaf and curly willows — a floristic mélange of local species and imported cultivars vaguely related to indigenous types -- show the restoration engineers' liberal definition of "native plants." Bright coppers shimmered in the pink knotweed, out of the wind. My broad canvas hat flew off into the marsh and I retrieved it with Marsha, another thing she's good for.\ We camped at Osoyoos Lake State Park next to Vladimir and Vera, Czech immigrants from Vancouver. I was struck by their given names, the same as those of the great novelist/lepidopterist Vladimir Nabokov and his wife. Nabokov, in his memoir Speak, Memory, expressed his amazement at how few people notice butterflies. My experience supports this and further suggests that of those who do, many refer to all large, colorful butterflies as "monarchs." Tiger swallowtails, in particular, are conflated with monarchs by the general public. Given the distinctive pattern of monarchs, this never ceases to surprise me. It speaks of people's vague awareness that big bright butterflies exist, the widespread familiarity of the name "monarch," and a desire to name the objects of the world even when knowledge lags way behind experience.\ Vlad and Vera eagerly told of a "carpet" of monarchs on the ground at a rest area south of Nelson in the Canadian Rockies, but I knew that Jon Shepard, a lepidopterist in Nelson who knows the British Columbian butterflies better than anyone else, had seen no monarchs there. This was the first of dozens of intriguing but certainly erroneous tips I would receive in the coming weeks. Vlad and Vera had seen a mess of swallowtails at mud, or tortoiseshells, or fritillaries. Still, they had noticed.\ As we curled into our sleeping bags, I thought again of the trip's first monarch, very fresh and richly colored, like burnt cinnamon and oranges. Easy to see at a distance, nectaring avidly on the purple vetch. I could have watched it for a long time, maybe followed it downriver until it was ready to fly on — though it might have stayed at Gallagher Flat all day or all week, tanking up for its long flight. I was sorry to drive it from the nectar fields. Such a fresh butterfly, so late in the summer, surely was a migrant. Any monarch emerging that late is subject to the dictate of day length to depart rather than mate. Wielding Marsha to no good effect, I might have sent it prematurely on its way to California or wherever it was bound; but it was probably ready to go. I wondered where and how it was spending this gusty last night of August.\ Did an Irishman really put the "0" on what had been Soyoos Lake, as the state park interpretive sign said? The name comes from an Indian word, sooyos, meaning narrows. But the sign also referred to the painted turtles in the lake as "amphibians," so I wasn't sure I wanted to trust it on the Irish issue. Another sign told of fecal coliform present in the park water system, so we drank some of the last of our good Gray's River water. Vlad and Vera chose to ignore the notice, taking the waters of Osoyoos liberally. As we packed up and parted, we wished them well, and meant it more than idly.\ Below the Canadian border, the Similkameen River flows from the west through a striking canyon. We followed it from Oroville to Shanker's Bend, then walked a rough track back along a canal that paralleled the river. An old homestead was now the headquarters of four species of woodpeckers: yellow-bellied sapsuckers and little downies worked the bank willows, while red-shafted flickers and a family of blue-blacked, rose-breasted Lewis's woodpeckers all hung around the old hardwoods. Downstream stood an antique dam with a waterfall, where men and kids fished from the rocks. Steel-hooped wooden pipes the old watermen call "galleries" rusted and rotted their way down the canyon. Across the river a trail, built on the old Union Pacific line, ran upstream. Lined with milkweed and goldenrod, the trail rounded the rugged canyon and dived into a dramatic tunnel. On our side, a fresh Lorquin's admiral dried its big, banded, apricottipped wings on a sagebrush. This close relative of the viceroy had come out just that morning.\ The tunnel emerged around a bend, pointing toward Nighthawk. Unwelcoming Nighthawk. From the cold stares and diffidence I have encountered there, I have sensed this tiny community with the beautiful name and remote location to be one of the least friendly in Washington. True, my first visit, several years earlier, may have been colored by the hordes of mosquitoes (suitably attended by nighthawks on the summer dusk). But this time the feeling was again palpable. No smiles, people disappearing around corners as we approached, no "Open" signs on the few businesses, and plenty of "No Trespassing" postings. Thea and I both felt it. Who can blame them, we agreed, with "Chopacka Estates" bulldozed out downstream and the thin edge of the cappuccino culture just a canyon away? Solitude like this is reluctantly surrendered. Garlands of wild hops draped themselves over ghost shacks with faded false fronts and sloping wooden stoops. This place too will change. I wanted to shout, Don't let it! The looks we got said, Just go away.\ Beyond Nighthawk the Similkameen broadens into Champney's Slough, a marshy bottomland with oxbows. Two-tailed tiger swallowtails and coronis fritillaries thronged the abundant asters. There was lots of milkweed, but no monarchs; I was beginning to realize that large orange migrants were not going to be omnipresent. Well, I told Thea, a surfeit at the outset has spoiled many an expedition, though I couldn't think of any examples offhand. She replied that there seemed little danger of that.\ The Similkameen River pours out of Canada. Rather than take the main road north from Nighthawk, I wanted to loop with the river and try a little boundary crossing that one of our maps showed farther west. The dirt road became a pair of ruts and stopped altogether at a fence well before the border. There was no entry station in sight. We lunched beneath Chopacka Mountain with a sheepdog who wandered by. The border collie (as, quite suitably, she was) begged bites. Together we watched a cheeky coyote trot over her field and across the international boundary, oblivious.\ Looking up at the gray mass of Chopacka, the easternmost massif of the Okanogan Highlands, I recalled the day a few summers before when I had climbed it. The trail rose stiffly from lodgepole pines into heather and finally to a stony dome of a summit. And there, on the very peak, I found Bean's arctic: a wisp of wing a little darker than the wind. That lichen-and-granite-matching butterfly of the satyr subfamily was one of the ones that John Hopfinger and Andy Anderson first collected in the States. As far from being a migrant as a butterfly gets, Oeneis melissa beani clings to the cirques and arêtes of the North Cascades in tight little colonies, going nowhere until glaciers or global warming push them off. Such conservatism, showing ultrafidelity to habitat and place, is the exact opposite of the strategy employed by monarchs. The one stays put, adapting itself to a harsh but relatively consistent regime; the other comes and goes, chasing the seasonal conditions that make its life possible.\ Whites coated the weedy mustards coming down from the border, and mourning cloaks, and the big Carolina grasshoppers whose black-and-yellow wings seem to mimic them leapt up from the dust as we drove past. At the shoreline village of Palmer Lake, a gorgeous garden beckoned, full of petunias, zinnias, and many other bright blooms, and spinning with colorful butterflies. I braked and hopped out. They turned out to be Leto fritillaries, the biggest orange butterflies in the region except for monarchs, and both Oregon and two-tailed swallowtails. All three species were swirling together in a fantastic tarantella, with an Oregon chasing a doubletail and the silverspot joining in.\ Folks were friendlier here than in Nighthawk, and why not? The people had found what they'd come for, retirement in a community of their own making. As the agents of change, they were happy with the outcome instead of ruing the future and the certainty of unwelcome change. The gardener's husband told me to feel free to look around and, true to form, referred to the whole show as monarchs. Farther south, in Loomis, the proprietor of the closed gas station cheerfully came straight from his television football game to give us a badly needed tankful. But when we returned to the border, it was back to scowls.\ The border crossing known as Nighthawk-Chopacka is a postcard scene, a pretty white cabin along a curving road into a broad vale. But the Crown Customs and Immigration officer, not particularly forthcoming -- brusque, even — did not reinforce the bucolic hospitality of the place. "We'll dispose of these;" he said, taking our Chelan apples and placing them well within his reach. He knew nothing of border-crossing butterflies and seemed almost affronted by the idea that they would do so without his permission. We didn't bring up the coyote. He finally waved us through, with a lingering look at our butterfly nets.\ Heading up the Canadian Similkameen, we kept an eye out for fruit stands to replenish our apple supply. At Mariposa Organic Garden -- mariposa means butterfly in Spanish — the proprietor, Lee, noticed my monarch T-shirt. She told me of a local family, the Mennells, who had something to do with monarchs. I watched an Oregon swallowtail dodging water drops on the lawn while Thea selected a melon, as the Mariposa was fresh out of apples.\ Down the road in Cawston, we called on the Mennells. Robert, bearded and not far from forty, and lively, brunette Jane, both in jeans and work shirts, welcomed us warmly. Like most of their neighbors, they farmed organically, growing apples, pears, apricots, peaches, nectarines, and melons. They had just suffered a near-injury accident when six bins of pears fell to the ground from a truck. Even so, they insisted we stay.\ They served us a fine dinner — their peppers and corn, our homegrown beans (the border guard didn't get them) — and fourteen-year-old Nicholas showed us his butterfly collection. He had done a splendid job of spreading them (better than I ever have, let alone at his age). I tried to impress upon him the need for punctilious labeling, a tedious business that raises a butterfly from a mere curio to a specimen of scientific value. For example, he had a beautiful white admiral — an eastern boreal butterfly of uncommon occurrence in western Canada, related to the viceroy and the Lorquin's admiral we'd seen that morning. Knowing it was from Conkle Lake, British Columbia, and the date of capture would make it a significant find; unlabeled, it could be from anywhere. I recalled trusting my memory at fourteen, too. I even remembered trusting my memory at forty.\ A little pink-and-gray kitten rolled around and batted from within a coiled map, as old cat Pansy came up to me for rubs. My own pussycat, Bokis, was not long gone after nineteen years, and I welcomed the attention. Jane showed us a photo of Nick's nine-year-old sister, blond Claire, with a big smile and great ball of banana slugs in her hands — "She loves `em," Jane said. Robert screened a long video of a monarch the family reared from a larva Nick had found in a nearby patch of milkweed. They had captured some excellent sequences of metamorphosis, as it grew and molted and transmuted from stripy caterpillar to jade chrysalis to flying butterfly. The release of the risen insect was clearly a major family occasion. I went to bed wishing that more young kids could be exposed to this kind of biophilia in their own homes.\ On September 2, Robert Mennell rose at dawn to pick nectarines at 45 degrees F. Later he would salvage the bruised pears, to sell at a loss for baby food. The rest of us rose somewhat later. After breakfast we crossed an orchard to a cabin near a fruit warehouse to visit Ron Loiseau, a Québecois seasonal worker for the Mennells and an amateur student of butterflies. His collection was beautifully maintained, and I saw where Nick had learned his good spreading technique. Ron, lanky and black-mustached, showed us a big female Leto fritillary. Our northwestern subspecies is sexually dimorphic to a dramatic degree, the female a large cheesecake-and-chocolate confection quite different from the fiery orange male and unlike the tawny female of the related great-spangled frits that Ron knew in Quebec. He thought she might be a Nokomis, a prized species of southwestern desert seeps, and I was sorry to disabuse him of the notion. Ron said he knew a good spot for monarchs and offered to guide us to it.\ Soon we were wading, dodging poison ivy, and kicking through knapweed on the Similkameen River dike beyond Cawston. The day was hot and humid, and my skin began to prickle. Nick and his younger brother, Chris, noticed feeding damage on milkweed leaves, and the little black barrels of caterpillar scat known as frass. Then he spotted a monarch larva browsing the edge of a floppy leaf. It was in its fifth and last instar, or molting stage, and thus not far from pupating. Spreading out along the shingle and the dike, we all began seeing monarchs at once, but we couldn't get to them — they were too far off, flying too fast, or across barriers of water or impenetrable vegetation. For the next hour, along the riverbank and through patches of milkweed, we ranged in the company of elusive monarchs.\ Thea and I were walking along the dike in the shade of tall cottonwoods, when Jane called from a field off to the east: "Here's one!" I spotted the orange flash, on again, off again, as it crossed the field and settled into the lush foliage. Scuttling to the site while trying not to scare it, I spied the monarch as it rose: a russet vision like a fox darting from its green covert. I took an easy wing shot and netted the great butterfly over fresh milkweed bloom.\ The monarch struggling in Marsha's diaphanous folds was a new female. Autumn emigrants are sexually immature and as a rule neither mate nor lay eggs until increasing day length the following spring triggers their hormones toward gonad development and mating. So she had only nectaring on her minute mind, and this she had been doing with fervor just before I caught her. Probably she had emerged only recently, perhaps maturing in this very milkweed patch or one nearby. But the milkweed's attraction for monarchs is not solely as the required caterpillar host plant. Showy milkweed, Asclepias speciosa, the only species in British Columbia, has thickly fragrant heads of florets like clusters of pale pink stars. Although happy to visit many kinds of flowers, monarchs take the nectar of their own host plants as avidly as any other.\ The others converged to see the beauty up close, as I withdrew her from the netting with flat-bladed stamp tongs. Then I tagged her so that she might tell us something more, later in her journey, if we were very lucky.\ Optimistically, I had brought along hundreds of tags in hopes of enlarging the sketchy western picture. My quarter-by-half-inch self-adhesive tags, like tiny mailing labels, came from the Northwest monarch study group known as One Thousand to One, based in Salem, Oregon. The one I now applied read like this:\ \ \ MAIL TO\ ENTOMOLOGY\ NAT HIST\ MUSEUM\ LOS ANGELES\ CA 90007\ MP-2\ 81726\ \ \ \ The final line is a serial number unique to each tag and thus to the butterfly tagged. When a recovery is made, just as with a banded bird, the tag establishes the data point showing that Monarch A traveled from Point B to Point C. Affixing the tag is a fairly simple procedure, but it takes practice and a firm hand. If you're afraid of hurting the butterfly, you may end up doing so or letting it get away. My personal technique involves holding the butterfly gently with my left hand, with the wings in closed position. I then grasp all four wings tightly near the base, with one forewing pulled up, the other pushed down. This is an easy position for the insect and does not hurt it. The wings are non-innervated chitinous material that can be handled gently without causing harm. Then, with thumb and forefinger, I rub the closed orange oval, or cell, bounded by black veins near the leading edge of one forewing to remove its scales. I used the left forewing, since most taggers use the right forewing and I wanted "my" butterflies easily distinguished from those tagged by others, especially if I should see them again.\ Now, common mother lore has it that you can kill butterflies, or render them unable to fly, by rubbing the "powder" off their wings. But the powder, the shinglelike scales that impart the colors, are shed throughout a butterfly's life. Removing scales causes no real physical harm, although a fully scaleless butterfly would not be able to advertise its identity or pattern defenses to other butterflies or predators, and might lack some ability to shed rain and slip out of spiderwebs. But I remove just one quarter of a square inch of scales on both the upper and under sides of the wing so that the label will adhere to the membrane on both sides. I tug the tag free from its backing sheet, bend it over the stiff leading edge of the wing (the costa), taking care not to crimp the wing, catch an antenna, or stick two wings together, and clamp it down. I record the sex, condition (this was a fresh female with a bird strike out of the right hindwing), and tag number.\ I released monarch #81726 onto laughing Claire's small nose. The butterfly paused just a second or two before her shining hazel-blue eyes, long enough for Claire to feel the tickle of the tarsi, before launching. Then the great insect rose, flew strongly off, and sailed over tall cottonwoods to the south.\ The Mennells told me that in 1992 there were hundreds or thousands of monarchs in their valley, with larvae on every milkweed. After that they seemed to collapse here, as in fact they had throughout the West. The summer of 1992 had also been the last time painted ladies invaded the North by the millions, only to die off in the fall. The monarchs appeared with the flood of painted ladies, even well into milkweedless western Washington, almost as if milkweed butterflies had been caught up in the massive parade of thistle butterflies. Painted ladies burst out of the Southwest and Mexico every few years, when the spring nectar runs heavy and weather conditions are propitious. In the spring of 1992, Interstate 5 was closed in southern California due to the immense influx. "Good" years for both migrants do not necessarily coincide as they did in 1992. But I can well imagine that roving monarchs might be virtually bowled along by the sheer numbers of smaller orange-and-black butterflies in such years. Now, four years later, neither species was abundant. But there in the broad meadows of milkweed and tall grass behind Rocking Chair Ranch, monarchs were on the wing in British Columbia.\ We took the larva back so Nick could rear, tag, and release it in ten days or a fortnight, along with any others they could catch. As we walked back, Ron spotted a huge Polyphemus moth larva, a fat applegreen serpent with silver embedded in bristled red spots along the spiracles, feeding on a willow. Then he pounced on a third-instar caterpillar of a western tiger swallowtail on a cottonwood sapling, its bogus snake-eyes pink and blue. Finally, he caught a big sesiid clearwing moth very much like the yellowjacket queens it mimics. Pearl crescents, like mini-monarchs, and big brown wood nymphs, like slow sparrows, respectively flap-glided and flip-flopped through the waist-high grass. Nick and Chris caught leeches in a backwater pond, ignoring the mosquitoes. Like all country kids, they had their own taxonomy for the critters they knew: mozzies, river frogs, red flickers (the red-winged grasshoppers that faked us out again and again).\ In the afternoon Thea and I pulled into Keremeos for supplies. At a rest area we watched a golden-tan satyr anglewing sipping at a urine patch in search of essential salts. It has made a completely different adaptation for surviving the Canadian winter. The monarch is probably the only species of butterfly that annually migrates into Canada in the spring and out again in the fall. Most butterflies get by in the egg, larval, or pupal stage, depending upon species. But the satyr anglewing, like half a dozen close relatives of the genera Polygonia and Nymphalis, hibernates as an adult butterfly through the harshest winters in a shed, bank, or tree cavity. Like the monarch, this one was tanking up on nutrients, but it was going nowhere. Heading upstream, we tanked up on the Mennells' nectarines.\ The broad pastures and milkweed valleys narrowed to a piny canyon. Just before the walls closed in, Thea spotted a monarch pendant from alfalfa in a field with milkweed beyond Stemwinder Provincial Park. The crazy traffic on Highway 3 headed to Vancouver for Canadian Labor Day kept us from getting back to find it. This was the limit of milkweed, the head of the Similkameen's portion of the monarch migration, at least as far as breeding goes.\ We took an early campsite on the south bank of the Similkameen, and slipped into the river's cool embrace under the looming presence of Bromley Rock. I held onto the shelf of a boulder and allowed the current to take me, like the sessile tadpole of a tailed frog. The polliwogs of that denizen of rapid mountain streams have suckers for holding fast to rocks so they don't drift away, and the adult males have a penis sheath in order to safely pass sperm in the current. As the sun dropped, the river grew still colder, and my own genitalia withdrew to about the stature of the tailed frog's equipment. My feet grew blue like the canyon's shadows. Then a mountain canyon campfire, the kind that calls for weenies & beans & beer. In the red flickers of the ponderosa flame I imagined monarchs rising into the night, flying off like sparks in the dark.\ \ \ Thea's forty-ninth birthday took us back down the Similkameen and up its tributary, the Ashnola River, checking milkweed. The Mennells had seen several monarchs up in the high lake country above Ashnola. Well beyond milkweed, they were likely summer arrivals from the south. Immigrants will fly until they die searching for mates and milkweed and thus often end up outside their potential breeding range.\ An impressively long, three-section, bright red covered bridge spanned the Similkameen near its confluence with the Ashnola. We live by the only remaining covered bridge in Washington, and we wanted to take a look at this one. Covered bridges were designed to protect the major truss beams from the elements. This type had no roof, but the side trusses were covered with siding inside and out, sandwich-style. Originally built for a railroad, it now carries cars. The Red Bridge, as it is named, is the northernmost location for the Mormon metalmark. But there were no butterflies at all about now, under the cool cloud cover.\ The history of monarchs in British Columbia is obscure, and some suggest that the migration may be a recent phenomenon there. That might explain the absence of monarchs from John Hopfinger's collection earlier in the century. But at the Keremeos Grist Mill, we found evidence that their host plants have been there for many years. The historic house near the restored mill had an exhibition of photographs and botanical illustrations by Julia Rachel Price Bullock-Webster, an Englishwoman who lived there around the turn of the century. Julia's diaries had three references to swallowtails, probably the Oregon, which closely resembles the British swallowtail she would have known, and she noted "red, brown, orange ones" visiting zinnias. She made no clear allusions to monarchs, and her delicate and deft botanical illustrations did not include milkweed. However, Thea spied milkweed in one of Mrs. Bullock-Webster's photographs. A scene of Keremeos's Main Street in 1910, it showed a foreground of solid Asclepias speciosa, with leaves and pods clearly visible. So we know that monarchs were not kept out of western Canada by an absence of host plants in those days.\ Later we explored stands of another plant that was long thought to be an alternative host for monarchs. We had crossed the watershed of the Similkameen, over Keremeos Creek, to the drier basin of interior British Columbia, and come to a place called Summerland. Neither sun nor summer was apparent. The mouth of Trout Creek was surrounded by brush, mostly Indian hemp, a waist- to chest-level, canelike herb with maroon stems and lemon-drop leaves in the fall. Apocynum sibericum (= cannabinum) is a type of dogbane used by many Native American groups for its fiber. The family Apocynaceae is closely related to the Asclepiadaceae (milkweeds); some dogbanes even produce a milky latex. Though Indian hemp has long been suspected to be a monarch food plant, recent studies by Susan Borkin in Wisconsin have shown it is not. Females may oviposit on it rarely, but larvae will starve rather than eat it. A single larva on Indian hemp in Utah is the only one I've heard about firsthand. Even so, the plant looked so much like milkweed that I couldn't help searching for monarchs. I didn't find any, but I did spot a brilliant picture-wing fly with a gemmed thorax; a striking yellow micro-moth; and a spotted prepupa in a shroudlike cocoon. There will always be interesting herbivores on any plant, if you look closely enough. "Brush" may be tedious when you're bushwhacking, but it is never boring.\ The gray day went cold, very autumnal, and a storm came up with thunder and heavy rain. Instead of camping, we went to ground in the Lakeshore Memories Bed and Breakfast, and instead of more hot dogs, we splurged on fresh halibut for Thea's birthday. The rain bucketed down that night. But we were warm and dry, and, unlike Fred Urquhart's first versions in the 1930s, the new monarch wing tags are waterproof.

Beginnings: Sky River11Similkameen112Okanogan283Grand Coulee434Crab575Columbia736Deschutes-John Day1017Hell's Canyon1188Snake1279Bear14510Bonneville15911Apache Gold18112Guadalupe19713Buenos Aires21014Cibola22315Pacifico23616Fandango253Endings: Recovery268AppConserving the Monarch of the Americas277Further Reading and Resources281Acknowledgments287Index291

\ Michiko Kakutani...Pyle chronicles his efforts to follow the monarchs on their winter migration by tracking them on the ground....By far the most absorbing portions...deal with Pyle's interaction with the monarchs...and his musings on their history and their habits....Pyle wants to believe "that there was a little more of something like freedom" built into a monarch's system..."\ — The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ America WestIf you enjoy the intellectual stimulus of traveling the footsteps of scientists, you'll like Robert Michael Pyle's Chasing Monarchs... Enthused by his enthusiasm, we come away with a heightened appreciation of the lives of birds and insects.\ \ \ Monarch News[Pyle's] delightful anecdotes, thought provoking philosophical questions and personal passion makes this chronicle a potential classic.\ \ \ \ \ Stewart KellermanOne-third memoir, one-third nature walk, one-third travelogue and one-third research paper — yes, four-thirds of a book....[W]hen he's not trying to out-Nabokov Nabokov, he can be quite moving, as in this description of female monarchs at the end of a northward migration... —The New York Times Book Review\ \ \ \ \ Publishers Weekly\ - Publisher's Weekly\ Scientists know that monarch butterflies migrate thousands of miles each year between northern parts of the U.S. and Mexico or California, but no one has actually seen how they do it. So ecologist Pyle Where Bigfoot Walks decided to try. His method: to find individual butterflies at their northernmost habitat, follow them as far as possible, then repeat the process with other individual butterflies along the southward route. Amazingly, this haphazard approach worked. Pyle began near the Canadian border, at the Columbia River, and followed monarchs to the Mexican border--covering 9462 miles in 57 days and proving that western monarchs do not all migrate to California, as commonly believed. Though Pyle's account of his rambling trip suggests that much of it must have been more fun to live through than to read about, he enlivens uneventful sections with butterfly arcana, humorous reminiscences and rueful observations on the environmental impact of cattle ranching, pesticides, dams and jet skis. Pyle's laid-back humor is appealing, his descriptive talents are often poetic he remembers monarchs pouring into a Mexican valley "like a heavy orange vapor" in which individuals resembled "flecks of foam and water as they top a waterfall and plunge down into the foaming mass". His memoir serves both as tribute to this majestic insect and as a thoughtful tour of the contemporary American West. Detailed sectional maps would have enhanced the book's appeal; endpaper map not seen by PW. Aug. FYI: Pyle is currently editing a collection of Vladimir Nabokov's butterfly writings. Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ KLIATTIn recent years, there has been a surge of interest in the monarch butterfly and its incredible journey of migration. Funds have been started to save some of its habitats and there has been concern about their depleting numbers. Author Robert Pyle, with a doctorate in ecology from Yale, has a scientist's view of the butterfly, but a writer's eloquence for expressing a great deal of information beautifully. He literally follows the monarchs south from British Colombia to Mexico and returns north along the California coast. This book is a wonderful merging of travelogue and scientific treatise. For anyone who marvels at the mystery of nature (how do they know where to travel?) and appreciates the expression of life in even its smaller representatives, this will be a joyful book. Writers like Robert Pyle, who make learning so easy, while remaining complete, are also a joy. For all public and academic libraries. Category: Nature & Ecology. KLIATT Codes: SA—Recommended for senior high school students, advanced students, and adults. 1999, Houghton Mifflin, Mariner, 307p. map. bibliog. index., Ages 16 to adult. Reviewer: Katherine E. Gillen; Libn., Luke AFB Lib., AZ\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalVictorian-era butterfly hunters are often portrayed as genteel aristocrats, but today's breed, like the author of this book, are gritty, adventurous, and far-wandering. Over two months and across 9000 miles, Pyle tracked and tagged monarch butterflies along their migratory route from northern British Columbia to Mexico. Because he is an ecologist, Pyle gives a solid general account of the state of scientific knowledge of the monarchs and their remarkable travels. Because he is also an award-winning natural history writer, he vividly conveys the lure of the butterflies, the quirky passions of those who study them, and the beauty and diversity of Western landscapes. Not only is this an entertaining work for general readers, but professional entomologists could also mine its observations for clues into the biology and behaviors of monarchs. For all libraries. [Previewed in Prepub Alert, LJ 4/15/99.]--Gregg Sapp, Univ. of Miami Lib., Coral Gables, FL Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Michiko Kakutani...Pyle chronicles his efforts to follow the monarchs on their winter migration by tracking them on the ground....By far the most absorbing portions...deal with Pyle's interaction with the monarchs...and his musings on their history and their habits....Pyle wants to believe "that there was a little more of something like freedom" built into a monarch's system..."\ — The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Stewart KellermanOne-third memoir, one-third nature walk, one-third travelogue and one-third research paper — yes, four-thirds of a book....[W]hen he's not trying to out-Nabokov Nabokov, he can be quite moving, as in this description of female monarchs at the end of a northward migration...\ — The New York Times Book Review\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsPyle (Where Bigfoot Walks: Crossing the Great Divide, 1995, etc.) takes a long, slow ramble with the wanderers, a.k.a. monarch butterflies, ostensibly looking for clues to their far-flung migratory behavior•but really just having a good time mooching around outdoors. That the monarch engages in the longest, most spectacular mass movement of insects is well known. It journeys from its continent-wide summertime diaspora to its astonishing winter be-ins high in the cool forests of Mexico and the coastal California fog belt. But, Pyle hastily points out, the theory needs some fine-tuning concerning which butterfly populations go to which wintering venue, and he thinks he ought to go look into the question. Thus starts his two-month sabbatical with the monarchs, chronicled here with an enviably laid-back demeanor and an unflagging thrill in simply being outside, walking attentively through the landscape. Monarchs may be his quarry, but seeing that there are precious few of them at the journey's start, up in British Columbia, Pyle is just as happy with the Mormon metalmarks and Arizona sisters and hackberry emperors, with yellowbelly ponderosa, partridges flushed from fields of peppermint, "a brilliant picture-wing fly with a gemmed thorax." As he does his easy shuffle to Mexico, he stops to have a good look around and sip a beer, serving as a natural and political historian; he keeps an eye peeled for monarchs on the move while delivering crisp, thoughtful lectures on protective coloration (for monarchs that means not camouflage, but a horn-blast of chromatic orange, reminding predators of their bitterness), orienteering with sun compasses and magnetic fields, or American Indianpetroglyphs that have been copyrighted as trademarks by upscale white resorts "in a stilling act of cultural appropriation." As for the monarchs, there do appear to be some transmontane migrants, a fact that runs counter to established thinking, although that will require further research. And say, isn't that a microbrewery over there? Natural history never went down easier. (Author tour)\ \