Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard

Apsley Cherry-Garrard was one of the youngest members of Robert Falcon Scott’s legendary expedition to Antarctica, the last man sent out to meet Captain Scott and his men in February 1912, when they were expected to return victorious any day from the South Pole. He embarked on his own epic journey into the Antarctic winter to collect eggs of the Emperor penguin. It was dark all the time, his teeth shattered, and the tent blew away in the cold. “But we kept our tempers,” he wrote, “even with...

Search in google:

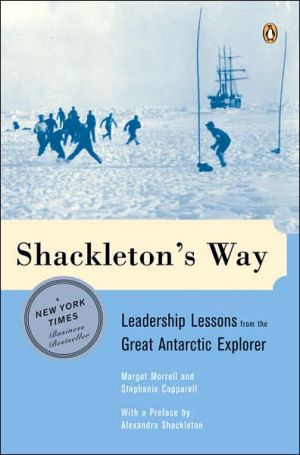

Apsley Cherry-Garrard was one of the youngest members of Robert Falcon Scott’s legendary expedition to Antarctica, the last man sent out to meet Captain Scott and his men in February 1912, when they were expected to return victorious any day from the South Pole. He embarked on his own epic journey into the Antarctic winter to collect eggs of the Emperor penguin. It was dark all the time, his teeth shattered, and the tent blew away in the cold. “But we kept our tempers,” he wrote, “even with God.”After serving in the First World War, with zealous encouragement from his neighbor George Bernard Shaw, Cherry wrote the undisputed masterpiece of polar literature, The Worst Journey in the World. But as the years progressed, he faced a terrible struggle against depression and despair. Sara Wheeler’s Cherry is the first biography of this great hero of Antarctic exploration, written with unrestricted access to his papers and with the full cooperation of his family. Publishers Weekly In a richly detailed and lyrical biography, Wheeler (Terra Incognito) traces the life of British adventurer Apsley Cherry-Garrard from his time as "a small boy with a lively imagination and a taste for snails and solitude" to his participation in Robert Scott's fateful 1911 expedition to reach the South Pole. While many have questioned and even vilified the members of Scott's voyage for everything from na vet to outright blundering, Wheeler takes a sympathetic, even reverent attitude toward her subject. Cherry-Garrard unfolds as a complicated figure whose youthful quest for adventure enmeshed him in an undertaking that towered over the rest of his life. While it would be hard for any historical account to rival Cherry-Garrard's own descriptions in his memoir The Worst Journey in the World, Wheeler tells the story of the entire voyage, whereas Cherry-Garrard focused on only one part of it. Though she quotes often from his book, the passages are complemented and occasionally contradicted by the journals of other members of the trip. In this way, Wheeler supplies the little facts that truly make her story vivid, like one explorer almost being killed by a 500-pound crate of hams propelled by a blizzard wind or another suggesting a can opener to cut through Cherry-Garrard's frozen clothes. Eloquent and gripping, Wheeler goes on to chronicle Cherry-Garrard's troubled homecoming and how, through writing his book and finding love late in life, the explorer made his ultimate discovery redemption. Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.

Chapter 1\ Ancestral Voices\ \ In the restless years of middle age Cherry used to sit in the bow-window of his library, turning the pages of the journals he had kept in the Antarctic three decades before. Absorbed in those far-off years, he jotted notes in the margins, as if the expedition had not yet reached its conclusion. ‘All Scott’s men had been altered,’ he wrote crossly. ‘Scott should have asked the doctors for their advice.’ Beyond the trimmed lawns outside, the familiar figure of Tilbury, the head gardener, stooped over the rhododendrons. The rooks returned to their nests in the elms, briefly darkening the sky. Cherry leafed through the flimsy notebook, recalling the rippled glaciers that tumbled down Mount Erebus, their gleaming cliffs casting long blue shadows; the crunching patter of dogs on the march; the pale, shadowless light of the ice shelf and a smudgy sun wreathed in mist. ‘Those first days of sledging were wonderful!’ he had written. In the quiet of his library he heard again the hiss of the Primus after a long, hard day on the trail, and smelt the homely infusion of tobacco as the night sun sieved through the green cambric of the tent. He tasted the tea flavored with burnt blubber, and felt the rush of relief as tiny point of light from the kippered hut glimmered faintly in the unforgiving darkness of an Antarctic winter. ‘Can we ever forget those days?’ he wrote.\ Cherry tortured himself over his action in February 1912, when he had driven a team of dogs 150 miles south to a foot depot to wait for Captain Scott and his four companions; they were expected to return from the Pole at any day. Winter was closing in and Cherry was navigating for the first time in his life, desperately handicapped by short sight, brutal temperatures and diminishing light. He reached the foot depot with his Russian dogdriver, and, following instructions, they stopped, pinned down in a tiny tent in hundreds of miles of opaque, swirling drift. They could not go on: they had no dog food to spare. Cherry remembered straining his eyes in the milky light of the Great Ice Barrier, looking for men who never came. One night he was so sure he could see figured approaching that he had reached for his boots and set out to meet them.\ The truth was that he could have gone on. He could have pressed on through the blizzard, killing a dog at a time to feed the others. He had been ordered to spare the dogs, but, as he had once written, ‘In this sort of life orders have to be elastic.’ If he had killed the dogs, and if he had journeyed just twelve-and-a-half miles further, there was a tiny chance that he might have stumbled on a small pyramid tent in which three men were dying. One was Captain Scott. The other two were Birdie Bowers and Bill Wilson, the closest friends Cherry had ever had. It was Bill who had got him onto the expedition; Bill who had stood in for his dead father; Bill who had taught him the things he came to think were most important. In death and in life, Bill as never far from Cherry’s mind. ‘If you simply knew him,” he wrote of his mentor, ‘you could not like him: you simply had to love him.’ When, having missed Scott and the others, he got back to the hut that was their Antarctic base, Cherry dreamt that his friends walked in. Almost two decades later he noted in the margin of his polar journal, ‘My relief was so intense that I can remember waking up to the disappointment even now.’\ Ten months after the journey to the food depot Cherry and a search party found the tent, piled with snow and weighted to the ice by three mottled corpses. He went through Bill’s pockets, collecting the contents for his widow. The body was hard, like stone. After prayers, they left the three men side by side in their sleeping bags, removing the bamboo tent poles and collapsing the cambric over them. The sun was dipping low over the Pole, the Barrier almost in shadow, and the sky was a mass of iridescent cloud, dark against gold and emerald. Cherry said it was a grave which kings must envy.\ From that day, he was obsessed by the thought that he might have saved them. ‘If we [he and the Russian dog-driver] had traveled on for a day and a half,’ he wrote, ‘We might have left some food and oil on one of the cairns, hoping that they would see it.’ It was a devastating realization. ‘But we never dreamed that they were in great want. It will always to the end of my life be a great sorrow to me that we did not do this.”

\ From Barnes & Noble"Cherry" was the nickname of Apsley Cherry-Garrard, the author of the exploration classic The Worst Journey in the World, about Robert Falcon Scott's unsuccessful -- and fatal -- attempt to reach the South Pole. For ten years, Cherry-Garrard tried to discover what went wrong for Scott and his fellow explorers, as documented in Sara Wheeler's fascinating biography.\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyIn a richly detailed and lyrical biography, Wheeler (Terra Incognito) traces the life of British adventurer Apsley Cherry-Garrard from his time as "a small boy with a lively imagination and a taste for snails and solitude" to his participation in Robert Scott's fateful 1911 expedition to reach the South Pole. While many have questioned and even vilified the members of Scott's voyage for everything from na vet to outright blundering, Wheeler takes a sympathetic, even reverent attitude toward her subject. Cherry-Garrard unfolds as a complicated figure whose youthful quest for adventure enmeshed him in an undertaking that towered over the rest of his life. While it would be hard for any historical account to rival Cherry-Garrard's own descriptions in his memoir The Worst Journey in the World, Wheeler tells the story of the entire voyage, whereas Cherry-Garrard focused on only one part of it. Though she quotes often from his book, the passages are complemented and occasionally contradicted by the journals of other members of the trip. In this way, Wheeler supplies the little facts that truly make her story vivid, like one explorer almost being killed by a 500-pound crate of hams propelled by a blizzard wind or another suggesting a can opener to cut through Cherry-Garrard's frozen clothes. Eloquent and gripping, Wheeler goes on to chronicle Cherry-Garrard's troubled homecoming and how, through writing his book and finding love late in life, the explorer made his ultimate discovery redemption. Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsA nimble and discerning biography of an aristocratic adventurer who wrote one of the finest books on polar exploration. Considering the adoration in which he is held in polar circles, it comes as a shock to learn that Wheeler's is the first biography of Cherry-Garrard. The explorer's Worst Journey in the World, chronicling his three years in the Antarctic with Robert Falcon Scott, is routinely cited as a peerless example of adventure-writing. And Wheeler (Terra Incognita, not reviewed, etc.) does a remarkable job in coaxing from scant primary source materials a sense of the man, presenting a personality to go with Cherry-Garrard's detached, ironic voice. He was privileged, as someone with a name like that must be, reared on great English estates with rooks and gardeners and manor houses old enough to have medieval architectural remnants. Though he was never comfortable with the swells and the bloods, he harbored a respect for tradition and ritual, and his "ambition, single-mindedness, and self-reliance" led him into the arms of Robert F. Scott and the push to the South Pole, with its disastrous consequences, for which Cherry-Garrard assumed his own share of the responsibility. Building on the reminiscences of Cherry-Garrard's widow, Wheeler fashions a convincing portrait of a man who rued the changes in the pastoral landscape and the position of the gentry and was deeply depressed by his many illnesses and the dreadful consequences of war, economic depression, then more war-all shaping a life that feels an extended exercise in "elegiac melancholy." Though she doesn't try to gloss the silences in the historic record, the author's image of Cherry-Garrard isn't fragmentary, but rather crazed, like an old mirror or the polar ice. Wheeler has set a high standard for Cherry-Garrard biographies to come, as surely they will. (16-page photo insert)\ \