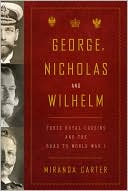

Churchill's Promised Land: Zionism and Statecraft

This book is the first to explore fully the role that Zionism played in the political thought of Winston Churchill. Michael Makovsky traces the development of Churchill’s positions toward Zionism from the period leading up to the First World War through his final years as prime minister in the 1950s. Setting Churchill’s attitudes toward Zionism within the context of his overall worldview as well as within the context of twentieth-century British diplomacy, Makovsky offers a unique...

Search in google:

A comprehensive examination of Churchill’s complex political, diplomatic, and intellectual response to Zionism

Churchill's Promised Land\ ZIONISM AND STATECRAFT \ \ By MICHAEL MAKOVSKY \ YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS\ Copyright © 2007 Yale University\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-300-11609-0 \ \ \ Chapter One\ Churchill's Worlds \ IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO GAIN PROPER insight into a person's views on a subject without understanding that person's overall worldview. This is certainly true when examining Winston Churchill's approach toward any world issue, but especially Zionism, a relatively new issue that did not have much relevance to British imperial or strategic interests. More than most politicians and statesmen, Churchill often appeared erratic in his opinions, and yet in truth he developed a distinct perspective of the world.\ Although he is perceived today by many, particularly in the United States, as a man of great principles and constancy, for much of his life and even after his death Churchill's convictions were often questioned and his positions considered functions of ill judgment and political opportunism. Shortly before the First World War, by which time Churchill had served in Parliament and government for more than a decade, the discerning journalist A. G. Gardiner reflected a widespread view of his fellow Liberal: "It is the ultimate Churchill that escapes us." Churchill was a "soldier" who "loves the fight more than the cause"; "whatever shrine he worshipsat, he will be the most fervid in his prayers." Indeed, during much of his career, especially early on, Churchill directed fierce rhetoric against whatever, whichever, or whomever was his enemy at the time. Contributing to the confusion over Churchill's core character was his shifting political allegiance, which switched from the Conservative Party to the Liberal Party in 1904, then to a center party in the early 1920s that never fully materialized, and then back again to the Conservative Party in 1924. All told, he was affiliated with the Conservative Party for thirty-five of his fifty-five years in active politics, but he was never completely accepted by it. His pedigree further muddled matters. His father, Randolph, came from a distinguished aristocratic family descended from the famous Duke of Marlborough, but Randolph was a distrusted maverick in the Conservative Party, and his audacious, meteoric political career ended abruptly. Churchill's mother, Jenny Jerome, was American, and many British observers considered that a significant flaw in Churchill's character. As late as 1940, Churchill, upon becoming prime minister at the age of sixty-five, was referred to by one Conservative politician as a "half-breed American." Many attributed to him American characteristics, such as overt ambitiousness, interest in money, hyperactivity, brashness, and capriciousness. These qualities, especially in a youth, were unacceptable to the stuffy, old-fashioned, inflexible, wealthy Conservative establishment. As the socialist dramatist George Bernard Shaw put it to Churchill in 1946: "You [are] a phenomenon that the Blimps and Philistines and Stick-in-the-muds have never understood and always dreaded." Churchill also did not fit in well in the period in which he lived. In 1898, the journalist G. W. Steevens described him at twenty-four years old to be the "youngest man in Europe" who had "the twentieth century in his marrow." Yet, decades later, it was widely believed that Churchill was stuck in the nineteenth century.\ Churchill did not belong only to one period, nor can his character be easily classified, especially not by the standards of the rigid, stratified British society of his lifetime. He had a complex world outlook that blended realism, sentimentalism, Victorianism, Edwardianism, Liberalism, Conservatism, and other credos. He essentially lived in three worlds, defined by the periods 1814-1913, 1914-1939, and 1940-1955. The first world, 1814-1913, was his favorite. It was this period that shaped his core principles, aspirations, strategic vision, and image of British power and prestige. The second world, 1914-1939, his least favorite, was a corruption of the first. The third world, 1940-1955, was a sort of hybrid, offering great promise before it too degenerated. Churchill worked to achieve the aspirations of the first world by applying the principles and values of that era to the realities of the second and third worlds. He sought guidance from history but shirked the stultified embrace of the past of some Conservatives. He avoided the love of newness for its own sake that characterized some Socialists, yet he often nimbly recognized and embraced new developments, such as scientific advancements, the rise of the United States, and Zionism. Steeped in the past, Churchill nevertheless always concentrated on the present and the future, which often put him at odds with public opinion. Churchill also remained fixated on his supreme priorities, such as British strategic and imperial interests and at certain times his own political goals. For someone with varied and complex world interests, this meant that his romantic and sentimental concerns frequently took a backseat to these primary objectives, except when they were aligned. Such certainly was the case with his approach toward Zionism, a sentimental cause that evolved into an important part of his worldview but always remained a subordinate issue for him. Thus, only with some fundamental understanding of how he looked at each of his three distinct worlds can we understand what he cared about and how Zionism fit in.\ Throughout his life Churchill looked at the period dating roughly from the Congress of Vienna (1814-1815), which followed the end of the Napoleonic wars, to the start of the First World War (1914) as a golden age for Britain and the world. He embraced this era, which can be labeled the Victorian period since it was mostly marked by the reign of Queen Victoria (1837-1901). It became a "vanished age" to which he always compared subsequent eras. He regarded it as a period dominated by Great Britain and Europe, and marked by optimism, civility, grand statesmen, Great Powers, peace, stability, honor, romanticism, patriotism, and the relentless progress of civilization. In 1921, reflecting the national nostalgia for the Victorian period during the interwar years, he wrote shortly after his mother's death, "The old brilliant world in which she moved and in wh [which] you met her is a long way off now, & we do not see its like today." And in 1937 he claimed that future British generations would view the Victorian era "with the same wistful and wondering regard that the later Romans cast upon the Age of the Antonines." Even his nostalgia for the period was invoked in a Victorian manner, as the late Victorians often compared their age to the Roman era.\ The Victorian period was, Churchill wrote, one of "triumphant serenity," when the British Empire was unrivaled in global reach and power. He argued that the empire was a slowly built inheritance that should remain the size it was under Queen Victoria, no larger and no smaller, though its form might change. It was a fixed "monument" to Britain's historical and present grandeur. He deeply felt that this era was a time when civilization was continually on the march, a view widely shared among late Victorians, and considered the empire an essential instrument of that progress. Many Britons in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries justified their imperial rule with their civilizing mission. For Churchill, it was no mere rationalization. He firmly believed that Britain, within limits, had an obligation to "civilize" those peoples deemed backward. In 1897, weeks after Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee, he concluded his maiden public speech-at the Primrose League, founded by his father in honor of Benjamin Disraeli, the late-nineteenth-century Conservative leader whose romantic imperial view Churchill shared-by arguing against those "croakers" who thought the empire had peaked. Instead, he advocated continued vigor in maintaining the empire by which Britain carried out "our mission of bearing peace, civilisation and good government to the uttermost ends of the earth." In his 1899 book on the Sudan war, he relayed how Britain helped civilize alleged backward peoples: "What enterprise that an enlightened community may attempt is more noble and more profitable than the reclamation from barbarism of fertile regions and large populations? To give peace to warring tribes, to administer justice where all was violence, to strike the chains off the slave, to draw the richness from the soil, to plant the earliest seeds of commerce and learning, to increase in whole peoples their capacities for pleasure and diminish their chances of pain-what more beautiful ideal or more valuable reward can inspire human effort?" Exuding an almost limitless faith in Britain's role in the advance of civilization, he spoke in 1908 of pet plans for the development of British East Africa, which he had visited six months earlier as colonial under-secretary: "The work of civilization is going on." In that position, he took Britain's civilizing responsibility very seriously. His minute in 1906 on a seemingly petty issue in Ceylon was indicative: "Our duty is to insist that the principles of justice and the safeguards of judicial procedure are rigidly, punctiliously and pedantically followed."\ Race was integral to this world, though the focus on it was becoming increasingly disreputable in English society. Churchill conceived a hierarchy of races and civilizations, where the top-tier races had much to contribute to those on the bottom rungs. The British, their Teutonic cousins the Germans, their Anglo-Saxon brethren the Americans, and the Gaullist French were at the top of this racial totem pole. The Jews were in either this rung or the one below, and the Russians were much lower, along with other backward, despotic, and barbaric "Asiatics." Below the Russians were the Arabs, and below them the tribes of Africa and India. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, Churchill thought a good deal about race when he encountered Indians, Sudanese, and East Africans as a soldier and then as colonial under-secretary. He described these people as hardly superior to animals, using such terms as "barbarous" (Indian tribes), "simple-minded savages" (indigenous Sudanese), "debased and cruel breed" (Arab-Sudanese), "warlike" and "wild" (Arabs), and "filthy Oriental" (Turks). He felt that these races held back the advance of civilization. Many of these people followed Islam, and he wrote in 1899 that he considered the religion a retrogressive force: "How dreadful are the curses which Mohammedanism lays on its votaries! Besides the fanatical frenzy ... there is this fearful fatalistic apathy ... improvident habits, slovenly systems of agriculture, sluggish methods of commerce ... wherever the followers of the Prophet rule or live.... Individual Moslems may show splendid qualities, but the influence of the religion paralyses the social development of those who follow it. No stronger retrograde force exists in the world." Even decades later he voiced such thoughts and used such language, and remained convinced of Anglo-Saxon superiority. This was common language at the time in England, which was historically a racially conscious country and was overwhelmingly white for much of Churchill's life. (Churchill in his youth also condescended to the lower socioeconomic rungs of white British society, although in less harsh terms, and as home secretary in 1910-1911 he became interested in the popular movement of eugenics, which favored sterilizing the "unfit" and maintaining "strength" in the English race.) No matter where a race stood on the totem pole, it had an obligation to advance civilization in whatever form or means possible. As he wrote in a 1908 book, "The Asiatic, and here I also include the African native, has immense services to render and energies to contribute to the happiness and material progress of the world." He insisted that everyone, from the superior Briton to the lowly African, shared this imperative, that "no man has a right to be idle, whoever he be or wherever he lives. He is bound to go forward and take an honest share in the general work of the world."\ Scientific advancement contributed to the progress of civilization in the Victorian period. Churchill was captivated by technological developments and participated in them. Although he grew up in the traditional arms of British imperial power-serving in the cavalry and becoming first lord of the Admiralty at a young age-he was so fascinated by the airplane and air power that he flew 140 times before the First World War and nearly received his pilot's license. He pushed development of the tank in the First World War and atomic power in the Second World War. He saw moral progress as underpinning scientific advances. Another factor in the progress of the age was the prevalence of grand statesmen such as Napoleon, Disraeli, and Liberal leader William E. Gladstone. Churchill remarked about the powerful men his father entertained that "it seemed a very great world in which these men lived," where they grappled with eminent matters.\ The man from this world whom Churchill revered the most was his father, Randolph, whose career he sought to vindicate. At a young age Churchill closely followed his father's speeches. He wrote later, "For years I had read every word he spoke and what the newspapers said about him." And the newspapers were very interested in Randolph's utterances. At sixty, Churchill wrote that after his father died (when Churchill was only twenty years old), "All my dreams of comradeship with him, of entering Parliament at his side or in his support, were ended. There remained for me only to pursue his aims, and vindicate his memory. This I have tried to do." He did so very deliberately, especially early in adulthood and his career. Churchill joined the Primrose League, which his father founded, and delivered his maiden political speech there at the age of twenty-two. When he crossed the aisle and left the Conservative Party in 1904 to join the Liberals, he notably sat down in the seat where his father had resided while in Opposition. Perhaps Churchill's grandest early act of fealty to his father was writing a fawning biography of him, though it also served some immediate political needs. Churchill sought his father's approbation throughout his life, even after the Second World War when he was old and had established himself as a legendary British and Western statesman. This was strikingly evident from a vision Churchill had in 1947 of an imaginary conversation with his father, who had been dead for more than fifty years and had apparently not had access to newspapers from the grave. The daydream was so vivid that he wrote it down. After explaining to Randolph how the world had changed since the late nineteenth century without mentioning his own role in global developments, Churchill envisioned his father replying, "As I listened to you unfolding these fearful facts you seemed to know a great deal about them. I never expected that you would develop so far and so fully. Of course you are too old now to think about such things, but when I hear you talk I really wonder you didn't go into politics. You might have done a lot to help. You might even have made a name for yourself." Randolph then showed a "benignant smile," lit a match for his cigarette, and vanished. Churchill finally managed to impress his father, but he clearly was pained that his father never knew all that he had accomplished. That was one achievement that forever eluded him.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Churchill's Promised Land by MICHAEL MAKOVSKY Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Preface ixAcknowledgments xiiiIntroduction 1Churchill's Worlds 9"The Lord Deals with the Nations as the Nations Dealt with the Jews," 1874-1914 38"Zionism versus Bolshevism," 1914-1921 69"Smiling Orchards," 1921-1929 98Together in the Wilderness, 1929-1939 140Champion in War, 1939-1945 171Zionist at the End, 1945-1955 227Conclusion 259Notes 267Bibliography 299Index 323