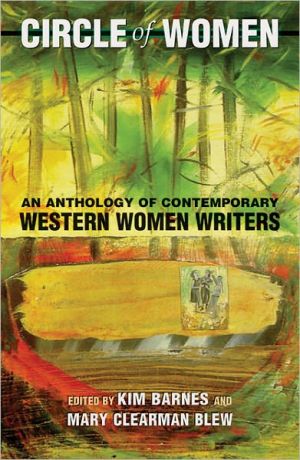

Circle of Women: An Anthology of Contemporary Western Women Writers

This striking array of stories, essays, and poems reflects women’s experiences in the American West. Though the tales they tell reflect a variety of viewpoints, these writers share the struggle against the overwhelming isolation brought on by gender and the physical environment.\ Contributors include:Christina Adam, Gretel Ehrlich, Anita Endrezze, Tess Gallagher, Molly Gloss, Pam Houston, Teresa Jordan, Cyra McFadden, Deirdre McNamer, Melanie Rae Thon, Marilynne Robinson, Annick Smith, Terry...

Search in google:

This striking array of stories, essays, and poems reflects women's experiences in the American West. Though the tales they tell reflect a variety of viewpoints, these writers share the struggle against the overwhelming isolation brought on by gender and the physical environment.Publishers WeeklyThrough poems, essays and stories from 35 contributors, readers can travel into a world of rodeos, saloons, canyons, sagebrush, isolation and wilderness, immersing themselves, like the narrator in editor Blew's piece, ``bone-deep in landscape.'' What Teresa Jordan calls the ``interior'' or ``hidden stories'' of family, loneliness and emotional trial have been largely passed over by traditional male Western storytellers, but this collection offers insight into more intimate epics like Jordan's story of an Indian girl and her father, an ex-convict unable to make a life for himself off the reservation, who teaches her to make her life ``her own.'' The collection starts with Blew's nostalgic blurring of dream and memory but ends with Terry Tempest Williams's ``The Clan of One-Breasted Women'' about a Utah Mormon who discovers that the flash of light she thought was a dream was a real nuclear explosion and breaks with conservative tradition by questioning authority when her mother, both grandmothers and six aunts develop breast cancer. Although there are flawed contributions, this evocative collection with works by Tess Gallagher, Melanie Rae Thon, Anita Endrezze, Gretel Ehrlich, Cyra McFadden and others, coheres in examining Western myths and traditions through the lives of women. (July)

\ \ Chapter One\ \ \ Mary Clearman Blew\ The Sow in the River\ \ \ In the sagebrush to the north of the mountains in central Montana, where the Judith River deepens its channel and threads a slow, treacherous current between the cutbanks, a cottonwood log house still stands. It is in sight of the highway, about a mile downriver on a gravel road. From where I have turned off and stopped my car on the sunlit shoulder of the highway, I can see the house, a distant and solitary dark interruption of the sagebrush. I can even see the lone box elder tree, a dusty green shade over what used to be the yard.\ I know from experience that if I were to keep driving over the cattle guard and follow the gravel road through the sage and alkali to the log house, I would find the windows gone and the door sagging and the floor rotting away. But from here the house looks hardly changed from the summer of my earliest memories, the summer before I was three, when I lived in that log house on the lower Judith with my mother and father and grandmother and my grandmother's boyfriend, Bill.\ My memories seem to me as treacherous as the river. Is it possible, sitting here on this dry shoulder of a secondary highway in the middle of Montana where the brittle weeds of August scratch at the sides of the car, watching the narrow blue Judith take its time to thread and wind through the bluffs on its way to a distant northern blur, to believe in anything but today? The past eases away with the current. I cannot watch a single drop of water out of sight. How can I trust memory, which slips and wobbles and grinds its erratic furrows like a bald-tired truck fighting for traction on a wet gumbo road?\ \ \ * * *\ \ \ Light flickers. A kerosene lamp in the middle of the table has driven the shadows back into the corners of the kitchen. Faces and hands emerge in a circle. Bill has brought apples from the box in the dark closet. The coil of peel follows his pocketknife. I bite into the piece of quartered apple he hands me. I hear its snap, taste the juice. The shadows hold threats: mice and the shape of nameless things. But in the circle around the lamp, in the certainty of apples, I am safe.\ The last of the kerosene tilts and glitters around the wick. I cower behind Grammy on the stairs, but she boldly walks into the shadows, which reel and retreat from her and her lamp. In her bedroom the window reflects large pale her and timorous me. She undresses herself, undresses me; she piles my pants and stockings on the chair with her dress and corset. After she uses it, her pot is warm for me. Her bed is cold, then warm. I burrow against her back and smell the smoke from the wick she has pinched out. Bill blows his nose from his bedroom on the other side of the landing. Beyond the eaves the shapeless creatures of sound, owls and coyotes, have taken the night. But I am here, safe in the center.\ I am in the center again on the day we look for Bill's pigs. I am sitting between him and Grammy in the cab of the old Ford truck while the rain sheets on the windshield. Bill found the pigpen gate open when he went to feed the pigs this morning, their pen empty, and now they are nowhere to be found. He has driven and driven through the sagebrush and around the gulches, peering out through the endless gray rain as the truck spins and growls on the gumbo in low gear. But no pigs. He and Grammy do not speak. The cab is cold, but I am bundled well between them with my feet on the clammy assortment of tools and nails and chains on the floorboards and my nose just dashboard level, and I am at home with the smell of wet wool and metal and the feel of a broken spring in the seat.\ But now Bill tramps on the brakes, and he and Grammy and I gaze through the streaming windshield at the river. The Judith has risen up its cutbanks, and its angry gray current races the rain. I have never seen such a Judith, such a tumult of water. But what transfixes me and Grammy and Bill behind our teeming glass is not the ruthless condition of the river—no, for on a bare air at midcurrent, completely surrounded and only inches above that muddy roiling water, huddle the pigs.\ The flat top of the ait is so small that the old sow takes up most of it by herself. The river divides and rushes around her, rising, practically at her hooves. Surrounding her, trying to crawl under her, snorting in apprehension at the water, are her little pigs. Watching spellbound from the cab of the truck, I can feel their small terrified rumps burrowing against her sides, drawing warmth from her center even as more dirt crumbles under their hooves. My surge of understanding arcs across the current, and my flesh shrivels in the icy sheets of rain. Like the pigs I cringe at the roar of the river, although behind the insulated walls of the cab I can hear and feel nothing. I am in my center and they are in theirs. The current separates us irrevocably, and suddenly I understand that my center is as precarious as theirs, that the chill metal cab of the old truck is almost as fragile as their ring of crumbling sod.\ And then the scene darkens and I see no more.\ \ \ * * *\ \ \ For years I would watch for the ait. When I was five my family moved, but I learned to snatch a glimpse whenever we drove past our old turnoff on the road from Lewistown to Denton. The ait was in plain view, just a hundred yards downriver from the highway, as it is today. Ait was a fancy word I learned afterward. It was a fifteen-foot-high steep-sided, flat-topped pinnacle of dirt left standing in the bed of the river after years of wind and water erosion. And I never caught sight of it without the same small thrill of memory: that's where the pigs were.\ One day I said it out loud. I was grown by then. "That's where the pigs were."\ My father was driving. We would have crossed the Judith River bridge, and I would have turned my head to keep sight of the ait and the lazy blue threads of water around the sandbars.\ My father said, "What pigs?"\ "The old sow and her pigs," I said, surprised. "The time the river flooded. I remember how the water rose right up to their feet."\ My father said, "The Judith never got that high, and there never was any pigs up there."\ "Yes there were! I remember!" I could see the little pigs as clearly as I could see my father, and I could remember exactly how my own skin had shriveled as they cringed back from the water and butted the sow for cold comfort.\ My father shook his head. "How did you think pigs would get up there?" he asked.\ Of course they couldn't.\ His logic settled on me like an awakening in ordinary daylight. Of course a sow could not lead nine or ten suckling pigs up those sheer fifteen-foot crumbling dirt sides, even for fear of their lives. And why, after all, would pigs even try to scramble to the top of such a precarious perch when they could escape a cloudburst by following any one of the cattle trails or deer trails that webbed the cutbanks on both sides of the river?\ Had there been a cloudburst at all? Had there been pigs?\ No, my father repeated. The Judith had never flooded anywhere near that high in our time. Bill Hafer had always raised a few pigs when we lived down there on the river, but he kept them penned up. No.\ \ \ * * *\ \ \ Today I lean on the open window of my car and yawn and listen to the sounds of late summer. The snapping of grasshoppers. Another car approaching on the highway, roaring past my shoulder of the road, then fading away until I can hear the faint scratches of some small hidden creature in the weeds. I am bone-deep in landscape. In this dome of sky and river and undeflected sunlight, in this illusion of timelessness, I can almost feel my body, blood, and breath in the broken line of the bluffs and the pervasive scent of ripening sweet clover and dust, almost feel the sagging fence line of ancient cedar posts stapled across my vitals.\ The only shade in sight is across the river where box elders lean over a low white frame house with a big modern house trailer parked behind it. Downstream, far away, a man works along a ditch. I think he might be the husband of a second cousin of mine who still lives on her old family place. My cousins wouldn't know me if they stopped and asked me what I was doing here.\ Across the highway, a trace of a road leads through a barbed-wire gate and sharply up the bluff. It is the old cutoff to Danvers, a town that has dried up and blown away. I have heard that the cutoff has washed out, further up the river, but down here it still holds a little bleached gravel. Almost as though my father might turn off in his battered truck at fifteen miles an hour, careful of his bald wartime tires, while I lie on the seat with my head on his thigh and take my nap. Almost as though at the end of that road will be the two grain elevators pointing sharply out of the hazy olives and ochers of the grass into the rolling cumulus, and two or three graveled streets with traffic moving past the pool hall and post office and dug-out store where, when I wake from my nap and scramble down from the high seat of the truck, Old Man Longin will be waiting behind his single glass display case with my precious wartime candy bar.\ Yes, that little girl was me, I guess. A three-year-old standing on the unswept board floor, looking up at rows of canned goods on shelves that were nailed against the logs in the 1880s, when Montana was still a territory. The dust smelled the same to her as it does to me now.\ Across the river, that low white frame house where my cousin still lives is the old Sample place. Ninety years ago a man named Sample fell in love with a woman named Carrie. Further up the bottom—you can't see it from here because of the cottonwoods—stands Carrie's deserted house in what used to be a fenced yard. Forty years ago Carrie's house was full of three generations of her family, and the yard was full of cousins at play. Sixty years ago the young man who would be my father rode on horseback down that long hill to Carrie's house, and Sample said to Carrie, Did your brother Albert ever have a son? From the way the kid sits his horse, he must be your brother's son.\ Or so the story goes. Sample was murdered. Carrie died in her sleep. My father died of exposure.\ \ \ * * *\ \ \ The Judith winds toward its mouth. Its current seems hardly to move. Seeing it in August, so blue and unhurried, it is difficult to believe how many drownings or near drownings the Judith has counted over the years. To a stranger it surely must look insignificant, hardly worth calling a river.\ In 1805 the explorers Lewis and Clark, pausing in their quest for the Pacific, saw the mountains and the prairies of central Montana and the wild game beyond reckoning. They also noted this river, which they named after a girl. Lewis and Clark were the first white recorders of this place. In recording it, they altered it. However indifferent to the historical record, those who see this river and hear its name, Judith, see it in a slightly different way because Lewis and Clark saw it and wrote about it.\ In naming the river, Lewis and Clark claimed it for a system of governance that required a wrenching of the fundamental connections between landscape and its inhabitants. This particular drab sagebrush pocket of the West was never, perhaps, holy ground. None of the landmarks here is invested with the significance of the sacred buttes to the north. For the Indian tribes that hunted here, central Montana must have been commonplace, a familiar stretch of their lives, a place to ride and breathe and be alive.\ But even this drab pocket is now a part of the history of the West, which, through a hundred and fifty years of white settlement and economic development, of rapid depletion of water and coal and timber and topsoil, of dependence upon military escalation and federal subsidies, has been a history of the transformation of landscape from a place to be alive in into a place to own. This is a transformation that breaks connections, that holds little in common. My deepest associations with this sunlit river are private. Without a connection between outer and inner landscape, I cannot tell my father what I saw. "There never was a sow in the river," he said, embarrassed at my notion. And yet I know there was a sow in the river.\ \ \ * * *\ \ \ All who come and go bring along their own context, leave their mark, however faint. If the driver glanced out the window of that car that just roared past, what did he see? Tidy irrigated alfalfa fields, a small green respite from the dryland miles? That foreshortened man who works along the ditch, does he straighten his back from his labors and see his debts spread out in irrigation pipes and electric pumps?\ It occurs to me that I dreamed the sow in the river at a time when I was too young to sort out dreams from daylight reality or to question why they should be sorted out and dismissed. As I think about it, the episode does contain some of the characteristics of a dream. That futile, endless, convoluted search in the rain, for example. The absence of sound in the cab of the truck, and the paralysis of the onlookers on the brink of that churning current. For now that I know she never existed outside my imagination, I think I do recognize that sow on her slippery pinnacle.\ Memory lights upon a dream as readily as an external event, upon a set of rusty irrigation pipes and a historian's carefully detailed context through which she recalls the collective memory of the past. As memory saves, discards, retrieves, fails to retrieve, its logic may well be analogous to the river's inexorable search for the lowest ground. The trivial and the profound roll like leaves to the surface. Every ripple is suspect.\ Today the Judith River spreads out in the full sunlight of August, oblivious of me and my precious associations, indifferent to the emotional context I have framed it with. My memory seems less a record of landscape and event than a superimposition upon what otherwise would continue to flow, leaf out, or crumble according to its lot. What I remember is far less trustworthy than the story I tell about it. The possibility for connection lies in story.\ Whether or not I dreamed her, the sow in the river is my story. She is what I have saved, up there on her pinnacle where the river roils.\ \ \ Excerpted from Circle of Women by . Copyright © 1994 by Mary Clearman Blew and Kim Barnes. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. \ \ \ \

IntroductionThe Sow in the River1Woodcutting on Lost Mountain10The Secret of Cartwheels17Iona Moon35When I Was Ten, at Night53Luck54The Just Rewards56Changing58From Housekeeping62Rules74Songs Were Horses I Rode78They Keep Their Story79For Mary, on the Snake80Visiting the Hutterites83Scale101From Missing You103From The Jailing of Cecelia Capture108In the Hellgate Wind133The Difference in Effects of Temperature Depending on Geographical Location East or West of the Continental Divide: A Letter135It's Come to This137From The Jump-Off Creek158Bones168Leaving Home180What Comes of Winter181At the Stockman Bar, Where the Men Fall in Love, and the Women Just Fall183From Rain or Shine: A Family Memoir186Entering Smoot, Wyoming Pop. 239197Seasons199Cry212Tracks214The Sawyer's Wife215Fires219In My Next Life242Red Rock Ceremonies258Claiming Lives259Moving Day at the Widow Cain's262Island264The Force of One Voice268Legend in a Small Town269From Relative Distances271The Other Side of Fire278A Coyote Is Loping Across the Water300The Hunsaker Blood315How I Came West, and Why I Stayed326From Rima in the Weeds341Circle of Women356Calling the Coyotes In358The Smell of Rain359The Clan of One-Breasted Women362Notes on the Contributors373

\ Publishers Weekly\ - Publisher's Weekly\ Through poems, essays and stories from 35 contributors, readers can travel into a world of rodeos, saloons, canyons, sagebrush, isolation and wilderness, immersing themselves, like the narrator in editor Blew's piece, ``bone-deep in landscape.'' What Teresa Jordan calls the ``interior'' or ``hidden stories'' of family, loneliness and emotional trial have been largely passed over by traditional male Western storytellers, but this collection offers insight into more intimate epics like Jordan's story of an Indian girl and her father, an ex-convict unable to make a life for himself off the reservation, who teaches her to make her life ``her own.'' The collection starts with Blew's nostalgic blurring of dream and memory but ends with Terry Tempest Williams's ``The Clan of One-Breasted Women'' about a Utah Mormon who discovers that the flash of light she thought was a dream was a real nuclear explosion and breaks with conservative tradition by questioning authority when her mother, both grandmothers and six aunts develop breast cancer. Although there are flawed contributions, this evocative collection with works by Tess Gallagher, Melanie Rae Thon, Anita Endrezze, Gretel Ehrlich, Cyra McFadden and others, coheres in examining Western myths and traditions through the lives of women. (July)\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThe editors have selected short stories, poems, essays, and excerpts from novels that present women's perceptions of the American Rocky Mountain West. These pieces, by writers as diverse as Tess Gallagher, Pam Houston, Gretel Ehrlich, and Deidre McNamer, are powerful, moving, and uniquely expressed. The common themes that thread through this collection include growing up, painful or strained family relationships, love for men and friends, and the West itself-mountains, forests, plains, rivers, horses, cowboys, and coyotes. The women describe the hardships that must be endured to survive the rugged terrain, harsh climate, and loneliness of the West. In their writing, past, present, memories, and dreams are reconciled. Recommended for most collections.-Cheryl L. Conway, Univ. of Arkansas Lib., Fayetteville\ \