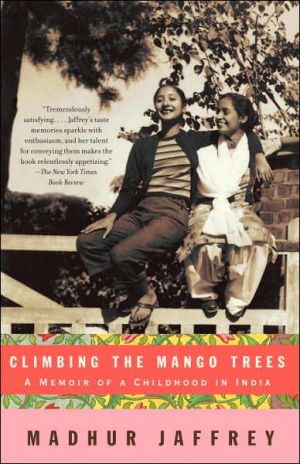

Climbing the Mango Trees: A Memoir of a Childhood in India

Today’s most highly regarded writer on Indian food gives us an enchanting memoir of her childhood in Delhi in an age and a society that has since disappeared.\ Madhur (meaning “sweet as honey”) Jaffrey grew up in a large family compound where her grandfather often presided over dinners at which forty or more members of his extended family would savor together the wonderfully flavorful dishes that were forever imprinted on Madhur’s palate.\ Climbing mango trees in the orchard, armed with...

Search in google:

Whether acclaimed food writer Madhur Jaffrey was climbing the mango trees in her grandparents' orchard in Delhi or picnicking in the Himalayan foothills on meatballs stuffed with raisins and mint, tucked into freshly baked spiced pooris, today these childhood pleasures evoke for her the tastes and textures of growing up. This memoir is both an enormously appealing account of an unusual childhood and a testament to the power of food to prompt memory, vividly bringing to life a lost time and place. Included here are recipes for more than thirty delicious dishes that are recovered from Jaffrey’s childhood. The New York Times - Jan and Michael Stern For those who now know her as a culinary authority, it s funny to learn that before leaving India she failed the cooking exam at school, where her formal kitchen education had concentrated on what she calls British invalid foods from circa 1930. She finally did learn how to cook via letters from her mother, but the irresistible savor of this memoir proves that taste precedes technique.

Climbing the Mango Trees\ A Memoir of a Childhood in India \ \ By Madhur Jaffrey \ Knopf\ Copyright © 2006 Madhur Jaffrey\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 140004295X \ \ \ ONE\ \ \ The orchard site had housed our family homestead only since the early decades of the twentieth century. My family actually came from the walled city, often called Old Delhi, just to the south, built by the Moghul Emperor Shah Jahan in the seventeenth century. My family referred to it simply as Shahar, or the City.\ \ There are many Delhis, as we were to study in school, all built either alongside each other or wholly or partly on top of each other, often reusing building materials knocked down in bloody efforts at domination. Our own original family home was in Chailpuri, in the narrow lanes of the Old City. It had as its carefully chosen foundation sturdy stones "borrowed" from the walls of Ferozshah Kotla, the fourteenth-century fortress and palace of a fourteenth- century emperor in a fourteenth-century Delhi.\ \ Starting with the ancient Vedic city of Indraprastha, which flourished in the fifteenth century B.C., a succession of Delhis was built, first by generations of Hindu rajas, only to be followed in A.D. 1193 by a roll call of Muslim dynasties: Ghori, Ghaznavi, Qutubshahi, Khilji, Tughlak, Lodhi, and Moghul. They seemed to trust the dubious comfort of walled cities,and their leaders chose to name Delhi, again and again, after themselves. This ended, at least from the point of view of my childhood, with the British version, sans walls, New Delhi, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and built in the ruin- filled wilderness south of the Old City walls.\ \ The Moghul capital, Shahjahanabad, or the Old City or the City, or Shahar, was where the written history of my family began. We were only blessed with our paternal side of it. My mother's side either kept few records or humbly kept its accomplishments under wraps. This written history, bound in red, was kept in my grandfather's home office.\ \ When my grandfather--Babaji, as we called him--decided to move out of the City to the orchard estate, he was already a very successful barrister. His new house, the one in which I was born, was a brick- and-plaster version of a multi-roomed, grand Moghul tent with bits of British fortress and Greco-Roman classicism thrown in to hint vaguely at grandeur. The road it was built on was named after my grandfather, Raj Narain Road (with the patriotic Hindification of names that followed Independence, it is now Raj Narain Marg), and had the number 7 on its front gate. From the time I can remember, we always referred to that house as Number 7, as in "I'm going to Number 7," or "You know that big tamarind tree in Number 7. . . ."\ \ Not wishing to waste money, and full of the brio of someone recently "England-returned" (he had been studying law in London), he designed it all himself. As the family story goes, it was at this time that the British had decided to move their capital from Calcutta to Delhi, and Lutyens was in the process of building the new capital, to be named New Delhi. Lutyens asked my grandfather to pick any piece of land in New Delhi and build on it--Lutyens might have designed the house himself had my grandfather asked--but my grandfather dismissed the whole idea, saying, "Who wants to live in that jungle?" Properties in "that jungle" are now worth as much as those in central London and midtown Manhattan.\ \ Years later, having proceeded beyond my three score and ten years, I was awarded an honorary CBE (Commander of the British Empire) by Queen Elizabeth II in Washington, D.C., another city designed by Lutyens, in a house also designed by Lutyens, the British ambassador's residence. As I stared at my reflection there in a pair of dark Lutyens mirrors, dotted with glass rosettes, I couldn't help thinking that my life might have come full-circle. I could have been born in a Lutyens house and received a grand recognition of my life in a Lutyens house. But I was not destined for such easy symmetry, for easy anything.\ \ Babaji's whitewashed house consisted of a central "gallery"--a hall, really--leading to five very large rooms with fireplaces. One of these was the drawing room, and the others served as bedrooms, one to a family. Running along the front and back of the house were two long verandas lined with semi-classical, semi-Greco-Roman pillars. The back, east-facing veranda looked out on the Yamuna River, or, as we called it with great familiarity, the Jumna River. It was here that so many of us, as infants, were rubbed with oil and left to absorb the morning sun. Because the land must have sloped down to the water, this veranda was one floor up, built over a very large, partially underground, damp, always cool cellar or taikhana. My grandfather used to make wine here from grapes he imported from Afghanistan, but that must have been before I was born.\ \ The front, west veranda faced the gardens, which had incorporated the remnants of the old orchard and now included a winding drive to the front gate. The front and back verandas ended in rooms at each corner of the house, the front ones being shaped somewhat like turrets. The functions of these corner rooms changed over the years, but one of them at the back, facing east and south, always remained my grandmother's--and the family's--chapel-like, Pooja ka Kamra or Prayer Room. On top of the house were two levels of flat roofs, the one in the center being higher, and both edged with a battlement-like balustrade.\ \ But the main house was not large enough to fit the only army Babji was to see, a growing army of spirited grandchildren produced by his eight children. Some of these progeny lived at Number 7 all the time, and some came and went. Babaji firmly believed in the joint-family system, with himself presiding as the head of his brood, a system that had been followed by his father and grandfather and, indeed, by all his ancestors.\ \ So, in addition to the main house and gardens, across two vast brick courtyards to the north and south of the main house, were two long, trainlike, one-room-wide annexes. Made of unpainted brick, they had a more casual, country feel. The one to the north started at the river end with the dining room and then went on to pantries, storage rooms, and the kitchen. Beyond it, across another bit of courtyard on the same north side, was the Boiler, industrial in size and used for making extra hot water for our winter baths, and an annex of bathrooms. The annex to the south, known simply as the Rooms (Kamras), also started at the river end. It contained my middle uncle's bedroom and offices, then my grandfather's offices, and then extra rooms for guests. Besides all this there was a shed for cows and horses, a servants' annex, and two sets of large garages.\ \ It was in my grandfather's southern-annex office that I one day discovered, by complete chance, a book bound in red that was the family's history. (I must have been thirteen at the time.)\ \ There were actually two types of family history. There was the documented version that sat properly in my grandfather's office. But there was also the undocumented version, consisting of fables, family customs, and hearsay passed along by my grandmother Bari Bauwa and the other women of the house. This version had begun seeping into us since birth, very subtly, with the honey on our tongues. And, to start with, it was the only one I knew.\ \ Every autumn, at the religious festival of Dussehra, Bari Bauwa would demand that we bring all our writing implements to the Prayer Room. The men would be asked to bring their guns as well. She would arrange these in the altarlike temple she had set up--Parker pens, bottles of blue-black Quink, pencils, hunting rifles--all mixed in with gods, sacred threads, and marigolds. The women and children would gather inside the Prayer Room, with the men always hovering, unconvinced, by the doors. We would begin praying and sprinkling these rather ordinary implements with yellow turmeric powder, red roli powder, grains of rice, holy water, and flower petals. I thought then that all of India was doing what we were doing: asking blessings for pens and pencils and guns.\ \ What I did not realize was that on that day most Hindus were asking God to bless the implements they worked with: farmers wanted blessings for their bulls and plows, and traders for their weights, measures, and coins.\ \ But who were we, and why was my bottle of Quink in the Prayer Room? According to the women's oral history--and this was never taught to us, just deduced slowly over time--we were a subcaste of Hindus known as Kayasthas: Mathur Kayasthas, to get the sub-subcaste right. Even as a child, I saw it so clearly in my imagination. . . . Roll the film: Ancient India. Day. A vast meeting of notables is being held on a mountainside to finalize the caste system. At the top of the heap, it is announced, are to be the self-satisfied priests, the Brahmins, who will be the only ones allowed the privilege of reading, writing, and making laws. There is much cheering from their quarter. Below them are to be the warriors, Kshatriyas, who will fight and rule kingdoms. This lot seems overjoyed, too. Lower on the totem pole will be the traders and farmers, Vaishyas, whose eyes glint at the thought of making money, and even further down, the menial workers or Shudras, who stand glum and silent.\ \ The camera shifts. Next day. Night. A small hall lit with oil lamps. A smaller meeting of agitated intellectuals. They are overwrought because they are viscerally against all these categories. In any case, they do not fit neatly into any of them. Reading, writing, and making laws is what gives them the most satisfaction, but religious orthodoxy scares them, and they want none of it. They have no fear at all of ruling any part of the world, but they will not give up their precious books. They lack both the sort of entrepreneurial spirit that makes successful traders (in fact, hush, they look down on traders), and the physical strength and desperation that sustain farmers. So they vote rather boldly to form a union of their own, a separate subcaste of freethinking writer-warriors to be known as Kayasthas. The End.\ \ That is my version of events. There is actually a real legend, if legends can be real, that goes something like this: Just after Brahma, the God of the Universe, had created the caste system with, in descending order, the Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras, a worried Yama, God and Chief Justice of the Underworld, approached him, saying, "I need an assistant who has the ability to record the deeds of man, both good and evil, and to administer justice." Brahma went into a trance. When he opened his eyes, he saw before him a glorious figure of a man holding a pen in one hand, an inkpot in another, and a sword tied around his waist. Brahma spoke: "Thou hast been created from my body [kaya], therefore thy progeny shall be known as Kayasthas. Thy work will be to dispense justice and punish those that violate Divine laws." Brahma gave him the special caste of Dwij-Kshatriya, twice-born warrior.\ \ \ \ Another such "history" lesson came directly from my grandmother. I will never forget the day.\ \ It was one of those sunny but crisp, cold winter Sundays that Delhi loves. Winter lasted only two months a year, and our family turned quite British for this season. At least in our clothing. All the tweed coats and jackets (British fabrics, Indian tailors) and cardigans (British wool and patterns, family-women knitters) came out of mothballed trunks. They were spread out on the lawn and sunned repeatedly for days, in a desperate effort to rid them of their naphthalene odor, after which they were hung or folded up and put into cupboards. The women wore hand-knitted cardigans on top of their sarees and then bundled themselves further in Kashmiri shawls.\ \ I was ten and looking smart as smart can be in my pale-blue herringbone-patterned woolen overcoat, made to measure at Lokenath's in Connaught Place, New Delhi. (My two older sisters had exactly the same coats.) It was January, and so cold that we had to wear overcoats both inside and outside the house. I smelled of mothballs.\ \ About twenty of us had barely collected in the dining-room annex for breakfast when the Lady in White arrived. Of the same age as my grandmother, she was habitually enshrouded in a long white skirt or lahanga, a white bodice, and a white covering over her head. Her skin color matched her clothing. I used to think that my mother was the whitest Indian I knew until I met the Lady in White. My mother was the color of cream. The Lady in White was the color of milk. What mattered most to us, though, was not her milky color but the milky ambrosia that she carried on her head.\ \ Yes, balanced there, on a round brass tray, were dozens of mutkainas, terra-cotta cups, filled with daulat ki chaat, which could be translated as "a snack of wealth." Some cynic who assumed that all wealth was ephemeral must have named it. It was, indeed, the most ephemeral of fairy dishes, a frothy evanescence that disappeared as soon it touched the tongue, a winter specialty requiring dew as an ingredient. Whenever I asked the Lady in White how it was made, she would sigh a mysterious sigh and say, "Oh, child, I am one of the few women left in the whole city of Delhi who can make this. I am so old, and it is such hard work. What shall I tell you? I only go to all this trouble because I have served your grandmother from the time she lived in the Old City. First I take rich milk and add dried seafoam to it. Then I pour the mixture into nicely washed terra-cotta cups that I get directly from the potter. I have to climb up the stairs to the roof and leave the cups in the chill night air. Now, the most important element is the dew. If there is no dew, the froth will not form. If there is too much dew, that is also bad. The dew you have to leave to the gods. In the early morning, if the froth is good, I sprinkle the cups with a little sugar, a little khurchan [milk boiled down into thin, sweet, flaky sheets], and fine shavings of pistachios. That, I suppose, is it."\ \ Those cups were the first things placed before us at breakfast that day. Our spoons, provided by the Lady in White, were the traditional flat pieces of bamboo. Heavenly froth, tasting a bit of the bamboo, a bit of the terra-cotta, a bit sweet and a bit nutty--surely this was the food of angels. \ \ Continues... \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Climbing the Mango Trees by Madhur Jaffrey Copyright © 2006 by Madhur Jaffrey. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ From Barnes & NobleReading Madhur Jaffrey's aromatic memoir, one almost feels that the tone of her whole life was set on her very first day. When she was born, her grandmother carefully spelled out the minute word "Om" in honey on her tongue, and she was given the name "Madhur," literally "sweet as honey." This future food writer and actress writes about her life in pre-Partition Delhi with fondness, filling page after page with vivid memories of childhood outings and sweet yogurt treats; in her hands, even monsoon season and chickenpox become occasions for visceral memories and shared love. Climbing the Mango Trees cascades forward, moving smoothly from vignette to vignette, allowing us to freely sample the tastes and texture of an India now gone.\ \ \ \ \ Jan and Michael SternFor those who now know her as a culinary authority, it’s funny to learn that before leaving India she failed the cooking exam at school, where her formal kitchen education had concentrated on what she calls “British invalid foods from circa 1930.” She finally did learn how to cook via letters from her mother, but the irresistible savor of this memoir proves that taste precedes technique.\ — The New York Times\ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThe celebrated actress and author of several books on Indian cooking turns her attention to her own childhood in Delhi and Kampur. Born in 1933 as one of six children of a prosperous businessman, Jaffrey grew up as part of a huge "joint family" of aunts, uncles and cousins-often 40 at dinner-under the benign but strict thumb of Babaji, her grandfather and imperious family patriarch. It was a privileged and cosmopolitan family, influenced by Hindu, Muslim and British traditions, and though these were not easy years in India, a British ally in WWII and soon to go though the agony of partition (the separation and formation of Muslim Pakistan), Jaffrey's graceful prose and sure powers of description paint a vivid landscape of an almost enchanted childhood. Her family and friends, the bittersweet sorrows of puberty, the sensual sounds and smells of the monsoon rain, all are remembered with love and care, but nowhere is her writing more evocative than when she details the food of her childhood, which she does often and at length. Upon finishing this splendid memoir, the reader will delight in the 30 "family-style" recipes included as lagniappe at the end. Photos. (Oct. 11) Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ KLIATTJaffrey was born in India in the 1930s, and thus is the age of grandparents of today's adolescents. She has been praised for her books about Indian cooking, winning coveted awards. Her face is familiar because of her career as an actor in films. Climbing the Mango Trees tells of exotic family life in India, with the food prepared and eaten a central fact of that life. It's unusual that a memoir focuses so intently on food--the tastes of a family. At the end of the narrative are 50 pages of family recipes. Any young person who has grown up in an Indian family would have an immediate connection with Jaffrey's memoir because of the food, and perhaps it would help intergenerational understanding. Jaffrey grew up in a large, middle-class family, for many years sharing a home in Delhi with grandparents and uncles and aunts and cousins. In fact, the cousins did climb up onto the branches of the mango trees in the yard to eat the fruit, green or ripe. This was the time of colonial rule by the British, of course, and Madhur and her sisters attended private English-language schools, starting school not understanding a word of English. Especially of interest to Indian American readers, and to all who love Indian cuisine. Age Range: Ages 15 to adult. REVIEWER: Claire Rosser (Vol. 42, No. 1)\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalReaders will be surprised to learn in this culinary memoir that Jaffrey (An Invitation to Indian Cooking), one of the best-known writers on Indian cuisine, actually failed home economics. Although she later learned to prepare the traditional Indian food of her childhood, her early culinary education was primarily concerned with outdated recipes from British colonial days. What is not surprising is that Jaffrey, a descendant of a long line of record-keeping Kayastha Hindus, is a gifted and generous writer. She shares treasured recollections of how her close-knit family lived in Delhi, conveying the safety and warmth of the presence of many siblings and cousins, the love of food and learning, and the unease and disturbance of the partition of India and Pakistan. Thirty-seven photographs of the author and her family are scattered throughout. There are more than 30 family recipes, including Phulkas (a kind of Indian flatbread), Mung Bean Fritters, and Ground Lamb Samosas, all written in Jaffrey's easy style. Highly recommended for all public libraries. [See Prepub Alert, LJ 6/1/06.]-Rosemarie Lewis, Broward Cty. P.L., Ft. Lauderdale, FL Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsA beloved food writer recalls her youth through the lens of cuisine. Jaffrey (Market Days, 1995, etc.) grew up in India during the 1930s and '40s, the fifth child of two doting, well-heeled parents. Her family was Hindu, but embraced certain touches of Muslim culture: The women wore both the loose culottes favored by Muslims and long, traditional Hindu skirts; at school, Jaffrey studied alongside both Muslim and Hindu children. Her story has no clear narrative arc and no tension that requires resolution, but the meandering is pleasant. Almost every vignette includes a description of food. When she was born, her grandmother spelled out the word Om in honey on her tongue, and Jaffrey's first name translates to "Sweet as Honey." Summer afternoon thirsts were slaked with fresh lemonade or a mixture of fruit syrup and water. Monsoon season brought its own sweet treats of chilled mango juice and "pretzel-shaped jabelis" dipped in milk. A long bout of chicken pox was made bearable by her grandmother's chutney. Even Partition had culinary consequences: Hindus who headed into India from what became West Pakistan introduced Delhi to Punjabi food, including the terrific paneer dishes and tasty tandoori specialties that are now staples of Indian restaurants. Punjabis also loved dairy products; they made the richest yogurt, and the creamiest lassi, a cool yogurt beverage. As an adult, Jaffrey went to college and then moved to England to study drama. Not until she landed in London did she really begin to appreciate her mother's cooking. She wrote home, begging for instruction on preparing the delicacies of her youth, and soon airmail letters thick with recipes began to arrive. Fifty pages of thoserecipes round out the text. Readers will lap up this mouthwatering memoir and hungrily await a sequel. First printing of 40,000\ \