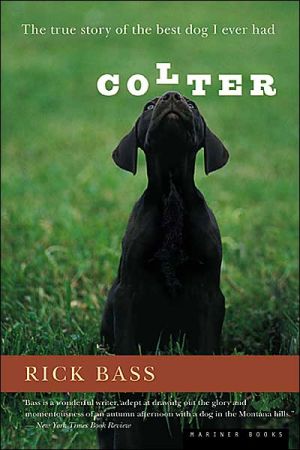

Colter: The True Story of the Best Dog I Ever Had

COLTER pairs one of America's most treasured writers with our most treasured "best friend." Colter, a German shorthair pup, was the runt of the litter, and Rick Bass took him only because nobody else would. Soon, though, Colter surprised his new owner, first with his raging genius, then with his innocent ability to lead Bass to new territory altogether, a place where he felt instantly more alive and more connected to the world. Distinguished by "crystalline, see-through-to-the-bottom prose"...

Search in google:

COLTER pairs one of America's most treasured writers with our most treasured "best friend." Colter, a German shorthair pup, was the runt of the litter, and Rick Bass took him only because nobody else would. Soon, though, Colter surprised his new owner, first with his raging genius, then with his innocent ability to lead Bass to new territory altogether, a place where he felt instantly more alive and more connected to the world. Distinguished by "crystalline, see-through-to-the-bottom prose" (Rocky Mountain News), this interspecies love story vividly captures the essence of canine companionship, and yet, as we've come to expect from Rick Bass, it does far more. "With an elegant, often erudite flavor to this story" (Book Page), COLTER illuminates the heart of life by recreating the sheer, unmitigated pleasure of an afternoon in the Montana hills with a loyal pup bounding at your side. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel [A] gorgeous, heart-tugging man-and-dog memoir.

\ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ After that first miracle season-miraculous if only for one grouse at dusk, in which flame leapt from the end of the gun-I had a hard decision to make. I didn't know much about birds, or bird-hunting, but I knew that I had a raging genius on my hands. And I'd bragged on him to my friend Jarrett Thompson, the best trainer in the world, who was anxious to see Colter and to work with him.\ Jarrett's Old South Pointer Farm was in Texas, though, and it seemed inconceivable to me to separate from Colter. To not be the one to feed him twice a day-to not have him bounding ahead of me on walks. To not see him for weeks at a time-as if he had cast too far out in front of me, working some thin ribbon of scent. As if he were up ahead, hunting without me. I went back and forth in my mind, tortured. It took about a month before I finally decided to do what was best for Colter, rather than for me. I flew to Houston with him in the spring, and then my father and I drove him up to Jarrett's place.\ Jarrett complimented Colter on his good looks: he was the only brown dog on the farm, amidst perhaps a hundred other white dogs-white and lemon pointers, white and liver ones. Colter's muscles stood out deeper than those of the other dogs. I said my good-byes to him and left, and I carried with me that huge and strangely empty feeling of having made a life-changing, or life-turning, decision, but having no clue whatsoever whether it was the right one.\ Some people say pointers are crazy, others say it is their owners. Jarrett's too diplomatic to take sides, but he has some stories. One of his favorite's is about this big hunterfrom Florida-big in the sense that he weighed three hundred pounds. The guy came to Jarrett's farm to drop his dog off, and at the moment of parting, he hugged his dog-a monster itself, an English pointer weighing almost eighty pounds-and then he took Jarrett aside and handed him a gallon of Jack Daniels.\ "Now Thompson," he says, "Old Buck and I each have a glass of whiskey in the evenings after we get through hunting, and I expect y'all to do the same."\ Then there was the oil man from west Texas, Odessa, who decided he wanted a bird dog-one of the best-but he wanted a friendly dog, one he could keep in the house. So he flew to Rosanky in his Lear jet and picked out one of the dogs Jarrett had raised and trained to sell. It cost him about three thousand dollars to bring the jet over there, and another twenty-five hundred for the dog, Ned. Jarrett drove him back to the airport in Austin, where the jet was waiting, oil derricks painted on its tail. The oil man put Ned right up there in the front seat and strapped him in with the shoulder harness next to the pilot, Ned looking all around and wondering, perhaps, if he would ever hunt again. The pilot, says Thompson, was rolling his eyes-dog hair on the seat and Ned panting, Ned slobbering.\ A week later Thompson got a call from the oil man. "I think Ned's homesick," he said. "Can I fly him home and give him back to you? I'll pay you a thousand dollars to take him. All he does is lie around by the refrigerator," the man said. "I think he misses you, and misses the other dogs. I feel bad about it."\ Another pointer-owner came driving down the road one day, bringing his dog along, wanting to see what Jarrett's farm was like. He was thinking about leaving his dog, Sarge, in Jarrett's care. "\ \ \ I had him take me out in the woods," Jarrett says, "just to see what kind of dog Sarge was-what he could do, and what I could expect from him. To see if he had any spark.\ "Before we started to do anything, though, the guy-I can't remember his name either-asks if he can have a minute with Sarge, and I say sure, not knowing what's up, and he takes Sarge off a little ways and tells him to sit, and then he starts talking to him, the way you and I would talk. I'm trying not to listen, and it's making me feel funny, but what this guy's saying, real quietly, is stuff like, 'O.K., Sarge, we drove a long way out here, now I sure hope you're not going to embarrass me'-just talking to him real gently and kind and quiet-and I'm trying not to listen, but I'm also getting kind of interested, kind of eager to see what kind of dog this Sarge is, that you can talk to like a person, instead of a dog. "Well, we get out and walk a ways, and Sarge kind of cuts up, blows a point, and misses another, and the man was just getting all pained, writhing and flinching. Every time Sarge messed up, he'd take him aside and have another talk with him-I could hear him saying, 'Sarge! You're embarrassing me!'-and finally, when it just wasn't getting any better, the man, all sweating and upset, asked if he could have some more words with Sarge, alone.\ "They got in their truck and drove down the road a ways-I thought they were leaving-and then they stopped under a shady tree-I could see them sitting there, talking-and after a while the guy drives back, still looking all pained, and he says to me, 'Sarge and I had a little talk down at the gate and we decided it's best for Sarge to stay here for a while.'"\ All summer, I still didn't know if I'd done the right thing. The house seemed empty, the yard seemed haunted, without Colter. The older hounds, Homer and Ann, were thrilled, I think, that the newcomer, the upstart and thief of affection, had been sent away, that things had turned back to the way they used to be. Oh, the wretched excess of the heart! Once a month, through the summer, I would fly to Texas and meet my father in Houston. We'd drive toward Austin, to Jarrett's farm, and turn down his long red clay driveway just at dawn. There is a little bluff, a fault line, slanting through Rosanky like a thin ribbon of scent, which allows pine forests to flourish in an otherwise scrub-brushy country, and we would drive past the big pines, and past all the dogs leaping in their kennels and barking, and Jarrett would greet us with a cup of coffee. He began all his days early in the spring and summer. It was important to work the dogs before the sun got too high and the heat burned the dew off the grass and made it hard for the dogs to smell the birds.\ Each time, Jarrett would show me Colter's prog- ress. And each time, I would be amazed at the finesse, the precision of execution required from a point- ing dog. It has to learn so many things, and execute, every step of the way. Finding and pointing the bird is easy-it comes naturally. Working within range can be taught, eventually. But teaching the dog not to run after the bird when the bird flushes-not so easy. How to teach an animal to want something, but then, when the thing flies, to not want it? And to teach it not to run after a bird if it bumps one by accident-and to not run after the bird when you shoot? Steady-to-wing, they call it; steady-to- shot. And finally, the greatest challenge, steady-to-wing-and-shot. If he had been less of a dog I would have tried to train him myself, making mistakes the way I do when I take something apart and then try to put it back together. But at least I had the sense to know this was a living, breathing talent-not some car engine, or a watch-who was going to be with me for the next ten years or more, both of us hunting fifty, sixty days a year-and that he deserved better. The realization that I had, against my usual odds and inclination, somehow done the right thing came not at once, but in small increments, like confidence. Throughout the course of the summer I'd been fantasizing about taking Colter out of school a little early, to start the September grouse season in Montana, but Jarrett said that he needed more work, that he was still in a learning transition-he was starting to make real progress, but it was a very critical time for him.\ I would panic, thinking, I just want my dog back. I would panic, and wonder, What good is it to have a great dog if you can't hunt with him? Nancy, I could tell, was also unhappy about Colter's long absence from the valley, though she didn't say anything about it to me. She did ask Elizabeth once, "Doesn't he love Colter anymore?" And Elizabeth just laughed . . .\ He was getting so big and muscular-each time I went to visit him he looked more like some hardened old muscular male bird dog, with only one thing on his mind. Where was my adolescent goofy-gangling little pup? He would leap up and run to greet me as ever, but more briefly each time, before sliding past and prancing around Jarrett's four- wheeler, on fire to go out into the field and hunt, even if only for a half-hour or so, as he did every day. Every day.\ "I really like this dog," Jarrett would say. "I see a lot of dogs, but I really like old Colter. I think you could make a great field trial champion out of him," he'd say, meaning that Jarrett could do it, if I'd let him keep Colter all year long. "Oh, I'm real anxious to get him home and start hunting with him," I'd tell him every time, and Jarrett would nod and look down at the brown dog he was spending every day with, and starting to respect and love, and he wouldn't say anything, and I'd wonder at what a hard job it must be for him: at how it was hard, in a different way, for him, and hard for me-hard for everyone but Colter.\ "Do you ever dream about bird hunting?" I asked Jarrett.\ "All the time," he said.\ "Me too," I said, comforted that Jarrett, after a lifetime, still dreamed of it-that I have that to look forward to; that this was not love's first flush, but the real thing.\ "Do you think the dogs do?" I asked.\ "I'm certain of it," said Jarrett.\ A bittersweet, lonely, early autumn of hunting grouse in my valley, the Yaak, with Tim and Maddie, but no Colter. Barely able to wait another day. Leaves turning color-no Colter!-and then, even worse, falling from the branches, and still no Colter there to see it with me, to taste it and smell it, to hunt it, each day. Deer and elk season begins: a blessed relief. I disappear into the snow and fog.\ And then one day Jarrett says Colter is ready- that he can take a little break, that it's the end of his session-but that he wants to see him back next year. I go south one more time to pick up my dog. On the plane, my secret feels delicious: I am the richest man in the world, I have the greatest, most exciting dog in the world, and all around me, people are fooling with their coffee and ordering little cups of yogurt and reading their damn newspapers, while I have a bursting secret, and with pheasant season still open in Montana. Everyone else is stumbling around in the airport as if they don't seem to know that the world, and my heart, and the dog's heart, are on fire.

\ From Barnes & NobleFor many of us, it doesn't require much writing skill to make a dog story endearing. But even the most avid pet fancier will recognize the Rick Bass's tribute to his hunter Colter is the best in the litter.\ \ \ \ \ Vicki CrokeAgain and again, Bass is experiencing that great lesson dogs have to teach: to accept the ones we love for who they are, to embrace even the faults…There is something interior, something luminous, a spirit yet invisible to the world in the bond between people and dogs.\ — Washington Post\ \ \ Milwaukee Journal Sentinel[A] gorgeous, heart-tugging man-and-dog memoir.\ \ \ \ \ Elizabeth Marshall ThomasSplendid...a tribute to great dogs everywhere.\ \ \ \ \ Boston GlobeThe most impressive work from Bass in years...as clean and clear as the human and natural landscape it explores.\ \ \ \ \ Detroit Free PressBreathtaking...If any writer can awaken a taste for outdoors, Bass can.\ \ \ \ \ Publishers Weekly"How we fall into grace. You can't work or earn your way into it. You just fall. It lies below, it lies beyond. It comes to you, unbidden," writes novelist and essayist Bass (Where the Sea Used to Be, etc.) of the arrival of his "goofy little knot-headed" genius of a pointing dog. As they roam the remote western Montana valley where Bass lives, and hunt the golden autumn plains in the eastern part of the state, Colter unfailingly ushers Bass into "an unexplored land" where the two become "as alive as we have ever been: our senses so sharp and whittled alive that we could barely stand it." Their prolonged hours of "wanting only one thing, a bird, wanting it so effortlessly and purely that [we] come the closest [we] will ever come to a shared language" are a blessing. But always, for Bass, there is the undertow of paradox: of living for the hunt but being a comically rotten marksman; of being a hunter yet an environmentalist; of his tendency to love with "a passion so intense it borders on gluttony," inevitably followed by the crushing numbness that marks the loss of what he loves. Bass's exhaustless appetite for natural beauty and his propensity for "bragging on" his dog occasionally lead to exuberant repetition ("It was just so damn great to be out in such open country with my dogs"), but more often result in luminously transcendent passages on the education and sorrowful loss of a brilliant and mischievous chocolate brown pointer that will transfix anyone who has ever loved a dog. (June) Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\|\ \ \ \ \ From The Critics"Colter is a dog of boundless spirit, all grace and wild genius. And his terrific master, Rick Bass, happens to be a national treasure. What a terrific team they make!" -- Carl Hiaasen, author of SICK PUPPY\ \ \ \ \ KLIATTHere is a very readable book in the line of The Voice of Bugle Ann and Old Yeller. Rick Bass owned dogs before Colter, and he will own dogs again, but there will never be another dog as dear to him as this brilliant (although slightly goofy) shorthaired pointer. Bass writes in a breezy tone, as if he's talking to the reader, and his enthusiasm is infectious. Even an anti-gun, anti-hunting "peacenik" who can't even picture the vastness of a Texas meadow or the vista of the Rocky Mountains in Montana and who knows virtually nothing about the birds that Colter can scent from miles away can find herself caught up in tales of Colter's abilities. Bass is realistic about Colter's goofiness and doesn't hesitate to laugh at him. The laughter is often at Bass himself, though—for a man who hunts with his dog as much as he does, he's a remarkably bad shot! But he doesn't care. The point is to be outside with his dog. Of course dogs don't live as long as humans, and the story of Colter's death is particularly wrenching. Bass is training one of Colter's brothers (who will never be the hunter Colter was) as he is grieving, and though some might underestimate Bass' depth of feeling, and his degree of mourning, for "just a dog," the reader will understand perfectly. The only objections I have to the book are in Bass' use of profanity (although words like "dipshit" and "fucked-up" are almost standard in much modern writing) and the occasional typo (indenting some but not all in a set of paragraphs that should have matched) but these are minor complaints.A good read. KLIATT Codes: SA—Recommended for senior high school students, advanced students, and adults. 2000, Houghton Mifflin, Mariner,188p., $10.00. Ages 16 to adult. Reviewer: Judith H. Silverman; Chevy Chase, MD , November 2001 (Vol. 35, No. 6)\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThis delightful book is really a love story about the special bond and level of understanding that can exist between a man and his dog. It is also a story that celebrates nature, describing life in the Montana woods and the thrill of hunting in the never-ending fields at the foot of the Rocky Mountains. In his latest book, nature writer Bass (The Sky, the Stars, the Wilderness) tells the story of life with a very special hunting dog. Colter is the runt of the litter, and Bass ends up buying the pup because no one else wants him. But as he grows, Colter's instinct takes over, and his passion for hunting is unequalled. The dog's abilities are so outstanding that Bass, admittedly a poor shot, feels guilty when he misses a bird because he feels that he is letting his dog down. His enthusiasm is contagious and somewhat amusing: Bass loves to hunt, but does not particularly care whether he shoots anything; it is the thrill of watching his dog work that he finds exciting. Recommended for public libraries. [Previewed in Prepub Alert, LJ 2/15/00; BOMC selection.]--Deborah Emerson, Monroe Community Coll., Rochester, NY Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\\\ \ \ \ \ Richard ConniffBass is a wonderful writer, adept at drawing out the glory and momentousness of an autumn afternoon with a dog in the Montana hills. \ —New York Times Book Review\ \