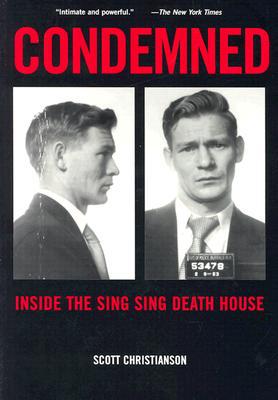

Condemned: Inside the Sing Sing Death House

From 1891 to 1963, New York's infamous Sing Sing was the site of 614 legal executions carried out by the state. More people were executed there than at any other American prison, yet Sing Sing's death house was, to a remarkable extent, one of the most closed, secret, and mythologized places in modern America.\ In this remarkable book, based on recently revealed archival materials, Scott Christianson takes us on a disturbing and poignant tour of Sing Sing's legendary death house, and...

Search in google:

From 1891 to 1963, New York's infamous Sing Sing was the site of 614 legal executions carried out by the state. Christianson, a former investigative reporter and state criminal justice official, gives details on the legendary death house and introduces those whose lives were claimed in its electric chair through mug shots, letters, and telegrams. While the majority of inmates were everyday people, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were also executed here, as were major figures in the infamous Murder, Inc., forerunner of the American Mafia. Lacks a subject index. The author is director of the New York Death Penalty Documentation Project. Annotation c. Book News, Inc., Portland, OR Library Journal For the first time since archival records were opened in 1977, readers can take a tour of Sing Sing Prison's infamous death house. From 1891 to 1963, 606 men and eight women were legally executed there in the electric chair. These executions were carried out with the strictest security away from public view. Yet journalist accounts of some of the high-profile capital cases made Sing Sing famous the world over. Investigative reporter Christianson (With Liberty for Some) has compiled the mug shots and dossiers of 70 condemned inmates with pictures of their physical surroundings. The result is a slim volume of indelible impressions. Today, Sing Sing is an average New York State correctional facility. Executions are no longer carried out there, and its notoriety has been eclipsed by more dreaded prisons in other states. Sing Sing's legacy, however, will likely remain an important part of America's history of criminal justice. Highly recommended.--Frances O. Sandiford, Green Haven Correctional Facility Lib., Stormville, NY Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\\

\ \ \ \ \ Introduction\ \ \ From 1891 to 1963, 606 men and eight women were legally executed in the electric chair at New York's infamous Sing Sing Prison — more than at any other American prison. The capital punishment systems and procedures that were developed at Sing Sing established the prototype for modern legal prison-based executions, and the resulting media coverage helped shape public perceptions of crime and punishment, good and evil, and gangsters versus guardians of public safety. For millions of persons around the world, the Sing Sing Death House was capital punishment.\ Some of Sing Sing's higher-profile cases received sensational coverage by reporters from newspapers, pulp magazines, radio, and newsreels, spawning more than a dozen major Hollywood movies that imprinted chilling images of the chair, the last mile, and other macabre conventions onto the minds of generations of Americans. The place was so famous that a letter mailed from abroad and addressed simply to "Sing Sing, U.S.A." was likely to find its way into the warden's hands. Already a household word a half century before the electric chair came on the scene, Sing Sing became the most famous prison in the world.\ And yet, despite all the attention it received over the decades, Sing Sing's death house was one of the most closed, secret, and mythologized places in America—a closely guarded and rigidly ruled inner sanctum that operated beyond the bounds of public scrutiny or humankind, and a killing machine that ran seemingly on its own power and volition and according to its own irrevocable rules. Every facetoflife inside was controlled and prescribed by the prison authorities. Outsiders were strictly forbidden to enter without a court order; even an FBI agent or top law-enforcement officer required official approval to get inside, and those wishing to witness an execution were thoroughly screened and allowed to attend only if they carried an official invitation.\ Information was tightly controlled. Reports about the prison behavior and character of condemned convicts were left to journalists and scriptwriters to construct as they saw fit, with all the limits and imperatives of a morality play. Long after the executions stopped, evidence of what had really happened inside the forbidding walls remained buried in bulging internal files or had vanished into eternity.\ On April 8, 1977, however, as part of an excavation of prison history and after months of official wrangling, a staff archivist from the State Department of Education was authorized to take custody of some dusty old official records stored at the Ossining Correctional Facility (Sing Sing) in Westchester County, about seventy miles north of New York City. Some of the boxes contained records relating to the death house. This removal of the cardboard boxes in 1977 marked the first time that behind-the-scenes documentation of the executions at Sing Sing had ever been allowed outside the prison walls. By then, the death penalty itself seemed a relic of the past; the last execution at the facility had taken place in 1963, and restoration of capital punishment in New York seemed unlikely. At most, the records seemed a fitting subject for eventual study by historians, but they did not appear to have much current legal or political value.\ For several years the prison records remained in official custody, closed to all but a few viewers. Finally, after years of cleaning, review, cataloging, and accessioning, a collection of some of the records was made available to authorized researchers at the New York State Archives in Albany. The materials from the death house included copies of two receiving blotters for the period 1891-1946, a log of legal actions involving condemned prisoners covering the period 1915-1967, assorted other prison logs, and a selection of 153 inmate case files spanning the period 1939-1963. The Department of Correctional Services still has not turned over to the archives the records for the bulk of the inmates who passed through the death house during its more than 79-year history, and fragments of some of the files occasionally turn up in the hands of private collectors or are discovered in library holdings.\ Despite its limitations and gaps, the archival collection offers a revealing look into the internal administration of capital punishment as it actually existed, not just as it was constructed by image makers or recounted by self-serving survivors. The case records cover part of the Great Depression, World War II, some of the Cold War and the prosperous 1960s, and the early civil rights era. Some files hold personal effects such as rosary beads and religious medallions, Social Security cards, frayed snapshots, and intimate correspondence. Each contains a standard dossier that includes the convict's personal and criminal history, medical information, psychological assessments, relevant court activity, previous prison record, secret surveillance reports, appeals papers, clemency requests, visiting records, intercepted correspondence, executioner's card, death certificate, autopsy report, and other data, making up an official compendium or master file that was intended to be accessible to only a few trusted prison officials. At the time the dossiers were compiled, nobody dreamed they would someday be made public. Now that they have been placed in the archives, some state officials do all they can to restrict access to them.\ Wedged within the files are individual black-and-white photographs (mug shots), taken by a prison identification specialist, of each newly arrived prisoner. Each profile view includes the inmate's prison identification number, indicating the order in which he or she was received at Sing Sing, and the admission date. The frontal view captures the subject's facial appearance and emotional expression. Most new inmates in the photographs still wear the formal, out-to-court clothes they had on earlier that day, when they learned the verdict, received a death sentence, and found themselves transported under guard into the death house. As might be expected, some of the faces photographed show the full effect of these recent experiences. Many also bear assorted visible scars and disfigurements, accumulated over their brief but hard lives. Nearly all carry somber, sullen, or resigned expressions before an indifferent lens. Some seem defiant, some bewildered, but most appear struck by an awful realization. Although presented as numbers, the condemned in these pictures come alive as human beings.\ For this book, excerpts from these previously secret state files and other records have been provided to form a sequence of images depicting life and death in the Sing Sing Death House, mostly during the 1940s and 1950s. But in many respects the images are timeless. Together with documentation that presents some of the state's internal evidence about the nature and administration of the death penalty, these records provide a rare and authentic glimpse of both the humanity of the condemned and the banality of the rules and methods of the executioners. The selections also offer occasional insights about the involvement of outsiders: witnesses, victims, and next of kin. The disclosures from officialdom are at once secretive and public.\ \ \ Legal execution by electrocution was introduced at the end of the nineteenth century, during the late Victorian era and at the height of the eugenics movement. New York had three prisons equipped with electric chairs capable of ridding society of significant numbers of those individuals deemed undesirable. One of the instrument's inventors called the device "the grandest success of the age." Although the new method of killing was never used as frequently as some policy makers would have liked, multiple executions often were conducted on the same night. Two, three, or four condemned convicts—oftentimes "rap partners," sentenced for the same murder—would go to their deaths in succession.\ Sing Sing's first electrocution was a quadruple one, involving Harris A. Smiler (a white bigamist and wife killer) and three other murderers: a black man, a Japanese sailor, and another white man. All four men personified various social and physical defects of the day. On August 12, 1912, a record eight convicts (six in one hour) were executed; seven were Italian immigrants, five of whom had been implicated in the fatal stabbing of Mrs. Mary Hall at the Croton Aqueduct, although another Italian man already had been executed for actually wielding the blade. Usually, the multiples consisted of pairs.\ The most famous executions involved Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, condemned by the United States government for atomic espionage at the height of the Cold War; Ruth Snyder, an adulterous blonde husband killer whose demise in 1928 was surreptitiously caught on film by a witness's hidden camera and later plastered over the front page of the New York Daily News; and Louis Lepke Buchalter, the reputed chief of Murder, Inc. (the forerunner of the American Mafia), whose underworld reign was finally ended in 1944 when he became the most powerful American gangster to be legally executed. Other condemned prisoners were equally notorious in their own time, but their fame has not lasted.\ Yet, many of those condemned were persons whose only claim to fame was the murder for which they were convicted. Some electrocutions apparently were so run-of-the-mill that they failed to attract any members of the press other than a regular reporter based in Westchester, who fed a standard account of the death over the wire service. Notice of some executions didn't even make it into the major city dailies, especially if the condemned man was black.\ Hundreds more prisoners at Sing Sing were sentenced to die but spared for one reason or another. (About a third of those condemned cheated the chair, and in later years the percentage of prisoners winning their appeals became so high that the legal machinery jammed and caused the executioner to cease production.) One of those saved — Isidore Zimmerman—spent 28 years in prison after his sentence was commuted. He ultimately was exonerated and released, but died before he could collect a penny from any judgment against the state. Salvatore Agron, alias "The Capeman," was reprieved by Governor Nelson Rockefeller and later became the subject of a Broadway show. But they were the lucky ones.\ Sing Sing's final electrocution, and the last legal execution carried out in New York State during the twentieth century, involved Eddie Lee Mays, a 34-year-old black man who was convicted of shooting to death a white woman on Fifth Avenue and ultimately was added to the list of electrocutions on August 15, 1963. Six years later, the last death row inmate was transferred away. Capital punishment fell into deeper legal disfavor and seemingly was abandoned. The fabled death house was converted to a visiting center, and the electric chair was consigned to a Virginia museum.\ Today, most New Yorkers are too young to remember much about their state's version of capital punishment. But since New York reinstated the death penalty in 1995 and judges sentenced the first defendant to death in 1998, a discarded relic has returned to use. Today's statute calls for executions to be performed by lethal injection—poison rather than electrocution—and Clinton Prison has replaced Sing Sing as the favored killing place. But Sing Sing's death house history remains alive in the faces in the mug shots and in other paper traces that officials unwittingly left behind.\ The following sample offers a look inside.

AcknowledgmentsIntroduction1Sing Sing10Death House16Arrival20Rules42Guards48Shrinks52Ties58Cases70Clemency80Escape Attempts86Stay96The Letter104Thursday114The Chair118Witness120Resistance126Remains132Settling Up138Prisoners Legally Executed at Sing Sing Prison147About the Author167

\ Library JournalFor the first time since archival records were opened in 1977, readers can take a tour of Sing Sing Prison's infamous death house. From 1891 to 1963, 606 men and eight women were legally executed there in the electric chair. These executions were carried out with the strictest security away from public view. Yet journalist accounts of some of the high-profile capital cases made Sing Sing famous the world over. Investigative reporter Christianson (With Liberty for Some) has compiled the mug shots and dossiers of 70 condemned inmates with pictures of their physical surroundings. The result is a slim volume of indelible impressions. Today, Sing Sing is an average New York State correctional facility. Executions are no longer carried out there, and its notoriety has been eclipsed by more dreaded prisons in other states. Sing Sing's legacy, however, will likely remain an important part of America's history of criminal justice. Highly recommended.--Frances O. Sandiford, Green Haven Correctional Facility Lib., Stormville, NY Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\\\ \ \ \ \ From the Publisher"This is a rare book—haunting fragments from the lives of men and women on their way to the electric chair. A moving and troubling epitaph for the guilty and perhaps the innocent."\ -William Kennedy,author of Ironweed\ "Simply by presenting excerpts from the state's own internal files, this book offers some of the most compelling evidence against the death penalty."\ -Mario Cuomo,former Governor of New York\ "A haunting experience. Combining the clinical virtuosity of an exhumation with the fascination of an archeological dig, it delivers a powerful intellectual message about the death penalty. Among the most vicious features of capital punishment are the veils of secrecy and forgetting with which we shroud the rituals of execution. Condemned tears away those veils and makes us take a hard, cold look at the human realities they try to hide."\ -Anthony G. Amsterdam,Professor of Law at New York University School of Law\ "Unusually intimate and powerful."\ -New York Times,\ "A slim volume of indelible impressions. . . . Highly recommended."\ -Library Journal,\ \ \