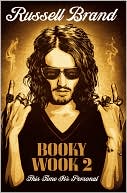

Cowboy & Wills: A Love Story

For Monica Holloway’s three-year-old son Wills, playtime, birthday parties, and preschool were torture. But within the first year of her son’s diagnosis with autism—the fastest-growing developmental disability in the U.S.—she and her husband found something that would raise her son’s confidence, elicit his very first belly laugh, and make other children clamor to play with him: Cowboy, a light blonde, brown-eyed golden retriever.\ Cowboy joined their family as an eight-week-old pup, suffering...

Search in google:

Christened "charming" and "winning" by the Washington Post and "touching" by Publishers Weekly, celebrated author Monica Holloway's deeply moving memoir shares the unforgettable story of an extraordinary little boy and the irresistible puppy who transformed his life. The day Monica Holloway learns that her lovable, brilliant three-year-old son has autism spectrum disorder, she takes him to buy an aquarium. But what Wills really wants is a puppy, and from the moment Cowboy Carol Lawrence, an overeager and affectionate golden retriever, joins the family, Monica watches as her cautious son steps a little farther into the world. With his new "sister" Cowboy by his side, Wills finds the courage to invite kids over for playdates, conquer his debilitating fear of water, and finally sleep in his own bed with the puppy's paws draped across his small chest. And when Cowboy turns out to need her new family as much as they need her, they discover just how much... The Washington Post - Carolyn See …charming. Wills is a sweet and beautiful little boy; the photographs here as well as the text prove it. Cowboy is exemplary in her goodness. The author is forthright and winning.

Chapter One\ The day after Wills was diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder, I took him for a ride to Ben's Fish Store in Sherman Oaks to buy a large freshwater aquarium. We picked up all the equipment; a ten-gallon tank, a filter, multicolored rocks to spread on the bottom an imitation pirate ship made out of clay, tacky neon plastic plants, a large rock with a hole in the middle for the fish to swim through, fish food, a small green plastic net, a special siphon with a clear hose on the end to clean the tank, and replacement filters. It totaled $462.84 — a high price that I could barely afford to squeeze onto my overextended Visa. I didn't care; my three-year-old had autism.\ We couldn't buy the actual fish that day because the entire aquarium needed to be set up, with the filter plugged in for at least a week before any fish could go into it.\ "What would happen if we bought one fish for him to look at right away?" I asked Ben, the owner, more for myself than for Wills. I didn't want to face an empty aquarium.\ "That fish would die," he said, at which point Wills began crying and cupping his hands over his ears to ward off the unsurvivable grief over the loss of a fish we hadn't even met yet.\ "We'll wait," I said, picking up Wills and balancing him on my hip. Then Ben, in full Goth regalia, helped us carry our booty to the car. It took three trips.\ Wills was elated, I could tell. His eyes were flashing that clear blue twinkle I only saw when he was really, really happy. Sometimes his eyes were more like mirrors, my image bouncing back at me. Those were the times I was most panicked, watching Wills recede so deep inside himself that I saw no way to grab hold of his tiny hand and pull him back to me.\ But when Wills was present, the world tilted toward perfection.\ I, like Wills, was thrilled with our fish store purchase. The aquarium would push back the grief I'd felt twenty-four hours earlier (and every waking and sleeping moment since), sitting in his therapist Katherine's office, hearing her say, "Wills has autistic spectrum disorder. He clearly possesses autistic traits, but at three years old, I hesitate to diagnose him more specifically. For now, we can assume he's under the autistic umbrella."\ It wasn't that the diagnosis was a shock; we'd dreaded hearing it ever since we first took Wills to see Katherine a year and a half ago. Even before I'd called her that first time, autistic indicators had been lining up with shocking accuracy: he was a clingy, anxious baby who hadn't hit a single developmental mark. He was terrified of strangers, on sensory overload every time we left the house, and he refused to make eye contact. But still, the diagnosis struck with the velocity of Hurricane Andrew. And then, even more devastating, was when I learned later that day that autism was a "lifetime affliction" — no cure.\ I placed the aquarium on a beach towel I'd spread out on the family room carpet and watched Wills pour the multicolored rocks into the bottom. He held the heavy plastic bag with both hands as the tiny stones pelted the glass, creating a huge racket — the kind that usually drove him to tears. He stopped for a moment and the noise stopped. He poured more rocks and the noise resumed. Wills looked at me.\ "It's noisy, isn't it?" I said. He hesitated, but then kept pouring.\ Already this aquarium was paying dividends. If Wills could ignore the clatter, then his overly tidy, more-than-slightly OCD mother could relax enough to tend an enormous fish tank with all of its gelatinous algae and floating poop ropes hanging from fish butts.\ I was hoping for something reliable and alive in the house.\ My husband, Michael, had no say in the fish undertaking because he wasn't home. He wasn't even in the same time zone.\ Michael had been working as a writer on a television show in Chicago for the past six months and, even though he flew back every other weekend for a thirty-two-hour visit, during which he was exhausted and distracted, and even though we'd made the Chicago decision together, it created a huge support vacuum.\ In my ugliest, most self-pitying moments, I clung, white-knuckled, to the notion that I was the helpless victim of a neglectful and absent husband. It was less devastating than placing my outrage and disappointment where it was warranted — on the gods who anointed my towheaded, blue-eyed boy with a life of autism — because the truth was, there wasn't anyone to blame. Still, thoughts of revenge ricocheted around in my head, looking for the culprit, worried, I think, that it just might be me.\ It was a fact that with all of the therapies Katherine said Wills needed, it would take plenty of cash to keep him moving forward, and for the first time in both our lives, Michael and I had some.\ When we first met, Michael was driving a taxicab while working on his writing career and I was a struggling stage actress, working as an office temp. Neither of us could afford health insurance, but we didn't spend much time contemplating that — we were enamored, consumed by each other, and young.\ Our finances were slightly better once we married, and I was hired as assistant to the executive producers of a reality television show and Michael began writing for a small animation company. But right before Wills was born, Michael's career took off, and as it turned out, just in time.\ So his job in Chicago was an enormous blessing. We had the money and insurance to help Wills, and I was free to be a stay-at-home mom, spending my days fawning over my darling son and trying to make him better. I knew how lucky I was.\ The only problem was how isolated I'd become. In a cross between Mommie Dearest and Girl, Interrupted, my family and I had parted ways. Only my sister JoAnn, who lived four blocks from us, and I remained close. This lack of family presence put a lot of pressure on Michael. With the exception of JoAnn, he was my entire extended family — mom, dad, uncles, cousins, aunts, sibling. It wasn't fair, putting that much pressure on him, but I didn't know that then. I was attached to my six-foot-five pillar of calm like paint on a barn, so when he temporarily moved, it was like losing my family all over again — only this time, a family I really, really loved — one who took care of Wills and me and loved us right back.\ JoAnn pitched in when she could, keeping us company and letting me out of the house once in a while, but she was extremely busy working in social services. Still, what a comfort it was having her so close.\ I pulled the aquarium filter out of the box and read the directions aloud. Wills looked at me, hopeful. "Place the plastic shelter-cover onto the rotating mechanism..." I looked at Wills, "We'll have to wing it," I said. I was lousy with directions. He nodded.\ Somehow we managed to get the filter working and for a week it hummed away in the fishless aquarium, the green and blue plastic plants sashaying in the current. Wills and I sat in front of it, admiring the cozy underwater environment we had created.\ "It's beautiful," I said. He smiled.\ "Daddy will like it," he said, watching the bubbles tumbling from the filter.\ "Yes," I said, "when he comes home, he'll love it."\ Michael had called to say that the show was a mess. He'd have to work on rewrites over the weekend and couldn't fly home. I was looking at another two weeks without a break, and still hadn't had a chance to process Wills's diagnosis, let alone discuss it in any depth with Michael. What would it mean for Wills's future and ours? Wills was autistic, and I couldn't change it. It was a fact, like the sun setting or the sum of two plus two. I'd let him down. Someone did.\ "I ordered monkeys," I told Wills, attempting a lame joke that just might work on a three-year-old. Wills didn't "get" jokes due to his concrete thinking, but Katherine had suggested I try some out on him. "I hope they fit in there."\ "Fish only."\ "In the aquarium?" I asked.\ "Fish." He looked at me confused, his eyebrows pinched together.\ "Oh, that's right, fish," I agreed. He nodded, serious and focused. "Mommy's only kidding, honey. I didn't order monkeys." He looked directly at me. "But wouldn't it be funny if I did? They'd be so much fun."\ "Monkeys don't live under there," he said, poking the glass.\ "I know," I said, giving up. "I was joking." Bombing was more like it.\ Wills had the misfortune of having silly parents. Michael and I were careful to keep our laughter under control, but nothing gave us more pleasure than cracking each other up. And this would send Wills into a screaming fit, pointing and yelling, "NO! NO!" The fact that laughter, such a vital part of life, was so disturbing to Wills was one of the cruelest ironies for this couple of born comedians.\ The quiet, the lack of fun, made Michael's absence even more profound. Where were the Frank Sinatra songs he played while cooking Swedish meatballs in his underpants? What was a Sunday afternoon without Michael's Mets game muted in the background so that the cheering (or, given that these were the Mets, sobbing) fans wouldn't upset Wills? I sat down and wrote my husband a love letter — one of many — except that he wrote more frequently than me. His were often just a couple of sentences scribbled on the back of a script, but sometimes he wrote on his legal pad. Those were the keepers. The letters were something I could look forward to, but they didn't have green eyes and wavy brown hair like Michael. Today I was needing the real thing.\ Still feeling fragile from Wills's diagnosis, the two of us stayed home all week with only the sound of the humming aquarium to keep us company — no weekly visit to the grocery store, no walks around the block, nothing. I didn't want to run into someone we knew who might ask how we were doing. I hadn't figured out an answer to that one yet.\ We found plenty of things to do. Wills loved wetting down our sidewalk with the garden hose. I'd help him pull on his green boots with the frog faces molded into the toes, and watch as he stomped around in his boots and diaper soaking the place. With all of the water gushing, everything was drenched — me, the grass, the Adirondack chairs, his plastic banana scooter — but Wills didn't get a single drop of water on himself. He was always pristine: no water, no dirt, no paint, no clay ever touched him if he could help it. (There were lots of rubber gloves at our house.) If his hands accidentally got dirty or sticky, he'd stand with his fingers spread wide, frozen in place until I picked him up under his armpits and carried him to the bathroom, where we'd wash away the offensive filth.\ Katherine and I hoped to make him more comfortable with messes. The only problem was, I needed the exact same help. My anxieties often manifested in my cleaning around the baseboards of our house at three in the morning, regrouting the bathtub while Wills napped, or obsessively picking up leaves in the backyard. Mindless, neurotic tasks, like lining up books on the shelves according to the color of their spines, seemed to be the only thing that brought me relief.\ The OCD had followed me through my teen years and had kicked into high gear when I began noticing that Wills wasn't holding his head up or crawling at the appropriate times. The longer the delay, the more I scrubbed. My son might not have been rolling over at nine months, but you could eat a four-course meal off my dining room floor.\ When I dreamt of being a mother, I'd pictured a completely different scenario. I was sure that immediately upon delivering my child, I'd become a carefree mom, napping when my son napped and carrying him around parks and zoos in an organic cotton sling. Instead, I hung over the edge of his bassinette like a scientist monitoring a petri dish and never once used the sling for fear of suffocating him in the folds of the rose-printed fabric.\ I was unsure about the difference between letting a child experience the world for himself and what constituted neglect. So I erred on the overprotective side. If JoAnn was over at the house and Wills cried, the two of us practically knocked heads together while rushing into his room and bending over his plushy blue-and-white crib with the Cow Jumping Over the Moon mobile to ease whatever excruciating pain he must have been experiencing — but it was usually just gas.\ Finally, the week of waiting was over, and it was time to pick out our fish.\ "We're ready," I told Ben as the bell on the front door of the fish store jingled. Wills was riding on my back with his soft, square hands tucked under my chin.\ "Excellent," he said, cracking his knuckles. "Come with me." He walked us down a dark, narrow aisle where the freshwater tanks glowed infrared. "You can choose any of the fish on this wall," he said, with a sweeping gesture toward the incandescent tanks.\ We peered inside each one, and Wills pointed to the fish he wanted.\ Ben suggested we start out with ten fish. "You'll probably lose a few the first couple of weeks anyway as your tank is getting acclimated. You don't want to overcrowd it."\ We were disappointed. We wanted at least twenty. With my son's future at risk, I didn't think there were enough fish in the store to compensate for my grief and ten was certainly not going to do it. But we listened to Ben and bought three swordtails, four neon tetras, two black mollies, and one small sucker fish to keep the tank clean. Traveling home in two clear plastic bags filled with water, they had just enough air to get them down Ventura Boulevard and into the house. Wills crossed one leg over the other as he settled into his soft, blue car seat, a plastic bag resting in his lap. The other bag was balanced on the cup holder beside me. Leon Redbone sang "Shoo Fly, Don't Bother Me," and I felt relaxed for the first time since I'd given birth. In the rearview mirror, I saw Wills patting the top of his plastic bag.\ We brought the fish into the house, took the lid off the aquarium, and floated them on top of the water for twenty minutes per Ben's instructions. "The fish have to acclimate to the temperature of the water," he'd warned us.\ Just when we thought we couldn't stand it any longer, it was time to open the bags and release them. With each blur of color, our aquarium became more alive. Wills and I sat on cushions in front of the tank and watched the fish explore their new home. It was oddly satisfying to have ten living things dependent on us. And unlike our lives, we controlled it all — the temperature, the environment, and the population.\ Wills checked the tank every morning to see how everyone was doing and fed them himself. When we found a fish floating on top — dead, slimy, and covered in white fuzzy death fluff — I'd lay it in a small cardboard jewelry box that Wills had decorated with colored sequins and bury it in the six-foot-by-four-foot garden we'd just begun working on behind our garage. The number of dead fish was directly related to the exorbitant amount of food Wills was dumping into the tank every day, so I began measuring it out for him into tiny teaspoons.\ After yet another burial, I looked down at my miraculous child who was squatting in his garden, concentrating on the back of a fern leaf, his eye pressed a little too close to his plastic magnifying glass. His patience and concentration were unmatched for a three-year-old, and as I watched him, an enormous swirl of hope encircled me. Autism was just a word, and for that one moment, the abject terror that had struck, paralyzing me over the last week, vanished. I had good reason to hope. Wills had a habit of surprising us. Sure, he didn't walk until he was sixteen months old, but when he did, he just got up and strolled into the kitchen as if he'd just remembered it was happy hour and the glasses needed to be chilled.\ I'd sat there dumbstruck. He padded back around the corner to see why I hadn't followed. I jumped up and hurried after him.\ He looked different standing on his own two feet. His back seemed so long and his diaper, comfy and snug around his waist, was bunched up in the back, with pastel pictures of Mickey Mouse leading an imaginary parade across his butt. I'd never seen it from that angle.\ After that, he walked everywhere, with me running around behind him, silently cheering.\ Wills, who'd been completely silent — no babbling or cooing — began talking the exact same way. JoAnn and I were outside a piano store when Wills, at seventeen months, pointed to a spigot and said, "Water." We screamed so loudly that he started crying.\ I picked him up immediately and said, "Yes, water. You are exactly right, that's where water comes from."\ He pointed toward the sky. "Airplane."\ I danced in place. "You want to see airplanes?" I asked him.\ "Airplane," he said, again.\ "Okay, let's go see some airplanes!" I would have taken him to Monte Carlo if he'd asked.\ I couldn't have been more thrilled. What I didn't know was that Wills's first fixation had manifested with a single word, "airplane." From the moment he said the word, it was impossible to get Wills to focus on anything else. Almost every day, he and I sat alone in the lobby of the tiny Van Nuys airport, Wills's face pressed against the glass, watching airplanes come and go. He clapped when they landed and waved bye-bye when they took off. Although Wills was usually unable to tolerate loud noises, the roar of the jet engines didn't faze him. He was happy there.\ I tried taking him to Balboa Park on the way home, where other children were running beside the lake feeding the ducks and playing on the jungle gym, but he was having none of it. It was either the airport or our house. He did like going to Barnes & Noble, where he'd pull out books with airplanes on the covers, and sit on my lap, mesmerized as I read about the construction of LAX or the Wright Brothers' first flight. His colorful board books with ducks and fire trucks on the cover sat in his blue bookcase, untouched. Soon after, his toy box began filling up with plastic airplanes complete with rubber wheels and tiny pilots with painted-on hats. Those were quickly replaced with miniature replicas of real airplanes. Wills wanted his toys to be authentic. Kiddie airplanes didn't cut it.\ Michael and I focused on how smart he was — how advanced. Who'd ever heard of a toddler sitting still for a history lesson in aviation? We were astounded by his ability to recognize airline names from the logos on their tails. Michael would take Wills to Encounters, the funky-looking restaurant in the middle of LAX, where he'd point to approaching aircrafts and pronounce in his shy whisper, "Japan Airlines...Alaska...Lufthansa...Qantas..."\ Wills was prodigious in other ways as well. He had an incredible facility for building things, creating forts, train stations, and airports (of course) out of stacks of videotape cassettes and blocks. He made himself a pair of glasses, just like Mommy's, asking me to cut the bottoms out of two Dixie cups so he could string them together using gardening wire. He sat on the front stoop, balancing them on his turned-up nose.\ But still, it was getting harder to ignore Wills's idiosyncrasies. Aside from his obsession with airplanes, Wills was extremely sensitive to textures and noises; a flannel shirt gave him "the goose bumps" and bubbles in the bathtub actually "hurt" his skin. The sudden bark of our neighbor's dog would send him running toward the back of the house, hands clamped over his ears, his face distorted in pain.\ Probably the most worrisome development was what his pediatrician, Dr. Todd, described as his "profound stranger anxiety." If we strolled by someone in the park and they bent down and said, "What a gorgeous little boy," his thrashing legs and ear-piercing screams sent his admirer bolting in the opposite direction.\ Still, there were times when he could experience new people and places without a fuss, like his first visit to Michael's parents' house. They lived in New Jersey and the five-hour flight to Newark went off without a hitch. Wills was unaffected by the other people stuffed into the narrow fuselage, the blast of the engines, or the sour smell of airplane food. He sat in his car seat, feet crossed, nibbling oyster crackers and telling us about the cooling system — as composed as Jack Benny delivering a joke.\ Michael and I were heartened, thinking that maybe he was outgrowing some of his anxieties, but then someone would inevitably come up to us in the park beside Michael's parents' house to say hello, and Wills would scream and run in the opposite direction. We didn't know what to think. I spent nights pacing and fretting and my days bugging his pediatrician for reassurance.\ One day when Wills was eighteen months old, my friend Jenn called and asked if she could drop off a book she had borrowed. I hung up the phone and looked at Wills playing with his blocks.\ "Jenn's coming over," I said. He looked startled. "I know you don't like visitors but she's really great."\ A few minutes later, the doorbell rang and Jenn was waving at me through the glass. I felt like the old me, the woman who yearned for company, throwing open the door to greet her; I couldn't wait for her to meet Wills.\ I turned to introduce them, but he was gone.\ "Hang on, Jenn, I have to get Wills," I said, following the trail of dropped blocks.\ The trail ended near his closet, where two red leather boots were poking out the door.\ "I see you," I teased.\ When I pulled back the door, he was sitting there, arms wrapped around his body, rocking back and forth.\ "Hey, buddy," I said kneeling down, "what's going on?"\ I looked into two completely blank eyes. Wills was not there.\ I tried to pick him up, but he scrambled farther back into his closet and clamped his hands over his ears.\ "Hang on, honey, I'll be right back."\ I ran out to the living room. "Jenn, I'm sorry, Wills isn't feeling well. Can we get together another day?"\ "Sure," she said, heading for the door.\ I forced a smile.\ "Thanks for stopping by."\ I closed the front door and ran back to Wills's room. He was behind a stack of boxes now, his soft blond head barely visible.\ "Jenn's gone, buddy. Can you come out now?"\ He couldn't.\ I could live with the shrieking in public. I could humor his obsession with airplanes. I could minimalize his sensitivity to sound and texture. But I could not deny that he was vanishing from me. I knew if I let that happen, I might never get him back.\ I sat in front of the closet with my hand stuck behind the boxes, touching his soft leg.\ "It's okay, buddy. Come out when you're ready. It's okay."\ The following morning I made an appointment to see Katherine. Michael and I told ourselves it was going to be okay. Katherine would say, "All children go through stages that are puzzling or not in sync with a doctor's expectation. There's nothing to worry about," but that didn't happen. It was both shocking and inevitable — my eighteen-month-old son now had his own therapist.\ Over the next year and a half, we did every exercise Katherine suggested — narrating his feelings for him, structuring his day so that there were as few surprises as possible, helping him make eye contact. But here we were at age three, and the diagnosis had come — autistic spectrum disorder. The very next day, we bought the fish.\ As Wills gazed at his new aquarium, the phone rang. It was Michael. I was in a wretched, Ihave-cramps-and-am-going-to-explode-with-water-weight-gain mood; tired, flabby, and temporarily single. It had been more than a week since the diagnosis, and I was an emotional yoyo. Depending on the day (or the hour), I'd go from thinking, Wills is a genius and everything's going to be fine, to How could this be happening? And the yoyo-ing wasn't just centered around autism, it extended to my unsuspecting husband — a love letter from me one day/an emotional sock in the jaw the next.\ "Our new neighbor asked me out on a date today," I told Michael.\ "What?" he asked.\ "I told him I was married and his response was, 'I've never seen anyone over there,' and I said, 'Exactly.' He thought I was divorced!"\ "I hope you turned him down." Michael laughed.\ "It's like someone snatched you away," I said.\ "I'm right here." It was painfully obvious how dependent I was on this man who made me so happy and was by far the most reasonable of the three of us.\ "You have no idea what's going on with your son."\ "I know what's going on," he said. "I talk to you every day. You tell me exactly what's happening. I hear you. I'm not just blowing it off." He was right. I regurgitated our daily routine like a bulimic after a binge.\ "Well, I'm glad you're listening," I said.\ "Don't you know how hard this is on me?" he fired back. "I miss both of you so much," his voice rising in pitch. "I'm missing out on everything."\ "Not everything," I said, trying to defuse what I'd sparked. "I'm rarely bathed."\ "I'd like to see you unbathed," he said, "I'd like to see you painted green — it doesn't matter how you look, Monica, I always want to see you and Wills. You know that."\ "I do know," I said.\ A long pause lay there, like a dead squirrel on the road.\ "I'm scared," I finally admitted.\ "I'm terrified," Michael said.\ "What if we can't help him?" My lips started doing that involuntary shivering thing — and then the tears.\ "We'll help him and, like Katherine said, he'll continue to improve," he assured me. "We love him so much. That's a good start."\ "I wish love cured autism."\ Copyright © 2009 by Monica Holloway

\ Carolyn See…charming. Wills is a sweet and beautiful little boy; the photographs here as well as the text prove it. Cowboy is exemplary in her goodness. The author is forthright and winning.\ —The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyWhen Holloway learned that her son had autistic spectrum disorder she turned to pets, from hermit crabs to hamsters to Ruby the Rabbit, rather than give up hope on reaching her son Wills, so traumatized by sensory overload that even a bath is an excruciating experience: hurtful bubbles followed the water's horrifying disappearance down the drain. Eventually Cowboy, a puppy with golden hair to match Wills's, arrives to bring the Holloways their first shining moments of progress: "Cowboy was... leading Wills into the world of his peers" Touching moments dot the narrative, but it avoids sentiment much as Wills would if telling his own story; at no time is the story overwhelmed by the inherent adorability of its subjects. Though readers may end up starved for intimacy, it mimics Holloway's own struggle-loving a child outwardly unable of returning it-and heightens his moments of connection. \ Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.\\\ \