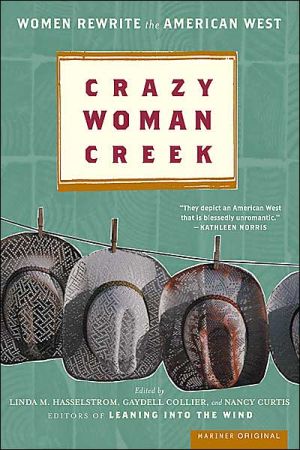

Crazy Woman Creek: Women Rewrite the American West

Crazy Woman Creek is a collection of prose and poetry about real women in the West and their connection to a larger whole. Long troubled by the misguided images of skinny cowgirls on prancing palominos, the editors embarked on a mission to set the record straight. They wanted these western women to reveal the realities of their lives in their own words.\ In Crazy Woman Creek, 153 women west of the Mississippi write of the ways they shape and sustain their communities. Whether these groups...

Search in google:

Crossing the eponymous Wyoming creek together in a truck one day, the three editors wondered why it is that memorable women in the Old West so frequently are portrayed as either insane, loose, or nameless. Their cure is this collection of bite-size prose and poetry by contemporary Western women telling personal stories about their connections to the West and the rest of the world. It's a tribute to the ordinary and the unconventional ways that women have shaped and sustained communities and contributed (often silently and namelessly) to the legacy of the West. The editors' third anthology of women's writing, it includes the work of 153 women from Nebraska Buddhists to suburban rodeo moms. Annotation ©2004 Book News, Inc., Portland, ORLibrary JournalThe editors and many of the authors featured in Leaning into the Wind and Woven on the Wind have reunited for another likable collection of essays and poetry featuring women of the American West. This hodgepodge is comfortable and folksy yet diverse. Where else can a reader find an essay by a Nebraska Buddhist followed by a poem recalling "Vagina Dialogues on a Road Trip"? Themes emerge throughout the collection-how women minister to one another with food and a helping hand, how laughter heals and protects, and how vitally important relationships are to women, especially to those living in remote areas. Many selections are heartwarming, some are chilling in their truthfulness, and many demonstrate the necessary humor of survivors. Recommended for public and academic libraries with regional collections.-Jan Brue Enright, Augustana Coll. Lib., Sioux Falls, SD Copyright 2004 Reed Business Information.

Introduction: Beyond Crazy Woman Creek\ \ "We celebrate community and stories."\ —Jane Kirkpatrick\ \ One hot day not long ago, the three editors of this collection were bouncing \ along a two-lane highway between Recluse and Story, Wyoming. One of us \ was driving; we all own beat-up SUVs with enough cargo space to haul the \ boxes of books and fliers we take to readings. The windows were down, so \ we inhaled the zest of sagebrush and tasted the difference in dust from \ plateaus or creek bottoms. Two of us visited in front while the third, nesting \ among our luggage in the back seat, leaned forward to make remarks.\ \ The tires rumbled as we crossed a bridge. "Crazy Woman Creek," \ one of us snarled. "Why isn't it ever Samantha Wilson Creek?"\ "Or," said the beautiful and brilliant editor, "Wonderful Woman \ Creek?"\ "Or even," said the serious one, "First Woman Doctor Creek."\ "Strangers must think all the memorable women in the Old West \ were nuts," said the cynical one, "or prostitutes like Mother Featherlegs."\ "Or nameless," said the thoughtful one. "And what does that tell \ you about the men who did the naming?"\ "My home state was just full of places with 'squaw' in the name \ until pretty recently," said the one from South Dakota.\ "And Wyoming still has those little sharp-pointed hills called \ Maggie's Nipples," said the one who collects maps.\ "Squaw Hill, Old Woman Creek, Crazy Mountains," mumbled \ somebody from the back seat.\ "Is anythingimportant named after ordinary women?" said the \ exlibrarian. "Like rivers or mountains? Are there any memorials to women \ homesteaders?"\ "I guess you could count the Tetons," said the one who shoots a \ muzzle loader, "thanks to some lonely French fur trapper; they never looked \ like breasts to me."\ "My grandmother," mentioned the oldest one, "always said a \ decent woman's name appeared in public only three times: at birth, at her \ marriage, and at her death. I guess our tombstones are supposed to be our \ monuments."\ "The good news is, we have to die first," snapped the grouchy one.\ \ "What knits us are the rhythms of our female lives."\ —Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer\ \ Nearly everyone has a favorite, and different, image of the West, where myth \ and reality gallop into the same sunset. Maybe you had to be crazy to settle \ here, especially if you were a woman. Both legend and history record \ extremes in temperature, elevation, snowfall, drought, fire, and flood. Lyric \ and chronicle celebrate courage and cowardice, profusion and famine, beauty \ and monotony, peace and lawlessness. Pioneers heading west from Europe \ or the Eastern states were often called lunatics by their relatives.\ Conflict and change are inherent in the West, though Westerners \ are perceived to be mostly honest, hard-working, independent lovers of \ freedom, who are tough or tender, depending on the need. Westerners are \ renowned for building friendly settlements in the middle of hardship. This \ book stands solidly on a tradition that cherishes paradox. The editors of \ Crazy Woman Creek think women furnished more to the Western character \ than their labor feeding campfires and rearing children. So why weren't more \ mountains, statues, or government buildings named for women?\ Perhaps Westerners thought anyone could do women's work, and \ maybe some of us accepted that judgment. The contrary West has always \ had room for both the minister's wife and the mistress; sometimes they \ worked together toward a common goal. And maybe naming features of the \ landscape after shady ladies is further evidence of the puzzle that is the \ West.\ Many modern Western women, including some of the writers of \ this collection, still live remote from what passes for modern civilization, but \ they are also part of a cooperative community. Like their foremothers, they \ work hard, respect themselves, and can laugh at their mistakes. They may \ burst into song in the middle of a cattle drive or turn the air blue with curses \ while fixing a flat tire. Outrageous behavior may be the key to survival; our \ history sparkles with tales of women who prevailed because they were \ unpredictable enough to outsmart the bad guys.\ Westerners have always admired these crazy women, knowing \ that every good idea was once considered mad. Near my home, a statue \ celebrates Esther Hobart Morris, the first woman judge in America. Wyoming \ was still a territory when Esther joined a group of women who had the \ outrageous idea that they should be able to vote and hold public office; \ woman suffrage passed here in 1869.\ Still, modern Western women are tired of being nameless. Crazy \ Woman Creek presents ordinary women from west of the Mississippi River \ telling personal—and true—stories about their connections to the rest of the \ world. The writers in these pages accept some traditional Western views and \ renounce others. Carving their own images on the land in deed, word, and \ thought, they are rewriting history for all of us.\ \ "We are most aware of the inevitable tug of time."\ —Sarah Byrn Rickman\ \ This collection of writing by contemporary Western women is a conversation \ in prose and poetry for readers and writers. Modern Western women keep \ house, do outside chores, haul children and horses to 4-H meetings and \ rodeos. They learned from their mothers and grandmothers, but they are also \ absorbing new ideas: how to hold a job in town, or travel the Internet as well \ as gravel roads. Their work has rarely been acknowledged publicly or \ permanently. A bawdy-house madam was more likely to be remembered in \ myth and on maps than an ordinary housewife, but both were overshadowed \ by male adventurers who wrote the history books. This book is one way to \ recognize the ways women have shaped and sustained Western \ communities and contributed, sometimes silently, to the true legacy of the \ West.\ Crazy Woman Creek also portrays the new story we are writing, \ as strangers move West to inhabit the land differently. As a contributor to \ this volume notes, "What each of these groups can't see is that at the core, \ they . . . love the same place and want the same thing." (Unless otherwise \ credited, quotations in this introduction are from contributors' writing in Crazy \ Woman Creek.)\ We may not always realize or acknowledge the likeness, but \ each individual is linked to every other by similar experiences, interests, \ attitudes, and beliefs. A crisis may bring us together, but it is easy to forget \ those bonds when our opinions clash. These days, "the natives . . . are a \ little bitter" toward "the newcomers, 'those damn environmentalists.'" Old-\ timers wonder, sometimes in loud outrage, what will happen to the \ neighborhoods we have cherished. We are afraid that as the places change, \ we will lose the values we esteem—honesty, friendliness, self-sufficiency, \ moral courage.\ The Native Americans probably said the same things as \ immigrant wagons rumbled across the buffalo grass—yet the descendants of \ people who bickered and brawled in different languages are now accepted as \ native Westerners. We think the true stories in Crazy Woman Creek will \ continue to inspire intelligent conversations about community.\ In the Old West, both men and women sometimes used force to \ get their way. Though we favor peaceful negotiation, we don't want to forget \ those tough old broads rudely memorialized in our place-names. Moving \ beyond Crazy Woman Creek doesn't mean forgetting their legacy. We'll offer \ new neighbors coffee and banana bread. But if some newcomer doesn't think \ the name Maggie's Nipples is politically correct, we might resist changing \ the name to Margaret's Mammaries.\ \ "Until we find meaning in the stories of our lives, we're destined to wander in \ the wilderness, even though we're in a promised land."\ —Jane Kirkpatrick\ \ We three editors have known one another for more than twenty years. \ Collecting writing by Western women in two previous anthologies taught us \ that "we could count on each other," and working together has made us \ friends.\ Gaydell, a librarian before she retired, writes and operates \ Backpocket Books from a small ranch near Sundance. Nancy helps manage \ the family ranch near Glendo and directs High Plains Press, publishing \ books about Wyoming and the West. Linda lives in Cheyenne and owns a \ South Dakota ranch where she conducts writing retreats for women.\ All three of the anthologies we have edited together, including \ Crazy Woman Creek, grew out of the Western landscape and the women \ who inhabit it. During the past decade, the editors have driven thousands of \ miles together, speculating about how each collection might develop, while \ discussing a zillion other topics. When we traveled to promote the books \ through readings and autograph parties, we inevitably came home feeling \ invigorated.\ Our first partnership grew out of conversations about strong \ women who helped form the Western communities where we grew up. We \ encouraged women from six Western states to tell us how they survived in \ troubled times. Though we'd heard these stories all our lives, we weren't sure \ women would reveal them to readers who live mostly in cities. Would urban \ dwellers appreciate these Western truths?\ Western women sent a stack of submissions taller than any of \ us, proving that the tough, shrewd women of the real West aren't all in \ cemeteries as hard to find as the Mother Featherlegs Monument. (Yes, she \ was probably a prostitute. Local cowboys nicknamed her for the lacy red \ pantaloons she wore tied at the ankles when she rode her horse to town, but \ they seemed to respect her for her grit rather than her profession.)\ Teamwork created Leaning into the Wind: Women Write from the \ Heart of the West. Making our selections on the basis of authenticity and \ quality, we chose 246 essays and poems contributed by 206 women. Some \ of them had never before written for publication, but they were—ah—crazy \ enough to trust us.\ Thousands of books sold before the official publication date, \ thereby demonstrating that we'd found readers as well as writers. The \ publication party at Devils Tower, Wyoming, in June 1997 created legends. \ Mindy, an assistant editor for Houghton Mifflin, came from Boston a few days \ early to meet us, donned a Western hat, and staunchly ate Rocky Mountain \ oysters at a ranch branding. (She later moved west.)\ \ "A small community . . . is a microcosm of the larger world."\ —Marcia Hensley\ \ On the day of the celebration, we waited nervously at the foot of Devils Tower. \ As contributors arrived, we handed each a complimentary copy. A gray-\ haired woman in a red Western suit and riding boots stood a little taller as \ she said, "It's a real book! I thought it would be mimeographed or something!"\ Men leaned on pickups in the parking lot; a father and his children \ watched deer in the meadow; grandmothers played with babies. At picnic \ tables in the shade, the contributors read, talked, and signed books. More \ stories prompted "laughter as we heaped our plates" with a meal provided by \ the Crook County Cattlewomen. A local woman served three huge cakes; \ one was decorated with an image of Devils Tower, one with a cowgirl, and \ one with the book title.\ A new association that began to form around the book set the \ pattern for all three collections. "As subtly as the snow melted into the land, \ our lives began to melt into the community."\ Since we were in Wyoming, the wind was blowing; we duct-taped \ a box of tissues to the podium, and many women used it as they read and \ told stories in strong or halting voices. A guitarist sang during intermissions, \ while the audience limbered up and collected autographs. The reading lasted \ seven hours, but no one complained. After driving several hours to get there, \ ranch folks left early, knowing they would have to do chores in the dark. \ Some of us were reminded of small-town picnics long ago; others, younger or \ more urban, had never seen anything like that day.\ What would such a gathering have been like in Boston? we asked \ our East Coast editor. Less open, less warm, she said; "the women would \ have worn less comfortable shoes and tried to stand by the most important \ person."\ Part of the story of the book's creation ended that day, but our \ lives had become entwined with those of our contributors and readers. Many \ of us keep in contact, weaving more narratives from the connections we \ formed, or strengthened, at Devils Tower. Contributors come to read with us \ everywhere we go; they write books and encourage other women in \ community efforts. Leaning, they say, validates their struggles, encourages \ them to defend their beliefs. Readers elsewhere realize that these Western \ women have opinions that must be considered in decisions about the West. \ Dozens of readers tell us they keep the book on their bedside tables, so they \ can reread favorite parts.\ Some reviewers didn't realize that the book was written by real \ women about the hardships and joys to be found in today's West. Befuddled \ by their own myths, they asked whether these stories by "pioneer women" \ were really true.\ That night, when we editors collapsed, we were already thinking of \ the next anthology. A reader later wrote, "This isn't a book. It's a communion."\ \ "Our lives are a song of communities."\ —Kathryn E. Kelley\ \ As usual, the editors drove around the West promoting the book. Thriftily, we \ shared motel rooms, discovering that Gaydell writes at sunrise, eats leftover \ Chinese food for breakfast, and always packs chocolate; that Nancy takes \ her own coffeepot; that Linda doesn't own a hair dryer. At each stop, we \ greeted "women we had just met, yet knew to our bones because their \ stories were our own." Although our opinions sometimes differed wildly—on \ religion, politics, or agriculture—we found ourselves linked by shared \ experiences, our worlds expanding with each new acquaintance.\ While those first contributors are part of a unique Western \ population, each is also linked to others in an expanding spiral of influence. \ Our journeys create widening circles of connection, "interwoven communities" \ of people who know one another's friends or relatives or home neighborhoods. \ How many circles, we wonder, swirl around each of us?\ As we editors learned to appreciate and trust one another more, \ we began to talk about women's friendships. We asked one another: What \ do other Western women value in their friends? The theme of our second \ anthology, Woven on the Wind, had materialized.\ \ "I see the process at work—the connections that I did not see and could not \ value before."\ —Barbara Jessing\ \ In Leaning into the Wind, contributors wrote about their work, their dogs, their \ husbands, their work, their horses and goats, their children, work, the \ weather that complicated their lives, and work.\ For the second book, we asked them to write about the one topic \ they'd avoided: other women. Who were their friends, and why? If they had no \ women friends, how did they persevere? We feared that comradeship \ between women might be too private to publicize, but we were wrong; "in \ spite of the hard work, or maybe because of it, we found time for fun and \ friendship."\ Women from sixteen Western states and three Canadian \ provinces told us stories of friendship both fulfilling and disappointing. From \ more than a thousand manuscripts, we selected essays and poems by 148 \ women. Houghton Mifflin published Woven on the Wind: Women Write About \ Friendship in the Sagebrush West in 2001.\ Tattered Cover, Denver's legendary independent bookstore, \ generously hosted our May publication party during a typical plains spring \ blizzard. One writer snowshoed several miles from her mountain home, \ hoping to hitch a ride—only to find the highway blocked by drifts. Still, \ dozens of women gathered with our new editor from Boston to read and \ celebrate. Later, in a newsletter, we joyfully shared the warm reviews with our \ contributors, strengthening and deepening our bonds with one another. The \ writing "carries the weight of a communal essay," said one well-known writer, \ on the book's jacket. Women who live a long way from bookstores and malls \ exchange copies, celebrating friendship the way our forebears did when they \ helped each other butcher a buffalo or stitch a quilt.\ \ "Telling stories. Keeping faith."\ —Mary Sojourner\ \ A community of women has arisen around the three anthologies. With each \ new project, we refreshed past acquaintance and found new writers. These \ strong women "nurture not only their families but also their communities," \ and, like the books, will help preserve the truths of real Western lives for our \ future.\ So the theme of the third collection arose naturally from the \ writing and connections created by the first two. We believe, with many of \ these writers, that women who can lead are no more important than women \ who follow: women who clean the churches, make sandwiches for firefighters \ and for mourners at funerals. We understand that "as a group, we are \ leaders." On occasion, it is appropriate to act alone, but sometimes \ our "power to be heard comes through community, not individuality." These \ books are one way that Western women, some of whom came here from \ other parts of the world, have united to provide support for one another and to \ make their voices heard.\ We drove all over Nebraska, Colorado, the Dakotas, Montana, and \ Utah to promote Woven, and meanwhile we discussed ideas for a third \ anthology. We met contributors and readers in bookstores, county libraries, \ museums, coffee shops, book festivals, and in a huge concrete bunker that \ was once an underground water tank but now serves as an art center. \ Everywhere, we joined a "convergence of women."\ We'd planned to meet a Nebraska writer for lunch but arrived late, \ to .nd her family's feed store locked. At the local hotel café, a waitress said \ the woman usually ate lunch at home, and gave us directions. We chuckled \ at the familiar way a neighborhood keeps track of its residents.\ In Billings, Montana, we read with contributors on the sale floor of \ a cattle auction barn. Many in the audience had never entered a sale barn \ before, so one contributor's husband, an auctioneer, conducted a mock sale \ to show how such sales proceed, and to start the performance. We \ explained that the entire floor of the ring—freshly washed for our \ appearance—is a scale that weighs the livestock as they are sold and \ flashes the total onto a large screen, to help buyers calculate their bids. We \ thanked our hosts for turning off the scale, so that our combined tonnage was \ not revealed to the audience.\ \ "And once we started speaking out, we were never silent again."\ —Mary Zelinka\ \ Crazy Woman Creek collects 158 selections in prose or poetry from 153 \ contributors, portraying diverse communities in twenty-one states and one \ Canadian province, all west of the Mississippi River.\ From the rainy mountains of Oregon to the cornfields of Iowa, from \ the wheat fields of Saskatchewan to the arid plains of Texas, we solicited \ women's writing. For the first time in this anthology series, we relied on \ technology, e-mailing our call for manuscripts to twenty-two states, Mexico, \ and Canada's Western provinces. We flung our electronic message out to \ thousands of individuals and organizations focused on writing, reading, \ storytelling, journalism, rural life, the West, women's studies, and other \ fields; to radio stations, newspapers, magazines, publishers, and \ bookstores; to state and regional arts councils, extension services, and on-\ line discussion groups. Nearly four hundred women responded, sending us \ almost seven hundred answers in the form of essays and poems.\ Though writers were not allowed to submit their contributions by e-\ mail, we did ask for and receive some submissions on computer disks; in \ certain cases, we were able to transfer documents directly to our own \ computers without having to retype them, one of the time-devouring chores of \ the earlier books. We also worked with some writers on their manuscripts by \ e-mail. We met to discuss the anthology only once and conducted the rest of \ our business electronically, despite computer gremlins and outages caused \ by floods, blizzards, Wyoming wind, and fire.\ We cannot say that "we never left anyone out," but we are grateful \ also to the women who submitted pieces we are not able to publish. Their \ thoughts helped shape our perceptions of this book, and their writings \ inspired agonizing debates. Our most difficult task was deleting pieces we \ relished, in order to adhere to our contractual word limit.\ We delight in the diversity of these texts. Women whose lives \ differ from ours demonstrate that the West is no fantasy paradise where \ everyone dresses, votes, and thinks alike. As editors, we must present the \ truth, because we answer to our contributors. Some of these women are \ downright cantankerous!\ As in our two previous collections, in Crazy Woman Creek we \ allowed submissions to determine content and organization, and we might \ have created several other books from the available materials. As one \ contributor writes, "making community is like making rag rugs: it requires a \ lot of stitching-together, a decision not to regard any one scrap of fabric as \ essential to the design." Every one of us, and all the brilliant things we say \ and write, are merely scraps in a crazy quilt. Remove one of us, ten of us, \ thousands of us, and the design will change, but the creation will be braided \ anew, the gap filled by another rag or ribbon, so that the community remains \ strong and beautiful.\ \ "People opened their arms . . . gathered us in."\ —Phyllis Dugan\ \ In "Women Driving Pickups," the writers focus on spontaneous community, \ groups likely to gather without regular meeting dates, agendas, or officers. \ Many of these true stories involve a change of perspective: an Alaskan town \ hosts Vietnamese refugees; a "posse of lesbians" helps a newcomer; San \ Francisco commuters ignore their squabbles to rally around a larger issue.\ Sometimes, cooperation converges on need: a village in \ Washington conspires to keep a retarded woman safe; Canadian women \ provide food baskets; a hippie mother in California creatively supports her \ local library; an Afghan and a Mormon help a new mother of twins. Some \ women meet in a hot tub to visit, others in pickups or laundromats; a rancher \ reports on the reactions of cowboys when she chooses horse work over \ housework.\ The title was inspired by Ashley Coats's essay. This part of the \ book reflects, metaphorically as well as realistically, that "surge of \ understanding" which may flash between people even when they seem to be \ speeding down the road in separate vehicles, going different directions.\ \ "A unity of women."\ —Grace E. Reimers Kyhn\ \ "Hallelujah and a Show of Hands" centers on organized groups, men and \ women who meet at set times for a specific purpose. Contributors tell stories \ of the past and present, and sometimes they consider the future. Here, too, \ are women impatient with the restrictions of organized groups, women who \ want to "effect change rather than discuss it," who urge us to "get off the \ Internet and into the streets." An assortment of societies function or fail in \ these pages: a New Age commune, gatherings of Buddhists in Nebraska, \ Benedictine nuns in Colorado, and Hutterites in South Dakota. One writer \ describes how women ran a Wyoming railroad, until they lost their jobs when \ the men returned from war. Women recall harmony found at the drugstore, at \ the beauty parlor, at a powwow, in a sewing circle. Groups cooperate in \ running races and in saving a historic meeting hall, meet to discuss books or \ write them, to ride horses, organize funerals, support rape victims.\ We found the title in Helen M. Wayman's droll look at a group of \ church women confronting change, the poem "Hallelujah! Faith Circle!" The \ bickering "Lutern" women behave in pretty standard fashion for the West, \ resisting transformation as long as possible—but they also persist until they \ reach a compromise.\ \ "This twist of women, Bonded by our hands, Our hearts."\ —Lora K. Reiter\ \ "Cowgirl Up, Cupcakes" recognizes that whereas we seek membership in \ some groups, other societies select us. Though the choice of fellowship may \ not be ours, we often find possibilities we hadn't considered. These writers \ find humor, despair, admiration, or hope in characters tossed together by \ circumstance or genetics.\ Contributors write of those who build on painful experiences to \ create joy and who learn to relish the eccentricity of neighbors they never \ would have chosen. Others scrutinize their families, musing on benefits and \ obligations gleaned in weeding the garden, harvesting food, teaching an \ appreciation for language, or "doin' for the less fortunates."\ The writers discover communion between saints and spirits in a \ cemetery; between a hospital patient and the nurses and aides who care for \ him; among strangers who rally around a cancer patient; between women \ who are addicted to gambling. Women write of the opportunities inherent in \ the natural cycles of birth and death, health and illness. Time and memory \ connect the five-year-old helping her grandmother make tortillas to the \ grandma passing down tortilla lore. Embracing age, women tell how they \ learned to create their own companionship. In crises, these women have \ found an astonishing array of avenues for supporting one another.\ The title emerges from Ellen Vayo's story about the efforts of her \ mother and the Ladies of Charities to combat hardship after World War II. \ When times were tough, these women didn't put up with whining, but their \ efforts left a legacy of laughter and toughness their children remember and \ practice.\ \ "How does a community originate?"\ —Judy Ann\ \ This book began with the real West and its women, and with writing collected \ in the two previous books, both published by Houghton Mifflin. Instead of \ erecting monuments, the writers in these pages demonstrate community \ connections in story form. We expect the books to provide inspiration for our \ descendants a lot longer than the average fad does, whether it's a trendy \ bestseller or a marble obelisk.\ Traveling together, the editors admired miles of countryside, saw \ hundreds of Real Estate for Sale signs, and noticed malls and subdivisions \ attempting to encircle small towns. "Like the View?" says one sign; "Buy it!" \ We discussed the idea that anyone can own nature and asked how this trend \ will affect the Western communities where we live and work. Moseying along \ in Flora the Explorer, spitting dust, we pondered the future of Westerners and \ wannabes in city and country and began this third collaboration.\ After all, "woven inside women's ways of knowing" are centuries of \ survival in spite of tragedy. Whether we live in a subdivision or on a ranch, a \ logging hamlet or a tourist burg, we want to be in a place where neighbors \ mourn one another's losses, help each other build new lives, work together to \ resolve conflicts without rending the fabric of the neighborhood. When we \ succeed in identifying with fellow citizens, "the community wins," and we all \ benefit.\ Crazy Woman Creek became a wild and crazy gathering of \ viewpoints as complex as the Western landscape and the women—and \ men—who inhabit it. Contributors may contradict each other, but they \ manage to get along as well as folks ever have in the West.\ As traditional Western communities are subdivided and expanded, \ we wonder if new residents can ever settle comfortably into old \ neighborhoods. To do so, they must banish the myths and see the reality, \ understand that such places are not static photographs of folks in big hats on \ horses. We have all seen what one contributor describes as "the ugly face \ this normally friendly little town can wear." We know that Western \ communities, like gatherings of people anywhere, can be bleak or cozy.\ All three of us editors have lived most of our lives in the kind of \ traditional rural neighborhoods described by some contributors in the writings \ that follow. We recognize and love "that hometown sense of belonging, that \ like-mindedness" some writers report in the pages to follow. But through their \ writing we've also met women whose backgrounds are entirely different from \ ours, whose only bond to the land was their grandparents' reminiscences \ about farm life. They, too, speak in these pages; they care deeply about the \ West and want to belong. Have they arrived too late? We hope not.\ Some of these writers argue that a community can exist only in a \ particular place and must be composed of people who knew your \ grandparents and your parents. In many ways, we identify with this opinion, \ as can many Westerners who grew up in the sheltered assurance of a long \ and settled family history. But most of us can no longer expect our families \ to live in one place for several generations.\ Are our lively Western communities doomed to exist only as \ brown photographs of a flat landscape in a dusty book? Will future residents \ see the West through sepia-toned spectacles?\ The stories and poems in Crazy Woman Creek offer lively and \ varied views of the ways people come together in today's West, and ideas \ that may help us take a fresh look at the idea of community. Perhaps \ members of Western communities can create new ways of living together in \ settlements where residents accept the past as well as the future. Those \ rural settlements where we grew up were founded on the belief that "being \ part of a community is much more than owning property within its \ boundaries." Like several other contributors, we don't think that idea is \ obsolete.\ As other writers note, bemoaning our losses and hating \ newcomers do not improve a community. If folks who can't stand change just \ move away, they alter more than one neighborhood. Some women write \ about the challenge of staying in one place, adjusting as it reconstructs \ itself. Even when we feel most powerless, they say, we are not alone. An \ Idaho sheep rancher, for example, figured out how to educate newcomers, \ instead of cursing them. She now says, "In our community, we are all making \ new friends."\ Can neighborliness survive even as our landscape is being \ bulldozed and paved over? Before we can answer that question, we need to \ get acquainted. In order to participate as members of any community, we \ need to exchange our stories, to teach, and to learn. In this book, some \ women write guidelines for retaining or re-creating the best qualities of old-\ time Western neighborhoods.\ Everyone knows parables that can show us a path when we are \ lost, can heal us, recall us to our best selves. Telling stories from our lives, \ say the experts, helps us understand the events that have happened to us, \ no matter how difficult they have been. Sharing our burdens may assuage our \ loneliness, allow us to support one another without self-pity.\ Will getting to know our neighbors help us arbitrate a better future \ for our communities? We cannot keep our settlements forever in the past, \ though our mothers may have lived and died on the banks of Crazy Woman \ Creek without complaint, and without considering the implications. But if we \ invite a new neighbor in for a visit, or help him change a flat tire, we might \ begin to help people in our neighborhood decide together how much change \ we can accept. Newcomers and longtime residents may learn to live in \ peace, even if compromise means we must change Bitch Basin to Mountain \ Meadow Estates.\ One contributor remarks, about a tragic story told and retold in her \ town, that "we needed to draw the suffering of our neighbors into our lives and \ to claim their pain before we could begin to heal as individuals and as \ community." Repeating such a story, she implies, is not merely gossip, but a \ way of learning about each other, one that leads to the discovery of how \ much we have in common. Human nature tugs us toward one another. To \ determine the best possible future for Western settlements—or any other \ neighborhood—we need to get closer than we can by cell phone or a distant \ wave through the windshield.\ Another woman writes that she felt isolated in precisely the kind \ of subdivision many rural residents fear will replace our wide-open \ spaces. "Suddenly, community mattered," she writes. Searching for \ connections, she recalled how her mother and grandmother took casseroles \ to the bereaved and listened to their sadness. At first, she felt awkward \ copying her elders' gestures; she thought, "Maybe if I practiced, I would get \ better at it." And she did.\ Creating connections requires work, commitment, and time. Just \ moving in isn't enough; membership in a group or community has value only \ if it is earned in those countless rituals that make up our busy days. Offer a \ lift to a neighbor, visit with the pharmacist; small gestures splice us together, \ weaving bonds that become friendship and cooperation. A resident of a \ unique Iowa enclave says, "Those who stay and prosper are the ones who \ come to cherish Amana for what it is. They join in, take part, and help out." \ Any group could benefit from such involvement, as could the people who \ choose to participate—a mutual benefit.\ \ "There is no power struggle here; we are all givers."\ —Judy Ann\ \ Like the two collections of writing that preceded it, Crazy Woman Creek: \ Women Rewrite the American West has been created by its contributors. \ We asked women to draw upon their experiences living west of the \ Mississippi River, to write a good and true story about contemporary women \ in any community, whether it's a place, an organization, or a spontaneous \ gathering. Although men were not excluded, we wanted stories focused on \ women, and on how their actions affect others. Our yardstick would be, as \ always, authenticity and quality of writing.\ Evaluating manuscripts, we were alert for writing that grew out of \ strong convictions, whether we agreed with the conclusions or not. If a \ particular subject drew the attention of several writers, we worked to eliminate \ repetition and to select the most appropriate account. We loved brilliantly \ written compositions, but we also appreciated the work of less experienced \ writers whose beliefs and emotions were an important component in the \ collective voice. We asked ourselves how to balance prose and poetry, how \ much attention to pay to geographical distribution. Eventually, we agreed, the \ true stories we chose had to possess a quality we call heart.\ \ "Listen up sister."\ —Sureva Towler\ \ Historical legends recounting the source of the name of Wyoming's Crazy \ Woman Creek, running through the wild north-central region, are published at \ www.travelwyoming.com, but local chronicles are more informal and more \ vivid.\ One Wyoming writer told us that when the family crossed it, her \ husband always said, "Look, kids! There's your mom's creek: Crazy Woman \ Creek." He encouraged their kids to call it "Mom Creek." She's not married to \ him anymore, and she grits her teeth when she tells that story.\ Margaret Smith, who lives near the creek, tells us that after the \ crazy woman of legend died, her spirit inhabited the canyon walls. "For many \ years, people in the region could point to a woman's face in the rocks," she \ says. The woman looked as if she were crying—or screaming.\ Jane Wells, a contributor to this anthology, also lives nearby, and \ calls Crazy Woman Canyon "a monument of tumbled granite, rushing snow \ melt, deep shadows, and brilliant sunlight."\ Perhaps the canyon has become a cenotaph to one woman driven \ mad by grief, and the tales of today's inhabitants are fitting honors for all the \ nameless women of the West. Recalling the legends, keeping the stories \ alive can remind us of the power we women share.\ Every winter day, Jane Wells leaves her bed before dawn and in \ the moonlight pitches hay to the horses, breaks ice in the creek with an ax, \ and does other ranch chores before heading to her day job in town. She's \ standing behind the information desk at the museum when some tourists \ from Germany ask if she knows the origin of the name of Crazy Woman \ Canyon.\ She takes a deep breath and looks them straight in the eye. "As a \ matter of fact," she says, "I do. It was named after me." That's the attitude \ represented by this book.\ \ "Start learning now how to make community."\ —Lisa Heldke\ \ A Western woman might be independent enough to kiss a bull or brave \ enough to tickle a bear, and she tells her own stories. She is part of the \ tradition that produced Crazy Woman Creek, but she's rewriting the West \ with her words as well as her actions.\ If you can't see women in your neighborhood who are creating \ community, look in the mirror. "You will be held accountable," if not by \ others, certainly by yourself. Community requires you "to be your sister's \ keeper, to accept aid when you need it, and to offer help when it is your \ responsibility —woman to woman." One contributor reminds herself, "A \ simple, hand-prepared meal is one way back to oneself. I need to remember \ this." Let us all remember.\ Another contributor asserts, "One of the great myths of our age is \ that community is something you belong to, not something you work for." \ Why shouldn't the principle apply in families, in city neighborhoods, \ anywhere? Simply moving our belongings is not joining a community. Being \ at home requires us to contribute.\ Many of us in the rural West, as elsewhere, have "learned that to \ live near each other meant more than just sharing an address. We also had a \ responsibility to each other." Being responsible to one another can work in an \ apartment block, in a subdivision, in any group. Several writers focused \ precisely and movingly on "the price we pay for alienation and disconnection, \ the price we pay when a community shuts its eyes. "We've all seen \ examples of this particular expense in our communities.\ Let's not wait for a disaster to pull together. Let's gather our \ energy and purpose, "enter the circle that we may dance." Connections can \ be woven of few and fragile threads. Remember: "it's your community if you \ are willing to work for it."\ \ "We write into the storm together."\ —Lucy Adkins\ \ Cowgirl up, cupcakes, and create community wherever you are, even if you \ and your confederates are way beyond Crazy Woman Creek.\ \ Copyright © 2004 by Gaydell Collier, Nancy Curtis, and Linda M. \ Hasselstrom. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company.

Introduction : beyond Crazy Woman CreekBanana bread and coffee3The shearing4Object of affection4At the line dance cafe6Posse to the rescue7Superior laundry, Sheridan, Wyoming13Right place, wrong time14Casserole culture in highlands ranch14Patchwork for baby17Wonderbra soldiers17Picking peaches18Run toward suffering20Watch the big house burn22Room for a small house25The hippie central library fest26Rhino rump, chicken palace, and kindness29Waiting to dance30Where the river bends31Far-flung neighbors32I suppose it was the food35Bound37Soakers unite39No one baked cookies41Boomtown, babies, and strawberry pie42No treasure in Bismarck44Grab your shawls, girls!45Warm hearts, cold reality46Standing in line at Aldrich's Grocery50A light shawl on a cool night51Echoes on the wind53Cliff dwellings : Mesa Verde57Path to a small world58Simply, soul soup60After moving away from 61063Have cattle, will travel65Women of the Journal star67Valley essential : Gladys Smith69Old women's domain70Mine shack memories71Well - you told me to72Surviving at great cost73From Canton to Spearfish74The brown sofa77Feedings the spirit77At the greasy spoon78Vagina dialogues on the road trip80Shelter for each other81Champagne toast at midnight83The logging bee84Wood ash on the wind86Nevada firestorm87Women in pickups90Gifts from our hands and hearts91To dance with grace91Tupperware therapy94Banding together in San Francisco95Concert of energy97Writing into the storm101Too busy to be church ladies102How do I thank ...?105We four106A haunting experience109Rejuvenating the Clearfield Hall and me112The wolf pack in the school district113The non-musicals sing their last song116Fifty years of potluck117The woman who didn't fit in119Wednesdays at Walgreens120A couple of nights before Christmas121Why we still sing when other choirs dissolved123Savoring the circle124Perching126Hallelujah! faith circle!129Bingo babes130I'm afraid I can't attend the next meeting132Concerning my Hutterite cousins133Straightforward and unafraid137The spite and malice sewing circle139A square of winter light140Speak, throw up, or die141What it took143You always start with a baptism145The brotherhood of railroad workers146Our ladies of the farm148Convergence of horse-crazy women149Hook and turn151Cindergals never looked back152The hobo Mark swooshed155Endurance in harmony156The caring Cleveland club156A good thing to do157The circle dance159"I bring you the gift of my dying"160The Ramah farmers' market163Forecasting the future of food164Down gravel roads166Woman sculpted of stones167Making room for Jesus and Buddha168What I hate most about you171Pickin' chickens172Watch where you step173Comments from the crow's-nest176Rodeo moms177When the world split179Tuesday tea181Choir practice at the Bongo Lounge182Popcorn in the ER185Old woman with a mind186Electric Avenue books187September 12, 2001190Funeral meats191Weeders, all195The communion of saints196Desert filament201The far side of Maple Street202Quilting a dissertation206The living, the warm207The elegance of white things209Celebrating mass in a nightgown212In a time of war214Stitching my life project214I like it that way216Leaving sad town218Silent renewal222More alike than different223Ongoing sustenance224Tapestry woven of stories226Your sister's keeper229Ghost dance II229Feeling North Dakota and looking California231Things I would not miss232Stretching friendship235Alone, not lonely237Tortilla round238Slot mamas240Crone circle : grandmothers giving wisdom241United Methodist fellowship243Beadwork244Colorado ritual247Cowgirl up, cupcakes248Re-entry : homeward bound250Liesel, you're a good Christian251Sonnet for my grandchild254Never silent again255The drumbeat continues256Checkup, checkout258Plant sale grows roots261One panel of a quilt263One word at a time264Dealing Uno and life267Anaconda copper dreams268Where they know my name269La Mujer y Su Cultura272On watermelon and stout roads272A world apart273Belongings274AfterWord276Contributors279Acknowledgments297Credits298

\ Library JournalThe editors and many of the authors featured in Leaning into the Wind and Woven on the Wind have reunited for another likable collection of essays and poetry featuring women of the American West. This hodgepodge is comfortable and folksy yet diverse. Where else can a reader find an essay by a Nebraska Buddhist followed by a poem recalling "Vagina Dialogues on a Road Trip"? Themes emerge throughout the collection-how women minister to one another with food and a helping hand, how laughter heals and protects, and how vitally important relationships are to women, especially to those living in remote areas. Many selections are heartwarming, some are chilling in their truthfulness, and many demonstrate the necessary humor of survivors. Recommended for public and academic libraries with regional collections.-Jan Brue Enright, Augustana Coll. Lib., Sioux Falls, SD Copyright 2004 Reed Business Information.\ \