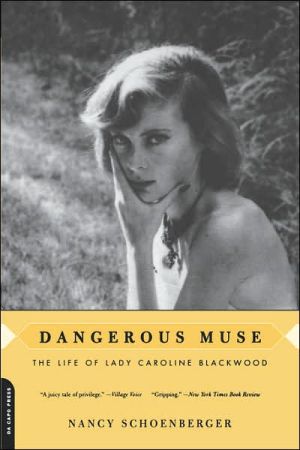

Dangerous Muse: The Life of Lady Caroline Blackwood

You can see her dark-eyed beauty in photos by Walker Evans, and her bewitching figure in paintings by Lucian Freud. She is the mermaid of whom poet Robert Lowell writes in The Dolphin (and he was clutching her portrait when he died). She was Lady Caroline Blackwood, legendarily witty and alluring but also a legendary drunk. Raised an heiress to the Guinness fortune, Blackwood (1931-1996) moved easily among the aristocracy, the bohemians of postwar England and the liberal intelligentsia of...

Search in google:

"A juicy tale of privilege...accompanied by genius, scandal, and eventual dissolution." -Village VoiceNew York Times Book Review - Hilary SpurlingDangerous Muse is not so much a literary biography as a fable for our own times -- dramatic, chilling and suggestive -- in the same way as Grimm's fairy tales (or for that matter Freud's case histories) were for theirs.

\ Hilary SpurlingDangerous Muse is not so much a literary biography as a fable for our own times -- dramatic, chilling and suggestive -- in the same way as Grimm's fairy tales (or for that matter Freud's case histories) were for theirs.\ — New York Times Book Review\ \ \ \ \ Born into title and wealth, Anglo-Irish aristocrat Caroline Blackwood (1931-1996) made use of both assets. Raised on her family's fortune, Blackwood grew up on a rambling country estate ("5,400 acres then, dwindled from its original 18,000"), played debutante in 1949 and was introduced to her first husband, painter Lucian Freud, by Ann Fleming (wife to James Bond creator Ian). In the decadent times that followed, Caroline and Lucien became the toast of 1950s London. For Blackwood, wild times, two more husbands and at least one capricious lover followed. Schoenberger suggests that the beautiful Blackwood was some kind of dark muse (dark, because her relationships were always troubled) to her three artist husbands. The book, which relies on excerpts from Blackwood's writings and a collection of quotes from those who knew her, makes for a fascinating read, yet it never quite gets beyond the sad portrait of a desperate woman with too much time on her hands.\ —Daneet Steffens \ \ (Excerpted Review)\ \ \ Library JournalLady Caroline Blackwood, who died in 1996, is best known in the United States for her turbulent marriage to poet Robert Lowell (the last of her three husbands). Born into the Anglo-Irish nobility in 1931, she was an heiress to the Guinness fortune and one of the most glamorous socialites of her day. Brilliant but moody, she first married the painter Lucian Freud, who commemorated her eerie beauty in several famous paintings. Although she had written sporadically throughout her life, it was not until after Lowell's death in 1977 that she began to concentrate on her haunting, often autobiographical fiction and nonfiction (e.g., Great Granny Webster, which was shortlisted for the Booker). Blackwood died before she and Schoenberger (creative writing, Coll. of William & Mary; Girl on a White Porch) could agree on this biography. The subsequent destruction of her papers, plus the refusal of Blackwood's children and family to contribute, has made this a rather thin study of a bewildering woman whose character is not entirely explained by hereditary eccentricity, alcoholism, and an unhappy life. For general and specialized collections. (Illustrations not seen.) Shelley Cox, Southern Illinois Univ. Lib., Carbondale Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsThe unhappy life of a jet-setting socialite and intellectual, sympathetically retold. Born in 1931 into the wealthy, influential Guinness family in Northern Ireland, Caroline Blackwood was renowned for both her beauty and her intelligence. A familiar figure among the smart sets of London, Paris, and New York, she served as confidante and muse to the likes of Cyril Connolly, Robert Silvers, Roger Bacon, Ned Rorem, and Jonathan Raban—and married (in succession) painter Lucian Freud, composer Israel Citkowitz, and poet Robert Lowell. Although Blackwood's life was ready grist for gossip columnists, Schoenberger (Long Like a River, 1998, etc.) treats her subject seriously, noting that for all its social and arty swirl, Blackwood's life came to center on her work, a body of novels and journalism that Schoenberger compares favorably to the work of such contemporaries as John McPhee and Tom Wolfe. And while Blackwood enjoyed the privileges of an aristocratic birth, the fates frowned on her nevertheless, and from very early her life was set on a sorrowful course. Her father was killed in Burma during WWII, her mother abandoned her to nannies and boarding schools, her husbands subjected her to various cruelties, infidelities, and forms of madness, one of her children died young, and reviewers never quite recognized her for the clearly talented (if minor) writer that she was. This bad luck, Schoenberger hazards, contributed to Blackwood's uncertainty over whether the world "was a godless place or one ruled by a malicious intelligence." The author does not shy away, however, from an important aspect of the story—namely, that many of Blackwood's tragedies came from her own seeminglyungovernable self-destructive tendencies (manifested most clearly in lifelong alcoholism and bouts of depression). A capable account, both critical and admiring, that may win Blackwood new readers.\ \