Darwin's Sacred Cause: Race, Slavery and the Quest for Human Origins

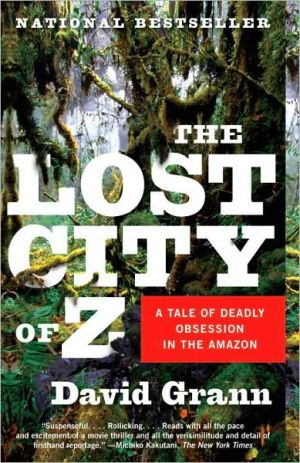

There has always been a mystery surrounding Darwin: How did this quiet, respectable gentleman come to beget one of the most radical ideas in the history of human thought? It is difficult to overstate what Darwin was risking in publishing his theory of evolution. So it must have been something very powerful—a moral fire, as Desmond and Moore put it—that helped propel him. That moral fire, they argue, was a passionate hatred of slavery.\ In opposition to the apologists for slavery who argued...

Search in google:

An astonishing new portrait of a scientific icon In this remarkable book, Adrian Desmond and James Moore restore the missing moral core of Darwin s evolutionary universe, providing a completely new account of how he came to his shattering theories about human origins. There has always been a mystery surrounding Darwin: How did this quiet, respectable gentleman, a pillar of his parish, come to embrace one of the most radical ideas in the history of human thought? It s difficult to overstate just what Darwin was risking in publishing his theory of evolution. So it must have been something very powerful a moral fire, as Desmond and Moore put it that propelled him. And that moral fire, they argue, was a passionate hatred of slavery. To make their case, they draw on a wealth of fresh manuscripts, unpublished family correspondence, notebooks, diaries, and even ships logs. They show how Darwin s abolitionism had deep roots in his mother s family and was reinforced by his voyage on the Beagle as well as by events in America from the rise of scientific racism at Harvard through the dark days of the Civil War. Leading apologists for slavery in Darwin s time argued that blacks and whites had originated as separate species, with whites created superior. Darwin abhorred such "arrogance." He believed that, far from being separate species, the races belonged to the same human family. Slavery was therefore a "sin," and abolishing it became Darwin s "sacred cause." His theory of evolution gave all the races blacks and whites, animals and plants an ancient common ancestor and freed them from creationist shackles. Evolution meant emancipation. In this rich and illuminating work, Desmond and Moore recover Darwin s lost humanitarianism. They argue that only by acknowledging Darwin s Christian abolitionist heritage can we fully understand the development of his groundbreaking ideas. Compulsively readable and utterly persuasive, Darwin s Sacred Cause will revolutionize our view of the great naturalist. The New York Times - Christopher Benfey Darwin's power, according to Desmond and Moore, lay in his marshaling an argument for the unitary origin and hence "brotherhood" of all human beings, and this, they argue, is precisely what Darwin achieved in The Origin of Species and later in The Descent of Man. The case they make is rich and intricate, involving Darwin's encounter with race-based phrenology at Edinburgh and a religiously based opposition to slavery at Cambridge.

DARWIN'S SACRED CAUSE\ RACE, SLAVERY, AND THE QUEST FOR HUMAN ORIGINS \ \ By Adrian Desmond James Moore \ THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS\ Copyright © 2009 Adrian Desmond and James Moore\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-226-14451-1 \ \ \ Chapter One\ The Intimate 'Blackamoor' \ No 'evil more monstrous has ever existed upon earth'. So said the leading anti-slavery campaigner Thomas Clarkson on celebrating the end of the slave trade. Clarkson was supported and part-financed by Charles Darwin's grandfather, the master potter Josiah Wedgwood. But the words could equally have been Darwin's – or those of his other grandfather, the libertine, poet and Enlightenment evolutionist Erasmus Darwin. For all of them slavery was a depravity to make one's 'blood boil', in Charles Darwin's words, a sin requiring expiation: 'to think that we Englishmen and our American descendants ... have been and are so guilty'. The trade – transporting snatched Africans to labour till their deaths in the fields and factories of the New World and elsewhere – was outlawed in the British dominions in 1807. That was two years before Darwin was born, and he would grow up awaiting abolition of the damnable slavery system itself in the British colonies (which came in 1833).\ Even then Charles Darwin continued to see the worst excesses of slavery for himself on the Beagle voyage (1831–6) and he was revolted by its 'heart-sickening atrocities'. Slavery, justified by the planters' belief that black slaves were a separately created animal species, was the immoral blot on his youthful landscape and a spur to his emancipist study of origins – evolution, we call it today. The enormity of the crime in the eyes of the Darwins and their Wedgwood cousins was understandable: the African slave abductions had resulted in probably the largest forced migration of humans in history.\ The mass action against slavery between the 1780s and 1830s engendered a new feeling of patriotic pride in British liberty after the loss of the American colonies. The campaign made anti-slavery 'unprecedentedly popular' in Darwin's formative years. He was not alone in growing up in such a humanitarian environment; he was not alone in sharing its goals. But Darwin's undermining of slavery was a unique scientific response and it would shape the modern world.\ Charles Darwin's family engagement with abolitionism began with his grandfathers, the doctor, philanderer, poet and prodigiously fat Erasmus Darwin on the one side, and the stern Unitarian and industrial potter Josiah Wedgwood on the other. These men would meet on full-moon-lit nights, with other prime movers who would power a technological revolution, in an informal Lunar Society of Birmingham.\ Birmingham was a proud manufacturing town, full of self-made industrialists, its iron foundries exporting goods through Liverpool docks. But some trade items were sinister. In Erasmus's day almost 200 British ships were plying the slave trade between Africa and Jamaica, more than half out of Liverpool. These ships alone transported 30,000 slaves a year. The city had grown fat on the trade in flesh and was 'so risen in opulence and importance' as to be inured to the immorality of it all. The tall ships heading back to Africa carried 'a cheap sort of fire-arms from Birmingham, Sheffield, and other places', as well as powder, bullets and iron bars, all made in the Birmingham area, and all used to barter for the slaves. The local trade was partly funding slavery. There was a growing awareness of the fact: in 1788 the ex-slave Olaudah Equiano had passed through Birmingham on a propagandist anti-slavery tour and been well received. There was plenty of call on the new industrial furnaces, with Jamaica's slaves being punished by having 'iron-collars [fastened] round their necks, connected with each other by a chain'. Erasmus Darwin was livid in 1789 on learning of the destination of these foundry products. Already planning ways to get Parliament to stop the trade, he wrote to Josiah Wedgwood: 'I have just heard that there are muzzles or gags made at Birmingham for the slaves in our islands.' One of these instruments, scarcely suitable for beasts, could be 'exhibited by a speaker in the House of Commons' during a coming debate. Or what about a specimen of the 'long whips, or wire tails', used in the West Indies? When it came to swaying a debate, 'an instrument of torture of our own manufacture would have a greater effect, I dare say'. Wedgwood canvassed the likely impact with his London friends.\ All emancipation stirred Erasmus Darwin. In the 1780s, when Quakers and then Anglicans began organizing against the trade, Erasmus lent them his devastating pen. Like everyone, he stood aghast at the Zong slave-ship atrocity, in which 133 sickly blacks were flung overboard so that the owners could claim the insurance on their lost 'property'. Fellow Lunar members were equally affected by the Africans' plight, not least Darwin's best friend and eccentric in benevolence, the Rousseauian Thomas Day (who so cared for animals that he refused to break horses). He versified in The Dying Negro on a runaway slave who chose suicide rather than be separated from his white lover. Verse best served the cause, and in mastering the art, Erasmus himself mastered his passions. He could celebrate 'the loves of the plants' in his bucolic Botanic Garden, but then out of the blue, the sunny lines flashed incandescent, a lightning rod for his wrath:\ E'en now in Afric's groves with hideous yell\ Fierce SLAVERY stalks, and slips the dogs of hell;\ From vale to vale the gathering cries rebound,\ And sable nations tremble at the sound! –\ – YE BANDS OF SENATORS! Whose suffrage sways\ Britannia's realms, whom either Ind obeys;\ Who right the injured, and reward the brave,\ Stretch your strong arm, for ye have power to save!\ ... hear this truth sublime,\ 'HE, WHO ALLOWS OPPRESSION, SHARES THE CRIME.'\ \ No Doctor Pangloss wrote those lines, or\ The whip, the sting, the spur, the fiery brand,\ And, cursed Slavery! thy iron hand ...\ \ The revelations of slave misery and brutality were such as no enlightened Europe should endure.\ And Erasmus was a child of the Enlightenment. A fervid republican, he flag-waved for the American and French revolutions. He invented machines, predicted the future and wrote poetry copiously. All progress for him was linked to an upward-sweeping, sex-driven material evolution, as set out in his vast bio-medical treatise on 'the laws of life', Zoonomia. That evolutionary vision might have been buried in the book but for Erasmus's popular poetry. Verse made the doctor's love of sex and progress a political force. 'Darwinianism', it was dubbed – to versify in the manner of Erasmus Darwin. In the long years of Tory crackdown in Britain following the French Revolution, his works were slammed as atheistic and subversive. Even young Charles Darwin at Edinburgh University in 1825–7 would read diatribes on his grandfather's 'unbounded extravagance', which 'benighted, bewildered, and confounded' readers with its near blasphemous idolatry of the material world. And it would provide a salutary tale, reminding the grandson of the need for circumspection.\ Old Erasmus loathed cruelty, whether to man or beast. All creatures in his evolving world were sensitive, suffering and deserving of respect, even the humblest. Never holier-than-thou, he delighted in being lowlier-than-thou. Zoonomia trumped the Bible's 'Go to the ant, thou sluggard' with 'Go, proud reasoner, and call the worms thy sister!' With mind reaching so low in the scale of nature and morality held so high in this vaunted 'age of reason', nothing would keep Erasmus from fighting against cruelty to any beast, or any human with skin-deep difference. To achieve the greatest health and happiness there should be 'no slavery ... no despotism'. In his botanical Phytologia, on the subject of West Indies' sugar cane, he burst out, 'Great God of Justice! grant that it may soon be cultivated only by the hands of freedom, and may thence give happiness to the labourer, as well as to the merchant and consumer.'\ His fellow members of the Lunar Society concurred. Skilled 'mechanicks' and 'chymists', manufacturers and doctors, poets, even the radical Unitarian minister Joseph Priestley: the Lunaticks some called them, and they were indeed mad about science, with nine of the twelve being elected Fellows of the Royal Society. Iron, coal and steam were elemental to them, fly-wheel revolutions as vital as political revolutions. Their beam engines and great factories seemed to be driving forward the progress that Erasmus saw running up through nature, with no end in sight. Science-based enterprise would elevate and emancipate humanity as surely as good men acting together would stamp out the barbaric slave trade.\ Most were strong Dissenters (they stood outside the state-established Church of England and suffered discrimination as a result – thus many were political and moral reformers). The Lunaticks held a progressive, unconventional faith like Erasmus's. One was his patient Josiah Wedgwood I, Charles Darwin's maternal grandfather, renowned for his fashionable tableware and vases. Prosperity was no hedge against mortality for the master potter – ailments plagued the Wedgwood family. Josiah's smallpox-affected right leg was amputated below the knee, a terrifying ordeal without anaesthetic. Josiah insisted on watching the operation. Afterwards the anniversary became 'St Amputation Day', but he endured shooting pains for the rest of his life from a phantom limb and ill-fitting wooden prostheses.10 Josiah and Erasmus both knew suffering.\ In his potting sheds at 'Etruria' in Staffordshire, Wedgwood sought to make 'such machines of the men as cannot err', and a timepiece ran the shifts clockwork fashion. His religious universe ran in a similar way. The family were 'rational Dissenters', discarding the Trinity and Jesus's divinity as corruptions of early Christianity. In their creedless Unitarianism – taught rigorously by Wedgwood's factory chemist Priestley – God's world was like a self-perfecting engine, with each person improved by following the perfect man, Jesus. Salvation was open to all, without regard for rank, ritual or race. Women found the levelling ethos empowering, and the next generation of Wedgwood wives and daughters would contribute more than their equal share to the anti-slavery cause.\ Such radicals did not fare well in the rumour-ridden aftermath of the French Revolution. In July 1791 Priestley's chapel, house and laboratory were gutted by a reactionary mob crying, 'No philosophers – Church and King for ever!' Other Lunar men, terrorized, armed themselves and their factories. Darwin and Wedgwood became more circumspect after Priestley fled to America. The next generation made its peace with the Church, baptizing their children (thus Charles Darwin was christened an Anglican). A Wedgwood grandson even became the family's vicar and young Charles Darwin, after failing at medicine, would be sent to Cambridge University to prepare for ordination.\ Josiah and Erasmus had teamed up to fight the slave trade, the corpulent doctor with his sharpened pen, poised like a spiky buttress beside the peg-leg potter, whose flair for merchandising and London showroom gave him metropolitan connections. Parliamentary petitions against the slave trade had sprung up in 1788, over a hundred of them countrywide, the people's voice in an age when few had the vote. Erasmus sent Josiah's on to the Lunatick 'Birmingham F.R.S.s' for their signatures and forwarded it on for more to 'Dr Darwin of Shrewsbury', Erasmus's son Robert, Charles Darwin's father. But the sugar merchants and planters' lobby was powerful, and Parliament only agreed to regulate conditions on the slave ships. Even so, as William Wilberforce, the leading parliamentary spokesman for abolition, prepared to open the first debate in the House of Commons, a shocking broadsheet appeared on the streets. It showed the section of a loaded slaver with 482 black bodies packed below decks, the legal limit being an appalling 454. All parties redoubled their efforts to counter this black agony brought on by white greed.\ The anti-slavery side of manufacturing fought back. In London, the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, founded in 1787, needed an official seal. Wedgwood, one of the first on its Committee, produced the image: a black man on one knee, shackled hand and foot, with eyes and hands pointing heavenward, pleading 'Am I not a Man and a Brother?' The words might have been his but the kneeling figure resonated as a piece of Christian art. A seal and woodcut were made, and Etruria cast a small oval medallion, with the slave shown in relief, 'in his own native colour'. It stood out in the pottery's range of collectable cameos. But it was not for sale. Wedgwood produced thousands at his own expense for distribution by the Society and its friends. In 1789 Benjamin Franklin, president of Philadelphia's abolition society, was sent a consignment. Batches were continually fired to keep pace with parliamentary debates, and inevitably the tiny ovals became a must-have solidarity accessory, a sort of poppy or yellow ribbon of its day. Gentlemen mounted it on snuff-boxes, women in hair-pins, bracelets and pendants. Commercial variants came out, with coat-buttons, shirt-pins, medals and even mugs showing, sometimes ignominiously, 'the poor fetter'd SLAVE on bended knee / From Britain's sons imploring to be free'.\ Darwin printed those lines beside a woodcut in his Botanic Garden, with a note explaining the cameo was 'of Mr. Wedgwood's manufacture'. He had 'distributed many hundreds, to excite the humane to attend to and to assist in the abolition of the detestable traffic in human creatures'. Darwin continued, imploring:\ Hear, oh, BRITANNIA! potent Queen of isles,\ On whom fair Art, and meek Religion smiles,\ Now AFRIC'S coasts thy craftier sons invade,\ And Theft and Murder take the garb of Trade!\ – The SLAVE, in chains, on supplicating knee,\ Spreads his wide arms, and lifts his eyes to Thee;\ With hunger pale, with wounds and toil oppress'd,\ 'ARE WE NOT BRETHREN?' sorrow choaks the rest;\ – AIR! Bear to heaven upon thy azure flood\ Their innocent cries! – earth! Cover not their blood!\ \ In London, Josiah shared his business skills with the Committee. At home he distributed tracts and held 'country meetings' to rouse the gentry. Were they to know a 'hundredth part of what has come to my knowledge of the accumulated distress brought upon millions of our fellow creatures by this inhuman traffic', they would rise up in protest. He helped former slaves, notably Olaudah Equiano. An Igbo, kidnapped in Nigeria as a child, Equiano had endured every trial and was now tramping the country, proselytizing and publicizing his autobiography. Bristol lay on his itinerary, but it was a dangerous slave-sugar port, and he turned to Josiah for help. He feared being press-ganged 'on the account of my Publick spirit to put an end to the accursed practice of slavery' and ending up back in chains. Josiah stood ready to have his London business manager intercede with the Admiralty, should the need arise.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from DARWIN'S SACRED CAUSE by Adrian Desmond James Moore Copyright © 2009 by Adrian Desmond and James Moore. Excerpted by permission of THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

IllustrationsIntroduction Unshackling Creation1 The Intimate 'Blackamoor' 12 Racial Numb-Skulls 273 All Nations of One Blood 494 Living in Slave Countries 685 Common Descent: From the Father of Man to the Father of All Mammals 1116 Hybridizing Humans 1427 This Odious Deadly Subject 1728 Domestic Animals and Domestic Institutions 1999 Oh for Shame Agassiz! 22810 The Contamination of Negro Blood 26711 The Secret Science Drifts from Its Sacred Cause 29712 Cannibals and the Confederacy in London 31713 The Descent of the Races 348Notes 377Bibliography 422Index 457

\ Thomas HaydenIn lesser hands, this recasting of Darwin's life as an extended anti-slavery campaign could seem like a stretch, perhaps to justify a book for the Darwin-Lincoln double anniversary. But Desmond and Moore, professional historians of science who are widely regarded as Darwin's finest biographers, barely mention Lincoln (though they do show Darwin reading the news of America's Civil War with great interest). More to the point, the authors follow Darwin's example by deciding that the best way to prove a controversial point is "to pile on crippling quantities of detail." Drawing on his manuscripts, notebooks, letters and even marginal jottings in books, they construct a theory of both broad scope and meticulous documentation, leaving critics with few holes to probe.\ —The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Christopher BenfeyDarwin's power, according to Desmond and Moore, lay in his marshaling an argument for the unitary origin and hence "brotherhood" of all human beings, and this, they argue, is precisely what Darwin achieved in The Origin of Species and later in The Descent of Man. The case they make is rich and intricate, involving Darwin's encounter with race-based phrenology at Edinburgh and a religiously based opposition to slavery at Cambridge.\ —The New York Times\ \ \ Publishers WeeklyWho better than Desmond and Moore, Darwin's acclaimed biographers, to bring a fresh perspective to Darwin's central beliefs? "No one," they say, "has appreciated the source of that moral fire that fuelled his strange, out-of-character obsession with human origins." This masterful book produces a perspective on Darwin as not only scientist but moralist. Darwin's deep abolitionist roots, say the authors, led him to ask the questions he did. Homing in on Darwin's moral and intellectual formation, and drawing on notebook jottings and marginalia, Desmond and Moore argue persuasively that the centerpiece of Darwin's work was demonstrating the "common descent" of all human races, using science rather than activism to subvert the multiple origins view promoted by slavery's advocates. His humanitarian approach to science, the authors say, makes him more of a moral agent than his critics would concede, while the moral drive behind his science goes against today's ideal of disinterested scientific objectivity. Desmond and Moore build a new context in which to view Darwin that is utterly convincing and certain to influence scholars for generations to come. In time for Darwin's bicentennial, this is the rare book that mines old ground and finds new treasure. (Jan. 28)\ Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalPerhaps because he left behind such an extensive chronicle of his own writings, Darwin, the man, has inspired abundant literature aiming to understand the workings of his mind, his personal passions, and his inner demons; for example, the authors' The Life of a Tormented Evolutionist. In a similar vein, their newest book reinterprets much of his life work as having been motivated by an altruistic humanitarian vision and an equally intense abhorrence of slavery. Drawing from a wealth of documentary sources from the era, they explore how the Enlightenment's scientific objectivity coexisted with colonial racism and how Darwin uniquely honed his science according to a set of values that he hoped could provide a transcendent vision of a "great human family," as presented in The Descent of Man. Well researched, likely to be controversial (some will call it revisionist history), this book provides another enlightening glimpse into a life of seemingly infinite complexity.\ \ —Gregg Sapp\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsCo-authors of the massive Darwin (1992) offer a new take on the impetus for his theory of evolution: It was "moral passion," rather than the force of observed, recorded and analyzed facts, that fired his work. Darwin grew up in an abolitionist culture, Desmond and Moore demonstrate. Both of his grandfathers, Josiah Wedgwood and Erasmus Darwin, were ardent supporters of the antislavery movement, and his older sisters firmly instilled its message in him. Add to this the impact of his teenage apprenticeship in taxidermy to a freed slave, "a very pleasant and intelligent man," and his shocking encounters with the brutality of human bondage during his years on board the Beagle. Drawing heavily on unpublished correspondence and Darwin's notes about and early drafts of On the Origin of Species, the authors argue that it was abhorrence of slavery that led this country gentleman to risk his reputation in a conservative society by linking all races to a common, more primitive ancestor. They show Darwin working out his theory of sexual selection as the means by which human races became differentiated. In recounting the development of his theories, and his reservations about presenting them and exposing himself to society's wrath, the authors supplement the history of science with the history of slavery and racism in the 19th century. They cite and quote from the work of James Cowles Prichard, John Bachman, Sir Charles Lyell, Asa Gray and Louis Agassiz, among others. Modern readers may be startled by Victorians' openly racist language and the general assumption-among men of science as well as religious figures and political leaders-that whites, especially Englishmen, were superior. Championingthe abolition of slavery did not mean accepting blacks as intellectual or cultural equals, and Darwin was apparently no exception to this general rule. Stimulating, in-depth picture of 19th-century scientific thinking and racial attitudes.\ \