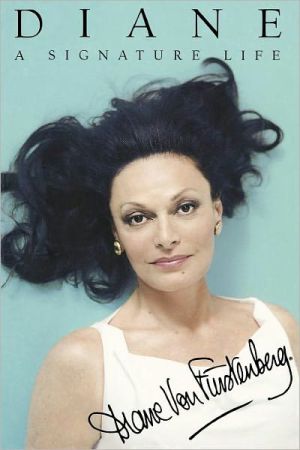

Diane: A Signature Life

Diane is the frank and compelling story of an extraordinary woman and her adventures in fashion, business, and life. "Most fairy tales end with the girl marrying the prince. That's where mine began," says Diane Von Furstenberg.\ She didn't have to work, but she did. She lived the American Dream before she was thirty, building a multimillion-dollar fashion empire while raising two children and living life in the fast lane.\ Von Furstenberg's wrap dress, a cultural phenomenon in the seventies,...

Search in google:

Now available again in a slightly updated version for the '90s, Diane Von Furstenberg's wrap dress, a cultural phenomenon that hangs in the Smithsonian Institution, has sold more than five million since it was introduced in the 1970s. In Diane: A Signature Life, she looks back at a groundbreaking career that shows no sign of slowing down.New York Times Book Review - Michele Orecklin. . .[B]reezy reading for anyone who enjoys columns with a plentitutde of bold-faced names.

Chapter One \ HOW NOT\ TO START\ A BUSINESS\ No one took me seriously at first, and I can't blame them. There I was in Ronnie Ruskin's top-floor office at Best & Co., and the president of the prestigious Fifth Avenue store was looking at a very pregnant girl stuffed into a Pucci dress and showing him little jersey dresses out of a big Vuitton suitcase. I can't remember whether he liked the dresses. What I remember is going back downstairs and bursting into tears on the street.\ It was rush hour, I couldn't get a taxi, and the suitcase felt as heavy as a steamer trunk. All I could think of was Mia Farrow in Rosemary's Baby when she struggled to escape, pregnant, with her suitcase. The next day I made my retail rounds in a limousine, but the struggle at Best became a metaphor for my first two years in the fashion business.\ I had no idea what I was doing. Being so young, however, I would turn ignorance to advantage. Two months after I had my son, Alexandre, in January 1970, I got an appointment with Diana Vreeland, the editor of Vogue. That I dared to show the reigning arbiter of fashion and taste my little dresses seems cheeky to me now, but she had consented to see me. As much as I was an inexperienced young girl, I was also a European princess and embraced socially by the city. The combination opened doors, even Vreeland's--if you dared knock.\ I was, of course, terrified of Mrs. Vreeland. When I'd been with Egon during my first stay in New York and had thought that maybe I could model to support myself, I had gone to see her. "Chin up--up--UP!" she commanded me before it became clear that modeling was not my path to the future. Returning to Vogue less than a year later, with my suitcase and my samples of twelve or so dresses in three styles, was even more intimidating.\ Red. I'd never seen such bright red as the lacquered walls of her office. But everything about Diana Vreeland was expansive. There were racks of clothes in her office, tables full of jewelry, pictures everywhere. On her desk was a lit Rigaud candle and its zebra box was a pencil holder. I waited nervously for her to appear, surrounded by several of her editors and assistants, all dressed in black. Her loud, distinctive laughter preceded her as she came down the hall.\ "Chin up--UP!" she greeted me in her customary commanding style. She, too, was dressed in black with a huge Kenneth Jay Lane brooch on her shoulder, her omnipresent cigarette holder in her mouth, and her nails as red as her office walls. I showed her samples of the rumpled shirtdress, the T-shirt dress, and the skirt with a wrap top and watched anxiously as she tried a few pieces on two pencil-thin girls who would become stars--the dark-haired, exotic Pat Cleveland as a model and the red-haired, cat-eyed Loulou de La Falaise as the muse for Yves Saint Laurent. "Terrific, terrific, terrific," she said to my amazement in her theatrical voice. "How clever of you." The r's were still rolling as I found myself in the corridor, folding the dresses back into the suitcase.\ It was one of Diana Vreeland's fashion editors, the dark, long-haired, beautiful assistant, Kezia Keeble Hovey, who gave me twenty minutes that would shape my life. Fashion Week is coming up in New York, she told me. List your name in the Fashion Calendar. Take a suite for a week at the Gotham Hotel on Fifth Avenue at Fifty-fifth Street, where the California fashion houses will be showing. I didn't know where the Gotham Hotel was or what the Fashion Calendar was, but I knew I wanted to be on it. "Can I use your phone?" I asked her. When I got back to our apartment that night, the reality began to set in that I was starting a business.\ Kenneth Jay Lane, the costume jewelry designer and friend of Egon's, sent me to his lawyer, Gerald Mandelbaum, who looked at me with amusement when I told him I wanted to set up a company. "And how do you want the company name to read?" he asked with a smile.\ "Diane Furstenberg," I replied.\ "Oh, do `Von Furstenberg,'" he said. "It sounds much better."\ I made my first sale at the Gotham Hotel in April 1970 to Sarah Fredericks, a little shop in New Jersey. The order was very small, but it was a beginning. I had only the twelve or so cotton knit dress samples in a few prints and a limited collection of assorted printed silk knit tent dresses Ferretti had made up for me out of leftover fabric. To show them, I had one model, Jane Forth, who was one of Andy Warhol's girls from the Factory, as his studio was known; a startlingly pale-skinned, minuscule eighteen-year-old with totally plucked eyebrows.\ I organized a small fashion show in the banquet room of the hotel to introduce the dresses and invited all of Egon's friends and contacts. I didn't have the money to hire professional models, so I called a modeling school out of the Yellow Pages and got twelve students. It was scarcely a fashion show, but I didn't know any better. So I improvised. Someone had given me a bunch of tulips, and I gave each girl a tulip to carry for the finale.\ I had no idea who the buyers were who came in and out of the suite all week long, but I was attentive to all of them, even when they were rude. One woman, Rose Wuhl, who turned out to be an important fashion guru, walked in, looked at the cotton dresses and announced, "They're junk, but they'll sell." Before I knew it, five people from Bloomingdale's appeared to place orders.\ Other buyers passed on the dresses altogether. I remember Charlott Kramer, the famous dress buyer from Saks, looking quickly at the dresses and leaving without a word. The rejection, however, would be temporary. Eighteen months later Charlott would see the exact same dresses, and this time buy them. She would become our absolutely best account, my most fervent customer, and my loyal friend.\ The fine silk knit tent dresses turned out to be a surprising success. Fred and Gale Hayman, the pioneers of Rodeo Drive in Los Angeles, and the owners of Giorgio Beverly Hills, bought the entire assortment for their California boutique. The order for sixty or so dresses seemed huge to me at the time, especially when I had to pack and ship them myself, and would prove invaluable. The tent dresses would soon appear at Hollywood parties on Ali McGraw, Candice Bergen, and Rita Hayworth and be a great help in establishing my name on the West Coast.\ Help on the East Coast came from Egon's friends. Kenny Lane urged fashion editors to come see me during Fashion Week. Bill Blass made some calls for me, mainly to the press. Obviously, he didn't think of me as a competitor. Nobody thought of me as a competitor. There were a lot of Europeans coming to New York trying to sell things, so it wasn't so odd. And besides, we were all friends.\ Egon and I were known as a "fun couple," a young, attractive European girl married to a young, attractive European aristocrat. We entertained often, and our apartment became a sort of salon for young people like ourselves who were trying to make their way in America. Whether they were in corporate training programs like Egon or making or selling things, we were all chasing the American dream.\ Elsa Peretti and Marina Schiano, two tall, extroverted Italian girls who emerged on the seventies scene as models and favorites of Diana Vreeland because, in some ways, she thought they both looked like her, were close friends. Later Elsa would become a sculptor and a successful jewelry designer for Tiffany, and Marina would work with Saint Laurent and would later become a photographer and a stylist. Jewelry designer Paloma Picasso, the daughter of the master, was around, as was the writer Fran Lebowitz, who was driving a taxicab at the time and incubating her book Metropolitan Life.\ A lot of them were members of Halston's court. Halston represented American chic and was very much at the center of things in the early 1970s. He was designing Ultrasuede dresses and tie-dyed caftans for Babe Paley and had a shop and atelier on Madison Avenue. He was a good bit older and more established, but he loved to surround himself with younger, talented people.\ Joe Eula, the artist and illustrator, was his friend and ours, as was Loulou de La Falaise. Joel Schumacher, who was doing the windows at Henri Bendel and would go on to become a screenwriter and later a major movie director in Hollywood, was part of the group, as was Berry Berenson, the photographer and Marisa's sister, who would later marry the actor Anthony Perkins. Giorgio di Sant'Angelo, a truly original designer who used a lot of jersey and stretch fabrics in his clothes and was a great inspiration to me, was also a frequent guest, as was Kenny Lane, who would later rent one of the cottages at Cloudwalk from me. We were of different ages and different backgrounds, but we shared the same attitudes.\ Andy Warhol also became a friend of sorts. I met him through Jane Forth, my first house model at the Gotham Hotel. Andy was a silent presence, a voyeur who always had a tape recorder or a camera in his hand to record rather than participate. "Oh gee, that's great," he'd say in his distinctive little voice about everything and everyone.\ He became a fixture at our parties and at every party we went to; with the five or six courtiers he always brought with him. There was Fred Hughes, the Houston dandy; Bob Colacello, the Georgetown graduate who became the editor of Interview; the handsome twins Jed and Jay Johnson; Paul Morrissey, the director of his movies; and others. Andy was a major influence and catalyst in New York life. I don't think I ever had a long or serious conversation with Andy, but we acknowledged each other and shared an interest in antique jewelry. We were both amongst the first clients of Fred Leighton, who now has the biggest collection of antique jewelry in the world at his store on Madison Avenue but who then dealt in jewelry out of the back of his shop in Greenwich Village, where he sold Mexican dresses.\ Egon liked to collect modern art, and one night Andy asked if he could take Polaroid photos of me for a silk-screen portrait. The only white wall I could find in our apartment was in the kitchen. To lend a little cachet to the setting, I held my arm over my head, which made the shots look quite odd. It would be months before I dared look at the finished portraits. I didn't think two Polaroids taken at night in the kitchen looking somewhat like a deodorant ad would be in any way flattering or glamorous. But I liked the portrait well enough. Andy gave me one, and I bought three, two of them now hang over my office desk.\ I would pose for Andy again in 1983 or '84 for a series called Beauties. He made me and everyone else in that series put white makeup on out faces. When he died in 1987, I bought everything he'd done of me from his estate, except for one of the early ones, which now hangs in the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.\ Egon and I went out a lot in the early 1970s. A lot. We went to openings, closings, previews, balls, benefits, and private parties and became staples in the society columns. Because of our visibility, Valentino, Halston, and Yves Saint Laurent gave me their clothes to wear. I had fun dressing up, I had many ballgowns, which I wore out at night, along with lots of makeup and bracelets to the elbow on both arms. It was interesting to enter the fashion world through two different doors: as a client and as a designer.\ During the height of the winter season in New York, we averaged four invitations a night, mostly from people we'd never met. I remember having dinner with Salvador Dali and his wife, the dark and petite Gala, at the St. Regis Hotel and with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor at the Waldorf Towers. The duke and duchess were very elegant and perfectly pleasant but did not impress me very much. Dali, on the other hand, fascinated me, and so did his wife and muse, Gala, who had previously been married to the great French poet Paul Eluard.\ We also traveled a lot. In between my trips to Ferretti's factory in Italy, we circulated between our house in Sardinia, Egon's mother's chalet in Cortina, and a rented house in the Pines on Fire Island next to Halston's. For one entire July, we listened to Elsa Peretti and Marina Schiano fight in Italian while Joe Eula designed scarves with Loulou de La Falaise. The great film director Luchino Visconti, who had recently made Death in Venice, with my friend Marisa, also spent a few days at our house there. I remember walking the beach together at sunset, going through the dunes, and ending with tea on the terrace of a house at Cherry Grove, pretentiously called Belvedere. It was very funny to be sitting there, watching the amused and disgusted expression on the face of one of the greatest esthetes of all time.\ Our jet-setting lifestyle made good copy for the social columnists. Women's Wear Daily, The New York Times, and the New York Post ran articles about me and my first collection during Fashion Week in 1970, though the emphasis was more on me than on the dresses. Eugenia Shepherd in her New York Post column "Inside Fashion" concentrated the first two paragraphs on the parties the "Prince and Princess Egon von Furstenberg" were invited to and didn't mention my clothes until the third paragraph. Though the dresses were essential to me, to the press the little dresses I was selling were an afterthought.\ Everybody was intrigued by this young princess who was making simple go-everywhere dresses instead of ball gowns for the elite. And it justified their stories. "In Private Life, Diane is known as Princess Egon von Furstenberg," ran the headline on the article in Women's Wear Daily that pronounced me "New York's newest designer." Bernadine Morris at The New York Times titled her story "For the Princess, a Stylish Business."\ Those first three articles were invaluable in launching my new business and added another important account to my first sales. Across the street from the Gotham Hotel was the Revlon beauty salon, where I went one day during Fashion Week to have my hair done. "Are you Diane Von Furstenberg?" asked a small blond woman under the hair dryer next to mine. When I told her yes, she introduced herself. "My name is Phyllis Davidson, and I'm a Lord & Taylor buyer," she said. "I want to come see you." She did and placed what seemed like a large order at the time for cotton T-shirt dresses and shirtdresses in a chain print. I remember the specific print well because it would be on a personal appearance for the launch of these dresses with Phyllis at the Lord & Taylor in Hartford that I would discover Connecticut for the first time. It was October, and the colors of the fall foliage were so extraordinary that I decided that Connecticut was where I would like to have a home.\ The first publicity certainly helped to get orders from the stores for two hundred or so dresses. Perhaps some of the naivete and spontaneity of my first fashion show was attractive to the fashion editors. Filling the orders, however, was a nightmare, especially after the demand grew when Diana Vreeland ran one of the dresses in Vogue soon after I'd seen her in the spring of 1970.\ I had no office, no staff. I stored the dresses in the dining room of our apartment and processed the orders with office supplies I bought at Woolworth. Because the orders were relatively small, I had to fly to Italy once a month to beg Ferretti to fill them. His printing, knitting, and sewing factories were designed to make T-shirts in mass production. He couldn't stop his machines to cut such small quantities, let alone make special prints. I had to beg, cry, and use every ounce of charm. "Stick with me," I pleaded. "I promise you will be rewarded." Finally he would do the clothes as a personal favor and a sign of faith rather than as a professional investment.\ The shipments from Italy were often late and sometimes wrong, leaving me in some disfavor with store buyers who had ordered them. They did not complain, though, because the clothes sold quickly anyway. I spent what seemed like years in the customs warehouses at Kennedy Airport breaking down the bulk shipments for reshipment to individual stores. The first shipment, in the winter of 1970, was the worst. The fabric content of each item was written in Italian, and for hours I sat in tears on the floor in the freezing cold warehouse of Air India in front of the open boxes, crossing out all the labels in Italian and rewriting them in English. I couldn't have been farther from the glamorous princess life being written about in the newspapers.\ I was also pregnant again, just three months after giving birth to Alexandre. He had been delivered by emergency cesarean section on January 25, 1970, after I had been in labor for sixteen hours. Tatiana was due in February 1971, and the doctor advised me to have another cesarean, this one planned, because I had hardly healed from the last. He gave me a two-week window, and I chose February 16. Two and five added up to seven as did one and six, which I took to be a good omen. And it was. Tatiana was as healthy and beautiful as her brother, making me a very happy and proud mother of two at the age of twenty-four. I was so young, I hadn't even had the time to wish for children before they were already there. I had not thought I would be very maternal and yet their births changed my life. They became my center, gave new sense to my existence, and forced me to be aware and responsible forever.\ I was back in the warehouse a week after Tatiana was born to sort and ship the spring orders. We had a nanny to help look after the children when they were very young. To house everyone comfortably, including my mother, who spent eight months a year with us, we bought the apartment adjoining ours in our building on Park Avenue and broke through the wall. I spent every minute I could with the children, whom I loved with a passion more powerful than anything I had ever felt before. I also loved my work and realized how important it was going to be for me and them.\ I felt a tremendous urgency. I was afraid that one night I was just going to stop living and never have time to tell my small children everything I had to tell them. I was also worried that I wouldn't have the time to achieve the independence that was still considered a luxury for many women in the 1970s, but was increasingly important to my identity.\ Though Egon was perfectly able and willing to support me, I wanted very much to be financially independent. Nothing makes me more miserable than to have to ask for money. At one point, when I couldn't cover my invoices at Ferretti's factory, I pawned a diamond ring that Egon and my father had given me when Tatiana was born. I was able to buy the ring back two weeks later, paying huge interest, but it meant that much to me to go about my business without any outside help.\ I had no focus groups, no marketing surveys, no plan. All I had was an instinct that women wanted a fashion option besides hippie clothes, bell-bottoms, and stiff pantsuits that hid their femininity. Though the unisex look was hot in the seventies, I was sure there was a need for simple little sexy dresses that made women feel like women. And the dresses made sense. They were sexy and practical, washable and wrinkle proof. The prints were colorful and lighthearted, the fabric soft and supple.\ The fabric was the most important. When women tried on the dresses, it was the feel of the cotton-and-rayon blend that really sold them. So did the look. What made the dresses special was that they looked like nothing on hangers but were so flattering on. You wore the clothes, the clothes didn't wear you--which was rare at the time.\ The democratization of fashion was just beginning in the 1970s. The very privileged could go to the fashion shows in Paris twice a year to see and buy very expensive made-to-order designer clothes at the couture houses such as Dior, Saint Laurent, Balmain, Givenchy, and Lanvin. Dressmakers from all over Europe would also attend the fashion shows, as would selected journalists. The most influential by far were John Fairchild, the chairman of Women's Wear Daily, and Diana Vreeland at Vogue, who between the two of them determined what styles, colors, and hemlines America--and the world--would wear that season. Everyone lived by their pronouncements. The dressmakers would buy one or two patterns at the collections that they then reproduced for their customers in their various cities in the designer fabric they had bought from the fabric manufacturers. That brought the price down somewhat in Europe, but the real deal was in America.\ Buyers for two inexpensive American stores, Ohrbach's and Alexander's, also came to the fashion shows in Paris. They too would buy some of the designer patterns, but they would then have them executed by some Seventh Avenue manufacturer and sell them very cheaply. It was the hot thing in Europe to come to New York when these clothes were available. There was a lot of excitement on the third floor of Ohrbach's when the limited number of early copies made in the original fabrics would appear. It was thrilling to buy an authentic Saint Laurent dress for only $150, and Egon and I shopped there all the time.\ The true revolution in fashion began when avant-garde Saint Laurent became the first designer to present his own line of pret-a-porter, or ready-to-wear, clothes. His line and the boutique he created to sell them in on the Left Bank in Paris were called Saint Laurent Rive Gauche and were the beginning of designer ready-to-wear in Europe.\ Designers such as Kenzo, the Paris-based Japanese designer, and the French designer Andre Courreges also offered their own ready-to-wear lines. Kenzo's clothes were colorful with ethnic inspirations, while Courreges's tended to be stiff and tailored. If you put his signature pastel, white-rimmed A-line dresses on the floor, they would stand by themselves. Personally, I still loved to wear the hippie clothes designed by the English designer Ossie Clark and by Jean Bouquin, the sexy French designer of nightclub clothes and friend of Brigitte Bardot, with their poetic look of big, ruffled shirts, crushed-velvet pants, and big clunky jewelry. But the hippie "make love, not war" look was not easy to translate into daily life for women who went to work and had children.\ Though I didn't realize it at the time, perhaps the little dresses I was designing were a bridge between the radical side of me, which wore the shortest, tiniest hot pants, a printed Saint Laurent Rive Gauche blazer, and the highest platform shoes at night, and the more conservative side, which wore little dresses during the day. My life, after all, was quite proper. I was living on Park Avenue. I had a husband who went to Wall Street every morning wearing a suit and tie, two small children, and a nanny, and in the evening I went out to cocktail parties. Though I may have been more bohemian in my heart, I related to the other mothers I saw every day picking up their children at nursery school and play groups. No one was making a proper little dress for them. So I would.\ I was up to thirty accounts by 1972, just two years after I had shown my first collection. I was still doing everything myself: designing the prints, showing the clothes, taking the orders, handling the invoices, sorting out the shipments in the warehouse at JFK, and packing and reshipping the clothes.\ I was in Brazil for carnival when I came to the conclusion that I couldn't go on working in this amateurish way. Either I had to get serious or stop. Egon and I had just been photographed by the famous photographer Francesco Scavullo for the cover of Town & Country, but the emphasis on me was still as part of a social couple and not as a designer. I didn't like that. When I returned to New York, I decided to get more serious about my work, to make a real business out of it.\ The next natural step was to become a division of some large Seventh Avenue company. That way the company could handle the distribution and the business details while I could concentrate on the designing and making of the clothes. But of the three companies I went to, none, it turned out, shared my vision.\ The president of Jonathan Logan looked at the samples I was still lugging around in a suitcase and put me in touch with the manager of one of his divisions. "These are little boutiquey clothes. This is not volume," the manager scoffed, showing me the horrible polyester dresses they made. I got a similar brush-off at David Crystal, another Seventh Avenue company.\ Only Johnny Pomerantz, the son of the owner of Leslie Fay, a large, successful Seventh Avenue company, showed interest. Perhaps it was because he was a young man and I was a young woman in my unbuttoned little shirtdress showing off my legs. Or perhaps it was because I had a copy of Larry Collins and Dominique La Pierre's O Jerusalem! with me, which, for some reason, surprised him. But it was Johnny who proved my mother's credo that what seemed like the worst thing to happen to you could be the best. No, he said, the dresses were not for his company. But yes, he would help me.\ In what proved to be the most significant advice I would ever receive, Johnny Pomerantz urged me to go into business for myself. "I think you do have a good product, even though it's not for us," he told me. "But you don't need us. You don't need anybody. Take a showroom on Seventh Avenue, hire a salesman, and just do it."\ I panicked. I was twenty-five years old in a strange country with no experience whatsoever. A showroom meant signing a lease. Seventh Avenue could mean dealing with the unions. Though you don't in fact deal with the unions when you import, I had heard stories about them. "How do I do that?" I asked Johnny. "I don't know any salesmen."\ "I do," he said.\ Within days I was negotiating with Dick Conrad, a thirty-nine-year-old entrepreneur who was looking for a new business to ran. I had very little money to offer him, but he was willing to gamble. "Give me three hundred dollars a week and twenty-five percent of the company, and I'll do it with you," he said.\ In April 1972, I reorganized my company. My partnership with Dick Conrad started with only $1,000, with $250 coming from Dick. But we were officially in business.\ We took a showroom at 530 Seventh Avenue, and I painted the walls brown, bought tables and desks from the Door Store, and hung Andy Warhol flower posters on the walls. Ferretti helped out by giving me a long line of credit. I would pay him in ninety-day cycles, while I would get paid in sixty days. So that Dick would understand what he was selling, I had a few shirts made for him out of Ferretti's fabric.\ The first months were a scramble, but we got through them. The volume of orders grew by the week, and by the end of 1972, the business had grown to wholesale revenues totaling $1.2 million. A year later, the business had multiplied sevenfold. And all because of one little dress: the Wrap.\ Probably until I die, women will tell me, "Oh, when I got married" or "When I got divorced" or "When I fell in love" or "When I got promoted I wore one of your wrap dresses." For some reason, this dress would become an icon for many women in the 1970s and a cultural phenomenon. Suburban housewives and New York lawyers bought and wore the wrap. So did actresses such as Candice Bergen, Cybill Shepherd, and Mary Tyler Moore; political wives such as Betty Ford; activists such as Angela Davis; feminists such as Gloria Steinem; models such as Cheryl Tiegs. The wrap dress transcended generations, geographical distinctions, social and economic differences. I couldn't believe it.\ The idea for the wrap dress had not come out of a strategy session or a market analysis. I had gotten the idea by watching Julie Nixon Eisenhower on television wearing a wrap top and skirt of mine she had ordered from the Lord & Taylor catalog. Why not combine the two pieces into one? I thought.\ Ferretti, as usual, was difficult. Though the volume of orders was multiplying by the week, he complained that the orders weren't enough to justify reconfiguring his machines. On the one hand, he was very supportive, but on the other, he pressured me to increase the orders. When I asked him to add the new wrap style, once again I had to beg, cajole, promise, and plead with him as well as with his factory workers, who had to put in extra time. I brought them press clips and articles to make them feel proud of the product they were working on and ate countless pasta lunches with them in the factories. Thank God I spoke Italian and could therefore talk directly to the supervisors, the ironers, the pattern makers, the sewers--everyone in the factory. By establishing a dialogue and a personal relationship with the workers, I became part of the factory. As a result, everyone did more for me.\ The first wrap dress arrived in 1973 in a wood-grain print. The dress was nothing, really--just a few yards of fabric with two sleeves and a wide wrap sash. But the V-neck wrap design fit a woman's body like no other dress: snug around the chest and arms, tied flatteringly slim around the waist, full enough over the legs for a woman to take an unrestricted stride, yet tight enough to show off her bottom. Dressed up with jewelry and high heels, the dress was ready to wear to a serious lunch or dinner; dressed down with a camisole and a lower heel, it was comfortable to wear in an office. But mostly, the wrap was sexy in the way many women wanted to feel: chic, practical, and seductive.\ In the years since, all sorts of social significance has been read into the dress. To some, the wrap became a manifesto for the liberated woman of the 1970s. The dress fit in with the woman's revolution by allowing the millions of women going off to work to be well dressed and out the door in a minute without worrying about wrinkles, buttons, zippers, hooks and eyes. The wrap also fit in with the sexual revolution; a woman who chose to could be out of it in less than a minute.\ The dress spread across a wide spectrum in the 1970s and represented many things to many different women. The wrap was featured in The Official Preppy Handbook and in Richard Reeves's 1977 book, Convention, about the 1976 Democratic National Convention. It will probably be on my tombstone: "Here Lies the Woman Who Designed the Wrap Dress."\ I was flattered that the wrap generated such attention, though I preferred the shirtdress and rarely wore the wrap myself. I had no idea that one day it would hang in the Smithsonian Institution. I just thought it was a good dress.\ In 1972, I ran my first ad in Women's Wear Daily to announce the opening of our showroom. I didn't have an advertising agency, a model, or a fancy photographer. I asked a friend of mine to take a picture of me sitting on a white cube, wearing one of my printed shirtdresses. Looking at the photograph, I picked up a pen and wrote on the cube in my own handwriting: "Feel like a woman, wear a dress! Diane Von Furstenberg." That handwritten copy line and my signature in the first ad I created would appear on every dress tag for the next decade and become my registered trademark. I had inadvertently turned my signature into a brand.\ Bloomingdale's followed my ad with its own ad for my dresses, but there was a last-minute mix-up with the model and the buyer said, "Well, let's just use Diane." I didn't know if any other designers had ever appeared in their own ads, but it seemed a natural solution at the time. From that moment on, however, the stores would identify me and the product so closely that they would insist on featuring me in every ad, whether an illustration or a photograph. The result would be a total identity of me, the product, and the brand.\ I have always understood this symbiosis and agreed with it, but the execution was really difficult. The hardest part of my work has always been to be photographed, to be totally out in front. Even now stores insist on using my image, which is hard for me when I think I look terrible. But the truth is that even when I posed for ads twenty-five years ago, I thought I looked bad.\ The American press was building my self-image somewhat, though the descriptions of me made me laugh. One newspaper described me as an "exotic beauty," which I found rather exciting. In the cover story Town & Country ran of Egon and me in March 1972, Egon was described as "blond, tall, with cherubic boyish features" and I was depicted as "dark, small, with the sultriness of a biblical temptress." I don't know how insecure biblical temptresses were, but I was still spending an inordinate amount of time and money having my hair blown and straightened.\ Strangely, what I found rewarding was going on the road to make personal appearances. The department stores made great use of my title--"The Princess Von Furstenberg is holding court in our NY Sutton Place department tomorrow" ran one early Bloomingdale's ad--and there is no question that the title added glitz to the appearances. Everybody wanted to invite me to their stores. More important to me was that I was meeting the women who were buying my clothes and getting to know America.\ Between 1973 and 1976, I traveled constantly to promote the clothes at department stores. The dresses were very light, so everything went into such a tiny little bag that I didn't have to check it. To pass the time on the planes, I stared at the map of the United States and memorized the states. I can still list alphabetically every state and every state capital in the country. On one tour, I did fourteen cities in thirteen days.\ The children were used to seeing me coming and going, and though we spent every weekend together, I missed them terribly. I often took very early flights from New York instead of traveling more leisurely the night before so I could spend the evening with the children. As often as I could, I tried to fly back to New York in time for their supper. But the lessons I was learning on my travels were invaluable.\ The American retail world was very different from that of Europe. In Europe we had only boutiques, but because of the larger scale of the cities in America, the numbers of people, and the generous amount of space, there were department stores. Every major town in America had two or three big department stores that had started as little mom-and-pop stores, then grown.\ When I first started to travel in the 1970s, I saw those stores as they had been for the last twenty years. The families who owned them were very involved in their communities. They would organize and sponsor events for the communities and often referred to their customers as "patrons." In turn, the people in the communities would work for the stores, buy from the stores, have charge accounts at the stores. The focus was all very local.\ The exodus of customers to the suburbs from the city and town centers escalated in the 1970s and started to change the whole retail complexion. The main stores downtown would open one branch in the suburbs, and little by little, as their suburban stores became more profitable, they would open another and another. It was the beginning of the mall. Gradually the downtown areas where the department stores were located began to disintegrate. The weakest of the downtown stores would fall to the strongest, and then they all would vanish. I watched it happen.\ But when I first went to those stores, the old-fashioned ways were still in place. I was a rarity, if not a novelty, to the store owners and was treated like a guest of the family. At Stix, Baer and Fuller in St. Louis, for example, I would arrive and be greeted by Mr. Baer. At the end of the day, Mr. Baer would take me to dinner with Mrs. Baer. If I didn't have friends to see or stay with, I would then go to a hotel and, depending on my mood, feel either like lonely Willy Loman on the road or like Eloise at the Plaza having a picnic on my bed.\ In cities where I did have friends, the end of the day could be confusing. While I'd been a salesperson working with the customers all day, by night I became a different person. The contrast was particularly extreme during a personal appearance at a mom-and-pop store in Flint, Michigan. In the middle of the day, the store owner asked me kindly if I had accommodations for the night. When I assured him that I did, that I was staying with friends, he insisted on driving me there. He was a little nonplussed when I directed him to Grosse Pointe, an elite suburb, but when we arrived at the gates of what promised to be an enormous house and I told him I was staying with Henry Ford II and his wife, Christina, he almost had a heart attack.\ The evening with the Fords was, in fact, quite odd. I had brought an orange angora caftan for Christina, one of just a few Ferretti had made for me out of extra fabric. During dinner in the coral-colored library, Henry announced that it looked comfortable and put it on. He wore that caftan for the rest of the evening and told me so many times that I should make men's clothes that I got a pounding headache and wished I were staying in a quiet hotel.\ In city after city, I would arrive before the stores opened, go in through the staff entrance, and meet the salespeople who would be selling the dresses. By the time the customers arrived for my personal appearance, I would have already shown the entire collection to the sales staff, the different prints, and the groupings of colors for the best display. I would also have been on whatever early-morning local television shows there were and given interviews to the local press. There was tremendous curiosity about this jet-set princess from New York who worked for a living.\ From the beginning, almost every reporter asked the same two questions: "Who is your competition?" and "What woman are you designing for?" My answers are almost the same now as they were then. I was not competing with any other designer. No one else was doing what I was. Designer clothes were expensive; mine were not. There was no name designer at that price level, though it would have been a clever move for any designer to make. But nobody did.\ My clothes were flattering to women and not overwhelming. Many designers were men, whose clothes may have shown their creativity but were not always designed to enhance a woman. It was and is so much more important for a woman to be able to express herself rather than expressing a designer's ego.\ I have always believed that a woman's clothes should feel like her, be a part of her, and an extension of her personality. That is what I have always liked for myself, and what I liked for myself, I wanted to make for others.\ As to the ongoing question about the woman I was designing for, the answer has always been simple: every woman. Taste is ageless. Flirtation and seduction are ageless. Feeling attractive and confident are ageless--and so are women's insecurities.\ I talked to women, advised women, listened to women during my tours around the country. Whether in Texas, Georgia, Illinois, or Kansas, we women spoke a common language. "Try this red print or this green print," I urged those who usually wore only brown or navy blue. "I know that's right." I walked through the display racks, helped women with their selections, then often followed them into the changing rooms. "You have to pull the wrap tight in the front so the V neck sits smoothly," I told them. Often I did the pulling myself so the women could see the proper effect. I have thousands of memories of myself looking into changing room mirrors over women's shoulders.\ I felt very connected to these women and enjoyed making them look and feel good. Nothing gave me greater pleasure than seeing a woman transformed by the way she looked in one of my dresses. The mirrors in the dressing rooms were too close, and I encouraged women to look at themselves outside on the sales floor. It was wonderful to see the surprise on their faces and the way their body language changed as they looked at themselves in the mirror. I don't think I know any other designer who actually enjoyed going into the stores the way I did then and do now again. The shyer the customer, the better; the harder the customer, the better. I loved the transformation.\ Some buyers were surprised by my instant rapport with their customers, but I took it personally when women passed judgment on the clothes without trying them on. I was so confident about the result that I often chased after women who said they were too old and too fat to wear my dresses. Reluctantly, they would agree to try one on and then would surprise themselves by buying it. This happened all over the country. Women often bought two or three dresses in different prints, then came back and bought more. By the beginning of 1973, the number of my accounts had gone from thirty stores to three hundred.\ My business relationship with Ferretti smoothed out quite a bit. I still went to Italy a lot, but the volume of dress orders was enough that he began to focus his factories on making my clothes. My relationship with Egon, however, was not as smooth. We went out too much, everything was a public event. The more I read about "the couple," the more I needed to have an identity of my own.\ On the surface, we continued to live a glamorous and often interesting life between America and Europe. At an elegant dinner in my honor in Houston, I was seated next to astronaut Alan Shepard, the first American in space and one of the few to walk on the moon. I was very impressed to meet someone who had actually seen our planet as a little ball and questioned him endlessly about it. On one of our European trips in the early 1970s, we went to the big ball with a Proust theme in Paris that Marie Helene de Rothschild hosted as a farewell to the magnificent Chateau de Ferrieres before she closed it. It was an extraordinary sight. The castle was beautifully lit inside and out, and people had made a big effort to dress up. Oscar de la Renta made me a black taffeta dress for the grand occasion, which was photographed by Cecil Beaton. The evening was a true homage to another century, a world that would no longer exist. Another trip took us to Egypt, where in Luxor I felt like Justine discovering the Karnak Temple by moonlight and bought a diaphanous silver antique caftan that I wore to Valentino's couture show in Rome a week later. All was wonderful but there were too many people around us and I felt less and less complicity with my husband.\ We also continued to entertain a lot in New York, and our apartment became even more of a mecca for visiting Europeans. One of our friends brought director Bernardo Bertolucci to a party the day after his controversial film Last Tango in Paris opened in New York. I loved the movie. Bertolucci was and is a great artist and was very much the man of the moment. I found him as mysterious and arrogant as he was handsome in the red silk Saint Laurent shirt that Marina Schiano had given him that afternoon. We talked politics, not film or fashion, and ended up late at night discussing democracy and freedom. Like many Italian intellectuals, Bernardo was a Communist, which in America was considered shocking. I found him riveting.\ The momentum of my life with Egon covered up the differences that were growing between us, but we didn't discuss them. It all began to unravel at a ball we went to that was organized by Cecil Beaton in Dallas. I wore a Capucci dress with lots of ruffles on the skirt but very little on top. Newsweek ran a photograph of Egon and me with barely covered breasts in its Newsmaker section, a photograph that caught the eye of Clay Felker, the editor of New York magazine. The cover story he ran about us in New York under the headline "The Couple That Has Everything. Is Everything Enough?" forced me to look at our marriage. It did not look good. I was unhappy but rather than complaining about it, I was focusing on work.\ Egon admitted publicly to having affairs with other people, which was very painful to me, but I continued to smile and act cool. As a reaction, I started having a secret affair myself. It was my recognition of the loss of intimacy between us, the picture of superficiality that emerged from the story, that forced me to come to terms with the fact that our three-and-a-half-year marriage was over.\ When, shortly after the story ran in February 1973, Egon suggested that he get his own apartment, I encouraged him. He and I remained close friends. I never asked him for alimony. I have always resented women asking for alimony if they don't need the money, and by then I had the luxury and the great satisfaction of being able to support myself and my children. Money was never an issue between us.\ Besides, it was I who owed so much to him. Not only had Egon given me the children, the name, and the contacts that had opened so many doors but he had always supported my work and encouraged me. It was he who had insisted on having our children, which, left to my own decision, I might not have done. For that, I'll always be profoundly grateful.\ In the years to come, we would always spend Christmas together with the children, and they would often travel with him. At other times, we would travel all together. For the children's sake, I worked hard at keeping the relationship warm and real. I somehow always considered him my husband just as he considered me his wife, though he would remarry after we officially divorced in 1983. To this day he gives me a present for what would have been our anniversary. But, in truth, at the age of twenty-six, I became a single, working mother.

\ From Barnes & NobleNow available in a slightly updated version, Diane Von Furstenberg's wrap dress, a cultural phenomenon in the 1970s that hangs in the Smithsonian Institution, has sold more than five million. In Diane: A Signature Life, Von Furstenberg looks back at a groundbreaking career that shows no sign of slowing down.\ \ \ \ \ Michele Orecklin. . .[B]reezy reading for anyone who enjoys columns with a plentitutde of bold-faced names. \ —New York Times Book Review\ \ \ People MagazineYou have to hand it to Diane Von Furstenberg: She works hard for the money. . . .Still, her candor is endearing.\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyIn 1973, Diane Von Furstenburg introduced her now famous wrap dress, an outfit she estimates has "found its way into almost every closet in America," becoming a cultural icon, symbolic of women's growing sexual and financial freedom. Five years later, in 1978, the market appeared to be saturated with the dress and the era of the wrap came to a close. Today, Von Furstenburg has updated and reissued the dress for a new generation; launched fragrance, cosmetics and couture companies; and ventured into the home-shopping business. She asks that this memoir "inspire those who read it," and certainly the determination and verve with which she has overcome each setback in her life--be it a business reversal, a love affair turned sour or a cancer diagnosis--might prove inspirational to some. But despite the fascinating raw materials of her life (the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, she married a German prince, becoming a jet-setting socialite/entrepreneur/mother/paramour), this autobiography offers far more glitz than grist for thought. She drops names and brand names so interchangeably that we know not only who the celebrities are who buy her clothes but when the author received her first Pucci shirt. When Von Furstenburg reflects on her philosophy of life--"to me, life is love is life is love. I put those words on a T-shirt once"--readers may suspect that the real purpose here is to sell apparel. And sell it will. Photos not seen by PW. First serial to Vogue. (Nov.)\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsBuild a better dress and they will come: this is the theme of this celebrity autobiography by designer/jet setter Von Furstenberg. The daughter of a concentration camp survivor, 22-year-old Von Furstenberg was living in 1960s New York with her husband, German Prince Eduard Egon Von Furstenberg, when she introduced the dress that would make her a fashion icon and a millionaire in her own right. The wrap dress, she says, was 'nothing really. just a few yards of fabric with two sleeves and a wide wrap sash.' But it caught the imaginations of millions of women and even entered the Smithsonian Institution's pop culture collection. Von Furstenberg also worked hard, crisscrossed the country promoting her line of clothing, sometimes chasing a potential customer across the selling floor to insist the matron was not 'too old and too fat' to wear the dress. Although separated from her husband after less than four years of marriage, Von Furstenberg was devoted to her two children, characterizing herself as as 'a single, working mother.' Unlike most single mothers, she dined and danced at the White House, becoming friends with Henry Kissinger, California's former governor Jerry Brown, and movie mogul Barry Diller. When women's power suits and some unfortunate business decisions led to the decline of The Dress and of the value of her name, she sold it all (very profitably) and moved to Paris with an Italian novelist. There she ran a literary salon, welcoming writers from Alberto Moravia to Bret Easton Ellis. But business was where her talent lay; she returned to New York in 1989 and found her way onto QVC, a TV shopping channel, where in four years she sold $40 million worth of her designs. Shealso survived a bout with cancer.\ \