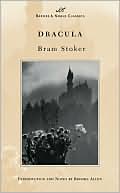

Dracula

Thanks to the huge success of the Twilight series, vampires have become the most popular supernatural creatures on earth. But Dracula is the one that started it all, back in 1897. Bram Stoker's eternally terrifying classic established the genre, with its looming Transylvanian castle; creepy undead bloodsuckers; innocent maidens in danger; and unforgettable characters, including the insane insect-eating Renfield. Dracula still thrills and chills today…and forever. \ \...

Search in google:

The punctured throat, the coffin lid slowly opening, the unholy shriek as the stake pierces the heart—these are just a few of the chilling images Bram Stoker unleashed upon the world with his 1897 masterpiece, Dracula. Inspired by the folk legend of nosferatu, the undead, Stoker created a timeless tale of gothic horror and romance that has enthralled and terrified readers ever since.A true masterwork of storytelling, Dracula has transcended generation, language, and culture to become one of the most popular novels ever written. It is a quintessential tale of suspense and horror, boasting one of the most terrifying characters ever born in literature: Count Dracula, a tragic, night-dwelling specter who feeds upon the blood of the living, and whose diabolical passions prey upon the innocent, the helpless, and the beautiful. But Dracula also stands as a bleak allegorical saga of an eternally cursed being whose nocturnal atrocities reflect the dark underside of the supremely moralistic age in which it was originally written — and the corrupt desires that continue to plague the modern human condition.Publishers WeeklyThis illustrated adaptation of Bram Stoker's work trades the epistolary nature of the original for a condensed, third-person narration, supplemented by selections from Jonathan Harker's journal entries and from John Seward's memoirs. Hitting the major plot points, like Jonathan's arrival at Dracula's castle and Lucy's frightening transformation, Raven retains much of the subtle terror of Jonathan's imprisonment, while providing Mina with more volition (" ‘Tonight we end this,' added Mina firmly"). Readers will likely be chilled by Gilbert's evocative ink and colored pencil images and drawn to the enigmatic Count, with his long, blond hair and violet eyes. A lavish and accessible retelling. Ages 12-up. (July)

From the Introduction By Joan Acocella\ \ 'Unclean, unclean!' Mina Harker screams, gathering her bloodied nightgown around her. In Chapter 21 of Bram Stoker's Dracula, Mina's friend John Seward, a psychiatrist in Purfleet, Essex, tells how he and a colleague, warned that Mina might be in danger, broke into her bedroom one night and found her kneeling on the edge of her bed. Bending over her was a tall figure, dressed in black.\ \ His right hand gripped her by the back of the neck, forcing her face down on his bosom. Her white nightdress was smeared with blood, and a thin stream trickled down the man's bare breast which was shown by his torn-open dress. The attitude of the two had a terrible resemblance to a child forcing a kitten's nose into a saucer of milk to compel it to drink.\ \ Mina's husband, Jonathan, lay on the bed, unconscious, a few inches from the scene of his wife's violation.\ \ Later, between sobs, Mina relates what happened. She was in bed with Jonathan when a strange mist crept into the room. Soon, it congealed into the figure of a man — Count Dracula.\ \ With a mocking smile, he placed one hand upon my shoulder and, holding me tight, bared my throat with the other, saying as he did so: 'First, a little refreshment to reward my exertions...' And oh, my God, my God, pity me! He placed his reeking lips upon my throat!\ \ The Count took a long drink. Then he drew back, and spoke sweet words to Mina. 'Flesh of my flesh', he called her, 'my bountiful wine-press'. But now he wanted something else. He wanted her in his power from then on. A person who has had his — or, more often, her — blood sucked repeatedly by a vampire turns into a vampire too, but the conversion can be accomplished more quickly if the victim also sucks the vampire's blood. And so, Mina says,\ \ he pulled open his shirt, and with his long sharp nails opened a vein in his breast. When the blood began to spurt out, he ... seized my neck and pressed my mouth to the wound, so that I must either suffocate or swallow some of the — Oh, my God!\ \ The unspeakable happened — she sucked his blood, at his breast — at which point her friends stormed into the room. Dracula vanished, and, Seward relates, Mina uttered 'a scream so wild, so ear-piercing, so despairing ... that it will ring in my ears to my dying day'.\ \ That scene, and Stoker's whole novel, is still ringing in our ears. Stoker did not invent vampires. If we define them, broadly, as the undead — spirits who rise, embodied, from their graves to torment the living — they have been part of human imagining since ancient times. Eventually, vampire superstition became concentrated in Eastern Europe. (It survives there today. In 2007, a Serbian named Miroslav Milosevic — no relation — drove a stake into the grave of Slobodan Milosevic.) It was presumably in Easter Europe that people worked out what became the standard methods for eliminating a vampire: you drive a wooden stake through his heart, or cut off his head, or burn him — or, to be on the safe side, all three. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, there were outbreaks of vampire hysteria in Western Europe; numerous stakings were reported in Germany. By 1734, the word 'vampire' had entered the English language. In 1750 the first scholarly treatise on the subject appeared — the work of Dom Augustin Calmet, a French Benedictine monk who devoutly believed in these monsters.\ \ In those days, vampires were grotesque creatures. Often, they were pictured as bloated and purple-faced (from drinking blood); they had long talons and wore dirty shrouds and smelled terrible — a description probably based on the appearance of corpses whose tombs had been opened by worried villagers. These early undead did not necessarily draw blood. Often, they just did regular mischief — stole firewood, scared horses. (Sometimes, they helped with the housework.) Their origins, too, were often quaint. Matthew Beresford, in his recent book From Demons to Dracula: The Creation of the Modern Vampire Myth, records a Serbian Gypsy belief that pumpkins, if kept for more than ten days, may cross over: 'The gathered pumpkins stir all by themselves and make a sound like "brrl, brrl, brrl!" and begin to shake themselves.' Then they become vampires. This is not yet the suave, opera-cloaked fellow of our modern mythology. That figure emerged in the early nineteenth century, a child of the Romantic movement.\ \ In the summer of 1816, Lord Byron, fleeing marital difficulties, was holed up in a villa on Lake Geneva. With him was his personal physician, John Polidori, and nearby, in another house, his friend Persy Bysshe Shelley; Shelley's mistress, Mary Godwin; and Mary's stepsister Clair Clairmont, was angling for Byron's attention (with reason: she was pregnant by him). The weather that summer was cold and rainy. The friends spent hours in Byron's drawing room, talking. One night, they read on another ghost stories, which were very popular at the time, and Byron suggested that they all right ghost stories of their own. Shelley and Clairmont produced nothing. Byron began a story and then laid it aside. But the remaining members of the summer party went to their desks and created the most enduring figures of the modern horror genre. Mary Godwin, eighteen years old, began her novel Frankenstein (1818), and John Polidori, apparently following a sketch that Byron had written for his abandoned story, wrote The Vampyre: A Tale (1819). In Polidori's narrative, the undead villain is a proud, handsome aristocrat, fatal to women. (Some say that Polidori based the character on Byron.) He's interested only in virgins; he sucks their necks; they die; he lives. The modern vampire was born.\ \ The public adored him. In England and France, Polidori's tale spawned popular plays, operas, and operettas. Vampire novels appeared, the most widely read being James Malcolm Rymer's Varney the Vampire, serialized between 1845 and 1847. Varney was a penny dreadful, and faithful to the genre. ('Shriek followed shriek....Her beautifully rounded limbs quivered with the agony of her soul....He drags her head to the bed's edge.') After Varney came Carmilla (1872), by Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu, an Irish ghost-story writer. Carmilla was the mother of vampire bodice-rippers. It also gave birth to the lesbian vampire story — in time, a plentiful subgenre. 'Her hot lips traveled along my cheek in kisses,' the female narrator writes, 'and she would whisper, almost in sobs, "You are mine, you shall be mine."' Varney and Carmilla were low-end hits, but vampires penetrated high literature as well. Baudelaire wrote a poem, and Théophile Gautier a prose poem, on the subject.\ \ Then came Bram (Abraham) Stoker. Stoker was a civil servant who fell in love with theatre in his native Dublin. In 1878, he moved to London to become the business manager of the Lyceum Theatre, owned by his idol, the actor Henry Irving. On the side, Stoker wrote thrillers, one about a curse-wielding mummy, one about a giant homicidal worm, and so on. Several of these books are in print, but they probably wouldn't be if it were not for the fame — and the afterlife — of Stoker's fourth novel, Dracula (1897). Dracula was not an immediate success. Its star rose only later, once it was adapted for the stage and the movies. The first English Dracula play, by Hamilton Deane, opened in 1924 and was a sensation. The American production (1927), with a script revised by John. L. Balderston and with Bela Lugosi in the title role, was even more popular. Ladies were carried, fainting, from the theatre. Meanwhile, the films had begun appearing: notably, F. W. Murnau's silent Nosferatu (1922), which many critics still consider the greatest of Dracula movies, and then Tod Browning's Dracula (1931), the first vampire talkie, with Lugosi navigating among the spider webs and intoning the famous words 'I do not drink...wine.' (That line is not in the book. It was written for Browning's movie.) Lugosi stamped the image of Dracula forever, and it stamped him. Thereafter, this ambitious Hungarian actor had a hard time getting non-monstrous roles. He spent many years as a drug addict. He was buries in his Dracula cloak.\ \ From that point to the present, there have been more than 140 Dracula movies. Roman Polanski, Andy Warhol, Werner Herzog, and Francis Ford Coppola all made films about the Count. There are subgenres of Dracula movies: comedy, pornography, blaxploitation, anime. After film, television, of course, took on vampires. Dark Shadows in the 1960s and Buffy the Vampire Slayer in the '90s were both big hits. Meanwhile, the undead have had a long life in fiction. The most important entrant in the late twentieth century was Anne Rice's Interview with the Vampire (1976), with its numerous sequels. Rice's heir was Stephenie Meyer, with her series of four Twilight novels, which, born in 2005, have sold an astonishing 85 million copies and generated a number of even more profitable movies. A runner-up was Charlaine Harris's collection of Sookie Stackhouse novels (Dead Until Dark and its sequels), about the passion of a Louisiana barmaid for a handsome revenant named Bill, and what she wore on each of their dates. This series, too, sold in the millions, and it spawned a television series called True Blood, with copious blood. In 2009 Dutton published Dracula: The Un-dead, co-authored by the fragrantly named Dacre Stoker (reportedly a great-grandnephew of Bram). It made the New York Times's extended best-seller list.\ \ Outside the mass media, as well, Dracula has had a strong following. There is a Transylvanian Society of Dracula, based in Bucharest, with chapters in several other countries. If you travel to Romania there are several Dracula-country tours you can take. (The Count has been a gold mine for the post-Ceausescu tourist industry.) Even if you go only as far as Whitby, the English seaside resort where, in Stoker's book, Dracula begins his Western campaign, you can have the 'Dracula Experience', an excursion through the sites of his malefactions there. On a blurred borderline with the fan action is vampire scholarship. In the 1920s, the English historian Montague Summers, a Roman Catholic priest (or, some say, a man impersonating a priest), published The Vampire: His Kith and Kin and The Vampire in Europe, obsessively detailed books that at times seem aimed not so much to inform readers as to give them bad dreams. At one point, Summers quotes a nineteenth-century source on ho certain Australian tribes treat their sick with the blood of the healthy. The latter open a vein in their forearms and let the blood run into a bowl: 'It is generally taken in a raw state by the invalid, who lifts it to his mouth like jelly between his fingers and his thumb.' Like Calmet, Summers believed in the existence of vampires, and pitied people who didn't.\ \ Later scholars, free of Christian faith, have bent the material to newer orthodoxies. In the mid-twentieth century, Freudian critics, addressing Stoker's novel, did what Freudians did at the time. More recently, postmodern critics, intent instead on politics — race, sex, and gender — have feasted at the table. Representative essays include Christopher Craft's '"Kiss Me with Thos Red Lips": Gender and Inversion in Bram Stoker's Dracula', Stephen D. Arata's 'The Occidental Tourist: Dracula and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization', and Talia Schaffer's '"A Wilde Desire Took Me": The Homoerotic History of Dracula'. There is a Journal of Dracula Studies.\ \ *\ \ What is all this about? One could say that Dracula, like certain other works — Alice in Wonderland, the Sherlock Holmes stories — is a cult favorite. But why does it have a cult? Well, cults often gather around powerful works of popular art. Fans feel that they have to root for them. What, then, is the source of Dracula's power? A simple device, used in many notable works of art: the deployment of great and volatile forces within a very tight structure.

PART I. THE COMPLETE TEXT IN CULTURAL CONTEXT The Complete Text Cultural Documents PART II. A CASE STUDY IN CONTEMPORARY CRITICISM Gender Criticism Sos Eltis Psychoanalytic Criticism Dennis Foster New Historicism Gregory Castle Deconstruction John Paul Riquelme Combining Critical Perspectives Jennifer Wicke

\ 1897 London Times reviewMonday August 23rdDRACULA cannot be described as a domestic novel, nor its annals as those of a quiet life. The circumstances described are from the first peculiar. A young solicitor sent for on business by a client in Transylvania goes through some unusual experiences. He finds himself shut up in a half ruined castle with a host who is only seen at night and three beautiful females who have the misfortune of being vampires. Their intentions, which can hardly be described as honourable, are to suck his blood, in order to sustain their own vitality. Count Dracula (the host) is also a vampire but has grown tired of his compatriots, however young and beautiful, and has a great desire for what may literally be called fresh blood. He has therefore sent for the solicitor that through his means he may be introduced to London society. Without understanding the Count's views, Mr. Harker has good reason for having suspicions of his client. Wolves come at his command, and also fogs; he is also too clever by half at climbing. There is a splendid prospect from the castle terrace, which Mr. Harker would have enjoyed but for his conviction that he would never leave the place alive-\ . . .\ These scenes and situations, striking as they are, become commonplace compared with Count Dracula's goings on in London. As Falstaff was not only witty himself but the cause of wit in other people, so a vampire, it seems, compels those it has bitten (two little marks on the throat are its token, usually taken by faculty for the scratches of a broach) to become after death vampires also. Nothing can keep them away but garlic, which is, perhaps, why that comestible is so popular in certain countries. One may imagine, therefore,how the thing spread in London after the Count's arrival. The only chance of stopping it was to kill the Count before any of his victims died, and this was a difficult job, for though several centuries old, he was very young and strong, and could become a dog or a bat at pleasure. However, it is undertaken by four resolute and high-principled persons, and how it is managed forms the subject of the story, of which nobody can complain that it is deficient in dramatic situations. We would not however, recommend it to nervous persons for evening reading.\ \ \ \ \ Children's Literature\ - Anita Barnes Lowen\ Almost everyone is familiar with the story of Dracula. Jonathan Harker, a young English solicitor, travels to Transylvania to finalize a real estate sale. He soon realizes that Count Dracula, his host and client, is not what he seems. "...what manner of creature is this in the semblance of a man?" Finding himself effectively imprisoned and discovering that he is promised to three female vampires ("...when I am done with him, you shall kiss him at your will") Harker escapes down the castle wall and knows no more. In England, a mysterious ship wrecks near the home of Lucy Westerna, a friend of Harker's fiancee. No crew, no captain...only a large dog that bounds overboard and disappears. Soon afterwards Lucy becomes pale and ill and unexplainable red marks appear on her throat. Her doctor is baffled and calls on his mentor, Van Helsing, who quickly surmises that Lucy has become one of the Undead and must be destroyed. "I shall cut off her head, fill her mouth with garlic, and I shall drive a stake through her heart." But the horror will not end until Dracula himself is found and destroyed. The story is told through journal entries and letters written by the novel's characters. At the end of the book, readers will find information on the author, major and minor characters, vampire myths, and vampire bats as well as suggestions of things to think about and do, and a glossary. With the current popularity of vampires in teen and young adult fiction, this chunky classic should be in every middle and high school library. Reviewer: Anita Barnes Lowen\ \ \ School Library JournalGr 5-9–For readers wanting a small shiver down their spines, these books will suffice. Stoker’s Dracula is succinct and well edited. The art is stale and tame and might titillate, but it won’t produce any nightmares. The adaptation in Dorian Gray can be clunky at times but it covers the main points of the story. The beautiful and youthful Dorian Gray is never very attractive in the illustrations, but the decaying painting will appropriately disgust young readers. The story in The Invisible Man is heavily edited, and the action is crammed into a few pages, but the scenes in which the Invisible Man is on the loose are intense. The illustrations are fairly detailed and include some graphic scenes of blood and a nearly naked Invisible Man. All three books include information about the authors and a glossary. There are better adaptations of these novels available, but these titles provide slim and chilling reads that give a taste of the actual stories for reluctant readers.–Carrie Rogers-Whitehead, Kearns Library, UT\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThis illustrated adaptation of Bram Stoker's work trades the epistolary nature of the original for a condensed, third-person narration, supplemented by selections from Jonathan Harker's journal entries and from John Seward's memoirs. Hitting the major plot points, like Jonathan's arrival at Dracula's castle and Lucy's frightening transformation, Raven retains much of the subtle terror of Jonathan's imprisonment, while providing Mina with more volition (" ‘Tonight we end this,' added Mina firmly"). Readers will likely be chilled by Gilbert's evocative ink and colored pencil images and drawn to the enigmatic Count, with his long, blond hair and violet eyes. A lavish and accessible retelling. Ages 12-up. (July)\ \ \ \ \ VOYA\ - Matthew Weaver\ The prospect of a remake of Bram Stoker's classic is, at first, frightening. This book, however, quickly quells any uneasiness with the first of many gorgeous illustrations. Gilbert's artwork is so lushly vivid and lovingly crafted—particularly the recurring bat imagery and a scene where a wolf drinks a young woman's blood—that it threatens to overpower the words altogether. As we advance through a story both familiar and fresh, heroine Mina waits for word from her fiance, Jonathan, who has gone to Transylvania to help a mysterious Count Dracula arrange housing in London. It's not long before the count has arrived and dear friend Lucy Holmwood falls gravely ill. Mina and Jonathan, with the aid of Professor Abraham Van Helsing, must work to rid themselves of the most famous vampire of all. Raven has rearranged Stoker's novel and made slight alterations to the story, including the addition of a gypsy boy who bears a long-standing vendetta against the infamous count, and a twist to the ending that would doubtless have sat well with the original author. In the midst of Twilight fervor, it must have been tempting to revisit Dracula as a tortured romantic figure, but aside from his new blond locks, there's plenty here to please longtime enthusiasts and welcome a whole new audience to a tale that, just as its central figure, refuses to die. Reviewer: Matthew Weaver\ \ \ \ \ From Barnes & NobleMysterious, gloomy castles and open graves at midnight are just two of the Gothic devices used to chilling effect in this 19th-century horror classic that turned an obscure figure from Eastern European folklore into a towering icon of film and literature.\ \