Exploring the Literature of Fact: Children's Nonfiction Trade Books in the Elementary Classroom

Filling a crucial need for K-6 teachers, this book provides practical strategies for using nonfiction trade books in language arts and content area instruction. Research-based, classroom-tested ideas are spelled out to help teachers:\ \ *Select from among the many wonderful nonfiction trade books available\ *Incorporate nonfiction into the classroom\ *Work with students to develop comprehension strategies for informational texts\ *Elicit responses to nonfiction through drama, writing, and...

Search in google:

Filling a crucial need for K-6 teachers, this book provides practical strategies for using nonfiction trade books in language arts and content area instruction. Research-based, classroom-tested ideas are spelled out to help teachers:*Select from among the many wonderful nonfiction trade books available*Incorporate nonfiction into the classroom*Work with students to develop comprehension strategies for informational texts*Elicit responses to nonfiction through drama, writing, and discussion*Use nonfiction to promote content area learning and research skills Unique features of the book include teacher-created lesson plans, extensive lists of recommended books (including choices for reluctant readers), illustrative examples of student work, and suggestions for linking nonfiction reading to the use of the World Wide Web.

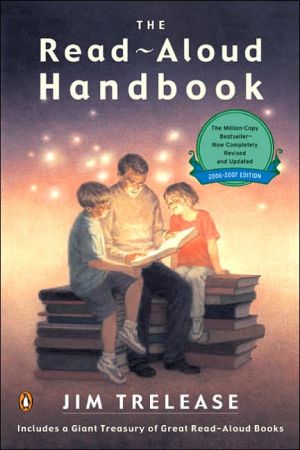

Exploring the Literature of Fact\ Children's Nonfiction Trade Books in the Elementary Classroom \ \ By Barbara Moss \ The Guilford Press\ Copyright © 2003 The Guilford Press\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 1-57230-546-0 \ \ \ Chapter One\ Bringing Nonfiction into the Classroom \ Photographer Nic Bishop produced the illustrations for The Red-Eyed Tree Frog (Cowley, 1999), which won the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award for the best picture book of 1999. This nonfiction title for young children depicts a tiny tree frog's quest for food and its close encounter with a hungry boa snake. With painstaking care, this talented artist created the stunning action photography that makes this book come alive. In his acceptance speech for the award, he reflected on his own bittersweet childhood experiences with books both in and out of school:\ When I reached back into my own childhood, I remembered that my bookshelf was filled only with nonfiction titles. As a young boy, I was always more enchanted by the natural world than the imagined. At school, I would rarely read past page three of a fiction story before I was glancing out of the window, my mind drifting to the world outside. Certainly, I was one of those children who didn't respond to reading fiction. (Bishop, 2000)\ As Bishop notes, nonfiction is the recreational reading of choice for some children. Outside of school, these children, likeBishop, may love reading because they can choose books of interest to them. In school, however, they may be reluctant readers-mainly because their book choices are constrained by lack of access to nonfiction. As Vardell and Copeland (1992) note: "Although our everyday lives are filled with observations about the world around us, we often neglect the opportunity to engage children in learning about that world. We introduce our children to great storybooks and novels, forgetting the fascination of facts" (p. 76).\ Many children get little or no opportunity to read nonfiction in their classrooms. Duke (1999) examined the uses of informational texts in early-grade classrooms. To gather information for her study, she visited 20 different first-grade classrooms for four full days during one school year. She collected information about the types of texts on classroom walls and other surfaces, in classroom libraries, and in written language activities. She found a scarcity of informational texts in these classrooms-children averaged only 3.6 minutes per day interacting with this type of text. Furthermore, only 9.8% of the books in the classroom libraries were informational.\ This chapter explores ways teachers can make nonfiction literature a natural part of classroom literacy learning experiences. The first section of this chapter focuses on reading nonfiction aloud. It provides a rationale, gives suggestions for selection and planning of nonfiction read-alouds, and recommends interesting formats for this activity. The second section suggests ideas for making nonfiction part of the classroom reading environment. It recommends ways to incorporate nonfiction literature into sustained silent reading time and classroom libraries. It also suggests ways teachers can pique interest in nonfiction through displays, centers, book talks, author visits, and technology. The last section of the chapter identifies five ways teachers can organize the classroom for more formal study of nonfiction literature.\ READING NONFICTION ALOUD\ Teachers often express concerns about how to begin to use nonfiction in the classroom. Reading nonfiction aloud is an easy way to get started in using this genre. Reading aloud is a familiar, comfortable activity for both teachers and students. Most importantly, it is of inestimable value for students of all ages. This section offers a rationale for reading nonfiction aloud and suggestions for selecting and planning nonfiction read-alouds. It also recommends effective read-aloud formats and identifies and discusses a number of excellent nonfiction read-aloud titles.\ Why Read Nonfiction Aloud?\ Daily reading aloud is the simplest, least expensive, and most often recommended practice for improving student's reading achievement. The link between reading aloud and academic success has been well established. Reading aloud to children exposes them to new words, new expressions, and new concepts. It helps them internalize the structures of written language used to create every text genre. It promotes familiarity with language that serves children well as they read and write independently. According to Chambers (1995), as children listen to prose of all kinds, they unconsciously absorb the rhythms, structures, and cadences of the various forms of written language. They are developing understanding of how print "sounds." It is only through hearing words in print being spoken that children discover their "color, their life, their movement, and drama" (Chambers, 1995, p. 130).\ Narrative literature is usually the preferred genre for teacher read alouds. A 1993 survey of teacher read-aloud practices in 537 elementary schools validates this point (Hoffman, Roser, & Battle, 1993). While the identified titles included excellent fantasy and realistic fiction, none of the most frequently read books at any grade level were nonfiction.\ Why should teachers expand the read-aloud "canon" to include nonfiction? What are the benefits of reading nonfiction aloud?\ First, nonfiction read-alouds draw children into the magic of the real world-of predators and prey, of planets and space exploration, of other times, lands, and lives. Exposure to nonfiction read-alouds has the ripple effect of a pebble tossed into a pond. It expands children's knowledge, which adds to their schema about an infinite number of topics. This in turn ultimately enhances comprehension. It teaches children concepts and terms associated with topics, places, and things they may never encounter in real life (Moss, 1995).\ Second, reading nonfiction aloud sensitizes children to the organizational patterns found in nonstory text. Children of all ages are well aware of the structure of story. Even so, they have little knowledge of common non-narrative patterns like cause-effect, problem-solution, description, and enumeration. By hearing nonfiction read aloud, children begin to internalize these structures. Consequently, they become better able to comprehend these structures as they read and model them in their own writing.\ Third, nonfiction read-alouds provide excellent links to fictional texts. For example, after hearing the adventures of Babe: The Gallant Pig (King-Smith, 1983), children would probably enjoy another book by the same author, All Pigs Are Beautiful (King-Smith, 1995), which provides information about pigs. These experiences can lead to discussions about similarities and differences in the two genre, ways the information in each book complements the other, and the process the author used to create each book.\ Nonfiction read-alouds can also provide powerful connections to curricular content. Listening to titles like Red Scarf Girl: A Memoir of the Cultural Revolution (Jiang, 1997) during a social studies unit on China can personalize a distant and unfamiliar culture in a way that no textbook can. This moving memoir describes how Ji Li Jiang, a young teenager in the 1960s, gradually becomes disillusioned with the Chinese government she has been taught to revere. Her life unravels as the Cultural Revolution and its propaganda destroy the lives of many innocent people, including her family. An excellent student and class leader, she is denounced for her intelligence and family background. Government officials search her home, steal precious family possessions, and imprison her father. Ultimately she must choose between her family and the revolutionary government in power. Her story offers much to think about in terms of the role of government, the power of propaganda, and the conflict between political and family considerations.\ Finally, and most importantly, nonfiction read-alouds whet children's appetites for information. As Seymour Simon, a noted nonfiction author, states, "I'm more interested in arousing enthusiasm in kids than in teaching facts. The facts may change, but the enthusiasm for exploring the world will remain with them the rest of their lives" (personal communication, 2001). Through this enthusiasm, children may feel compelled to learn more about areas of intense personal interest, which can lead to further silent, independent reading of this and other genres.\ Selecting and Planning Read-Alouds\ What is the best way to select nonfiction titles appropriate for reading aloud? First, consider the quality of the book in terms of the five A's discussed in Chapter 2: (1) the authority of the author, (2) the accuracy of the text, (3) the appropriateness of the book for children, (4) the literary artistry, and (5) the appearance of the book (Moss, 1995).\ Another essential factor to consider is the author's voice. Does the book's author speak to readers? Can children "hear" the person behind the information, or do they just hear fact piled upon fact? It's important also to select books that "ignite the imagination, as if children were indeed fires to be lit" (Carr, 1987, p. 710). Overly technical books or those overloaded with unfamiliar concepts will put off even the most enthusiastic listeners.\ A third consideration pertains to children's interests and curricular relevance. Knowing the students, their interests, and their background experiences is the key to successful read-aloud selection. The interest inventory in Chapter 2 can help teachers identify topics that their students will enjoy hearing about. Teachers who not only know their students but also know what they want to know, can locate books that captivate children of any age.\ Although all nonfiction read-alouds need not relate to the curriculum, many titles can boost children's understanding of subjects like science, social studies, health, art, music, or mathematics. Nonfiction read-alouds can provide interesting in-depth information on almost any classroom topic, as well as current issues such as the environment, cultural diversity, global warming, or AIDS.\ Suggested Read-Aloud Titles\ Figure 3.1 lists examples of good primary-, intermediate-, and upper-grade nonfiction read-alouds. Many of the primary titles listed contain captivating illustrations that provide support for text information. In Growing Vegetable Soup (Ehlert, 1987), for example, the brightly colored collage illustrations of the various vegetables are sure to captivate kindergarten and first-grade listeners. Lynn Cherry's (1992) A River Ran Wild, a book suitable for reading aloud to older primary graders, traces the history of the Nashua River from the settlement of its valley by Indians 7,000 years ago until its recent reclamation. Each double-spread illustration depicts a period or topic mentioned and is bordered with tiny illustrations of wildlife, artifacts, or scenes of the Nashua River area in north central Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire.\ Many of the upper-grade read-alouds listed contain photographs, maps, and primary source documents that lend authenticity to text information. In Into the Mummy's Tomb: The Real-Life Discovery of Tutankhamun's Treasures, for example, author Nicholas Reeves (1992) uses maps of Egypt, cutaway diagrams of Tut's pyramid and tomb, and dramatic color photographs that help youngsters appreciate the splendor of these treasures.\ Formats for Nonfiction Read Alouds\ All too often, classroom read-aloud experiences are isolated and unrelated to other classroom work. Nonfiction read-alouds could be easily correlated to classroom content. In classrooms where teachers use inquiry units (see Chapter 6), for example, read alouds can introduce, culminate, or extend units of study. During a unit on the presidency, for example, Julie Allison read So You Think You Want to Be President? (St. George, 2000) aloud to her fifth-grade class. Full of interesting and amusing anecdotes, this Caldecott Medal winner explores the characteristics of Presidents present and past. It also examines the advantages and disadvantages of the presidency from a child's point of view. Advantages include having a swimming pool, a movie theater, and not having to eat broccoli, while disadvantages include having to dress up, be polite, and do lots of homework.\ Nonfiction read-alouds could be linked with books from other literary genre on similar or related topics. Many elementary teachers, for example, read Charlotte's Web (White, 1952) aloud. Spider Watching (French, 1996), a Candlewick Press nonfiction title, perfectly complements Charlotte's Web. Left-hand pages of the book define scientific terms and spiders' physical characteristics, while right-hand pages tell a story of a young girl who overcomes her initial fear of spiders. Children can compare the contents of each book by using a Venn diagram. They might consider the purposes of each author and the ways each book achieved those purposes. From these experiences children develop understanding of the imaginative forms of fiction and the creative shaping of facts required for writing nonfiction.\ Teachers might read aloud different books about the same person, place, or event. An intermediate-grade teacher could read Abraham Lincoln (D'Aulaire & D'Aulaire, 1939), F. N. Monjo's (1973) Me and Willie and Pa: The Story of Abraham Lincoln and His Son Tad, and Myra Cohn Livingston's (1993) poem Abraham Lincoln: A Man for All the People-A Ballad. In this way, children can examine different authors' points of view about this extraordinary man's life. The first title, an early Caldecott Medal winner, is an "idealized" version of Lincoln's life. It avoids mention of the assassination, since this fact was considered too harsh for inclusion in a children's book in the 1930s. The second title provides glimpses of life in the White House through the eyes of Lincoln's son Tad. It is narrated in first person in the vernacular of a youngster living in the 1860s. The third work, a narrative poem, uses Lincoln's own words to portray his life. Following these readings, children could compare the form of each book, the points of view each author took toward its subject, and the information each chose to include or exclude.\ Most books mentioned so far in this section are best read in their entirety. Many nonfiction titles, however, are not appropriate for cover-to-cover reading. For this reason, teachers may want to model reading aloud "bits and pieces" of books. Dotty Lane, a first-grade teacher in Columbus, OH, often reads small, interesting sections of "browser" books like the Eyewitness Junior series aloud. After these short readings, she closes the book.\ \ Continues...\ \ \ \ Excerpted from Exploring the Literature of Fact by Barbara Moss Copyright © 2003 by The Guilford Press. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Introduction Chapter 1. Exploring the Nonfiction Genre Chapter 2. Choosing Nonfiction Trade Books Chapter 3. Bringing Nonfiction into the Classroom Chapter 4. Helping Students Read Nonfiction Strategically Chapter 5. Guiding Student Response to Nonfiction Chapter 6. Content Area Learning through Nonfiction Appendix: Orbis Pictus Award-Winning Books Index

\ From the Publisher"This text should be required reading for all preservice and inservice elementary teachers who want to use nonfiction trade books effectively in their teaching. Moss's explanations, examples, and classroom-tested strategies help teachers understand how to select and use nonfiction texts throughout their curriculum. The classroom descriptions, student work samples, and practical suggestions make this book a valuable resource that will be useful for professional development programs, children's literature courses, and content area reading courses."--Laurie Elish-Piper, PhD, Department of Literacy Education, Northern Illinois University\ "While the past decade has seen an explosion in the availability of nonfiction trade books for the elementary grades, teachers' knowledge and use of these important resources has lagged behind. This book takes a significant leap forward in closing the gap between fiction and nonfiction in teachers' knowledge and classroom usage. Moss, one of the country's leading scholars in this area, provides teachers, teacher educators, and literacy educators with an in-depth, comprehensive treatment of how to use nonfiction to improve students' achievement and motivation. The many teaching suggestions provided are clearly detailed, user-friendly, classroom proven, and applicable in nearly any content area. This book is a 'must' for any teacher or teacher educator interested in making nonfiction trade books an integral part of the elementary school curriculum."--Timothy Rasinski, PhD, Department of Teaching, Leadership, and Curriculum Studies, Kent State University\ "A real gold mine! This book goes beyond the recommendations for teaching nonfiction literature found in most texts. Moss addresses the environmental and instructional factors necessary for helping students learn to read, write, and love the literature of fact in constructive, inquiry-oriented classrooms. Readers will appreciate the abundance of practical classroom activities presented within the context of a rich theoretical framework and a current research base--all written in an engaging conversational style. Another bonus is found in the many citations of notable, current nonfiction titles. This book will serve as an excellent text for nonfiction children's literature courses in university settings, and as a wonderful resource for elementary teachers."--Terrell A. Young, EdD, Department of Teaching and Learning, Washington State University\ \ \ \