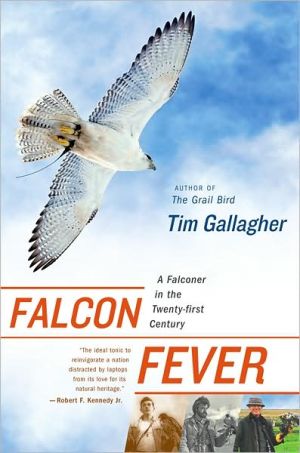

Falcon Fever: A Falconer in the Twenty-First Century

What is so compelling about falconry? Tim Gallagher mines his lifelong obsession with falcons for an answer in this engaging volume interweaving memoir, history, and travelogue. An entire subculture of the sport exists outside the mainstream of American society, consisting of obsessed individuals who still use the ancient training techniques and language of falconry. Gallagher finds that his personal story connects on many levels with that of Frederick II, the thirteenth-century Holy Roman...

Search in google:

What is so compelling about falconry? Tim Gallagher mines his lifelong obsession with falcons for an answer in this engaging volume interweaving memoir, history, and travelogue. An entire subculture of the sport exists outside the mainstream of American society, consisting of obsessed individuals who still use the ancient training techniques and language of falconry. Gallagher finds that his personal story connects on many levels with that of Frederick II, the thirteenth-century Holy Roman Emperor, legendary falconer, and notorious freethinker who brought the full wrath of the medieval Church down upon his dynasty. While following in Frederick’s footsteps through southern Italy, Gallagher ponders his own history as well. What salve to his spirit did falconry provide when it ignited his passion at age twelve? Beset by a turbulent childhood dominated by a brutal and violent father, Gallagher turned to this sport for emotional release. He offers us a unique glimpse into contemporary falconry, and the result is a surprisingly frank and revealing personal story. Kirkus Reviews The editor in chief of Living Bird magazine writes about his favorite feathered friends. Noted for tracking down the famously elusive ivory-billed woodpecker (The Grail Bird, 2005), ornithologist Gallagher is also an ardent falconer. His boundary-stretching memoir chronicles coming of age with birds of prey. Reared in a bleakly dysfunctional family, the author discovered in adolescence a lifelong idol: Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, author of the classic text on keeping and training raptors. Gallagher's admiration for Frederick gave rise in later years to an Italian tour in homage to his hero. He offers a report on what he did on that vacation, the interesting spots he missed and the crafty locals who took his luggage. It was depressing, but the author discovered good cheer as well during soulful trips to famous grouse moors, meetings and group hunts with colorful, world-class falconers. Indeed, most of his book concerns adventures and fellowship with the artists who train and run these darting and diving feathered hunters. Falconry is an art, Gallagher declares, proffering a rapturous vision of the sport that has spanned continents and millennia, in addition to his recollections of all the old fowlers and birds he will never meet again. Tiercel prairie falcons, Cooper's hawks, Gyrfalcons and buteos throng his pages, as do the tools of the trade: hoods, creances, swivels, jesses and, recently, telemetry devices. Pigeons, ducks, mice and rabbits are clobbered, albeit with grace and intelligence, in a narrative quite red in beak and claw. Gallagher's favorite bird is named Macduff, but it's readers not totally enraptured with hunting birds perched on gauntleted fists who are likely to bethe first to cry "Hold, enough!"Enthusiasts will love it; others may grow bored. Agent: Maria Carvainis/Maria Carvainis Agency

INTRODUCTION\ “You’re nothing but a falconry bum, and I never want to see you again,” she said, slamming the telephone down. By then it was almost midnight. I was supposed to have had dinner with her at seven o’clock and meet her parents for the first time. We’d been planning the dinner for almost a month. Instead, I was huddled shivering in a phone booth beside a field, covered in mud and swamp water from searching all day for my lost falcon. That was almost forty years ago, when I was seventeen. The sad thing is, I never got the falcon back—or the girlfriend. And this was not the first (or last) time something like that happened to me. For many years, this was the story of my life—a person who lived and breathed to hunt game with trained hawks and falcons. I’ve been a falconer for a very long time. I can’t say why exactly, but something about falconry completely captured my passion and spirit as a twelve-year-old and has held me enthralled ever since. I think about what drew me to falconry more and more as I get older. As a kid, I always loved nature, and I’d been training and handling various animals—dogs, parakeets, frogs, toads, snakes, lizards, pigeons, sparrows—since early childhood, but for me, from the time I first put a falcon on my fist, no other interest ever came close to competing with falconry. Even when I quit flying birds of prey for a few years at one point in my life, falconry was always there, lying just below the surface like an incurable affliction temporarily in remission. Why is that? What is it about my personality that makes me so susceptible to this kind of obsession—an addiction really? And what is it about falconry that seems to attract such over-the-top devotees? An entire subculture exists outside the mainstream of American society consisting of people like me who still use the ancient training techniques and language of falconry. I suspect almost any of us could communicate effectively with most medieval falconers if we happened to be dropped somehow into a twelfth- century hawking establishment. But we are not some kind of creative anachronism society. We borrow freely from both ancient and modern techniques, equipment, and medical expertise to train and care for our birds. We just love raptors and thrill to see them hunt game. There aren’t many of us—just a few thousand in the United States—but I can’t think of any group as enthusiastic about their endeavor as falconers. I’m sure psychologists would have a field day examining our addiction. I’m still trying to puzzle it out myself. Of course, the birds are beautiful. To my mind, nothing else in nature rivals the power and elegance of a raptor in flight. Most people who see a wild falcon dive at prey remember the sight for the rest of their lives—the sheer speed, the roar of the wind through the bird’s flight feathers, the frightening violence. I’m sure that’s all part of the lure of these birds for me, but there is so much more. I’ve never been the kind of person who takes the killing of an animal lightly. I love animals. I’m fascinated by everything about them, and I’ve spent much of my life observing and photographing nature—a passive witness to its wondrous spectacle. But when I’m flying a raptor, I’m a different animal, as fierce and determined as a rampaging wolverine to flush game for my bird. If falconry didn’t exist, I would probably never have become a hunter. That’s but one of the many paradoxes in my life I’m still working out. The magical, intuitive bond that develops between a falconer and a trained raptor is a great attraction for me and is one of the things that keeps me getting up before dawn, day after day, on workdays and weekends, through autumn and early winter, trudging through the fields in all kinds of weather to fly my eight-year-old peregrine falcon, Macduff. I named him after the Shakespearian character who killed Macbeth in a ferocious fight at the end of the play. “Lay on, Macduff,” says Macbeth in his famous last words. “Damned be he who first cries, ‘Hold. Enough.’ ” That’s just the way I feel about it. As long as Macduff is willing to keep flying hard, soaring high above me and hammering game in blistering vertical power dives, I’ll be damned if I quit hunting with him. As I step into his flight chamber to pick him up on this blustery December morning in 2005, he flaps his wings powerfully, eager to fly. I lift him quickly onto my gauntleted fist, slip a leather hood on his head to keep him calm, and carry him out to my car. While most of my neighbors still lie sleeping, I load up my gear and drive away in search of game. This morning is more special than most. Exactly 755 years earlier, on December 13, 1250, Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Sicily and Jerusalem, departed this life. I’m sure few took time to note this anniversary, besides a handful of eccentric falconers like me, who feel a bond with Frederick that has endured through the centuries. You see, Frederick II is like the patron saint of falconry—although the Catholic Church is unlikely to grant him sainthood any time soon; he spent most of his life at odds with a succession of popes and was excommunicated twice. He was a lifelong falconer as well as a scientist, scholar, poet, and architect, and he authored a massive tome on falconry, De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (On the Art of Hunting with Birds), that is still a useful guide for training falcons. You could say I’ve been obsessed with Frederick II for most of my life—really for as long as I’ve been a falconer. I consider Frederick to be the spiritual forebear of all falconry bums. He lived the life of a transient monarch, with no single city to call his home: just a series of castles and hunting lodges he visited to go hawking. It’s a telling fact that he suffered the worst defeat of his entire reign when he went off hawking during the siege of Parma, leaving his camp lightly defended. The people of the besieged city stormed the camp, slaughtering Frederick’s soldiers, burning everything to the ground, and stealing his entire treasury—a staggering defeat that he never really got over. It sounds like something I might have done.\ IT IS A chilly morning and several inches of snow lie on the ground as I drive through the low wooded hills and farmland surrounding Ithaca, New York, making my usual game-hawking circuit, checking ponds and small creeks for ducks. Frederick called hunting ducks with a falcon “hawking at the brook.” His falconry treatise—a classic medieval illuminated manuscript—has a beautiful hand-painted illustration of a medieval falconer who has stripped naked and is swimming across a lake to get to his peregrine, sitting on a duck kill on the other side of the water. I’m hoping I won’t have to do that today in the subfreezing weather, but you never know. Some of the ponds I visit are already frozen, but I know of a few spring-fed ponds and running creeks that usually have open water well into winter. At the first pond, in a vast open field surrounded by woodlands, I spot at least two mallards, though it’s difficult to see most of the pond because of its high banks and the trees and shrubs along the sides. A mallard is big for Macduff to tackle, weighing more than twice as much as he does. A female peregrine would be more appropriate for mallard hawking. As with most hawks and falcons, male peregrines are about one third smaller than female peregrines and better suited for catching smaller quarry. (The correct term for a male falcon is tiercel, which comes from the French word tierce, meaning “third.”) But Macduff has taken many mallards over the years, and I’m sure he’ll put on a good effort whether he catches a duck or not. Parking my car behind the trees, I walk quietly down a path through the woods. It’s quiet. The only sound is the breeze whistling through the canopy of the trees and the high-pitched tinkle of the brass bells on Macduff ’s legs. Falconers have used bells like these for centuries to help locate their birds whether they are flying high above or sitting in cover on a kill. Macduff also wears a tiny radio transmitter, which is like a high-tech bell I can use to track him down from several miles away with a telemetry receiver. When I reach the edge of the field, I slip off Macduff ’s hood and hold him into the wind. He shakes his feathers, looks quickly around in all directions as he flaps his wings, and explodes powerfully from my fist. He flies straight away from me for nearly a hundred yards, then starts circling upward, pumping his wings hard to gain altitude as quickly as possible. If the ducks or other game spot a falcon before it has gained enough altitude to make an effective stoop (or power dive), they some- times flush prematurely and slip away to safety. That won’t happen today. He’s already high enough to keep them sitting tightly in the water. I take a moment to evaluate the situation—to figure out the direction and strength of the wind and which angle of attack would make the most sense. Should I flush from the east side of the pond or the west? Which would give my bird the best chance to catch a duck? A falcon has to know that its trainer is an effective tactician in the field. If I’m always flushing game at the wrong time or in a bad situation—or failing to find game at all—a falcon will quickly lose respect for my abilities and go off hunting for itself. What would Frederick have done in this situation? I opt to approach the pond from the east side, giving my bird a downwind stoop on the mallards. By this time, Macduff is so high I have a hard time spotting him as he flies in broad circles that are more than a hundred yards wide. I finally see him, a tiny speck right above me, breasting the wind like a gull. I break for the pond, sprinting as fast as I can in my neoprene chest waders. I keep low to the ground, bent over to stay out of sight below the raised bank of the pond. Taking a last look at Macduff to make sure he’s in a good position, I charge the pond, leaping over the side and plunging up to my waist in the icy water with a great splash. A dozen mallards—far more than I had seen—burst from the other side of the pond. I know this will be good. Macduff is still circling, almost like the ducks aren’t there. But it’s just a tactical maneuver; he doesn’t want to commit to a stoop if there’s a chance the birds will drop back into the safety of the pond. (Once ducks do that, it’s difficult to flush them again.) The ducks make three or four circles, seventy feet above the pond, and then break away across the open field, headed for a nearby river. I lose sight of Macduff as he folds up and turns downward, going into a powerful stoop. A second later, I spot him again with my ten-power binoculars as he plummets earthward, and I hear the amazing whistle of wind blowing through his flight feathers. When he hits the duck—a huge drake mallard—with his feet, it sounds like the crack of a Major League batter hitting a home run. The duck does three or four somersaults and slams into the ground, while my falcon pulls up from the dive, swooping up perhaps two or three hundred feet with his wings held back, then drops down onto the duck. I run to him as fast as I can, in case I need to help out. But it’s all over; Macduff is biting the back of the duck’s neck, severing its spinal cord with his powerful bill. It’s a nice moment sitting on the ground beside a falcon on a kill. To me, it’s one of the wonders of falconry that a bird this innately wild would accept my presence so completely. I reach over and help hold the dead mallard as he plucks its feathers. A few minutes later, I slip my fingers inside the duck’s chest cavity and pull out its heart, which falcons relish, holding it out for him to eat, steaming in the frosty morning air. After letting him feed on the duck for a short time, I lift him onto my fist with a piece of meat I had in my game bag, while hiding the duck carcass from view. Using a falconer’s sleight of hand, I accomplish this without Macduff suspecting for an instant that he’s been robbed. I intend to take the rest home for a duck dinner with my family. It’s only eight a.m., and I’ve already had a great flight to start my day. In another half hour, I’ll be back to everyday life, driving to work, and Macduff will be sitting puffed up on his perch, well fed and contented. It sounds easy, but not every day goes like this. Far more often, I come home with an empty game bag. Hundreds of things can go wrong in falconry. But catching a lot of game is not the reason I fly hawks. “The falconer’s primary aspiration should be to possess hunting birds that he has trained through his own ingenuity to capture the quarry he desires in the manner he prefers,” wrote Frederick II. “The actual taking of prey should be a secondary consideration.” These are words I live by. If I wanted to kill a lot of ducks, I’d get a shotgun. New York State’s bag limit for mallards is currently four per day, a number that can easily be reached with a firearm. With a falcon, I’m happy if I take one. For me, seeing a great flight is everything, whether the falcon catches its quarry or not. Some people say it’s unfair and cruel to attack poor, defenseless waterfowl with a trained falcon. Ducks are anything but defenseless—especially when pitted against a predator like a falcon with which they’ve evolved side by side for countless millennia. All of the world’s wild animals are hard-wired with strategies for survival. Mallards are big and fast and tough. They can take a hard pounding and escape unscathed. It’s an enormous challenge for Macduff to tackle and hold a mallard. Smaller ducks have different strategies. Green-winged teal are quick and slippery; they can turn on a dime and will throw themselves hard onto the ground and come out flying in the opposite direction, leaving a falcon baffled. Pintails are intelligent and spooky, making them more difficult to approach. I’m endlessly fascinated by what animals will do to escape a predator; it is in those situations that you see them at their best. I rarely have any regrets when a duck or other prey eludes my falcon. To me, falconry at its highest level is an art form in which the canvas is the entire sky. For my part as a falconer, I set everything up and let the falcon complete the work of art. I’m not the first person to describe falconry as an art. Again, that would be Frederick II, who considered falconry the noblest of arts. When I first became interested in falconry as a twelve- year-old in the early 1960s, the only book on the subject I could find at the local library was a 1943 edition of Frederick’s book, which translators Casey A. Wood and F. Marjorie Fyfe titled The Art of Falconry. It took months, but I read it from cover to cover and then went back to study the sections that interested me most. What an amazing piece of literature. It covers much more than falconry—it is a scientific work of the first order and one of the first works of ornithology, looking at the behavior, anatomy, and physiology of birds. I view Frederick as an old friend. Through his book, written in the thirteenth century, he taught me how to train falcons. I made my first jesses (the thin leather straps put on a falcon’s legs) from his patterns. I took my first game with a falcon using his carefully written advice. But more than that, I think Frederick II—and the sport of falconry he championed—helped me through some of the most trying times in my life. I believe if it were not for falconry I would not be alive today. As I sat in the field with Macduff on the anniversary of Frederick’s death, I was fifty-five years old—the same age as Frederick when he passed away. Besides being a sobering reminder of my own mortality, it made me think there would never be a better time to take stock of who I am and to examine the central role falconry has played through most of my life. Did I have an innate affinity with birds of prey that made it inevitable for me to become a falconer? I used to think so. Or was falconry just a way for me to escape a brutal, depressing childhood—a way to create my own private world, forging deep relationships with the wildest, freest creatures in nature? I didn’t know the answers to any of these questions, but I wanted badly to find out. At that moment an idea started taking shape in my mind. I would begin a personal quest, examining experiences in my life that I’d blocked from my mind for decades. I would spend a year on a journey of self- discovery, using falconry and Frederick II as keys to my psyche. To accomplish this, I knew I would first have to trace my earliest memories as a boy in England and relive my many personal trials and tragedies. It would not be easy—at times it would be harrowing—but I knew it was the only way I would ever come to a full understanding of who I am and why. A lot of people will be surprised by the revelations I unveil in this book—especially those who didn’t know me when I was growing up and got into serious trouble with the law. I have since become what most would consider a model citizen, working at a respected university and raising my family in an idyllic farm village in upstate New York. It wasn’t always like that. During my year of personal exploration, I decided I would immerse myself in falconry in a way I had not done since my teens and twenties. I saw it all taking shape in my imagination. I would travel to Wyoming and watch falconers hunt hard-flying winter sage grouse—perhaps the pinnacle of the sport in modern times. I would visit the heather-covered Highlands of Scotland and see trained peregrine falcons stoop from the clouds at red grouse as my falconry forebears had done for ages. I would go crow hawking on horseback in northern England, watching the dark birds circle up into the sky with a falcon in pursuit. I would attend the annual field meet of the North American Falconers’ Association as I had done as a sixteen-year-old some forty years earlier. And I would finish by traveling through the fertile lands of southern Italy that Frederick adored, visiting the place where he was born, the place he died, the amazing castles he built, and finally the red porphyry sarcophagus that holds his earthly remains to gain a fuller understanding of what falconry and Frederick II mean to me. This would be my Frederick II year, an exploration of the inner workings of my own mind and spirit and the nature of the art that Frederick and I share. Why was I drawn to predatory birds at such an early age? Why did they become such an overwhelming passion, eclipsing everything else in my life? What was it that made me want to join falcons in the chase—to hunt other animals with them? I can’t explain it, but I know Frederick felt the same sense of awe and mystery about falconry as I; I’m only following in his footsteps.

CONTENTS Introduction 1PART I MY BACK PAGES 1 2 Rex and Rowdy 30 3 The Biker 43 4 Blow Up 57 5 Flying Free 70 6 Centerville Days 80 7 The Long Spiral Downward 93 8 Desolation Row 107 9 O Tank 122PART II MY FREDERICK II YEAR 10 In Frederick II’s Footsteps 147 11 Winter in Wyoming 158 12 Highland Fling 174 13 A Born-Again Falconer 193 14 Forty Years After 207 GallagherFalcFev_i-x_1-326.indd ix 2/12/08 1:45:36 PM 15 The Saracen Citadel 231 16 The Eye of Apulia 247 17 Jewel of the Hill 256 18 On to Sicily 264 19 Palermo without a Map 273 20 The Hawks of Herculaneum 283 21 See Rome and Die 294 22 Homeward Bound 310Epilogue 319 Acknowledgments 323

\ Kirkus ReviewsThe editor in chief of Living Bird magazine writes about his favorite feathered friends. Noted for tracking down the famously elusive ivory-billed woodpecker (The Grail Bird, 2005), ornithologist Gallagher is also an ardent falconer. His boundary-stretching memoir chronicles coming of age with birds of prey. Reared in a bleakly dysfunctional family, the author discovered in adolescence a lifelong idol: Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, author of the classic text on keeping and training raptors. Gallagher's admiration for Frederick gave rise in later years to an Italian tour in homage to his hero. He offers a report on what he did on that vacation, the interesting spots he missed and the crafty locals who took his luggage. It was depressing, but the author discovered good cheer as well during soulful trips to famous grouse moors, meetings and group hunts with colorful, world-class falconers. Indeed, most of his book concerns adventures and fellowship with the artists who train and run these darting and diving feathered hunters. Falconry is an art, Gallagher declares, proffering a rapturous vision of the sport that has spanned continents and millennia, in addition to his recollections of all the old fowlers and birds he will never meet again. Tiercel prairie falcons, Cooper's hawks, Gyrfalcons and buteos throng his pages, as do the tools of the trade: hoods, creances, swivels, jesses and, recently, telemetry devices. Pigeons, ducks, mice and rabbits are clobbered, albeit with grace and intelligence, in a narrative quite red in beak and claw. Gallagher's favorite bird is named Macduff, but it's readers not totally enraptured with hunting birds perched on gauntleted fists who are likely to bethe first to cry "Hold, enough!"Enthusiasts will love it; others may grow bored. Agent: Maria Carvainis/Maria Carvainis Agency\ \ \ The Barnes & Noble ReviewYou'd think Falcon Fever is just a book for bird lovers. After all, it tells the story of one man's obsession from childhood on with training birds to hunt, the ancient art of falconry. But this memoir, written earnestly by the author of the bestselling Grail Bird and editor of Living Bird magazine, is much more than a treatise on the joys of birding. Tim Gallagher exposes us to the most excruciating moments of his life, such as when he spent a childhood evening endlessly rehearsing with his father's gun how he would murder the abusive alcoholic and then kill himself, getting as far as chambering the bullet and aiming it at dear, old drunken Dad. But the life story pursues birds as they pursue prey. Gallagher's historical explorations offer a grand tour of falconry's ancient and recent past, giving pride of place to the life of Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, the 13th-century Holy Roman Emperor who wrote what some consider falconry's bible, On the Art of Hunting with Birds. Stuffed with fascinating asides -- the phrase ?fed up," for example, comes from falconry -- Gallagher's book maps a connection between past and present: ?What was it that made me want to join falcons in the chase -- to hunt other animals with them?? he writes. ?I can't explain it, but I know Frederick felt the same sense of awe and mystery.? Frederick and his story become a shadow that is always finding new ways to reappear in this fascinating look at a lively subculture too often unnoticed in America. --Mark J. Miller\ \