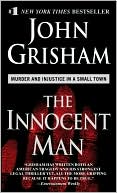

Finding Life on Death Row: Profiles of Six Inmates

Joseph Carl Shaw, a military policeman who suffered from schizophrenia and attempted to medicate himself with illegal drugs, committed three murders after being turned away from a mental health clinic; a court-appointed lawyer advised him to plead guilty and put his fate in the hands of a politically ambitious judge who sentenced him to death. Judy Haney was convicted of killing a man who had abused her and her children; she was represented by a lawyer who appeared in court so drunk that the...

Search in google:

"In this disturbing book, Lezin puts a human face on the debate about capital punishment." — Publishers Weekly Publishers Weekly Executions in the U.S. are usually carried out with little fanfare, and the public rarely knows much about who is being killed in its name. In this disturbing book, Lezin, a freelance writer who used to work at the office of career services at the Georgetown University Law Center, puts a human face on the debate about capital punishment. Her even-handed presentations of the cases of six death-row inmates, drawn from the files of Stephen Bright, director of the Southern Center for Human Rights, introduce readers to the inmates, the victims, the families, horrible crimes and horrible judges. As attorney Bright notes in his informative foreword, "A society that employs such an enormous, severe, irreversible, and violent penalty, which has been discarded by much of the rest of the world, should at least know whom it is killing." All six cases here are from the South: one is a woman, two have already been executed. The variety of their backgrounds and circumstances serves to highlight many of the injustices inflicted upon minorities, women and the poor. Lezin admits her bias at the outset, stating that she is "adamantly opposed to the death penalty" and that Bright assisted "with all aspects of researching and writing" the book. But Lezin presents each case with no commentary beyond a brief preface. Still, the facts make a compelling argument that the system is too riddled with discrimination and injustice to be morally or constitutionally sound. (Sept.) Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ Dear Karyn,\ It was about 4:30 when I pulled into the drive way. You were in the back yard wearing a halter top and cut off blue geans. In the back yard was a swing set and a sand box. The grass was green and the yard was fenced in. When I opened the gate, Jennifer, our little girl came running to me and said your home daddy. I picked her up and gave her a kiss and said yes I'm home. I then walked over to you and kissed you. You asked me how my day was and I said fine. I had a present for Jennifer because it was her birthday. When we got into the house she ran to get her report card. It had all A's and B's on it. I told her that she had done very good in school. You had cooked a meat loaf for supper. After supper the cake and ice-cream was brought out. It has 7 candels on it. After we ate the cake and ice-cream she opened her presents. It was a yellow dress with yellow ribbons for her pony tail. She had a great big smile on her face and said thank you to you and me. It was now about 9:30. We looked at each other and said it was time to go to bed for ourselves. We turned all the lights off except for the bathroom light in case Jennifer woke up in the middle of the night. We sat in bed for about 15 minutes and talked about how lucky we were to have a daughter like her. I reached over to give you a hug and a kiss, but before I could kiss you the guy next to me woke me up and said it was time for chow. I hope part of this dream comes true for you Karyn because I know now it will never happen to me because now I am in Jail for killing 3 people. I'll probably be dead ina year because they want to give me the death penalty, so I hope you can find a life like the one I wrote about Karyn.\ Love,\ J.C.\ \ \ J.C. Shaw married Karyn Negrich, his high school sweetheart, on March 31, 1973. It was his eighteenth birthday. Their wedding photo shows a young white man with abundant dark hair, long sideburns, and a thick mustache. His large hands hang at the sides of his six-foot-three-inch frame as if he doesn't know what to do with them, and he has the slightest hint of a smile on his face. His bride, looking much more like her eighteen years, is beaming. The proud parents flank the newlyweds on both sides, all clearly happy with the match.\ Following the wedding, J.C. moved from the house he shared with his mother, stepfather, and three half-brothers to his in-laws' home. He and Karyn were happy on the Gibson farm. J.C. helped Karyn's father and grandfather with the farm work, and the young couple often babysat Karyn's little brother, Tim.\ Babysitting younger brothers was not new to J.C. He was eight when Robert Jr., the first of his three half-brothers, was born. Robert Jr. was followed by Dennis three years later, and by Gregory one year after Dennis. Since both parents worked outside the home, J.C. helped raise his younger brothers, often caring for them in his parents' absence. All three boys looked up to J.C. and loved him, but Robert Jr. revered him most. He and J.C. shared a room, and Robert Jr. spent most of his free time shadowing his big brother. He tagged along to J.C.'s basketball games and later, when J.C. bought his first car with money he'd borrowed from his parents, Robert Jr. hitched rides with J.C. to his own basketball games. He still remembers the ride back from the game in which he scored a basket for the opposing team. Completely devastated, Robert Jr. was convinced he could never show his face again, but J.C. was able to tease him and console him in a way that no one else could.\ J.C. was a generous and involved older brother. He coached Robert Jr.'s Little League team and even let Robert accompany him and Karyn on a double date, despite the eight-year age difference between them. J.C. spent hours wrestling with his brothers down in the basement, and always referred to them as "the kids." Even when Robert Jr., Dennis, and Greg were out of high school, J.C. continued to call them "the kids." One Christmas, his parents told him he would not be getting much that year because money was tight. "Don't worry," J.C. responded. "Just buy for the kids."\ Joseph Carl Shaw was born on March 31, 1955, to Melvin and Mary Shaw in Louisville, Kentucky. By the time he was three, his parents were divorced. The following year, his mother married Robert Crum, her second husband. J.C.'s father maintained some contact with him until his eighth birthday, but abandoned him alter that. J.C. was a happy child, but very fidgety and hyperactive. Drugs were prescribed early on to calm him down. He also suffered from sudden high temperatures, some as high as 107 degrees, which sent him into convulsions.\ Over six feet tall by the time he was thirteen years old, J.C. was the tallest and largest boy in his class. His height served him well in sports, which he pursued much more enthusiastically and successfully than his school work. He was one of the better players in the Catholic basketball league for the city of Louisville, and he also excelled on the football field. At school, though, J.C. struggled to get C's. After flunking a grade, J.C. eventually dropped out of high school. He had completed the tenth grade. "For some reason" he later explained, "I just didn't get along with school work. School for me just didn't work out. I don't know why."\ His first job after leaving school was as a bag boy at a local supermarket. Within a short while, however, J.C. joined his stepfather finishing drywall. He was a hard worker and a good "wipe down" man; he and Robert Sr. enjoyed working together. He also enjoyed playing practical jokes on his stepfather, who often fell for J.C.'s pranks. Once J.C. called and pretended to be a homeowner wanting a quote on how much it would cost to paint his house. Robert Sr. made it through several rounds of questions before realizing that it was J.C. Later, when J.C. was in the Army, he would call from the corner store but pretend that he was still in South Carolina.\ Despite growing up during a time when rebellion was the norm, J.C. was respectful and loving toward his parents. He stuck to his 11:00 P.M. curfew (even though Karyn, whom he was dating at the time, had a 1:00 A.M. curfew), kept his room neat, and willingly watched "the kids" each day until his parents returned home from work. The only time he ever asked his parents for anything was when he borrowed money for his first car just before he got married. They told him he would have to pay them back a little money each month, and he did so without any further prompting.\ For the first twenty-one years of his life, J.C. never hurt anyone. He attended church regularly as a youngster, and was even an altar boy until he entered the eighth grade. He was thought of as a quiet, well-mannered, and gentle young man. His basketball coach remembers that J.C. was afraid to play hard during practice for fear of hurting one of his teammates, since he was so much bigger than they were. His high school principal recalls that he was "helpful to the smaller students in the school, and would always lend a helping hand when and where needed." Many of the letters later written on J.C.'s behalf described him as a "good boy" who "didn't have a mean bone in his body." In 1985, days before his scheduled execution, J.C. was asked by a reporter how he wanted to be remembered:\ I'm just sort of easygoing and if you need help, I'll give you the shirt off my back. I don't know if I will be remembered by too many people in this state other than for what they believe I am now. But for my friends and family, I just want to be remembered for being a family member. And I hope that anybody who can remember my past can forget what happened seven years ago.\ \ \ . . . . . . . .\ \ \ J.C. had always wanted to join the Army. He finally enlisted after his first year of marriage, but was turned down when a physical examination revealed a cyst at the base of his spine. Not to be deterred, he had an operation to remove the cyst and reapplied. After basic training at Fort Knox, Kentucky, J.C. was stationed at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina. He soon developed an interest in the Military Police (MP), and sought admission to the Military Police school at Fort Gordon, in Savannah, Georgia. He graduated on May 14, 1975.\ At first, J.C. loved the Army. The official photo of J.C. in his MP uniform shows a man who was proud to serve his country. And the Army was pleased with him as well. On December 15, 1976, he received a letter of commendation for his work at Fort Jackson.\ J.C.'s disillusionment with the Army began with his discovery that he was not being paid the amount to which he was entitled. It took a long time to straighten out his salary, and J.C. grew increasingly frustrated with the Army's bureaucracy. Even after his pay was corrected, he and Karyn had trouble meeting their financial obligations. In addition, J.C. never got the promotion that he was due as a result of his letter of commendation. What cemented his dismay with the Army, however, and hastened his attempts to secure his release, was Karyn's miscarriage. For reasons that are still unclear, Karyn and J.C. were denied treatment at the base hospital when J.C. rushed Karyn there for the pains she was experiencing early in her pregnancy. As J.C. later described it, "The Army wouldn't treat her. They said she was pregnant when I took her to the emergency room. They said we had to go to the Ob/Gyn because she was pregnant, and they couldn't do nothing for her." By the time they arrived at the nearby hospital to which they were referred, Karyn had lost the baby.\ Both J.C. and Karyn were grief-stricken by their loss. They were also faced with mounting bills. Shortly after the miscarriage, J.C. was involved in an unfortunate incident that ended up costing him his job as an M.P. He was riding in a friend's car, and they were stopped upon arriving at Fort Jackson, under suspicion of transporting drugs. J.C. protested his innocence, but was advised to sign an Article 15, the Army's version of a plea, rather than risk a court-martial. The presiding colonel ended up dropping the case, saying there was no evidence to justify stopping J.C. and his friend in the first place. But J.C.'s company commander demoted him because he had signed the Article 15. J.C. was no longer allowed to carry a gun or be a posted guard. In order to make ends meet, Karyn took a waitressing job at a nearby Shoney's restaurant. She soon began an affair with the assistant manager there, which J.C. inadvertently learned about from his stepfather.\ "Money's so tight that Karyn has to work double shifts" he told Robert Sr. on the phone one day. "Lately she goes in at 5:00 A.M. and doesn't get home until the following night?"\ "Sounds like she's fooling around on you, son" Robert Sr. told him, but J.C. didn't want to hear it.\ "Oh no, she would never do that" he insisted.\ A few days later, he called back, totally crestfallen. He had seen the assistant manager driving his and Karyn's car, and that was all the confirmation he needed. He and Karyn separated.\ Robert and Mary knew their son was depressed. Karyn had been his whole life, and the separation devastated him. Mary worried about him, but Robert always reassured her. "There's no better place he can be, honey" he'd say. "The Army takes care of its soldiers. They'll look after him?'\ Karyn moved back home to Kentucky. J.C. did just about everything he could to try to get her to come back. He called her incessantly, often in the middle of the night. He also reached out to her sister and mother, both of whom liked J.C., asking them to try to convince Karyn to return to him.\ After Karyn left him, a married couple with whom J.C. was friendly moved in to help him with the rent. J.C., who had always let Karyn handle the bills, was happy to comply with the arrangement they proposed of giving them his share of the rent and letting them take care of everything. The landlord's eviction notice, giving J.C. ten days to vacate the premises for nonpayment of rent, arrived the same day his so-called friends disappeared. J.C. returned home a few days later to find all of his clothes and furniture gone. Not knowing where else to turn, he moved back to Fort Jackson and to the Army life he now hated.\ . . . . . . . .\ The first indication Robert and Mary Crum had that the Army was not, in fact, looking out for their son was a call they received from J.C.'s new housemate in August 1977. For a second time, J.C. had taken an overdose of sleeping pills. The military hospital pumped his stomach but did not admit him for observation.\ Mary, who was terrified of flying, got on the next plane to go get J.C. She instinctively knew he would be okay if she could just get him home, but the most the Army would agree to was a three-day pass.\ At first, all J.C. wanted to do was sleep. "They've got me so doped up," he kept saying. But "the kids" soon had J.C. back to his old self, wrestling in the basement and cracking jokes. When Robert Sr. drove J.C. to the airport at the end of the three days, he was relieved to note that J.C. seemed to be in good spirits.\ "I know you're having a hard time with Karyn leaving you, but there are other fish in the sea," Robert Sr. assured him. "You're a good-looking guy. You'll get over this."\ J.C. nodded in agreement, not wanting to dispel his stepfather's misguided belief that he shared his optimism. Earlier, he had tried to convince Robert Jr. to go back with him to Fort Jackson and stay a while, but he had declined. Much later, reflecting on J.C.'s request, Robert Jr. regretted his decision to stay behind.\ The next time the family saw J.C. was in early October 1977. Contact with him had been sporadic since his three-day visit in August, and Mary was distressed that J.C. had not even bothered to call her on her birthday. She had fumed about it all day, but was delighted to find J.C. at home waiting for her when she returned from work. He was in high spirits because Karyn, with whom he had been trying to reconcile, had agreed to go back to Fort Jackson with him. On the day before he was due to leave, Karyn called and said she had changed her mind. That ended the visit. J.C. left in a hurry, barely managing to say good-bye. The Crums later learned that J.C. had been AWOL (absent without leave).\ Shortly after this visit, the Crums moved from Jefferstown, Kentucky, to Pee Wee Valley, in the same state. Robert Sr. wrote J.C. informing him of the move and assuring him that he would always have a home with them.\ \ \ . . . . . . . .\ \ \ Throughout the year following his separation, J.C. received counseling at the Fort Jackson Mental Health Center. Depression was not J.C.'s only problem. He told his parents that he needed to see a doctor about his ears. When they asked him what exactly was wrong with his ears, he responded, "What people are saying is not what I am hearing." He also turned to drugs and alcohol, experimenting with marijuana, cocaine, PCP, LSD, crystal methadone, mushrooms, speed, downers—anything he could.\ Every morning, J.C. would wake up and smoke several joints on the way to work. When he came home for lunch, he would take Percodan and Valium, which helped him get through the rest of the workday. On his way home, he would pick up a case of beer, which he and his roommate would consume along with whatever drugs happened to be available. As he later described it, "The only way I could live with myself was not to live with myself."\ His circle of friends spent their time together getting high. J.C., twenty-two at this point, shared a house with Robert Neil Williams, one year his junior. The two were often visited by James Terry Roach, a seventeen-year-old, and Ronald Eugene Mahaffey, a sixteen-year-old. Even though J.C. was the oldest, he was not the leader; that role was filled by Roach. The four could often be found at J.C.'s and Robert's home, sharing the drugs that they had purchased together.\ J.C.'s misery was given a brief respite when he began a relationship with a woman with whom he worked. The relationship progressed quickly, allowing J.C. to begin to envision a life without Karyn. His new girlfriend left the Army so that she could move in with J.C., and they began to look at rings together. But before J.C. could present her with the ring, she left. Perhaps it was because of his drug use; although it was tempered when he was with her, it never ceased. Perhaps it was because he still heard voices telling him what to do, particularly when he was tripping on PCP. Perhaps it was because he was still obsessed with Karyn. For whatever reason, the relationship ended abruptly on October 16, 1977.\ J.C.'s only coping mechanism at this point was losing himself in drugs and alcohol, which he did all that night and the following day. As he did so, the voices intensified. They told him to get back at Karyn and all women who could hurt him. They told him to get revenge. Williams, Roach, and Mahaffey were also there, sharing his drugs and his rage. By nightfall on October 17, 1977, their drug-induced ranting evolved into a plan to go out and find a woman to rape.\ \ \ . . . . . . . .\ \ \ Betty Swank's life had not been an easy one. Shuffled from one foster family to another, she longed for stability and love. She found what she was after in Albert Swank, whom she married at age sixteen. By the time she was twenty-one, she was the proud mother of a fifteen-month-old son. She finally had the family she had craved growing up. But the marriage was not without its problems. Betty and Albert were struggling on Albert's meager military salary, and to help make ends meet, Betty reluctantly took the night shift at a manufacturing plant. Jittery by nature, she hated driving at night. She usually picked up a friend who shared her midnight shift so that she wouldn't have to drive alone.\ On October 17, 1977, Betty left her home as usual to pick up her friend. She never made it. Thinking that her tire had suddenly blown out, Betty pulled into the parking lot of Roach's Market. The tire had actually been shot out by the four men who offered to give her a ride to her friend's house. Once inside the car, she saw the gun hidden under the back seat, but it was too late. She was kidnapped, raped, and shot. She was found murdered in the same mobile home park where her own trailer was located, shot twice with a .22 caliber pistol. She had made the mistake of recognizing one of her captors. "Aren't you stationed at Fort Jackson with my husband?" she asked J.C. Shaw.\ After they had all raped Betty, they offered her a ride home. She accepted, thinking that the worst had already happened to her. She asked if she could sit up front with J.C. telling him he was the only one she felt she could trust. J.C. dropped her off where she had requested, thinking as he did so that she looked a lot like Karyn. He drove about a hundred yards before the voices started in, prodding him to kill her. J. C. swerved the car around and returned to Betty. He called her over to the car, pulling out his gun as she approached. His three friends in the back yelled out in surprise as he shot her, but at least the voices were quiet.\ \ \ . . . . . . . .\ \ \ Earline Raffield, the receptionist at the Fort Jackson Mental Health Clinic, saw many troubled young men. But on Friday, October 28, 1977, there was something particularly urgent about the young soldier who came in pleading to be committed. He was dressed in civilian clothes and identified himself as J.C. Shaw.\ "I've got to see a psychiatrist" he said repeatedly. "He's got to put me on the ward"\ Raffield referred him to one of the psychiatrists on duty, who saw the distraught man for approximately fifteen minutes before sending him on his way.\ That afternoon, the man returned, even more visibly upset than before.\ "I've got to see somebody" he pleaded with her. "I'm afraid of what might happen. I'm afraid of what I might do."\ Raffield was the only staff member on duty. The rest of the Mental Health Clinic staff was in the backyard, enjoying a beer and hotdog party. Impressed with J.C.'s desperation and urgency, Earline went outside to the party and interrupted the festivities. She explained to Lieutenant Spradlin, a social worker, that this was Mr. Shaw's second visit to the clinic that day and his second request for help.\ J.C. was again seen for fifteen minutes before being dismissed. As he left through the reception area, Raffield found herself wishing they could have done more for him.\ \ \ . . . . . . . .\ \ \ Carlotta Hartness and Tommy Taylor were boyfriend and girlfriend, and the two teenagers seemed to have a lot in common. They attended a highly regarded private school about five miles north of where Betty Swank was murdered. Both came from wealthy families prominent in Richland County, South Carolina. And both fourteen-year-old Carlotta and seventeen-year-old Tommy were unusually dependable and responsible.\ On Saturday, October 29, 1977, the teens took off in Tommy's white Oldsmobile to do some research for a school paper Tommy was writing about his county's beautiful historic district. When neither Carlotta nor Tommy had telephoned by that evening to explain why they were late, their parents knew something was wrong. At 3:55 A.M. the next morning, their fears were confirmed. Tommy was found slumped over on the front seat of his car, shot twice in the head. At 2:30 P.M. that afternoon, Carlotta's mutilated corpse was discovered in a wooded area northwest of Columbia. She had been shot five times in the back of the head and raped. The autopsy revealed that a number of injuries were also inflicted on her body postmortem.\ \ \ The voices were at it again. They told J. C. to go back to the dead girl's body and tear it up. Doing so would relieve this terrible pressure. They promised him he would feel the same relief he felt after shooting Betty Swank; that same sense of fulfilling an obligation. When he arrived at the spot in the woods where they'd left her to die, he was actually surprised to see her. She still looked alive, and J.C. was half expecting her to sit up and ask him why they had done those terrible things to her. He closed her eyes, knowing he couldn't do what he was supposed to do to her with her staring at him, even in death. The voices then guided him to a broken bottle nearby, which he used to do the things to her that they told him to do.\ \ \ . . . . . . . .\ \ \ Robert Jr. was the one who answered the phone. He could tell right away there was something wrong with J.C. He called to his father to take the upstairs line. Robert Sr., upon hearing it was J.C., was relieved that he had called. He was sure it was in response to the letter he had sent J.C. about the move. When he picked up, however, J.C. had something entirely different to discuss. Robert Jr. listened on the downstairs line while J.C. told his stepfather that he was in jail for murdering three people.\ At first, Robert Sr. was convinced that this was yet another one of J.C.'s practical jokes. "Come on, J.C." he kept saying. "Stop fooling around." But Robert Jr. knew all along that it was no joke. He could just tell.\ Robert Sr. kept telling J.C. not to hang up. "Your mother's due home from work any minute now, and I want her to hear this from you, not me."\ When Mary walked up the front steps, Robert Jr. ran out to meet her at the front door. "J.C.'s on the phone," he said breathlessly. "He's in jail."\ Once his parents hung up the phone, Robert Jr. could hear them still trying to convince themselves that it was all a joke and that J.C. would be calling back any minute. They even went so far as to call the South Carolina jail from which J.C. had ostensibly called to make sure he was actually being held there. He could tell when they finally accepted the terrible news because they were both suddenly very quiet.\ Robert Jr. went into his room and shut the door. He sat on the edge of the bed in the room he had shared with his big brother. He put his face in his hands and cried.\ \ \ . . . . . . . .\ \ \ Soon the Crums' neighbors and relatives arrived at the house. They tried to console the devastated family, but they were all too shocked themselves to offer much comfort. Uncle Charlie focused on the practical issue of J.C.'s legal representation.\ "You don't want him to have one of those court-appointed attorneys" he insisted. "They're no good. You need to hire a first-rate lawyer"\ Uncle Charlie didn't know anyone in South Carolina, but he knew a local attorney who could probably recommend someone. Through him, Robert and Mary got the name of an experienced criminal lawyer in South Carolina, who agreed to look into the case for five hundred dollars. It was a lot of money, but it would be worth it if it helped them get their son back. The attorney met with Robert Sr. a few days later and told them he was willing to take the case. He informed him that he couldn't get J.C. off, but he could guarantee that J.C. wouldn't get the death penalty.\ "How much?" Robert Sr. asked.\ "Twenty thousand dollars, up front"\ Robert Sr. was stunned. He had no hope of getting that kind of money together. The Crums had had a hard enough time coming up with the initial five hundred dollars. They reluctantly said farewell to the recommended attorney—and their five hundred dollars—and tried instead to reassure themselves about J.C.'s court-appointed counsel. He was, after all, a prominent local attorney. The case had received so much publicity that the judge had appointed Kermit S. King, a successful and highly regarded member of the South Carolina bar, to represent J.C. Unbeknownst to the Crums, however, King's reputation was built on his record as a divorce attorney. This was not only his first capital case, but his first criminal case of any kind.\ \ \ . . . . . . . .\ \ \ Mary didn't know whether or not the room was bugged. It would explain why J.C. was acting so strangely. She was prepared for him to break down and cry or pound his fist in anger, but she didn't know what to do with this stiff and wooden stranger. When she hugged him, it was like hugging a fencepost. He had barely spoken to them since they had arrived at the jail. She told him to write down whether he'd really done those awful things. She was sure he was simply scared that they would use whatever he said against him. That's why he was being so quiet. But J.C. never even picked up the pen and paper she proffered.\ Robert and Mary tried to talk to King, but he made it clear he would not discuss the case with them. "You're not the client," he informed them. "J.C. is." They soon learned that this meant they could not have any input on his decisions or case strategy. They wanted to talk to King about his approach to the case. They didn't understand why he was encouraging J.C. to plead guilty. They knew their understanding of the law was murky at best, but they could not comprehend how J.C. would benefit from pleading guilty to the exact crimes with which he was charged. They wanted to ask him why he wasn't going to let J.C. go before a jury. Surely that would be better than letting a single man decide his fate, a man who, it was later revealed, had aspirations for higher office and was handling a highly publicized case. But the Crums' opinions were neither sought nor welcomed. King's insistence on a plea so early on in the case, with minimal investigation and a client whom King himself described as "a functional mute," was apparently based on King's belief that the only way J.C. could get a life sentence rather than the death penalty would be for the judge to accept his plea.\ "I gave Judge Harwell a leather jacket last year for Christmas," King told J.C. "So he owes me one"\ The whole family came down for the plea. Gregory did not want to go. He had been acting out at school since the night J.C. called from jail. Once they arrived in South Carolina, Dennis wanted to go home. Only Robert Jr. wanted to be there. He didn't understand what had happened to J.C., why his big brother was acting like he had a shell around him. But he still wanted to be with him.\ When J.C. pled guilty to the Hartness and Taylor murders, he did so with the stipulation that he did not pull the trigger. Mary was able to draw some consolation from the fact that Judge Harwell accepted J.C.'s plea. That must mean he believed her son. J.C. may have been there, but he didn't do the actual killings. King later confirmed to the Crums that J.C. had steadfastly maintained that he had not shot either of the teens, but that he had admitted to killing Betty Swank. The murder pleas were entered on the theory that J.C. was guilty of felony murder under the doctrine that the "hand of one is the hand of all."\ J.C. never testified or made a statement at his brief sentencing hearing. He did not contest codefendant Ronald Eugene Mahaffey's testimony that it was James Terry Roach who shot both victims, but that J.C. had taken a final shot at Carlotta Hartness after Roach had shot her several times.\ At one point, Judge Harwell asked J.C. if he had anything to say. "Yes" J.C. responded. He wanted to express to the judge how bad he felt about what had happened. He wanted to tell him that the relief he'd felt after the crimes was now replaced with shame and regret. He wanted to say he was sorry. But before he could articulate any of those things, his lawyer jumped in.\ "He has nothing to say, your Honor" he pronounced. "He misunderstood the question."\ It all happened so fast. Only six weeks elapsed from the time the crimes were committed to the time J.C. was sentenced to death. At his sentencing, J.C. sat as if in a trance. His brothers all watched him and marveled at how perfectly still he sat. He stared straight ahead and never changed his position throughout the entire proceeding. The newspapers all described him as "wooden" and "without any signs of remorse." His court-appointed attorneys (who included, in addition to Kermit King, Dallas D. Ball and W. Thomas Vernon) were quoted as saying that J.C. was "an exceedingly difficult man to talk with and to communicate with."\ Much later, when the psychiatrists who had observed and evaluated J.C. between his plea and his sentencing reported their findings, it was clear J.C. was neither mute nor intentionally uncommunicative. He was suffering from a severe case of clinical depression.\ (Continues...)

ForewordixPrefacexviiAcknowledgmentsxixJ.C. shaw1Donald Wayne Thomas45Michael cervi65Judy haney99Jimmy lee horton129Larry heath161Glossary187

\ Publishers Weekly - Publisher's Weekly\ Executions in the U.S. are usually carried out with little fanfare, and the public rarely knows much about who is being killed in its name. In this disturbing book, Lezin, a freelance writer who used to work at the office of career services at the Georgetown University Law Center, puts a human face on the debate about capital punishment. Her even-handed presentations of the cases of six death-row inmates, drawn from the files of Stephen Bright, director of the Southern Center for Human Rights, introduce readers to the inmates, the victims, the families, horrible crimes and horrible judges. As attorney Bright notes in his informative foreword, "A society that employs such an enormous, severe, irreversible, and violent penalty, which has been discarded by much of the rest of the world, should at least know whom it is killing." All six cases here are from the South: one is a woman, two have already been executed. The variety of their backgrounds and circumstances serves to highlight many of the injustices inflicted upon minorities, women and the poor. Lezin admits her bias at the outset, stating that she is "adamantly opposed to the death penalty" and that Bright assisted "with all aspects of researching and writing" the book. But Lezin presents each case with no commentary beyond a brief preface. Still, the facts make a compelling argument that the system is too riddled with discrimination and injustice to be morally or constitutionally sound. (Sept.) Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ BooknewsProfiles of six convicted murderers on Death Row show how an array of factors often leads people to commit capital crimes, and how perfunctory treatment by judges and court-appointed attorneys often leads them to Death Row. Compelling portraits of both men and women underscore the question of whether the death penalty is more often imposed on the poorest and most vulnerable perpetrators rather than the worst criminals. The author is former Assistant Director for Government and Public Interest at the Office of Career Services at the Georgetown University Law Center. She is now a freelance writer. Lacks a subject index. Annotation c. Book News, Inc., Portland, OR (booknews.com)\ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsLezin, a former assistant director at Georgetown University Law Center's career services office, presents a nuanced, original broadside against the death penalty. Her study takes the form of six dramatic narratives of condemned prisoners whose cases have been addressed by attorney Stephen Bright in his capacity as director of the Southern Center for Human Rights. In building evidence toward the fundamental barbarity and illogic of the death sentence, she begins by establishing that, at least statistically, our embrace of it darkly stains the US (when compared to the majority of industrialized nations). She provides six disturbing examples of the grim equation of political expedience, public vengeance, poverty, and misfortune that often result in the ultimate punishment. Some defendants were genuinely unhinged from undiagnosed schizophrenia or drug addiction during their crimes; nearly all were initially represented by incompetent, apathetic, or drunken attorneys. Particularly in the southern states' "death belt" (from which these cases are drawn), such mitigating factors as long-term neglect, retardation, or in one case a battered woman's imminent danger were rarely considered, and arguably, ambitious judges bettered their political records through liberal use of the death sentence. Lezin provides surprisingly sympathetic portraits of the six inmates (two since executed, one eventually freed), particularly making efforts to highlight ways in which these individuals have paradoxically bettered themselves, as in the case of "the apostle of death row," who was electrocuted in Georgia even after numerous appeals by the clergy. These personal narratives are interspersed with reconstructionof the lengthy legal maneuvers which the attorney teams pursued for their mostly destitute clients. Relatively little consideration is given to the ramifications for victims' families, making this book unlikely to be popular among their advocates. Still, the author takes an incendiary subject—the lives of those deemed fit to be killed by the state—and defuses it with a sensitive, humanistic, and sustained treatment.\ \