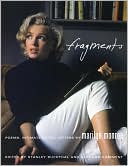

Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom: James Dean, Mel Gibson, and Keanu Reeves

Author Bio:\ Michael DeAngelis is Assistant Professor at the School for New Learning at DePaul University.

Search in google:

Why and how does the appeal of certain male Hollywood stars cross over from straight to gay audiences? In Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom Michael DeAngelis responds to these questions with a provocative analysis of three famous actors--James Deans, Mel Gibson, and Keanu Reeves. In the process, he traces a fifty-year history of audience reception that moves gay male fandom far beyond the realm of "camp" to places where culturally unauthorized fantasies are nurtured, developed, and shared. DeAngelis examines a variety of cultural documents, including studio publicity and promotional campaigns, star biographies, scandal magazines, and film reviews, as well as gay political and fan literature that ranges from the closeted pages of One and Mattachine Review in the 1950s to the very "out" dish columns, listserv postings, and on-line star fantasy narratives of the past decade. At the heart of this close historical study are treatments of particular film narratives, including East of Eden, Rebel Without a Cause, The Road Warrior, Lethal Weapon, My Own Private Idaho, and Speed. Using theories of fantasy and melodrama, Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom demonstrates how studios, agents, and even stars themselves often actively facilitate an audience's strategic blurring of the already tenuous distinction between the heterosexual mainstream and the gay margins of American popular culture. Library Journal DeAngelis (Sch. for New Learning, DePaul Univ.) examines three prominent "crossovers" within the context of queer theory, gay male audience studies, and "star studies" to understand the appeal of some performers to both gay and straight audiences. Exploring spectator/character dynamics in cinema, particularly in melodrama, DeAngelis probes the connections between identification and desire. He shows how studio publicity, fan web sites, and "dish" columns reflect changing attitudes toward gay icons, from Dean's "in and out" sexuality to Gibson's heterosexuality to Reeves's "panaccessibility." Although DeAngelis focuses on these three stars, the wider implications of his arguments merit consideration in a larger context. DeAngelis's prose occasionally bogs down in academic jargon, but mostly his argument is clear and concise, leaving room for continuing debate on audience response, criticism, and popular films. Highly recommended for film studies on gay-audience response, along with Alex Doty's Flaming Classics (LJ 5/00) and Steven Cohan's Masked Men (Indiana Univ., 1997). Anthony J. Adam, Prairie View A&M Univ. Lib., TX Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.

\ Chapter One\ \ \ James Dean and the\ Fantasy of Rebellion\ \ \ \ Four book-length biographies of James Dean were publishedin 1974 and 1975, along with a rash of articles commemoratingthe twentieth anniversary of the star's death. By this time, thelife story of the deceased star had already been extensively recirculatedin various other forms: "one-shot" publications, series of articles inpopular fan magazines, exposés in scandal magazines, biopics, and atleast two other book-length biographical studies. What is particularlydistinctive about this mid-1970s work is that it centered on the matterof how to determine the "truth" of the star's sexuality. Grappling with"evidence" that ranged from Dean's sexual involvement with a notednetwork television producer to his reputed appearance in a porno filmto the pleasure of having cigarettes extinguished on his flesh in S&Mbars, the 1970s biographers repeatedly asked: Was James Dean gay?\ Their answers conflicted. Conceding that Dean had had sex withgay men, some argued that he did so only for survival early in hiscareer; others posited that the star's acts marked him as bisexual. Athird group asserted that Dean was incontestably and exclusively gay.A salient feature of this debate was the extent to which evidence of thestar's homosexual acts necessarily constituted a homosexual identity.The debate took place in the first public forum about male sexualityin a Hollywood star in which the voices of self-identified gay men (aswell as men who openly acknowledged that they hadengaged in homosexualacts, but refrained from identifying themselves as gay) providedthemselves with an opportunity to speak and be heard.\ Conducted approximately five years after the Stonewall incident in1969, this public negotiation of a deceased star's sexuality drew itsrhetoric from a gay liberation movement in which, as John d'Emiliosuggests, "coming out" had begun to be considered as an act of personalaffirmation as well as political responsibility. The emergenceof the "homosexual Dean" thus coincided historically with the publicemergence of a subculture that had become eminently more visibleand vocal by the mid-1970s than it had been twenty years earlier duringDean's brief career as a film actor. Yet the potential for gay malespectators to affiliate this star with homosexual practice or identityhad existed since the mid-1950s. The fact that such an affiliation wasnot widely documented in the 1950s, but became prevalent by the1970s attests to a set of shifting power relations in the public discourseof homosexuality during this span of more than twenty years.In examining the historical reception of a popular male actor workingin the Hollywood studio system, the power relations of homosexualdiscourse are inextricably linked to another shifting set of differentialpower relations in star discourse. In this set of relations, the waysthat audiences receive, interpret, and appropriate the sexuality of starimages—in narrative and non-narrative forms—involves the ways inwhich various agencies authorize the representation of sexuality.\ The present chapter elucidates the ways in which social, legal, andpolitical agencies regulated the discourse of homosexuality in the1950s, the Hollywood film industry's response to this system of regulation,and the strategies that gay men used to intervene in the constructionsof personal, social, and sexual identity that were imposedon them. By relating the extratextual discourse of rebellion to the fantasyoperations that became accessible to gay men in their relationsto Hollywood stars, and evaluating James Dean's three primary filmroles in terms of these fantasy operations, I show how queer readingsof Dean emerge as imaginable reception strategies as early as the1950s, while the star persona continued to resonate as an accessible andhighly popular figure for self-defined heterosexual audiences. Chapter2 then proceeds to examine the development of these receptionstrategies over time, tracing the complex historical emergence of thehomosexual Dean.\ \ \ In a 1957 article for New Republic, Sam Astrachan analyzes the appeal oftwo of the most prominent members of "The New Lost Generation,"Marlon Brando and James Dean. Whereas Astrachan reveals a certainscorn and disdain for the aimlessness of both figures, he concedes thathe is willing to "sympathize" with Brando, because of both the actor'sconsiderable talents and the moral capacities he demonstrates throughhis character portrayals. In reference to Brando's role of the alienated,leather-clad, motorcycle gang leader in The Wild One (1954), the authorobserves that "there is a right and a wrong, and it is only whenBrando sees that he has been wrong that there is any hope for him."The widespread appeal of Dean's onscreen and offscreen personas ismore disconcerting for Astrachan: "In each of the Dean roles, the distinguishingelements are the absence of his knowing who he is, andwhat is right and wrong. Dean is always mixed-up and it is this that hasmade him so susceptible to teen-age adulation.... In James Dean, hismovie roles, his life and death, there is a general lack of identity."\ The observation that Dean embodies the alienated rebel hero withwhom confused adolescents could readily identify is typical of criticalevaluations of his persona in the mid-1950s. The more curiousand unique aspect of Astrachan's analysis occurs later in the article,when he suggests that Dean's directionlessness is symptomatic of alarger trend of alienated figures in contemporary fiction who demonstratea similar lack of personal or social commitment. Citing the recentexamples of Saul Bellow's Seize the Day, Herbert Gold's The ManWho Was Not With It, and James Baldwin's Giovanni's Room, Astrachanobserves that "without any change in expression, James Dean couldhave played Gold's carnival peace-time enlistee, and Baldwin's quasi-homosexual(we will leave Bellow's Tommy Wilhelm for the moremature talents of Marlon Brando).... The lack of identity that existsin James Dean also exists in the characters of these three authors. Baldwin,unable to finally commit his character to homosexuality, leaveshim on a foreign shore unsure even of his sexual nature" (17). Theactor's ability to portray these roles convincingly is thus figured notas a sign of the range of his acting talents, but rather as evidence of ahomology between Dean the biographical figure and the characters ofthe novels: in both cases, there is a troubling indeterminacy of characterand the lack of a core identity. Moreover, committing oneselfto a distinctive social and sexual identity becomes a personal and socialresponsibility well within the range of Dean's capacities, and thesocial malaise that Astrachan attempts to derive from the case studystems from the star's active refusal to assume this responsibility—a refusalthat the author perceives as all too convenient and prevalent incontemporary culture.\ Certainly, Astrachan's comments here fall short of suggesting or attemptingto confirm James Dean's homosexual tendencies. Such overtdeliberations of the star's sexuality would not be conducted for severalyears after his death. Astrachan's comments are nonetheless revealingsince they show that even in the years shortly after Dean's death,his star persona already harbors an indeterminacy that extends to therealm of sexual orientation. Astrachan also establishes a connectionbetween social and cultural discourses regarding two prominent social"problems" of the 1950s—homosexuality and the alienation andrebellion of youth, configured as "juvenile delinquency"—through recourseto the concept of identity. This connection becomes crucial inthe representation of the star's sexuality, in light of contemporary discoursesof rebellion and delinquency informing each of Dean's threemajor film roles, most evidently in Rebel Without a Cause (1955), butalso in East of Eden (1955) and Giant (1956).\ \ \ Homosexuality and Juvenile Delinquency\ \ \ Although many of the 1970s biographers considered it incontestableand self-evident that James Dean was homosexual, it is difficult to finddocumented evidence of the star's homosexual orientation in texts ofthe 1950s, and even more difficult to locate evidence that men who perceivedthemselves as homosexual in the 1950s also perceived Dean ashomosexual. This difficulty does not, however, suggest that the conjecturesand assertions of the 1970s biographers were ill-founded orfabricated, nor does the lack of evidence of Dean's historical receptionas gay in the 1950s prove conclusively that spectators at this timedid not perceive him as gay. Rather, these difficulties point to significantdifferences in the discursive tools available in American culturein two distinct historical periods—tools that impose limitations uponhow a historically specific culture imagines itself, and how individualsare invited to imagine and define themselves within that culture. AsJanet Staiger suggests, these limitations manifest themselves as powerstruggles, cultural contestations over the meaning of the "sign" ofhomosexuality, how this sign may be circulated in public discourse,and who may appropriate this sign for what purposes.\ An examination of the public circulation of the sign of homosexualityin the 1950s demonstrates the workings of this struggle and identifiesthe agents who assumed the power to regulate how homosexualitycould be imagined by individuals in culture. To a significant extent, itreveals a consensus perspective of homosexuality as a pathology thatposed a threat to the integrity of the nuclear family as well as the nationas a whole. At the same time, however, the examination demonstratesone manifestation of Foucault's assertion that, in discursive operations,"where there is power, there is resistance, and yet, or rather consequently,this resistance is never in a position of exteriority in relationto power." In the context of the 1950s, this resistance stems from acurious overlapping of discourses: homosexuality shared common discursivefeatures with juvenile delinquency, a social problem that arosefrom public concern over the presence of a teen culture that had beenemerging since World War II. While the dominant ideology used thisdiscursive similarity in an effort to contain the proliferation of bothsocial problems, the overlapping of discourses also provided seeminglydisempowered homosexuals with the means to imagine themselves andto construct their own identities in nonpathological terms. They did soby adopting and appropriating a term that was widely used to describethe activity of juvenile delinquents, "rebellion," and adapting this termto the particular circumstances of their own social oppression.\ The emergence of homosexuality and juvenile delinquency asprominent issues in the 1950s can be traced to social and culturalchanges brought about by World War II. Psychiatric explanations ofhomosexuality had been prevalent in the United States since the1920s, as Freudian psychoanalytic discourse progressively infiltratedmainstream American culture. In the war years, however, the militaryactively sought to detect aberrant and deviant behavior throughscreening procedures for inductees. At the same time, the enforcedisolation and segregation of the population by gender "created substantiallynew erotic opportunities that promoted the articulation ofa gay identity and the rapid growth of a gay subculture." Releasedin 1948, Alfred Kinsey's Sexual Behavior in the Human Male also profoundlyaffected subsequent efforts of gay subcultural communities tobe socially recognized and tolerated. On the basis of interviews conductedwith thousands of Americans of varying socioeconomic status,age, vocation, and religious affiliation, the report concluded that oneof eight American males had experienced sustained homosexual erotictendencies for at least three years, and among males he "found that 50percent admitted erotic responses to their own sex." Likewise, Kinseyfound that many individuals with past homosexual experiences laterled exclusively heterosexual lifestyles; thus, homosexuality became notonly a more common phenomenon but also a fluid rather than a stableidentity. The report both confounded and exacerbated attempts to appealto medical discourse in defining the homosexual as pathological,especially since it suggested that homosexuality was undetectable byhuman physiognomy. Paradoxically, as Robert Corber suggests, conservativeideologies had substantial interests in restabilizing homosexualityas a category of identity, and by continuing to maintain thathomosexuality was an identifiable psychological aberrance, the rootof the "problem" continued to be the individual who failed to adjustto sexual norms, and not the culture or society who oppressed theindividual.\ These conservative efforts justified the State Department's actionsin 1950 when it declared that homosexuals were unsuitable for governmentemployment because of potential susceptibility to blackmailthreats. Investigations resulted in hundreds of suspected homosexualslosing their jobs. Moreover, in the context of the Cold War hysteria ofthe late 1940s and 1950s, the homosexual was determined to be furtherunfit for government service not just because of his lack of emotionalstability, but also because his behavior revealed a weakness of characterat a time when it was deemed crucial to maintain a "moral fiber" strongenough to ward off corrupting external political influences. The inherentproblem of developing a reliable method for detecting homosexualitywas resolved by a curious displacement of personal onto politicalbehavior: "If an individual's sexual orientation could no longer bedetermined by her/his lack of conformity to the norms of male andfemale behavior, then it could be by her/his politics." The homosexualwas conveniently labeled as dangerous in the face of communism,desperate as he was to conceal a sexual identity that carried withit a damaging social stigma and an inherent weakness of character.\ As is the case with homosexuality, increased national attention tothe problem of juvenile delinquency is traceable to the war experience.If enforced gender segregation of adult men and women fosteredthe establishment of homosexual communities during the war, it alsoresulted in more adolescents entering the workforce while attendinghigh school. As James Gilbert suggests, this phenomenon initiated atrend of "adolescent consumerism" in which teenagers began to constitutea targetable market sector for the advertising industry. Prematureconsumers also threatened the structure of the nuclear familybecause of their emerging financial independence from their parents.From the late 1940s through the 1950s, rising discretionary incomeamong adolescents helped to generate teenage subcultures shaped accordingto discrete gender divisions: hot rods for boys, and teen magazinesfor girls.\ If the crisis over homosexuality in the late 1940s in large part resultedfrom a report that made homosexual behavior and identitymore opaque (and thus more threatening), the increase in juveniledelinquency was ostensibly easier to detect through crime statistics.The delinquency phenomenon also resulted in increased governmentjobs, through the formation in 1947 of two governmental committeesassembled to manage and contain the problem: the ContinuingCommittee on the Prevention and Control of Delinquency (CCPCD),which stressed the importance of action at the local level; and the Children'sBureau, which relied on the testimony of "experts" and centeredon social work services. Both new committees spurred nationalattention to the issue. Gilbert explains that while statistical reportsfailed to establish sufficient reliability to indicate a progressive increasein delinquency in the postwar period, what certainly did increaseboth through the trend of quantification and the committeeactivities was the degree of discourse surrounding the problem. Thisincrease resulted in new classifications of adolescent behavior by experts,redefinitions of juvenile delinquency, attempts to contain andredirect youthful energy toward more productive activities, and anxietyregarding the inability to isolate causes or effects of the problem.\ In the 1950s, then, the problem of isolating, containing, and definingthe still ambiguous categories of homosexuality and juvenile delinquencyresulted in more widespread concern over the proliferation ofboth phenomena, and the dispersal of descriptions within each of thesecategories parallels the fear that the phenomena would themselvesproliferate among individuals. Pathological discourse thus became anappropriate vehicle for the expression of this proliferation, and bothhomosexuality and juvenile delinquency were described through metaphorsof infection and contagion—metaphors that were used similarlyto incite public concern over the spreading of the communist menace.The Kinsey Report induced paranoia by demonstrating the ubiquity ofthe homosexual: if anyone in the crowd could now be gay (or might becomegay later in life), then it followed that homosexuality might proliferateby recruitment: "Homosexuality became an epidemic infectingthe nation, actively spread by communists to sap the strength of thenext generation." The Senate Committee on Expenditures in ExecutiveDepartments warned that "these perverts will frequently attemptto entice normal individuals to engage in perverted practices. This isparticularly true in the case of young and impressionable people whomight come under the influence of a pervert.... One homosexualcan pollute a Government office." In the discourse of juvenile delinquency,"the predominant metaphor was one of contagion, contamination,and infection," similar to descriptions of other phenomena inthe 1950s that were characterized by an "invasion from the outside."National attention was focused on the potential corruptibility of impressionableadolescents, whose sense of morality was still under development,and who were thus thought to be more susceptible to suggestionand conversion.\ If uncertainties regarding the indeterminate causes and effects ofhomosexuality and juvenile delinquency resulted in descriptions of thephenomena as diseases propagated by communism, the public concernover matters of causality also located the domestic environmentas the origin of a cure for both problems. According to Elaine TylerMay, "Many contemporaries believed that the Russians could destroythe United States not only by atomic attack but through internal subversion.In either case, the nation had to be on moral alert ... [and]many postwar experts ... prescribed family stability as an antidoteto these related dangers." The stable family capable of providing ahaven and source of protection required the persistent moral influenceof both parents in the home, as well as a strict division of genderroles between parents. Both of these prerequisites to stability hadbeen threatened since the war years, when fathers were away overseaswhile mothers worked in factories and offices. The ideal parental rolemodels of the postwar era appeared to be the father who functionedas breadwinner and the mother who resumed her role as family caregiver.While the father's return to a position of control in the familywas a necessary demonstration of his own masculinity, a 1958 articlein Look warned that fathers who worked too much or too hard wouldnecessarily fail to provide their male children sufficient exposure tothe ideal male role model: "A boy growing up ... has little chance toobserve his father in strictly masculine pursuits." And the mother'sfailure to observe the distinction between giving too much and toolittle attention to her children could have disastrous consequences. AsMay explains, "Mothers who neglected their children bred criminals,mothers who overindulged their sons turned them into passive, weak,effeminite [sic] `perverts.' Sons bred in such homes, according to psychologistsand psychoanalysts, would find it difficult to form `normal'relationships with women." Clearly, the 1950s mother assumed themore crucial parental role for ensuring that the child would avoid thedeviant paths of juvenile delinquency or homosexuality. In the oftenblatantly mysogynist discourse of gender roles of husband and wife,the female was also held responsible for the pressures that her spousewas forced to endure in order to maintain an ideal masculinity associatedwith earning power and sexual potency.\ In the monogamous heterosexual relationship, both the male andfemale were expected to conform to their respective gender roles. Byemphasizing both the adult male's greater susceptibility to the demandsof his female partner and the son's dependence on his mother toensure stable masculinity, however, dominant cultural discourses empathizedmore strongly with the male's plight. Early marriage was arequirement for the proper containment and expression of the sexualimpulse, and the requisite demonstration of masculine maturity, accordingto Barbara Ehrenreich, was to marry by the average age oftwenty-three: "If adult masculinity was indistinguishable from thebreadwinner role, then it followed that the man who failed to achievethis role was either not fully adult or not fully masculine. In the schemaof male pathology developed by mid-century psychologists, immaturityshaded into infantilism, which was, in turn, a manifestation ofunnatural fixation on the mother, and the entire complex of symptomatologyreached its clinical climax in the diagnosis of homosexuality."Reinforcing the equation of maturity with an acceptance ofthe role of responsible husband, the fear of being tainted homosexualpresented the greatest incentive for husbands not to leave their wives:"Homosexuality ... was the ultimate escapism." Still, it remainedthe responsibility of the wife not to become so "dominating" or sexuallydemanding that the husband might find cause to consider such anescape.\ It is through a system of categorical oppositions and equationsthat juvenile delinquency was ultimately associated with homosexualityin the failed domestic environment. Males developed their maturitythrough the appropriate childrearing practices of their mothers,so that they could eventually integrate socially and assume their properroles in the domestic sphere as breadwinner husbands. Children whowere either overindulged or undersupervised by their mothers wouldfail to perform this requisite social integration. They might becomehomosexual, but even if they did not, they remained isolated and sociallyalienated figures, "loners" who rebelled against the commitmentsexpected of them. Even if they committed no crimes, their antisocialbehavior provided sufficient cause to label them delinquents,until they grew older and could assume other social stigmas.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ Excerpted from Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom by MICHAEL DeANGELIS. Copyright © 2001 by Duke University Press. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher. \ \ \ \ \ STEVEN SPIELBERG\ Master Storyteller\ \ \ By Tom Powers\ \ Lerner Publications Company\ Copyright © 1997 Lerner Publications Company.All rights reserved.\ TAILER

AcknowledgmentsixIntroduction1ONE James Dean and the Fantasy of Rebellion19TWO Stories without Endings: The Emergence of the"Authentic" James Dean71THREE Identity Transformations: Mel Gibson's Sexuality119FOUR Keanu Reeves and the Fantasy of Pansexuality179Afterword235Notes239Bibliography267Index281

\ Library JournalDeAngelis (Sch. for New Learning, DePaul Univ.) examines three prominent "crossovers" within the context of queer theory, gay male audience studies, and "star studies" to understand the appeal of some performers to both gay and straight audiences. Exploring spectator/character dynamics in cinema, particularly in melodrama, DeAngelis probes the connections between identification and desire. He shows how studio publicity, fan web sites, and "dish" columns reflect changing attitudes toward gay icons, from Dean's "in and out" sexuality to Gibson's heterosexuality to Reeves's "panaccessibility." Although DeAngelis focuses on these three stars, the wider implications of his arguments merit consideration in a larger context. DeAngelis's prose occasionally bogs down in academic jargon, but mostly his argument is clear and concise, leaving room for continuing debate on audience response, criticism, and popular films. Highly recommended for film studies on gay-audience response, along with Alex Doty's Flaming Classics (LJ 5/00) and Steven Cohan's Masked Men (Indiana Univ., 1997). Anthony J. Adam, Prairie View A&M Univ. Lib., TX Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyDeAngelis . . . explores how male film icons are both shaped by-and help shape-gay male styles and cultural representations . . . . The author is best on James Dean's career, charting how the actor's emotional openness and vulnerability often made him 'look' gay and how that image was exploited in his films (as in his highly erotic relationship with Sal Mineo in Rebel Without a Cause) . . . . DeAngelis's analysis of cultural trends in both gay male and mainstream culture is often provocative.\ \ \ South China Morning Post[A]n intriguing area [that] DeAngelis treats with lucidity and tact. . . . This is an area halfway between gossip and fantasy. 'Is he gay?' easily becomes 'How would it feel if he was gay, and . . .' Both the actuality and the dream are weighed up and chronicled in this excellent publication.--Bradley Winterton\ \ \ \ \ From the Publisher“An important contribution to star studies, one distinguished by the way that it convincingly brings together queer theory, cultural studies, and close textual analysis.”—Steven Cohan, author of Masked Men: Masculinity and the Movies in the Fifties\ “What is James Dean’s appeal for generations of queer men? How did Mel Gibson win, and then alienate, a gay audience? What is behind Keanu Reeves’s sexual ambiguity? You will discover the answers to these, and many other, provocative questions about male stars and their male fans in Michael DeAngelis’s sharply argued and wonderfully written Gay Fandom and Crossover Stardom.”—Alex Doty, author of Flaming Classics: Queering the Film Canon\ \ \