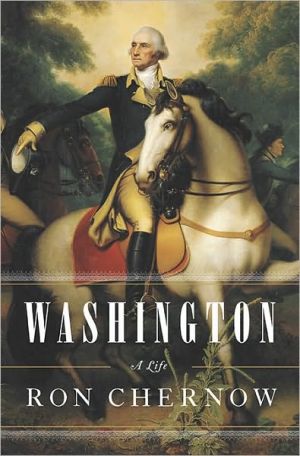

George Washington's America: A Biography Through His Maps

From his teens until his death, the maps George Washington drew and purchased were always central to his work. After his death, many of the most important maps he had acquired were bound into an atlas. The atlas remained in his family for almost a century before it was sold and eventually ended up at Yale University's Sterling Memorial Library.\ Inspired by these remarkable maps, historian Barnet Schecter has crafted a unique portrait of our first Founding Father, placing the reader at the...

Search in google:

From his teens until his death, the maps George Washington drew and purchased were always central to his work. After his death, many of the most important maps he had acquired were bound into an atlas. The atlas remained in his family for almost a century before it was sold and eventually ended up at Yale University's Sterling Memorial Library.Inspired by these remarkable maps, historian Barnet Schecter has crafted a unique portrait of our first Founding Father, placing the reader at the scenes of his early career as a surveyor, his dramatic exploits in the French and Indian War (his altercation with the French is credited as the war's spark), his struggles throughout the American Revolution as he outmaneuvered the far more powerful British army, his diplomacy as president, and his shaping of the new republic. Beautifully illustrated in color, with twenty-four of the full atlas maps, dozens more detail views from those maps, and numerous additional maps (some drawn by Washington himself), portraits, and other images—and produced in an elegant large format—George Washington's America allows readers to visualize history through Washington's eyes, and sheds fresh light on the man and his times. The New York Times - Virginia DeJohn Anderson Schecter…knows how to tell a good story in clear, vigorous prose.

George Washington's America\ A Biography Through His Maps \ \ By Barnet Schecter \ Walker and Company\ Copyright © 2010 Barnet Schecter\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-8027-1748-1 \ \ \ Chapter One\ VIRGINIA, BARBADOS, AND THE OHIO COUNTRY \ "I, reposing special trust and confidence in the ability, conduct, and fidelity of you ... George Washington, have appointed you my express messenger," wrote Governor Robert Dinwiddie of Virginia, on October 30, 1753. "I have received information of a body of French forces being assembled in a hostile manner on the River Ohio, intending by force of arms to erect certain forts on the said river, within this territory and contrary to the peace and dignity of our sovereign the King of Great Britain." Thus, twenty-one-year-old George Washington's military career was set in motion, with a commission from Dinwiddie and instructions to deliver the governor's letter to the French commanding officer, demanding the withdrawal of his forces from the Ohio country. This diplomatic exercise was also cover for a reconnaissance mission: Washington was to bring back not only a reply from the French, but intelligence on the size and disposition of French forces, their forts, and their lines of communication from Canada. (See A General Map of North America, page 20, and Detail #1, opposite.)\ Washington's mission in 1753, and his larger expedition to the frontier the following year, would stir up the smoldering territorial competition between France and Britain in the Ohio River Valley and help ignite a momentous contest for empire, the French and Indian War. For the first time a colonial war beginning in North America would spread to Europe—where it was called the Seven Years' War—and ultimately across the globe to Africa, India, and the Philippines. While victorious over the French and their Indian allies, the British would incur a staggering war debt, leading to efforts to tax the American colonies—and ultimately to the American Revolution.\ Governor Dinwiddie's selection of Washington for a critical and dangerous mission in October 1753 was the product of powerful family connections, combined with Washington's vigorous efforts on his own behalf. Having just secured appointment, with an aggressive letter-writing campaign, as one of Virginia's four adjutant generals, the hardy Major Washington had then volunteered for the five-hundred-mile journey to and from the frontier in the rain and snow of the oncoming winter. His physical strength, confidence, and ambition made his lack of diplomatic experience, or fluency in French, or even a proper British education, seem unimportant.\ Washington's half brothers, Lawrence and Augustine, were members of the Ohio Company of Virginia, a consortium of twenty wealthy planters speculating in land on the frontier, which had given Washington surveying work a few years earlier and had given Dinwiddie a share in the company, a welcome gift, considering his meager salary. (Technically, he was lieutenant governor; the absentee governor collected the large salary in England and paid Dinwiddie to do his job in America, a common arrangement in the British colonies.) The company welcomed the governor's attentiveness to its interests, which were now his own.\ After their father died in 1743, when George was eleven, Lawrence treated him like a son. Lawrence married Ann Fairfax, daughter of Colonel William Fairfax, of Belvoir on the Potomac. William was the agent for his cousin Thomas, Lord Fairfax, who owned the Northern Neck Proprietary, a vast grant from the Crown—roughly the size of Massachusetts—of all the land between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers from Chesapeake Bay to the crest of the Appalachian Mountains. From his youth, Washington was a frequent visitor at Belvoir with Lawrence, who had inherited the estate a few miles north, on Little Hunting Creek, which he named Mount Vernon, after Admiral Edward Vernon, his commander on the disastrous British expedition against the Spanish at Cartagena in 1741. (See A Map of the Most Inhabited Part of Virginia, pages 24-25, and Detail #1 and Detail #2.)\ Born on February 22, 1732, George Washington was the first of Augustine and Mary Washington's six children and grew up on Ferry Farm, across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg, Virginia. (His siblings were Betty, Samuel, John Augustine, Charles, and Mildred, who died in infancy.) George was a fourth-generation American, his paternal great-grandfather having emigrated from England and settled at Bridges Creek on the Potomac River (southeast of Fredericksburg and directly east of Port Royal). When Augustine died in 1743, he also owned a larger plantation at Pope's Creek, which included the Bridges Creek property, and which he willed to the second surviving son of his first marriage, George's half brother Augustine Washington. George ultimately inherited Ferry Farm, three lots in Fredericksburg, ten slaves, half of a tract of land on Deep Run Creek (the other half going to his brother Samuel), and a one-fifth share of his father's remaining property. George's mother was to live on the Deep Run tract, northwest of Fredericksburg. (See A Map of ... Virginia, Detail #1.)\ Washington was introduced to his first profession, and to the wilderness, at the age of sixteen, when he accompanied William Fairfax's son, twenty-four-year-old George Fairfax (another member of the Ohio Company), on a surveying trip for Lord Fairfax, which took them across the Blue Ridge to the Shenandoah Valley and beyond. Washington was undoubtedly impressed that two years earlier George Fairfax had helped survey the boundary line of the Northern Neck, and had proudly carved his initials in a tree at the source of the Potomac. (See A Map of ... Virginia, Detail #2, page 23.) The two Georges would remain friends for the next forty years. They set off from Belvoir on March 11, 1748. (See A Map of ... Virginia, Detail #3.) On the third day, as they rode westward toward Lord Fairfax's home, Washington began recording his love affair with the land. "We went through most beautiful groves of sugar trees and spent the best part of the day in admiring the trees and richness of the land," he wrote in his diary.\ Washington learned the trade of surveying: walking a tract of land, determining its boundary lines, and reading their bearings from the dial of a circumferentor, a magnetic compass mounted on a tripod. Two chainmen accompanied the surveyor and measured the boundaries using long chains, while a marker carved notches in trees to establish these lines. In his field notes, the surveyor recorded the boulders, trees, or other features that defined the corners of the tract, and he produced a plat, a small map that was part of the final survey document.\ Washington also got a taste of the rugged frontier conditions he would encounter in far greater doses in the future. After a night on a bed of straw full of lice and fleas, he resolved to sleep outdoors by the campfire. A night in Frederick Town on "a good feather bed with clean sheets" made him appreciate the comforts of civilization, while the journey built up his naturally strong constitution. They moved north to the Potomac and saw the "Famed Warm Springs" before crossing the swollen river in canoes while their horses swam. On the Maryland side they traveled "all the day in a continued rain to Colonel Cresap's right against the mouth of the South Branch." Thomas Cresap was a well-known frontiersman and one of the founders of the Ohio Company of Virginia. Their route, Washington complained, was "the worst road that ever was trod by man or beast." (See A Map of ... Virginia, Detail #4, page 29.)\ Some thirty Indian warriors arrived at Cresap's with a scalp and performed a sometimes "comical" war dance after the surveyors served them liquor. Washington was beginning to learn the customary ways of interacting with Indians—the gifts, liquor, and long speeches—that he would have to master in competing for their allegiance first against the French and twenty years later against the British. Moving west from Cresap's along the Potomac, the surveyors arrived at "the mouth of Paterson's Creek" before heading south to survey various lots all the way down to the Boundary Line of the Northern Neck. On March 31 Washington noted that he had surveyed a particular lot himself. The following night, Washington cheated death, as he would many times in his life, when the straw the men were sleeping on caught fire, and he was "luckily preserved by one of our men's waking" to warn the rest.\ Ten days later, Washington and Fairfax went hungry all day when their provisions ran out, and their supplier never arrived. It was a foretaste of one of Washington's greatest trials throughout his military career: struggling to feed his men in the face of countless logistical hurdles and disappointments with quartermasters. The next day the young surveyors headed home, traveling north and east for forty miles "over hills and mountains" to the Cacapon River and then to Frederick Town. They crossed the Blue Ridge at Williams Gap and stopped at West's Ordinary. The following day, after more than a month in the field, Washington wrote that "Mr. Fairfax got safe home and I myself safe to my brother's." (See A Map of ... Virginia, Detail #4, and Detail #3, page 27.)\ Apparently through the patronage of Lord Fairfax, and through William Fairfax, a member of the governor's council, Washington was appointed surveyor for Culpeper County (in the Northern Neck) the following year, at the age of seventeen. Surveying was a respectable profession, practiced largely by Virginia gentlemen, in which Washington could earn more cash income than most planters, while working only a few months a year. The work of surveyors in the rest of Virginia was confined to the counties to which they were appointed, but Lord Fairfax allowed surveyors in the Northern Neck to make surveys anywhere within the Proprietary. And since Culpeper County was already largely settled, Washington made only one survey there before heading across the Blue Ridge to the Shenandoah and Cacapon valleys in Frederick County, where droves of settlers and speculators were in need of his services, and where he could acquire tracts of frontier land for himself. (See A Map of ... Virginia, Detail #2, page 23.)\ When Lawrence was unable to shake off a persistent lung ailment, Washington accompanied him on repeated trips to the baths at Berkeley Springs in search of a cure. (See A Map of Virginia, Detail #4, upper right, labeled Medicinal Springs.) On these trips Washington was able to continue making surveys, including some for Lawrence, of land in the vicinity. "I hope that your cough is much mended since I saw you last," Washington wrote to Lawrence on May 5, 1749. "If so, likewise hope you have given over thoughts of leaving Virginia."\ But Lawrence evidently had tuberculosis, and his condition did not improve. That summer he went to England to see more doctors. Advised to seek a change of climate, Lawrence returned to Virginia and then traveled to Barbados in the fall of 1751. Despite the financial sacrifice entailed in putting his lucrative surveying career on hold, Washington did not hesitate to go as Lawrence's companion.\ On September 28, they embarked on a ship at the mouth of the Potomac, and spent more than a month at sea. Washington recorded his observations of the wind and weather and the ship's rigging in his diary, along with descriptions of the fish they caught for dinner. At last on November 2 came "the cry of land at four a.m.," Washington wrote. "We quitted our beds with surprise and found the land plainly appearing at about three leagues distance when by our reckonings we should have been nearly 150 leagues to the windward." Despite the captain's miscalculation of their course, by good fortune they did not bypass the island, which might have kept them at sea for another month. (See A General Map of North America, Detail #2, page 31.)\ They arrived in Bridgetown on November 3, and the following day had a visit from "an eminent physician" who assured Lawrence that his condition was curable and advised that he find lodging in the countryside, instead of in town. After leaving Bridgetown, Washington wrote rapturously in his diary about "the beautiful prospects which on every side presented to our view—the fields of cane, corn, fruit trees, etc. in a delightful green."\ Washington's attraction to military affairs—and an inclination to view topography in that light—was already evident in several diary entries. "Dined at the fort with some ladies," he wrote, and went on to describe the thirty-six cannon mounted in the interior and the two fascine batteries outside, making a total of fifty-one guns. Washington also noted that all around the island "large entrenchments have been cast up wherever it's possible for an enemy to land." The island's hilly terrain favored the defenders, combining with the trenches to make Barbados "one entire fortification." Washington noted that the island had mostly extremes of rich and poor, with virtually no middle class, a situation reinforced by the legal requirement that the rich provide for the maintenance of one militiaman for every ten acres they owned. This feudal arrangement meant that these dependent individuals "can't but be very poor," Washington concluded. The proper way to raise, train, and maintain the militia in America would become a central concern for Washington throughout his career.\ After making the social rounds of the island's gentry for two weeks, on November 17 Washington wrote that he "was strongly attacked with the small pox," which kept him confined for almost a month—but gave him immunity for the rest of his life. A week after he recovered, Washington began packing up to go home to Virginia, and on December 22 he bid farewell to Lawrence. Since Lawrence's condition was not improving, he was advised to proceed to Bermuda, where the climate might be even more conducive to his recovery. Washington was to bring Lawrence's wife to join him there, assuming that he was in better health.\ Washington again spent almost five weeks at sea on the return voyage, enduring the turbulence of stormy weather and "mountainous" seas. Finally, at sunrise on January 26, 1752, the ship sailed past Cape Henry, reaching the mouth of the York River that night, where it was met by a pilot boat. Arriving in Williamsburg for the first time, Washington called on Virginia governor Robert Dinwiddie and presented him with letters from Barbados. "He inquired kindly after the health of my brother and invited me to stay and dine," Washington noted. This first encounter boded well for their relationship—which two years later would put Washington at the flashpoint of Britain's territorial contest with the French in North America.\ Washington proceeded from Williamsburg to his half brother Augustine's home at Pope's Creek, before heading to Fredericksburg and then to Mount Vernon, where he delivered Lawrence's letters to his wife, Ann. Lawrence remained in Barbados for three more months and then moved on to Bermuda, but his health continued to decline. By June he was back at Mount Vernon, where he died on the 26th. On his deathbed he signed a release "in consideration of the natural love and affection which he hath and doth bear unto his loving brother George Washington," giving Washington unrestricted title to the three half-acre lots in Fredericksburg. Two years later, Washington would inherit Mount Vernon as well.\ Having inherited ten slaves from his father, Washington received eighteen with Mount Vernon and proceeded to buy and rent still more. Like most Virginia slaveholders, he kept them in abject poverty, housing, feeding, and clothing them as cheaply as possible. And for the next twenty years, until his convictions began to change, Washington showed no compunction about buying and selling slaves or inflicting harsh punishments. In at least one case he combined the two, shipping a slave named Tom off to the West Indies for sale as punishment for being "both a rogue and a runaway." He would fetch a good price, however, Washington told the ship's captain, since he was "exceedingly strong and healthy and good at the hoe." The captain should keep Tom handcuffed until they were at sea, Washington advised. Having calculated Tom's value in goods from the Islands, Washington asked for a hogshead of molasses, one of rum, a barrel of limes, a pot of tamarinds, two of "mixed sweetmeats," and the rest in "good old spirits."\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from George Washington's America by Barnet Schecter Copyright © 2010 by Barnet Schecter. Excerpted by permission of Walker and Company. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ Library JournalTo be clear, this coffee-table book is not a biography of George Washington; it's a study of the country as Washington came to know it, especially as indicated by the maps he collected and used over the course of his career. His personal collection of maps, including many he rendered himself, ended up in a one-of-a-kind atlas in Yale University's collections. The so-called Yale George Washington Atlas provides the bulk of the maps reproduced in this impressive volume. Schecter presents detailed map views of locations particularly germane to Washington's career and the growth of the country, masterfully aligning his historical account with applicable maps, giving readers the opportunity to study Washington's skill as a surveyor and cartographer in the process. The result is an impressive mix of history and geography, placing Washington's military and political career in geographical context. An appendix provides thumbnail images of every map included in the Yale atlas. VERDICT This lavish book, with its original approach and generous production values, is highly recommended as both a recreational and a reference work for specialists and informed lay readers of American geography, cartography, and Colonial through Federal-era history.—Douglas King, Univ. of South Carolina Lib., Columbia\ \ \ \ \ Virginia DeJohn AndersonSchecter…knows how to tell a good story in clear, vigorous prose.\ —The New York Times\ \