God's Sacred Tongue: Hebrew and the American Imagination

In a comprehensive examination of how Christian scholars in the United States received, interpreted, and understood Hebrew texts and the Jewish experience, Shalom Goldman explores Hebraism's relationship to American society. By linking history, theology, and literature from the colonial period through the twentieth century, Goldman illuminates the religious and cultural roots of American interest in the Middle East.\ God's Sacred Tongue is structured around a sequence of biographical and...

Search in google:

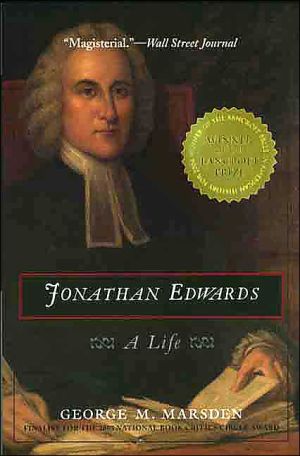

In a comprehensive examination of how Christian scholars in the United States received, interpreted, and understood Hebrew texts and the Jewish experience, Shalom Goldman explores Hebraism's relationship to American society. By linking history, theology, and literature from the colonial period through the twentieth century, Goldman illuminates the religious and cultural roots of American interest in the Middle East. God's Sacred Tongue is structured around a sequence of biographical and intellectual portraits of individuals including Jonathan Edwards, Isaac Nordheimer, Professor George Bush (an ancestor of President George W. Bush), and twentieth-century literary critic Edmund Wilson. Since the colonial period, America has been perceived as a western Promised Land with emotional, spiritual, and physical links to the Promised Land of biblical history. Goldman gives evidence from scholarship, diplomacy, journalism, the history of higher education, and the arts to show that this perception is linked to the role Hebrew and the Bible have played in American cultural history. The book's final section takes up the story of American Christian Zionism, among whose Protestant adherents political Zionism found much of its strongest support. Religious and cultural figures such as William Rainey Harper and Reinhold Niebuhr are among those who exemplify the centuries-old ties between America, the Land of Promise, and Israel, the Promised Land. Publishers Weekly Fascination with the Hebrew language has been a recurring motif in Christian America, and Emory University's Goldman surveys four centuries of American "Hebraists"-Protestant clergy and scholars who specialized in the Hebrew language and scriptures. He also provides nuanced portraits of a few Jewish scholars whose conversion to Christianity gained them access to, but never full acceptance among, university faculties in the 18th and 19th centuries. Among Goldman's recurring and disconcerting themes is how little the study of Hebrew did to prevent anti-Semitism from flourishing. Yet Goldman suggests that Hebraists also laid the groundwork for America's support of Zionism in the modern period-he devotes an intriguing chapter to the late-19th-century Hebraist George Bush, an ancestor of the American presidents of the same name. Unfortunately, this book hardly settles the question of how much difference the study of Hebrew has made in "the American imagination" at large. By focusing so narrowly on scholarly biographies, Goldman cannot avoid giving the impression that Hebraism was a distinctly rarefied field. In the hands of a more skilled storyteller, perhaps a clearer pattern would emerge, but Goldman's writing is prosaic and his narrative is somewhat stilted and sloppily edited-one quotation from John Adams appears, without elaboration, in three different places. Specialists will appreciate Goldman's historical spadework, but outside of the guild this book is likely to have a limited audience. (Mar. 29) Copyright 2003 Reed Business Information.

God's Sacred Tongue\ Hebrew and the American Imagination \ \ By Shalom Goldman \ The University of North Carolina Press\ Copyright © 2004 The University of North Carolina Press\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 0-8078-2835-1 \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ Lost Tribes and Found Peoples \ Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europeans understood exploration and discovery in the New World in biblical and Hebraic terms. This is, in effect, the earliest chapter in our history of American Hebraism, a Hebraism shaped within the context of the European history of ideas. For the Americas were thought to hold "Hebrew secrets." With the news of the European discoveries of the Americas, Christians and Jews sought ways to contextualize these astounding discoveries. Not surprisingly, a biblical worldview provided the context to explain the wonders of this New World. While Christians could accept that continents might remain unknown or forgotten for long periods of time, the enigma of unknown or forgotten peoples was more difficult to fathom. Had the Bible not accounted for the origin and spread of all of humankind? Genesis, Chapter 10, represents the three sons of Noah as the ancestors of all who live on the earth. For centuries the common Western understanding of the origins of the earth's diverse and far-flung peoples was that Europeans were descendants of Japeth, Africans descendants of Ham, and Middle Easterners the children of Shem or Sem. (Hence the designation "Semitic"-first applied to a group of Middle Eastern languages, later specifically to Jews). The peoples of the Far East were variously assigned to one of the three sons.\ But what of the peoples of the New World? To which son of Noah were they to be attributed? As historian of ideas Anthony Grafton noted: "The discovery of human beings in the Americas, after all, posed a hard question to scholars who believed that the world had a seamless and coherent history: where did they come from? Neither the Greeks, the Romans, nor the Jews had known of their existence. How, then, could Greco-Roman and Hebrew texts be complete and authoritative?"\ A ready-made solution to the enigma of the Native Americans was to link them to a people of biblical times who had long been lost to history: the "Ten Lost Tribes" of the Israelites. For many European scholars the biblical account was authoritative. Few disputed the accounts in the Book of Kings that chronicled the emergence of the Hebrew monarchies. In the tenth century B.C. the United Kingdom had divided into a Northern Kingdom, "Israel," made up of ten tribes, and a Southern Kingdom, "Judah," inhabited by the tribes of Judah and Benjamin. The biblical account of the fall of the Northern Kingdom of Israel in 722 B.C. concludes with this explanation of the fate of the kingdom's inhabitants: "In the ninth year of Hoshea the King of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away into Assyria, and settled them in Khalah and on the Khabur, a river of Gozan, and in the Cities of the Medes" (II Kings 17:6). The fate of these tribes would remain an unsolved mystery that would inspire fabulists and theorists from ancient times to the present.\ A century and a half after the fall of the Northern Kingdom of Israel, the Babylonian armies destroyed the Southern Kingdom. Jerusalem was laid waste in 586 B.C. The exile to Babylon-the paradigmatic exile of the Jewish experience-followed. The Jewish sense of self was forged in this experience. As the Psalmist wrote, "By the waters of Babylon we sat and wept as we remembered Zion." For the exiled Judeans, who yearned for Zion, there was no inclination to remember the ten tribes of the Northern Kingdom. The northern tribes were lost to history and to Jewish memory, their dispossession punishment for their sins of idolatry and wantonness. The Hebrew prophets spoke vaguely of a time when all the Tribes of Israel would be reunited; but this was in the End of Days. Ultimately, it was the fate of Judah that concerned the biblical narrator and later biblical commentators. Stories of the Lost Tribes only began to appeal to both Jewish and Christian audiences much later, during the medieval period.\ As Christianity made the Old Testament its own, fusing it with the emerging New Testament, the historical fate of the Lost Tribes was divorced from the issue of ethnic identification that Jewish writers and readers had brought to it. The Lost Tribes now became part of Christian history, and the stories found a new audience. History as told in the Hebrew Bible now served as a "universal history." Even before the advent of Christianity, the Hebrew Bible, in Greek translation, had circulated throughout the Greek-speaking world. Greco-Roman and early Christian cultures developed an interest in the fate of the "lost" Israelites. Perhaps these lost peoples were living among them? Perhaps they peopled distant and inaccessible lands? Perhaps some Christians were themselves descended from the lost tribes? For Christians this curiosity would serve to link them to Old Testament Israel in both the physical sense and the spiritual sense.\ With the spread of Christianity, speculation about the fate of these tribes became widespread. For many, Old Testament narrative was not only a moral teaching, but also a narrative of sacred history. While Catholic thinkers emphasized the allegorical in biblical history, the Reformation-with its focus on sola scriptura, scripture alone, as the key to truth-looked afresh at that history. In a book on the Lost Tribes one scholar noted, "No other subject seems to have had such fascination for the fanciful theorist." Such theorizing began in earnest with the publication of reports of the European discoveries. While a variety of theories emerged, the "biblical origins" theory was the most popular. As Grafton points out, "In 1614 Sir Walter Raleigh's magnificent History of the World still dealt at length with exactly the same enterprise, that of tying the Indians to the biblical history of man."\ The Jewish-Indian Theory\ For more than three centuries Americans have been fascinated with the attempt to "tie the Indians to the biblical history of man." Most of the adventurer-scholars portrayed in this book were engaged with proving, refuting, or reflecting upon this "biblical origins theory." Writing in the 1980s, intellectual historian Richard Popkin dubbed this notion "the Jewish-Indian theory." An American scholar of an earlier generation, Allen Godbey, compiled and analyzed many of the legends concerning the "true fate" of the Ten Lost Tribes of Ancient Israel. While Godbey's 1934 book focuses on the proliferation and acceptance of Lost Tribe theories, I treat those theories as part of the history of Christian Hebraism, the study of Hebrew and the Bible by premodern Christian scholars.\ One of the more remarkable episodes in the history of speculation on the fate of the Lost Tribes occurred in seventeenth-century Holland. In 1644 Antonio Montezinos, a Spanish explorer of Jewish ancestry (he was also known as Aaron Levi), returned to Amsterdam from an extended journey in the interior of what is now Eastern Colombia. Testifying in front of Amsterdam's Rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel, Montezinos stated that he had met on his travels "the remnant of the Tribe of Reuben." A group of Indians in the mountains of the New World had spoken to him in an archaic Hebrew. As Montezinos put it, "They greeted me with the Shema Yisrael." The report that these people knew the words of the Jewish creed, words as old as the Book of Deuteronomy, convinced many who heard Montezinos's account that this tribe was Israelite in some form. A close look at Montezinos's account reveals that he implied only that some lost Jews lived among the Indians, not that all of the local Indians were Jews.\ The news of this report spread quickly through European Jewish and Christian communities. The notion that the lost tribes had been "found" had a profound impact on millennialist thinking and politics in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. For many Christians and Jews, finding the remnants of the Lost Tribes served as a sign that the end of time was approaching. From this point forward the ingathering of the exiles and their return to the Land of Israel became an integral part of both Jewish and Christian millennialist thought.\ The Jewish-Indian theory, though today associated with fringe groups, "catastrophists," and other practitioners of wild historical speculation, was once accepted by some of the most respected and authoritative members of English and American society. Like Christian Hebraism with which it is sometimes conflated, this theory had little or no relationship to the Jews of its time. The Ancient Israelites generally-and the Ten Northern Tribes more specifically-were the object of inventive speculation. But Christians speculated only about their fate, not the fate of the Jews. The history of the Southern Kingdom, the group from which the Jews had descended, was well known: the exile to Babylon in the sixth century B.C., the Return to Zion "seventy years" later, the Second Temple and the reestablishment of the Jewish commonwealth, and, finally, the destruction of Judea-and Jerusalem, its political and spiritual center-by the Romans in the first century A.D. From this Judean culture, both rabbinic Judaism and Christianity emerged. The meaning of Jewish history was, therefore, clear to Christians (and to Jews, in a different sense). But what of the meaning and the fate of the Ten Lost Tribes?\ As so much of God's Sacred Tongue is devoted to writers who were engaged with this theory, we might ask what part did the study of Hebrew language and texts play in this heady mixture of scientific and theological speculation? Montezinos based his claims on the Columbian tribe's knowledge of Hebrew. Rabbi Joseph Hakohen had made a parallel suggestion earlier in his Hebrew-language Universal History of the Franks and the Ottomans. According to Rabbi Hakohen, the European discoverers of the New World found that "the Indians of the Americas were able to speak a little of the language of Ishmael." This story, which indicates that some Jewish scholars were interested in biblical explanations of New World discoveries, may have resulted from reports that Columbus's navigators attempted to speak Arabic to the Indians. To some readers it suggested much more: a "Semitic" origin for the American tribes. Christian and Jewish readers associated Arabic with its Middle Eastern origins. For Middle Eastern Jewish scholars Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic were languages that all exegetes and legalists had to know. Perhaps the American tribes, with their seemingly familiar language, were, in fact, of the children of Ishmael.\ That Columbus's navigators had a biblical orientation is not at all surprising, for Columbus himself was deeply imbued with a biblical worldview. Biblical passages, among them the accounts of King Solomon's voyages to Ophir, were among the ancient writings that convinced Columbus that he could reach Asia by sailing to the west. As the classicist James Romm noted, "Columbus saw himself taking part in a grand reenactment of a glorious moment in the biblical past; and such returns to early mythic patterns confirmed his belief that the ancient prophecies were being fulfilled and that history was at last reaching its end."\ In the realm of the history of ideas, Rabbi Menasseh's Hope of Israel proved the most important expression of the theory. Menasseh had heard Montezinos's testimony as to Israelites in America in 1644. In the late 1640s he wrote an essay on the larger issue of the Jewish role in history. Published in 1650 in Spanish, it soon appeared in Latin, Hebrew, English, and Dutch. "The English translation, Hope of Israel, excited minds on both sides of the Atlantic, with its most enduring legacy being its influence on early American ethnography and eschatology.... Not surprisingly, most readers saw what they wished to see in the Hope of Israel, rather than what Menasseh intended. Hope of Israel was an important piece of Jewish messianism primarily because of the notoriety Gentiles gave it."\ For some Christian readers Hope of Israel affirmed their expectation of the promise of the conversion of the Jews to Christianity. The Protestant Reformation had subverted the allegorical reading of Israel's fate. "Particularly among some of Calvin's followers, prophecies and statements dealing with Israel and Zion came to be understood at face value. Thus, the apostle Paul's promise that one day 'all Israel shall be saved' was taken literally as referring to scattered Jews and the Lost Tribes." In Protestant America these promises would take on new meaning and force.\ American Puritans, followers of Calvin, had a special affinity for the biblical and Hebraic, and this affinity survived in American culture after the decline of Puritan doctrine and political power. Thus, a process begun in the Reformation in which the Jewish content of Christianity was rediscovered and reevaluated found its culmination and fulfillment in an American setting. If we think of the first four Christian centuries as a period when Christianity distanced itself from Judaic texts and concepts, we might think of the past four centuries as a time when some Christian churches rediscovered Hebraic and rabbinic categories of thought and action. These rediscoveries, which enabled the emergence of both Christian Hebraism and Christian Zionism, did not necessarily bring about or translate into sympathy for the Jews. As we shall see in the following chapters, an unsettling ambivalence characterized early American Protestant attitudes toward Jews. As with other components of the Christian Hebraic endeavor, this too had its roots and parallels in English thought.\ England, steeped in a biblical tradition that identified and correlated English history with Jewish history, was at the forefront of such speculation. As late as the mid-nineteenth century influential British aristocrats were influenced by such speculation and adopted a "British Israelite" ideology. Fanciful philology backed up their claims that the Anglo-Saxons were, in fact, the descendants of Israel. Was Brit-ish not a code for Hebrew "Brit," covenant, and "Ish," man? Thus, the English upper classes were the true children of the Old Testament covenant. Though this group later discredited itself with its reactionary politics and thinly veiled anti-Semitism, certain of its ideas still persist in the upper reaches of British society. For its outlandish idea rested on a firm British foundation, the coronation of the British monarch is replete with Old Testament language and ceremony. In the 1953 coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, the Archbishop of Canterbury placed oil on the skin of the Queen as he recited this prayer: "And as Solomon was anointed King by Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet, so be thou anointed, blessed, and consecrated over the peoples, whom the Lord thy God hath given thee to rule and govern."\ \ Continues...\ \ \ \ Excerpted from God's Sacred Tongue by Shalom Goldman Copyright © 2004 by The University of North Carolina Press. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ From the Publisher"Fascinating study of the intellectual, religious, and political significance of the Hebrew language and culture in the United States. . . . Readable and well illustrated."\ — Furrow\ "The notes and bibliography, the readability and the subject of this work make it the best such narrative we have. . . . Likely to stimulate further work."\ — Religious Studies Review\ "Each chapter contains provocative stories of Christians in America who viewed the Hebrew language, and the Jews, either real or mythic, as well as the land of Israel, as utterly different than any other language, people or land."\ — American Historical Review\ "Meticulously researched, compelling, and often provocative." — American Literary History\ Often conceived of as out of the mainstream, Judaism has shaped the religious and intellectual culture of the United States. Shalom Goldman brings that insight to bear in his elegant narrative of key scholars and writers.(Bruce Chilton, Bard College)\ \ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyFascination with the Hebrew language has been a recurring motif in Christian America, and Emory University's Goldman surveys four centuries of American "Hebraists"-Protestant clergy and scholars who specialized in the Hebrew language and scriptures. He also provides nuanced portraits of a few Jewish scholars whose conversion to Christianity gained them access to, but never full acceptance among, university faculties in the 18th and 19th centuries. Among Goldman's recurring and disconcerting themes is how little the study of Hebrew did to prevent anti-Semitism from flourishing. Yet Goldman suggests that Hebraists also laid the groundwork for America's support of Zionism in the modern period-he devotes an intriguing chapter to the late-19th-century Hebraist George Bush, an ancestor of the American presidents of the same name. Unfortunately, this book hardly settles the question of how much difference the study of Hebrew has made in "the American imagination" at large. By focusing so narrowly on scholarly biographies, Goldman cannot avoid giving the impression that Hebraism was a distinctly rarefied field. In the hands of a more skilled storyteller, perhaps a clearer pattern would emerge, but Goldman's writing is prosaic and his narrative is somewhat stilted and sloppily edited-one quotation from John Adams appears, without elaboration, in three different places. Specialists will appreciate Goldman's historical spadework, but outside of the guild this book is likely to have a limited audience. (Mar. 29) Copyright 2003 Reed Business Information.\ \