Grandmother's Secrets: The Ancient Rituals and Healing Power of Belly Dancing

Search in google:

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ In The Beginning Was a Child\ \ \ When I look back on my childhood, four characters catch my inner eye: my grandmother, my grandfather, and the two pillars of my childhood: Adiba and Amina.\ We lived in a large two-story house in Baghdad, near the river Tigris. On the ground floor, a large corridor opened into rooms on the right and left, where my parents, my great-uncle, and I had our bedrooms. A huge common room, two storage rooms for food and other mysterious things, a guest room, a laundry room, and the kitchen completed the ground floor. My grandparents slept on the first floor, where my aunt, her husband and daughter, as well as my younger uncle and Adiba, one of my grandmother's cousins, all had their bedrooms. The official reception rooms were entered from a separate outer staircase, and whenever the sexes needed to be apart, the corridor was divided by a partition. Our common room stood at the center, and could be accessed from all bedrooms.\ Amina, an old woman whom my grandmother had met by chance in a hospital as a girl, also lived with us. Amina had burned her face and her whole body with boiling water to the point of mutilation. Compassion drove my grandmother to bring her home and take care of her. Amina had no-one else in this world, so she just stayed with us. Such was the core of the family; in addition, our house was always busy with the comings and goings of close or distant relatives and many friends.\ I hardly remember talking with my grandmother. Yet whenever she spoke, her voice enfolded mewith authority. Her gaze was serious; her eyes did not miss a thing: she was a sharp observer from whom nothing could be concealed. Whatever the situation, she grasped it in seconds. She read people by their body language. When I was a child, I respected her immensely, and feared her a little too. Whenever she called for me, I knew she had some kind of test in mind.\ My grandfather, on the other hand, was the symbol of a great soul for me. His movements were those of a wise old panther. He was known throughout the region for his hospitality, and had reputedly been the best horserider of his time—no small feats in a society still influenced by the Bedouin tradition, despite today's sedentary lifestyle.\ Adiba was a small round woman. Her eyesight was poor and since she was too vain to wear glasses, she would just screw up her eyes, which lent her face an odd expression. Adiba took in the things of life through her gentle heart. Her innocence was catching and came close to wisdom; she understood the world of children better than that of adults. In her ample bosom were buried all the family secrets.\ Amina looked almost like some creature from another world. In her face, heavily disfigured by burns, shone two black dots barely recognizable as eyes. But woe betide anyone who paid no heed to those dots! If you took the time—and children know no time—to look into her eyes, a dark, endless ocean would open and take you into a world beyond the limits of humankind, into the elemental foam where pain and joy go hand in hand on a shore named being. Amina's body was so delicate it could barely carry those eyes. Wherever she sat, she would adapt her outer shape to her surroundings in such a way that one often missed her at first sight. Amina was the quietest being I have ever come across in my life, yet she carried in her the rhythm of the whole universe.\ \ \ The Ancestral Call\ \ \ My grandmother would often watch me from the bench where she rested, sitting cross-legged. She would sit there for hours without moving while everyone in the house came to her for advice or instructions. She was a proud woman in whom dwelled an invisible force.\ One day she called me. I came and saw a blackboard at her side.\ "Come, sit next to me. I'd like to teach you an ancient craft. Take this chalk in your hand." She inserted it between my thumb and index finger and went on. "Now draw a dot and concentrate all your energy into this one dot. It is the beginning and the end, the navel of the world."\ Time and again, I drew the dot, and time and again my grandmother told me to concentrate all my being into the dot. "Let it flow out of you, until you really know who is making this dot and nothing stands between you and the dot."\ I didn't quite understand what she meant, and always drawing this simple sign really went against the grain. Still, after a while, I began to notice how my hand seemed to draw of its own accord and to keep returning to the dot. My thoughts disappeared and all that remained was the dot. I have no idea how much time had elapsed when I heard my grandmother tell me to go. "And come back when I call you," she added.\ The following day, she called me again. "Fawzia, come!" She sat at her usual place with the board next to her.\ "Now draw the first letter of the Arabic alphabet, the alif, a vertical line; start from the top, keep your hand light and put all your inner strength into the downward movement. Let the line become as long as three dots lying above each other."\ Again, I took the chalk between thumb and forefinger, and I made an alif: \\.\ She explained that the alif is the first expression of the dot. It is unique among all the letters of the alphabet and contained in all of them. Trace it with reverence, she told me, for the alif is the dot's longing to show itself. It is through the dot's longing to grow beyond itself that the alif is born. Regardless of their multiple, outer shapes, all letters are the alif in their essence.\ How difficult it was for me to draw this simple letter! I drew it so often that in the end I could see alif in everything. Wherever I turned, it would appear. I felt my body straighten into a living alif. My arms, hands, back, legs, and feet all turned into alif. Like a matchstickman, I was down to essentials, clear and transparent.\ Another day came when my grandmother called me. She sat on a bench in the garden, one leg folded under her, the other resting on the ground.\ "Anchor your feet to the earth and balance your weight on both legs. Now shift your pelvis to the right and then to the left, as if you were drawing a shell. Every time you reach the furthest outward point, stop, balance back to your middle and then to the other side. Now come, make the same movement with the chalk on the board: ??. Does this shape remind you of something?"\ "It's the second letter of the alphabet, grandmother, but the dot underneath it is missing."\ "The dot is the beginning," she explained. "The dot begets all the other letters. The dot is below and the alif in between: ??. Together, they form the word ?? (father), one of the names of the Divine. When you whirl or when you circle your pelvis, you are drawing the dot, the origins. From this shape all other movements are born—they all stem from this dot, from the navel in your belly."\ I was excited to know that I carried inside me a source from which everything was born. Time and again, I watched the inward spiral of my navel with respect. Going around with all this power inside my belly made me feel secure and confident.\ \ \ Have No Fear, Sister\ \ \ I used to observe my grandmother Fawzia, this fascinating woman whose name is also mine. She strolled through our house and although she was small, whenever she appeared, she filled the room. Her head, held high, rested calmly on her shoulders and her stance was always open and confident. One day I confessed to her that I was afraid to get up at night and go to the toilet, because it was so dark and far away. So she told me about my aunts and how when they were little, they had to walk out of the house, into the night, all the way to a distant earth-closet.\ "During the day, try to find your way with your eyes closed, and you'll see that you don't need to be afraid at night. The difference between day and night is like the opening and the shutting of the eyes."\ She often told me about other girls or women, linking me time and again into the chain of women. I began to feel I belonged to an invisible sisterhood that transcended past and future into eternity.\ \ \ Seeing Feet\ \ \ Whenever I went down the stairs in our house I looked down to avoid falling. One day my grandmother was watching me.\ "Let your feet see for you," she told me. "They'll keep you from falling much better than your eyes! Feel with your toes until you find the edge and let your heels slide down the stair until they find the next one. Put yourself in your center, in the place below your navel, and keep your head high!"\ That was fun, and I spent days going up and down the stairs like a queen. This is how I realized, with time, that my feet were "seeing" better and better. I felt my soles become more aware, my feet more sensitive and sensual. I came to trust them more and more, and my balance eventually settled in the lower part of my body.\ \ \ Good Morning, Mystery\ \ \ Every morning, shortly after sunrise, a Bedouin woman came to our house. Gracefully balanced on her head was the basket full of buffalo cream (gemar) that we had for breakfast. Whenever I managed to get up in time, I ran to the front of our house to catch sight of her coming from afar. I was fascinated by the way in which she approached, all dressed in black, quiet and regal, her step steady and confident. I always wondered how it was that the basket never fell and seemed to fit her head like a hat. Once at the house, she removed the basket and greeted me. Together we went inside where my grandmother inspected the cream and decided how much we needed for that day. We drank tea while the Bedouin woman told us the latest news. Then she would get up and replace the basket on her head before leaving. My fascination with the way she carried her basket hadn't escaped my grandmother, yet she did not say a word.\ I decided to get to the bottom of this mystery. The next morning, I could hardly wait for the Bedouin woman to arrive. Again, her soft steps carried her down the street.\ Before we went into the house, I whispered, "Please, tell me the secret: How can you carry the basket on your head without using your hands?"\ She smiled, took the basket down and showed me a round mat made of cloth that I hadn't noticed before.\ "Here is the earth, then me, then the mat and then the sky."\ "So where is the secret?" I wanted to know.\ But she would say no more, so I could only continue to observe her and admire her skill. Only much later would I come to realize the value of what I had witnessed and understand what the secret was really about.\ \ \ The Tale of Giving And Taking\ \ \ When I was a little girl, I wore my hair long, after an old Bedouin tradition according to which the hair is the seat of the soul. Looking after one's hair was therefore of utmost importance; it was cut only if absolutely necessary.\ Every morning, two of my aunts combed my hair. I sat on a stool with one aunt on each side. They parted my hair and together they combed it. The whole episode was usually punctuated by much shouting on my part. Still, they never let it interrupt them and went on combing, unruffled, until my hair was neatly braided in two braids. I was then free to start the day.\ Back in the sixties, it was fashionable to weave into one's braids ribbons with two ornate gold drops. In my heart I longed to have some. One day, my grandmother surprised me with this very gift. I was over the moon. Bursting with pride, I finally wove into my hair the jewels I'd set my heart on. With every step, I could hear them gently jingle around my head and I felt as though I was the most beautiful creature ever to have walked the earth. Nobody could miss my happiness, and all around me rejoiced in it.\ Later that day, we were invited to the house of some people I didn't know. The women of our house put on their best clothes and jewelry, draped themselves in their abayas, and off we went. I wore my new golden dangles with pride. Upon arriving at our friends' house, we were greeted by a crowd of women and I followed my grandmother nobly into the house.\ A somewhat older girl came up to me and exclaimed, "What beautiful golden dangles you have!"\ Before I could utter a word, my grandmother turned to me and said, "Take them off and give them to her!"\ I couldn't believe what I'd just heard. I should part with those beloved golden dangles, the ones I'd just been given? That could not be! Anger and despair welled up in me, yet I had no choice but to remove the dangles from my hair, and hand them to the stranger. I had to summon all my strength to fight back the tears and keep myself from jumping at my grandmother's throat — or at the girl's. How could my grandmother be so mean, when she knew exactly how much I adored those golden dangles! I spent the rest of the visit in a black hole. While the women, including my grandmother of course, chatted gaily, I sat, silently buried in my sorrows.\ On the way home, at long last, my grandmother spoke to me.\ "Little Fawzia, only the rich can give, and every gift comes back multiplied."\ Opening her hand and extending her fingers, she said, "The giving is the mother of receiving," and closed her fingers into her palm. Although I was somewhat mollified by her words, I still felt empty inside.\ Fifteen years later, in Abu Dhabi, I was sitting at the back of an elegant limousine, next to a woman with whom I had been acquainted for only a few hours. She handed me a small leather pouch and said, "This was given to me for you."\ Surprised, I took the pouch. When I opened it, I could not believe what my eyes saw. Tears washed down my face as the old familiar golden dangles lay in my palm. They looked just like my memories. Grandmother, O Grandmother, how modest and rich you have made me feel! May God bless me with the heart never to forget that giving is the mother of receiving.\ I have kept the golden dangles to this very day and one day, a girl will come and I shall weave them into her hair, so that she may be linked to the long chain of life, the natural cycle of becoming and letting go.\ \ \ The Magic Kitchen\ \ \ There was a room in our house in Baghdad into which no man or child was allowed. This was a holy place for women: the kitchen. My grandmother reigned over her domain like a queen; all the other women did her bidding. When she was not there, I used the opportunity to sneak into this exciting world that was shrouded in mystery.\ It was dark in the kitchen; women sat on the floor, all busy. Their scrubbing, cutting, and plucking filled the space. I peered over their shoulders and they smiled at me without interrupting their chores. There was always a huge pot on the stove, steaming away. The air was ripe with the many smells of herbs and spices. Not a single candle, gas lamp or electric bulb in sight. Daylight filtered through an opening high up in the wall. Dimness compelled the women to summon all of their senses for their work. Darkness, damp noises, and the smells rising with the steam, all lent the kitchen an aura of mystery.\ At about noon, Amina would sit near the entrance, in semi-darkness. She seemed so frail, as if a gust of wind would knock her over. She was always the first to taste the food, and I was often called to take it to her and feed her.\ Flies constantly surrounded Amina; although there were hardly any flies to be seen anywhere else in the house, they sat all over her and buzzed around her incessantly. Amina seemed quite undisturbed and didn't even bother shooing them away. I saw her sitting there for hours with her companions. I always wondered where they came from and why they always stayed with her. When I tried to scare them away, Amina turned her soft, watery eyes to me and said, "Little Fawzia, let them be, they too are God's creatures."\ When my grandmother entered the kitchen, nearly swallowed up in the dimness and steam, she checked the women's work and issued various instructions. I would have liked to participate, but every time I asked she drove me away.\ "No, not you, not yet," she would say. "It's too dangerous for you!"\ This always sounded so serious that I could only obey. Once, I plucked up all my courage and asked why it was that I could not help.\ "This is the place where things change shape once their time has come. They take on a different form and fulfill the true purpose of their existence; this is why you are not yet allowed here: your time hasn't come."\ Again, I didn't really understand what she meant, but I accepted it and from that time on, I stayed away from the kitchen.\ \ \ In the Garden of Thoughts\ \ \ The kitchen's outer wall made part of the garden wall. That was where my grandmother sat. The garden itself was almost square; along the wall grew fruit trees, palm trees, and other trees unknown to me. Surrounded by rosebeds and edged with tiles, grass extended over the center of the garden like a green carpet.\ To me, this was my real world, a place that sheltered and nurtured my dreams and fantasies. My longing for infinity grew on this green, between these walls where all greed for material things went quiet. In this garden full of wonders, I was able to discover myself, through play, without any interference from the outside world. It gave me a feeling of utter and all-embracing protection. A sparsely clouded sky covered my garden with its soft blue veil. In one corner grew a giant tree, as tall as my most daring child's thoughts, where several flocks of birds lived twittering and chattering together. The loudest bird was always the cuckoo; to this day, his call takes me right back to my childhood.\ My grandmother watched over this garden that had been laid out by my grandfather. Everyday, he came to talk to his roses. He caressed their leaves, his touch infinitely tender and gentle. There was such grief, such longing in his gestures. He told me that whatever the garden gave me, I should pass on. And the garden gave me so much: all the small wonderful creatures that lived there, the bugs and the ants, the birds that flew around and sang, the scorpions that lived beneath the stones and the cats that crept around. They all showed me how true greatness is found in what is small. My sensitivity grew and I became aware of the tiny wishes that become woven into great thoughts.\ Behind the walls of our garden lay another garden which belonged to our neighbors, and beyond their walls lay yet another garden. The voices of playing children rose from each of these gardens, which seemed linked in an endless chain. I saw Baghdad as a city of children, a paradise made just for us. Whenever I wanted to see the other children, I'd climb on a ledge, stand on the tip of my toes and peep into the neighbors' garden. To me, this was more exciting than going there, for I could enjoy at one and the same time being alone and having company. What I really loved was being one with all creatures, visible and invisible. My world felt disturbed by outside visitors. And somehow, my intuition told me that this would be but a short, sheltered episode, after which I would soon be set loose into a loud world.\ \ \ The Other Garden\ \ \ One day, from one of the neighboring gardens, I heard loud shouts that seemed to come out of countless children's mouths. They were so loud and wild that, at first, I just didn't want to know what was going on. But all of a sudden, two pairs of dark eyes looked over the wall into my garden. I felt them instantly and looked back. The eyes belonged to a slightly older boy, maybe seven years old, and to a younger girl. They gestured to me invitingly. I approached cautiously.\ "Do you want to play with us? We're playing hopscotch."\ "Who's we?" I asked them.\ "All of us. Come on!"\ All of us—who was "all of us?" I decided to find out—and, in order to avoid any possible confrontation, I didn't ask for permission. So over the wall I climbed, assisted by both children, into the other garden. I was so busy getting myself on top of the wall that I only realized where I was once I found myself in the middle of it.\ This garden was indeed different from ours. It was long and didn't quite deserve the name of "garden": except for four huge trees which met at the top and cast shadows over the whole place, nothing grew there. The ground was well-trodden and hard as stone. A seemingly endless swarm of children suddenly stood in front of me and stared.\ "Who are you?" I asked, both proudly and fearfully.\ The seven-year-old boy in the front replied. "We moved into this empty house a fortnight ago. I'm Ahmad—what's your name?"\ "Fawzia." I was about to add half my genealogy but left it at that since he too had only revealed his first name.\ The children went back to their game, which involved hopping vigorously in a row of squares engraved on the ground, and then turning around and returning to the starting point. The idea was to jump over the sides of the squares without touching them. I watched for a while. I was barely interested in the game, but the children intrigued me. They were all barefoot and looked really raggedy and neglected. The younger ones had runny noses, which didn't seem to disturb them in the slightest; the older girls, six, maybe seven years old, carried toddlers on their hips and when their turn came to play, they put them on the floor The toddlers usually cried until someone picked them up again.\ "Come on, I'll show you where we live," Ahmad said to me.\ Wherever I went, the children would step aside and make way for me, respectfully if not fearfully. I was amazed and I wondered why so many children would shy away from just one child. Still, I was a guest after all and I satisfied myself with that explanation.\ We arrived at a mosaic-tiled inner yard surrounded by a two-story house. The air was so thick that it took me a while to catch my breath. It was like being inside a beehive. People poked out of every door, every window, every single gap: women carrying infants and toddlers in their arms or on their hips darted through the yard, hung washing, kneaded dough, washed rice, loudly shouting orders, reprimands, or greetings at each other.\ Ahmad looked at me and yelled over the din, "Come over to my mother!"\ We crossed the yard to a woman who sat on the floor kneading dough. Middle-aged, Oum Ahmad wore her shoulder-length hair bound in a small headscarf and looked exhausted, but friendly. When she saw us, she jumped to her feet, wiped her hands on her apron and bowed.\ "What an honor! Please come sit down!"\ Slightly confused, I answered, "The honor is all mine," and took a seat. Ahmad's mother was about to rush inside and demonstrate her hospitality, but I thanked her and begged her to sit down. I wanted to know how many families lived together.\ "There's a family in every room, which makes approximately sixty families. We moved in a fortnight ago because we heard that this house was empty and we'll be staying until they throw us out."\ My eyes turned to Oum Ahmad's proud belly.\ She laughed and said shyly, "I have seven children, praised be Allah! That's plenty, isn't it? I bet your mother doesn't have so many!"\ I gave no reply, because I didn't want to hurt her feelings. "No" would mean that my mother could never understand Oum Ahmad's difficult, chore-laden existence and "yes" would not reflect the truth. As I looked around, I saw girls of my age busy with household chores. They fetched wood for the stove, carried massive washing baskets, washed and scrubbed the floor, and seemed really distant from their childhood days. They seemed to relate to their mother as someone with whom they shared both their work and a common destiny; their attitude was brisk yet very intimate.\ All of a sudden, there was a big uproar in the garden and one of my grandmother's servants burst in.\ "Here you are, Fawzia. We've been looking for you all over the place! Your grandmother's mad at you!"\ I stood up at once and made to leave.\ "You'll come back, won't you?" asked Oum Ahmad.\ "I'll be back," I replied, as the servant shook his head.\ I was greeted with severe concern, but that was immaterial. I'd understood something, I'd got to know a new picture, I'd seen an above and a below and discovered a new garden.\ A violent discussion ensued between my mother and my grandmother, the first being in favor of my getting closer to and acquainted with this world, the latter all for separation. Yet I wasn't much affected by it all. Whether I went or not didn't matter as much as knowing that Ahmad and Oum Ahmad existed and that there would forever be a place for them in my heart.\ \ \ Grandfather, the Quiet Warrior\ \ \ My grandfather stood a head higher than everyone else, but his real greatness lay in his soul: he was a true warrior, proud, his heart humble and modest. He was our family's protector, its most gifted story-teller, its tireless provider of nourishment and prodigal generosity.\ After lunch every day, he lay down for a few hours while the temperature was at its highest. In true Arabic fashion, this afternoon rest lasted from two until five, and it was deemed most inconsiderate to disturb the afternoon peace by visits or anything else.\ During the afternoon, the world of fairy tales came alive. We lay down on mattresses on the floor and I sought the dark by putting my head between two mattresses. My grandfather's deep voice carried me into the mythical world of demons, djinn, and other wonderful creatures. He told me about proud, powerful women, about their strengths and all the difficulties they encountered and how they always found help through their courage, their faith, and their cunning. Those stories made me into a fighter and gave me the courage to choose and to ask. My grandfather did this in such a light and simple way that it was only much later that I realized the magnitude of his gift.\ Because of his unconventional vision of the world, some of my relatives thought of my grandfather as being rather strange. Yet this was precisely what drew me to him.\ "Stretch out your hands," he said to me. "Take a good look at them."\ I obeyed, eager to discover where he would lead me this time.\ "Now imagine your hands turning into a baby's, then into an old woman's, and then again into your hands as they are now."\ I held out my hands, one next to the other. I tried to follow his instructions, but nothing happened.\ "It's all the same, Jiddi," I told him.\ "And so it is. There's but a batting of the eyelid between an infant's and an old person's hand, my child." He smiled softly, brought a glass of water to his lips and drank with half-closed eyes. "Whenever you can't understand, little Fawzia, then just wait and let it be. You'll find out that the answer will grow in you, just like desert flowers do. They stay hidden beneath the sand for a long time, and when the rains come, they suddenly sprout and the whole landscape becomes filled with their blossoming pride. Everything grows effortlessly at the right time; one needs only pay attention and listen carefully to recognize this moment. For that you need faith."\ In the evenings, when the whole family gathered, my grandfather was the quiet center amid the loud and lively goings on. His usual dish of yoghurt with finely cut cucumber was placed on a low table in front of the sofa where he sat, totally relaxed. I always had the feeling that it was the dish of yoghurt that kept him from disappearing altogether; time and again, he reached for that dish that kept him attached to the material world. My grandfather's quiet, aloof, yet lovingly embracing way gave me the skill of observation. His presence alone sharpened my senses and made me open up so that I could take in as much as possible.\ (Continues...)

Forewordvii Part One: How It All Began In the Beginning Was a Child3 The Ancestral Call4 Have No Fear, Sister6 Seeing Feet7 Good Morning, Mystery7 The Tale of Giving and Taking8 The Magic Kitchen10 In the Garden of Thoughts11 The Other Garden12 Grandfather, the Quiet Warrior14 The Dancing Heart15 Oh, the Ball!17 A Women's World20 Blood Flows22 The Great Celebration24 My New World25 Part Two: A History of Women's Dancing Primitive Peoples and Dancing29 Dancing in the First Advanced Civilizations35 The Greeks36 The Romans38 Christianity39 The Middle Ages40 The Arab World42 The Bourgeoisie46 Industrial Times47 The Present Day49 Mother Belly53 In Praise of Dancing54 Belly Dancing58 The Basics of Belly Dancing61 Part Three: From Head to Toe Hold Your Head Like a Queen (The Head)68 The Ocean of the Soul (The Eyes)71 The Gateway to the Soul (The Ears)76 Fragrance, Take Me Back From Whence I Came! (The Nose)82 Serpents in the Wind (The Arms)89 Giving is the Source of Receiving (The Hands)93 The Breath of Divinity Lies in Your Breast (The Breast)96 Meekness Rests Proudly on Your Shoulders (The Shoulders)101 When Your Hips are Circling, the Whole Universe Swings Along (The Hips)104 The Snake of Spontaneity is Coiled in the Pelvis (The Pelvis)110 As Full as the Moon, as Soft as Clouds in the Wind (The Belly)114 The Pillars of the Temple (The Legs)118 Hold My Feet, Mother and Give Me Strength (The Feet)120 Part Four: Variations and Rituals The Floor Dance125 The Stick Dance128 The Veil Dance129 Walking and Whirling131 The Menstruation Dance (Rahil)139 The Wedding Dance141 The Birth Dance142 The Trance Dance147 The Mourning Dance149 Epilogue151 Works Cited155 Endnotes157

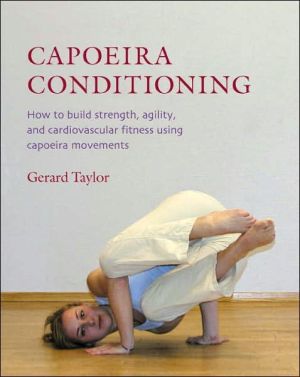

\ Karen WyckoffWith the descriptions of ritual dances that mark a woman's life...her birth, womanhood, seduction and mourning...this book unveils a commonality that transcends all cultures and offers hope. These woman pass their lives gently, each one as a single day in the greater, endless lifetime of a collective spirit, dancing to a rhythm nearly circadian in nature. \ —ForeWord\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalAfter recounting her own childhood and coming of age in the Arab world, Al-Rawi reviews the history of women's dancing and reflects on the individual movements used in this ancient art form. In a section titled "Variations and Rituals," she describes nine different dances (e.g., the Wedding Dance, the Birth Dance) and sets them in context. Photographs evoke the mood of each dance, suggesting a general impression rather than step-by-step instruction. The narrative, however, supplies enough detail that the interested reader may wish to try a dance. Throughout, Al-Rawi relates movement to ideas and art to philosophy so that, in her words, "belly dancing becomes a source of inspiration, a means of collecting and strengthening oneself, and a clear and dynamic way of discovering...and understanding oneself." An interesting glimpse into a culture, an art form, and a means for women's healing and self-expression; suitable for most circulating collections, especially those whose readers are interested in Arab culture, dance, and women's studies.--Carolyn M. Mulac, Chicago P.L. Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ BooknewsThe author blends personal memoir with an instructional guide to the dance known in the West as belly dancing. It is not only the story of a young Arab girl as she is initiated into womanhood, but a history of the dance from the earliest times to the present and a personal investigation into the effects of the dance's movements on individual parts of the body and the whole psyche. Originally published in German as Der Ruf der Grobmutter by Promedia (1996). Annotation c. by Book News, Inc., Portland, Or.\ \