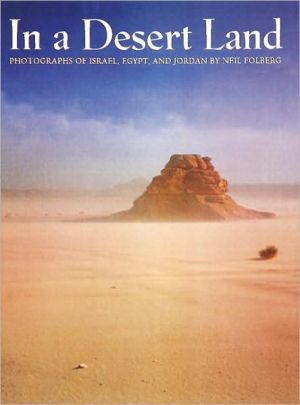

In a Desert Land: Photographs of Israel, Egypt, and Jordan

Neil Folberg's images of the wilderness of Israel, Egypt, and Jordan are as triumphant as Ansel Adam's depiction of the American West—with the added dimension of color.\ These places are among the most beautiful on earth—the deserts of the Middle East, the Dead Sea coast, the ancient splendor of Luxor, the pyramids at Giza, and the eternal presence of Jerusalem itself—and their beauty all the more intense because of their rich historical and religious association. Breathtaking folio-sized...

Search in google:

Neil Folberg's images of the wilderness of Israel, Egypt, and Jordan are as triumphant as Ansel Adam's depiction of the American West—with the added dimension of color. These places are among the most beautiful on earth—the deserts of the Middle East, the Dead Sea coast, the ancient splendor of Luxor, the pyramids at Giza, and the eternal presence of Jerusalem itself—and their beauty all the more intense because of their rich historical and religious association. Breathtaking folio-sized reproductions of large-format photographs capture sacred vistas, images of awe, serenity, and ravishing beauty: the Oasis of Ain Umm-Ahmed, the view from the summit of Mount Sinai, a Bedouin orchard in the midst of a desert wadi, the dusty life of village and town, the Temple Mount, and the Wailing Wall. Accompanying these photographs are Neil Folberg's delightful firsthand narratives recounting the humorous and harrowing adventures of a photographer in a politically troubled and naturally formidable land. While Folberg entreats only that you follow him into the landscape of his vision and derive pleasure wandering and wondering, the photographs of In a Desert Land—celebrations of beauty sacred and natural—are in fact moving prayers and persuasive arguments for sanity and peace in a reckless region and a volatile world. Other Details: 200 full-color illustrations 204 pages 9 x 9" Published 1998superficial unity among the photographs. When you set an ambitious goal, you risk failure. If you fail to set a worthy goal, you risk achieving only something small. I decided to climb a large mountain and set my sights on some distant goal. There was always the risk of falling or choosing the wrong path, but the unattractive alternative was to wander aimlessly through the desert, leaving all to chance, making photographs with no purpose. The yardstick against which I measured my success was experience. If my photography evoked something of the feeling of the place and created a sense of its proportion—usually vastness—while giving enough information about the landscape to make it seem real, and if, beyond this, the photograph was satisfying as a purely aesthetic object, then I had made a good photograph of Sinai. If not, not. Nothing less would do. So it was that I found myself, more and more, climbing mountains to get a higher vantage point. The trick was to find a point high enough to impart a sense of the environment without losing intimacy, the feeling of having my feet firmly planted on the ground. This didn't always require height, of course, but more a sense of scale, or balance. That's what John Gardner called it, "a proper balance of detail and generality, the particular and the universal." This is a fine line to tread. I had always to be aware of another danger, the pitfall of color, the merely picturesque, color without content. Indeed, I'd begun this project like all my preceding ones, in black and white. On my first trip with Aryeh Shimron, I brought both black and white and color materials. I processed only a few of the black and white images and threw the rest away without developing them. The reason was simple: the desert consists largely of monochromatic earth colors. These colors are subtle and beautiful, but they translate into black and white as various shades of middle gray. Filters and development controls would have helped create some contrast and interest, but these wouldn't have proved sufficient. I learned such techniques from the master, Ansel Adams, but I also learned from Ansel what it means to "pre-visualize," to decide in advance what statement you're making, how to see the subject, and how to create the final print in accordance with your vision. I didn't want shades of gray, middle or otherwise; I wanted color. I wanted everyone to see the loveliness of the delicate coloration and the way it changed so dramatically according to the season and the hour of the day. The same map will lead different people to different places. Odd that some find this fact so hard to accept. I am told that a museum curator visited an exhibition of mine and said, "If Francis Frith photographed that area in black and white, why does Neil Folberg need color?" One of the main reasons Frith photographed in black and white was that color photography had yet to be invented. In quest for more "scientific" accuracy Frith and many others of his period would almost surely have used and loved color. Many of us recall the days when "art films" were made exclusively in black and white, and only the slick commercial films in color. In the art world there is a certain snobbishness about black and white. This doesn't concern me; each medium has its uses. Nevertheless, there is a danger of mistaking color for content. It is an error I've certainly tried to avoid. There are those who say that the viewpoint of my photographs is distant. Quite right; but I hope it never seems detached, for my involvement with the subject is intimate. My viewpoint enables you to wander through the photograph as I have wandered through the landscape. You must be given the opportunity to choose your path as I have chosen mine. While walking through the desert, one thinks of many things. I present a setting and a mood (this generally having been determined by my mood when the photograph was made). I want you to use your imagination, to think your thoughts—in short, to wander and wonder. I don't care to confine you by imposing my convictions on you. Derive pleasure from being with me in the places I have been. As John Fowles wrote, "We...know that a genuinely created world must be independent of its creator; a planned world (a world that fully reveals its planning) is a dead world." "Folberg captures with his camera something that is beyond man's ability to create—the awe-inspiring configurations of nature, the sweeping vistas, the colors... Folberg's landscapes are fluid moments in time... Although one may never walk in these desert lands, one is drawn into the images as one is drawn to an altar—as a place to seek peace." —Artweek "The word for photographer in nineteenth-century Hebrew was tsayar shemesh, "painter of the sun." The Arabic expression mussawwra shamsi still has the same meaning. Neil Folberg has breathed new life into this old concept, that the sun does the painting. Looking at his brilliant landscapes, we imagine him sitting behind his camera, waiting for the sun to rise and color the sky purple, cast shadows upon the mountains, and make the sand dunes translucent. Then all Folberg has to do is release the shutter, capture the scene created by the sun, and transmit it to us." —Nitza Rosovsky, from "Neil Folberg in a Desert Land" Author Biography: Neil Folberg, born in San Francisco and raised in the Midwest, now lives in Jerusalem and can be found there at Vision Gallery. A student and colleague of the late Ansel Adams, Folberg has photographed extensively the landscape and architecture of the Mediterranean area. Folberg's most recent book is And I Shall Dwell Among Them (Aperture), winner of the 1996 National Jewish Book Award.Library JournalIn this large, heavy, and luxurious book of color photographs of the Near East, Folberg's focus is the natural beauty of the rugged landscape rather than political turmoil. The images, splendidly seen and reproduced, are grouped by regionEgypt, Sinai, Jordan, and Israelwith each group accompanied by an interesting narrative by the photographer. Annotations for the photographs, together with small black-and-white reproductions, occupy a 30-page addendum. Nitza Rosovsky, Harvard Semitic Museum curator, provides an illustrated essay on the history of photography of the area. A beautiful book worth having. Frank Davidoff, formerly Consultant, CBS Broadcast Group, New York

Introduction\ The heart of this book is in Sinai. I have traveled and photographed sporadically in the land of the Nile; in greater depth I've explored the wilderness and hills of Judea as they rise from the Dead Sea of the Jordan Rift toward Jerusalem. For the sake of geographic and visual continuity, I open the book with Egypt, passing through the desert landscapes finally to arrive at the ancient walled city that nestles in the hills at the edge of the Judean Desert—Jerusalem. This I am fortunate to call home, though I would call it that no matter where I lived.\ I began photographing Sinai in 1979. The land was addictive in its power to draw me. Only there could I experience the power of wilderness, of open spaces and desert mountains. Had I not been kicked out of Sinai by political circumstance, I would have continued working there, never thinking of anyplace else. With access to Sinai restricted, after Israel ceded the territory back to Egypt, I drew back to get a wider perspective. Sinai was, after all, in the heart of the Middle East, a bridge between continents, between the land of Egypt and the land of Israel. So the time had come to begin exploring and photographing in both of these directions as well.\ The challenge of landscape photography is to reduce a limitless expanse to the confines of a two-dimensional rectangle without creating a feeling of confinement within borders. It is necessary to give enough information about the environment so that the imagination can extrapolate beyond the edges of the photograph, to envision what might be beyond the next ridge, to create in the image before the viewer's eye a mood evocative enough to make him want to wander inhis mind through that image. This is the challenge of all landscape work, but Sinai is particularly difficult, for its true beauty is not immediately evident. The beauty of the desert lies less in its small delights—a wildflower, a pool of water—than in the delight of finding these things in the midst of dryness. Then there is the naked, treeless expanse itself, impressive precisely because of its vastness.\ So my first task was simply to be there, to look around, to get the feel of the place. This I was able to do through the kindness of Dr. Aryeh Shimron of the Israel Geological Survey. At that time, in 1979, he was making regular trips to Sinai, expeditions that usually consisted of two Jeeps, often with room in one of them for a guest. Needless to say, there were many eager to join these trips, but Aryeh felt that Sinai was something to be shared only with geologists. Accordingly, he made room for me, a photographer.\ We visited mostly the less obviously scenic areas in Sinai, areas of dark-red metamorphic rock and broad, nearly featureless wadis that sometimes go on for great distances. My recollections of these earliest trips are sparse, and most of the photographs I made were trivial. Even when there was something attractive in them, they neverless failed to evoke the feeling of the place. Each time I returned from Sinai and looked at my work, I knew there was something missing.\ By fortunate coincidence, I happened to read at about that time On Moral Fiction, a book by John Gardner. He wrote, "The lost artist is not hard to spot. Either he puts all his money on texture—stunning effects, faudulent and adventitious novelty, rant—or he puts all his money on some easily achieved or faked structure, some melodramatic opposition of bad and good which can by nature handle only trite ideas. One sort of artist can see only particular trees, the other only the vague blackish-green of the forest. The artist who gives all of his energy to texture... can say virtually nothing because his work consists wholly of nonessentials."\ Reading this confirmed my intuition that the photographs I was making, though occasionally intriguing, missed the mark. First of all, I needed to identify the essence of Sinai and work to capture it while avoiding any reliance on visual formula to create a superficial unity among the photographs. When you set an ambitious goal, you risk failure. If you fail to set a worthy goal, you risk achieving only something small. I decided to climb a large mountain and set my sights on some distant goal. There was always the risk of falling or choosing the wrong path, but the unattractive alternative was to wander aimlessly through the desert, leaving all to chance, making photographs with no purpose.\ The yardstick against which I measured my success was experience. If my photography evoked something of the feeling of the place and created a sense of its proportion—usually vastness—while giving enough information about the landscape to make it seem real, and if, beyond this, the photograph was satisfying as a purely aesthetic object, then I had made a good photograph of Sinai. If not, not. Nothing less would do.\ So it was that I found myself, more and more, climbing mountains to get a higher vantage point. The trick was to find a point high enough to impart a sense of the environment without losing intimacy, the feeling of having my feet firmly planted on the ground. This didn't always require height, of course, but more a sense of scale, or balance. That's what John Gardner called it, "a proper balance of detail and generality, the particular and the universal." This is a fine line to tread.\ I had always to be aware of another danger, the pitfall of color, the merely picturesque, color without content. Indeed, I'd begun this project like all my preceding ones, in black and white. On my first trip with Aryeh Shimron, I brought both black and white and color materials. I processed only a few of the black and white images and threw the rest away without developing them. The reason was simple: the desert consists largely of monochromatic earth colors. These colors are subtle and beautiful, but they translate into black and white as various shades of middle gray. Filters and development controls would have helped create some contrast and interest, but these wouldn't have proved sufficient. I learned such techniques from the master, Ansel Adams, but I also learned from Ansel what it means to "pre-visualize," to decide in advance what statement you're making, how to see the subject, and how to create the final print in accordance with your vision. I didn't want shades of gray, middle or otherwise; I wanted color. I wanted everyone to see the loveliness of the delicate coloration and the way it changed so dramatically according to the season and the hour of the day.\ The same map will lead different people to different places. Odd that some find this fact so hard to accept. I am told that a museum curator visited an exhibition of mine and said, "If Francis Frith photographed that area in black and white, why does Neil Folberg need color?" One of the main reasons Frith photographed in black and white was that color photography had yet to be invented. In quest for more "scientific" accuracy Frith and many others of his period would almost surely have used and loved color.\ Many of us recall the days when "art films" were made exclusively in black and white, and only the slick commercial films in color. In the art world there is a certain snobbishness about black and white. This doesn't concern me; each medium has its uses. Nevertheless, there is a danger of mistaking color for content. It is an error I've certainly tried to avoid.\ There are those who say that the viewpoint of my photographs is distant. Quite right; but I hope it never seems detached, for my involvement with the subject is intimate. My viewpoint enables you to wander through the photograph as I have wandered through the landscape. You must be given the opportunity to choose your path as I have chosen mine. While walking through the desert, one thinks of many things. I present a setting and a mood (this generally having been determined by my mood when the photograph was made). I want you to use your imagination, to think your thoughts—in short, to wander and wonder. I don't care to confine you by imposing my convictions on you. Derive pleasure from being with me in the places I have been. As John Fowles wrote, "We...know that a genuinely created world must be independent of its creator; a planned world (a world that fully reveals its planning) is a dead world."

Note to the Second Edition Introduction Egypt Sinai Jordan Israel Neil Folberg in a Desert Land by Nitza Rosovsky Acknowledgments Index

\ Library JournalIn this large, heavy, and luxurious book of color photographs of the Near East, Folberg's focus is the natural beauty of the rugged landscape rather than political turmoil. The images, splendidly seen and reproduced, are grouped by regionEgypt, Sinai, Jordan, and Israelwith each group accompanied by an interesting narrative by the photographer. Annotations for the photographs, together with small black-and-white reproductions, occupy a 30-page addendum. Nitza Rosovsky, Harvard Semitic Museum curator, provides an illustrated essay on the history of photography of the area. A beautiful book worth having. Frank Davidoff, formerly Consultant, CBS Broadcast Group, New York\ \