In My Brother's Image: Twin Brothers Separated by Faith after the Holocaust

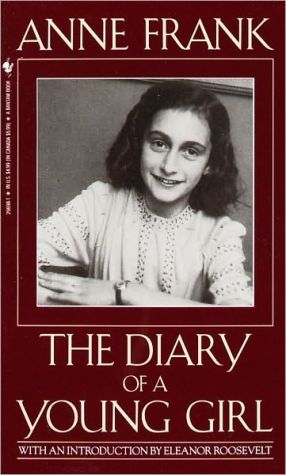

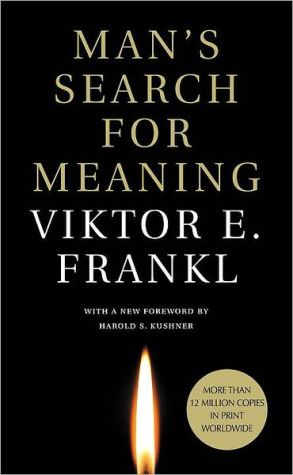

In My Brother's Image is the extraordinary story of Eugene Pogany's father and uncle-identical twin brothers born in Hungary of Jewish parents but raised as devout Catholic converts until the Second World War unraveled their family. In eloquent prose, Pogany portrays how the Holocaust destroyed the brothers' close childhood bond: his father, a survivor of a Nazi internment camp, denounced Christianity and returned to the Judaism of his birth, while his uncle, who found shelter in an Italian...

Search in google:

"Highly readable and deeply inspiring. . . . I recommend it to all readers who wish to know more about what happened to European Jewry during the Holocaust." (Elie Wiesel) In My Brother's Image is the extraordinary story of Eugene Pogany's father and uncle-identical twin brothers born in Hungary of Jewish parents but raised as devout Catholic converts until the Second World War unraveled their family. In eloquent prose, Pogany portrays how the Holocaust destroyed the brothers' close childhood bond: his father, a survivor of a Nazi internment camp, denounced Christianity and returned to the Judaism of his birth, while his uncle, who found shelter in an Italian monastic community during the war, became a Catholic priest. Even after emigrating to America the brothers remained estranged, each believing the other a traitor to their family's faith. This tragic memoir is a rich, moving family portrait as well as an objective historical account of the rupture between Jews and Catholics. Author Biography: Eugene L. Pogany is a practicing psychologist in Boston. A frequent speaker on anti-Semitism and Jewish-Catholic relations, he has written for Cross Currents, Sh'ma, Jewishfamily.com, and the Jewish Advocate. Publishers Weekly Here is an eloquent memoir of a family ripped apart by the Holocaust. Born into a Jewish family, Pog ny's grandfather, B la, converted to Roman Catholicism before WWI so he could work in the Hungarian civil service. A few years later, his wife, Gabriella, and their six-year-old twin sons, Mikl s (the author's father) and Gyuri, were also baptized as Catholics. Gabriella took her new religion more seriously than her husband and was delighted when Gyuri became a priest. At the outbreak of WWII, he was in Italy living with Padre Poi, a noted Catholic mystic, and he remained there for the duration of the war. Initially, their status as converts protected Gabriella and Mikl s (B la died in 1943) from the Nazis, but not for long--Mikl s was interned in Bergen-Belsen and Gabriella died at Auschwitz. After the war, Mikl s settled with his wife in the U.S., where, revolted by the passivity of Christians during the Holocaust, he returned to Judaism. A few years later, his brother also arrived in the U.S. and became a parish priest in New Jersey. But as Pog ny, a clinical psychologist, movingly explains, the war created an unbridgeable emotional gulf between the brothers: Mikl s couldn't forgive Gyuri, who could not, or would not, acknowledge the savageness of the persecution of the Jews, not only by the Nazis, but by Hungarian Christians as well. Gyuri, in turn, considered Mikl s's return to Judaism to be a betrayal. Pog ny deftly conveys the power of the brothers' feelings as he relates this tragic story. Author tour. (Oct.) Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\|

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ Departing\ \ \ Salus extra ecclesiam non est.\ (Outside the Church there is no salvation.)\ St. Cyprian\ \ \ \ On a fine spring day in Budapest, in 1914, Béla Pogány (né Popper), a recently trained veterinarian, knelt before a Roman Catholic priest at the Regnum Marianum Church to receive entry into the Catholic faith through the rite of baptism. The priest drew water from the baptismal font and poured it freely over the forehead of this short, stout man with brown, careworn Jewish eyes and high cheekbones like a Magyar's.\ As the celebrant chanted, "In nomine Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti," Béla's thoughts wandered from the Lord he was about to accept into his heart to his beloved wife, Gabriella, and their two-year-old twin boys. Béla was a practical man not given to religious reverie or philosophical reflection. But I am willing to imagine that by the power of this solemn and mysterious ceremony, his life passed before his eyes as if he were about to die, as he presumably was—from the life of the body—to be born again to the life of the spirit in his new Lord.\ Béla's background provides only an incomplete picture of how he had come to such a pivotal juncture in his life. He had been brought up by professed but less-than-perfunctory Jewish parents in Galgocz, a small town in the northwestern, Slovakian region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His birth was recognized by the Jewish community, his birth certificate signed by the rabbi of thetown. On the document, biblical names of his family members, such as David and Isak, appeared alongside appropriated German ones, like his grandfather's, Adolf. Slovak and German were spoken at home even more freely and fluently than Hungarian. The family knew only fragments of Yiddish and even less Hebrew. But for those few socially obligatory occasions when they might have attended synagogue services or spent holiday evenings at friends or neighbors, they were not at all religious. As a family, they observed none of the Jewish holidays or ritual practices. Béla's father had no interest in religion. His mother, Regina, was independent, intelligent, and completely secularized. She would have stayed working at her sewing machine on Yom Kippur had her family members not restrained her.\ Jewishness for my grandfather's family was a fact of social life, not of religious identity or practice. The family's four children received no religious education—no bar mitzvahs for the sons or training for the daughter in setting a Sabbath table or keeping a Jewish home. The boys, however, were circumcised. For Jews of any inclination in Hungary at the time, it was a foregone conclusion that their male children would receive the B'rit Milah of circumcision, thereby bringing them into the Hebrew covenant. To do otherwise would have surely antagonized the small, closely knit, even if not uniformly religious Jewish community of the town in which they lived and did business. For practical reasons, they could not afford to perturb that community because the success of the family's brewery was as dependent on the area's Jews as it was on non-Jews, despite the reputation of the former as nondrinkers.\ Béla's motivation to become a Christian probably stemmed from his years in Budapest, where he had arrived in the autumn of 1901 at the age of eighteen. He entered a five-year course of training at the Veterinary University, which would enable him to attain his supposedly lifelong ambition of being an animal doctor. The uninspired manner with which he pursued those studies over more than a decade would suggest that his ambition was less than fierce. The coffeehouses that lined the inner city of Pest had a much more magnetic allure to such occasional students than the lecture halls and laboratories of the university. And Béla's family didn't seem to mind indulging his protracted student life.\ In Budapest, Béla circulated in a predominantly Jewish, bourgeois culture. Yet he was at best only ambivalently tied to that culture and almost completely disconnected from its religion and tradition. He never fully recognized the matter-of-fact sustenance he received from the familiarity of his Jewish brethren, much as a fish never recognizes the water in which it swims. Instead, like the other Jews with whom he associated, he acted as if Jewishness and Judaism were merely a part of his ancestral identity that only minimally figured into who he was and how he saw himself. As a result, he lived along the surface of that culture, never exploring its depths and never taking into account the buoyancy he gained from living in what was certainly a prosperous and creative era for Jews in Hungary.\ At some point, however, the realization of his Jewishness did break into Béla's awareness, with an event that became part of family lore. It supposedly took place on a blustery winter afternoon as he sat with some friends huddled over steaming coffee at a favorite café near the university. In the midst of this subdued atmosphere, a disheveled and wild-looking patron, who had earlier been sitting glumly in a corner averting anyone's gaze, suddenly shot to his feet and accused the café owner of cheating him on his change and pandering to the Jews. Reaching across the counter and grabbing the terrified proprietor by his shirt, the enraged customer howled, "What kind of Jew nest is this? You rob me and treat me like I'm inferior to these swine." Slamming the owner against the rear wall and knocking him senseless, he glared at Béla and his friends, screaming, "You dirty Jews. You think you own this city. You drink our blood and act like innocent lambs. We'll have our revenge some day. Our Lord's blood be upon you and upon your children." Then he stormed out, leaving the other patrons to stare after him in shock and disbelief.\ Until then, Béla had not been keenly aware of the ages of discord between Christians and Jews in his native Hungary. In his own personal experience, he had known only indirectly of anti-Jewish sentiment and agitation. A year before his birth, there had been a notorious case that revived the age-old "blood libel" against the Jews that had stained the European landscape since the Middle Ages. A Jewish man, a ritual slaughterer in the distant town of Tisza-Eszlár, had been accused of killing a Christian girl and using her blood to make matzahs for Passover. The Jew had eventually been acquitted after a highly publicized and lengthy trial, but Béla always remembered how his family talked for years about the rioting that had taken place in the wake of the verdict, as close by as the city of Pozsony, only thirty miles from his family's home. The story had planted a small but enduring seed of fear in his own heart and the hearts of many Jews who otherwise enjoyed a privileged and protected life in the Hungarian kingdom.\ After the enraged patron exited the café, Béla turned to his friends, and, with a mixture of naiveté and denial, asked, "Whose blood be upon whom? What's this crazy man saying?" But even as he spoke those words, he felt the stirring in his gut of a mysterious and ancient terror that awakened memories, not in his mind but in his bones—memories of being hated and hurt. Béla wondered if these were real memories from his childhood or residual fantasies of what it meant to be a Jew. And were they his alone or were they shared by all Jews? He wanted to forget the whole incident, but he couldn't. Where had this poisonous hatred come from and where would it end?\ \ \ In truth, even after that day, Béla was still far from the baptismal font. He did not care enough about Judaism to embrace it, but neither did any other religion interest him. And he didn't feel sufficiently threatened by these occasional moments of fear to want to run away from his Jewish identity. He was content enough to live as a nominal Jew in a culture and a nation that had been, for the most part, immensely hospitable to Jews.\ This would change after Béla met his future wife, Gabriella Groszman. On a late spring day in 1907, he stopped into the B. Fehér tailoring house, an elegant shop in the fashionable inner city of Pest, to purchase a suit of clothes. By chance, Béla happened upon a young woman who worked there as a bookkeeper and office manager. He was immediately drawn to her beauty and vibrancy. Perhaps it was an attraction of opposites, for her focused energy was in sharp contrast to his casual manner. Yet her vitality seemed balanced by a subtle reserve. Her smile was warm but reluctant. It needed gentle and whimsical coaxing. And beneath the sparkle in her eyes he sensed a hint of deeper sadness and remoteness—not aloofness, but rather fragility and vulnerability—which made Béla feel safe.\ Acting on the impulse of the moment, he invited Gabriella for coffee when she was free. They met at an outdoor café one warm spring afternoon. Custom demanded that they be accompanied by a chaperone, so Mrs. Ledényi, an older woman with whom Gabriella worked, went along with her. As soon as the couple, undeterred by their lack of privacy, began to share bits and pieces about themselves, they immediately if tacitly recognized the differences in their respective stations in life. His family was well-to-do, hers was poor. But there was an instant rapport between them. He was thrilled by her intelligence, by her eloquence in Hungarian and fluency in German, which she had, like most Hungarian Jews, learned at home (in her case, aided by her father's long stint in the emperor's army). She had read novelists and poets in both languages, writers with whom Béla himself had only passing familiarity. For her part, Gabriella was amused to find that such a bright, well-bred, and seemingly ambitious man knew more about the interior of various coffeehouses in Pest than about the anatomies or breeding practices of the animals he was supposedly studying and about which he could speak so glibly. He was drawn by her intensity; she was taken by his affability, by his gentle, ingenuous manner. He was easy to like.\ They saw each other again, at first, not too frequently. As months passed, they began a more serious courtship, as much as Béla was capable of anything serious or sustained. His comfort in her presence never vanished, and he became assured, as she did, of the growing inevitability of their union. But that union was not a foregone conclusion. Béla's family opposed it from the start.\ \ \ * * *\ \ \ The need and the occasion for converting to Catholicism would not come until later. But a fatefully overheard comment and a clash of sensibilities added to its eventual desirability. It may have crystallized in one day, at a family Passover seder in 1911, four years after my grandparents met and three years before my grandfather actually converted. The seder, if it could be called that, might just as well have been an Easter celebration, for there was no ritual observance of the Jewish holiday. As far as Béla was concerned, the overriding purpose for the occasion was to allow his stuffy relatives to meet and evaluate Gabriella. Some of them had already met her, but so far the response was not encouraging: they simply didn't think she was good enough to marry into their family. So when Béla received the invitation from his sister, Laura, he considered the option of declining it. He didn't realistically believe that his convention-bound family members would warm up to Gabriella, but since he foresaw no particular danger, he couldn't very well refuse the invitation. He accepted.\ As Béla and Gabriella got off at the tram stop and walked down Damjanich Street toward his sister's well-appointed, sumptuous flat in the predominantly Jewish area of Pest, they were a modest-looking couple. Their plain attire contrasted with that of many of the other more fashionable passersby, as well as with the atmosphere set by the ornate marble facades and elaborately carved friezes of the buildings lining this street in the Seventh, or Elizabeth District of Pest. Gabriella's cloth coat was handsome but unpretentious. Béla, who could easily afford to dress more lavishly, wore one of his two dark woolen suits with a brown tie. But his mind was not on clothing fashions or architecture. All he could think of was his family. He was already imagining the persistent rumblings going on inside his sister's apartment about the couple who were supposed to be the guests of honor.\ Béla had visited his sister and her family many times and thought he knew precisely what he was walking into. In his mind's eye, he saw the spacious apartment with its high-bourgeois decoration—the Austrian crystal chandelier over the massive, distinctively Hungarian mahogany dinner table, the heavy plush drapes over the windows, the rich Persian rugs on the floors, the lavish French tapestry on the wall. He had little use for this ostentatious display of wealth. His own tastes were simpler, and he usually found his sister's apartment stuffy and oppressive.\ He squeezed Gabriella's hand as he thought of their host, his brother-in-law Károly (Karl) Schneider, the unquestioned patriarch of the family. Karl's marriage to Laura seemed an unlikely coupling, as it had little to do with love; she had been a stunning young beauty and he was twenty-five years her senior. But Karl was such a wealthy and successful man that Laura's parents couldn't imagine refusing when he asked for her hand in marriage. Now he was a heavyset, overbearing man in his sixties, smug, self-satisfied, and always convinced that he knew best.\ Béla imagined Karl impeccably dressed in his customary formal black suit, high-collared white shirt, and crimson silk tie. He envisioned him in his drawing room, sitting in a Queen Anne armchair upholstered in green and gold brocade, holding forth for his guests, passing judgment. One hand would be raised to underline a point, the other holding a cordial glass of Tokay from his vineyard in Mád, wine that he had presented at the courts of the emperor and czar. "But she's just an office girl," Karl would proclaim in his commanding bass voice. "How could a young man with such a promising future and a family of such means marry an office girl?"\ One entire wall of the drawing room was covered, from floor to ceiling, with a pastoral landscape. It had been painted by a local artist of growing renown and Karl took great pride in it. Béla could readily envision his brother-in-law rising from his chair to pose in front of the prized canvas, the very image of a wealthy, strutting Budapesti Jew, as if Karl were patronizing the humble peasants in the painting. Karl would shake his head with mock pity and say, "Yes, just a poor Jewish girl ..."\ Béla had heard this refrain before, but as it played in his mind he could feel the muscles of his stomach tighten. He longed for an ally in the group, someone in the family who would take his side. Perhaps it would be his recently widowed mother, Regina, who had come from their village of Galgocz to live with Karl and Laura after Béla's father died. He had reason to hope. During a number of family discussions about Gabriella, Regina had said, "So she's poor and doesn't have a dowry. So what?" Regina herself had become a prosperous woman who knew all too well the importance of wealth and social standing for her children's well-being. But neither had she, Béla realized, forgotten her own humble origins. Béla had heard her say many times, "We didn't exactly come here from the court of Maria Theresa."\ In his need to find comfort, and to ease his growing sense of dread, Béla imagined his mother defending Gabriella. Karl needed to be deflated, and perhaps only Regina had the sass to do it—if not in reality, then at least in Béla's wistful reverie. "It's not as if she's some Hasidic girl," Béla imagined his mother saying, "who just got off the train from Galicia and had to have her marriage arranged by her family." The subtle dig at Karl would, of course, be inadvertent. "She has only a stepmother who is gracious and proper and not in the least anxious about marrying her off." What relish Béla took in these private mental conversations. "Let her be," Béla longingly fantasized his loving mother saying. "She may seem unapproachable, but she's quiet and reserved, very modern, and better read than you or I. She's simply more nervous and frightened of all of you than unfriendly. And Béla adores her. Don't dare hurt their feelings."\ Although he'd fantasized them out of whole cloth, his mother's imaginary words offered Béla some comfort as he and Gabriella, still holding hands, walked up the two flights of stairs to Laura and Karl's apartment. They paused on the landing. Béla gazed at Gabriella. He loved the way she looked—her sculptured face, her sad eyes, her modest, unpretentious appearance. He squeezed her hand again and said softly, "Remember what I told you about my family, especially Karl. He doesn't have much good to say of anyone." She nodded and returned a faint smile, as if everything was all right. But her hand was cold and he saw apprehension in her eyes. He swallowed hard, wiped his sweaty palms against his trousers, and pulled the bell cord.\ The chatter in Karl's drawing room muffled the sound of the bell. Laura had been in the kitchen and, not listening to the shrill commotion, opened the door herself and welcomed the couple. As she waved Béla and Gabriella over the threshold and into the foyer, Karl was obliviously disparaging Gabriella with precisely the same tone that Béla had imagined: "But we all know what secretaries and office girls are really hired for."\ Béla was stunned. The words struck him like a slap across the face. Then he heard Gabriella's audible gasp and saw the fleeting look of pain in her eyes. He saw her try to regain her composure as he himself tried to will away the blood that quickly rose to his flushed cheeks. He leaned closer to her and promptly whispered, "Remember what I said about Karl. He envies our happiness and makes a fool of himself."\ Karl's words still hung in the air as the couple entered the drawing room. At the sight of them, a mortified silence fell upon the scene, for the others were certain that the newly arrived guests of honor had overheard Karl's remark. They were also certain that the two had understood its meaning and intent.\ Béla would not look at Karl. He coughed to clear his throat, as if to signal his defiance of the atmosphere in the room and his disdain for the words that had caused it. But the insult had struck home. Gabriella had succeeded in masking her humiliation, and Béla was more or less able to conceal his shame and outrage. The moment would pass quickly. But neither of them would ever forget it.\ Béla resolutely introduced his fiancée to the others. They had little to say in their embarrassment and humiliation, but they awkwardly tried to be gracious. Then it was time to gather around the dinner table.\ The impromptu and now subdued festival meal went ahead without further incident. Fine domestic wine from Karl's vineyard had been readied for the occasion. No one cared that it was hardly appropriate for ritual purposes. Nor was there a proper seder plate on the table; separate dishes of parsley and minced apples and walnuts, sitting in isolation, were all anyone could remember of the symbolic Passover foods. Someone had brought matzah, almost for novelty's sake and because it was so readily available among the city's large Jewish population. These few vestiges of Jewish tradition, however, did not prevent Laura from baking the breads—forbidden on Passover—and cooking the nonkosher Hungarian creamed meat dishes that were the family favorites. Despite some brief and satirical commentary on the liberation of the ancient Hebrews from enslavement in Egypt, there was an undercurrent of collective embarrassment and unease among the Schneiders and Poppers, these modern, middle-class, and affluent Budapestis who somehow still referred to themselves as Jews. Feeling set apart from the others by the incident, Béla more than anyone noticed the farcical quality of the ceremony.\ Now Karl spoke up for the first time since his hateful insult. "Isn't it curious how we still call ourselves Jews when all this means so little to us?" Nobody answered, but Karl's question was merely rhetorical and he was prepared with an answer. "But there's more to being Jewish than these ridiculous rituals," he said, his tone growing more self-assertive as he spoke. "We live in the Golden Age of Hungarian Jewry, but I assure you it's not because we are such a religious people."\ "Why then?" one of the wives asked.\ Karl cleared his throat and answered. As he began, his voice was uncharacteristically subdued. "Because we are brilliant and talented and have become gloriously prosperous in this wonderfully hospitable country of ours, and all within the past fifty years. This city has been built with Jewish genius." With each word, Karl was regaining his earlier self-inflation.\ Gabriella, who had been silent and remote, raised her eyes to meet Karl's. At the same time, she raised one of her hands from her lap and placed it, with symbolic defiance, onto the table next to her plate. Her voice was steady and calm. "But in the meantime," she asked, "what has become of the soul of this city?"\ "My dear Gabriella," Karl said, as deferentially as he could muster, "Budapest gets its soul from the Christians. There are enough priests and churches to save the city for another thousand years. We have inspired its mind and heart. We have enriched this city and made it a jewel in Europe." He emphasized his words with a wave of the piece of matzah he held in his hand. "Look at the banks, the universities and professions, and the artists and writers. You're no doubt well acquainted with them. And Jewish journalists love and defend this country more than the Hungarians do."\ Karl was irrepressible, Béla thought, and on this subject he seemed especially impossible to argue with, as much as several among them would have liked to. For his imperious tone, Karl drew silent scorn, but his words were weighty. Gabriella bravely pressed on. "Why do you so willingly leave the domain of soul and spirit to the monopoly of Christians?" she asked.\ "Because they need it more than we do. The Christian spirit has always been the thread binding the Magyar masses to civilization. There are fewer of us, so in their enlightened state, they have emancipated us, so to speak, and have even made our religion virtually equal to theirs. We are as Hungarian as they are. We've shared the same history and have been here since the beginning. It's a beautiful partnership. I'm not terribly interested in their religion and they don't seem particularly worried about ours. What's more, I don't need to be involved in the Jewish religion in order to be quite content with being a Jew in this most extraordinary city and country."\ "But you must admit," said Béla, "they've also used that Christian spirit to keep us at arm's length. We don't accept their savior, and we've paid for that throughout what you call our beautiful thousand-year partnership. For all we've done for this country, we're still seen as a self-interested foreign element that panders to the aristocracy. We're as liberal and patriotic as it suits our need to get ahead. We're resented for it and we've periodically paid for it. I'm not so sure we have seen the end of it."\ There was some truth in what Béla was saying, but he had never until that moment acknowledged such acute awareness as to the status and fate of the Jews. He was drawing on his own admittedly thin personal experience with anti-Semitism and his even more flimsy political understanding. In truth, he was simply taking a swipe at Karl, at this stereotypical bourgeois Jewish admirer of the ruling Hungarian aristocracy.\ "You know, Béla, in all the time I spent in America," said his brother, Louie, reclining in his chair and twirling his wineglass between his thumb and forefinger, "I never thought you'd become such a keen observer of our Jewish culture." Louie had spent fifteen years in America, where he became a bookbinder, and had returned to Budapest following his father's death. "And this from my little brother who was always more content to be playing with animals than becoming politically educated."\ "I don't have to be such a keen observer to see the obvious. Look at how people feel about Jews in spite of how we've helped build this country. You watch: as the emperor and empire grow old, we haven't seen the end of Christian hatred of Jews." Béla himself was startled by the raw feelings that were welling up in him.\ "What are you so afraid of?" asked Karl, with a subtly dismissive wave of his hand. "You've never suffered as a Jew. And you'll probably do just fine in life with such a generous family, a good profession, and of course your lovely and devoted wife-to-be." At that, Gabriella reached her hand over to Béla's lap and clutched his wrist as if to beg him not to respond to Karl's sarcasm.\ Karl's insinuations were once again offensive, but Béla was still preoccupied with his own thoughts. And his eyes were opening. No, he wasn't terribly afraid of suffering as a Jew. But he was terrified at the prospect of having to try to make a life for himself and Gabriella in the midst of the kind of culture that Karl represented. Béla deferred to Gabriella; he did not respond. Karl had succeeded in effectively silencing both of them.\ Béla looked around the table. He glanced at his poor sister, who had done so well by wedding this pompous ass. She looked beaten down and servile. She had lost some of her former beauty, but she would be well taken care of materially for her dutiful solicitude. Béla then looked at his mother, sitting next to Laura. She was always a loving and devoted matriarch. He admired and appreciated her. He could not have survived all those years as a university student without her generosity. But this was also the same mother who, terrified for her children's welfare, had forced her daughter back into her unhappy marriage with Karl when she wanted to leave him. What made it worse, Béla knew, was that his mother privately detested Karl even while she kowtowed to his wealth and position. Béla felt blessed to have found someone in life whom he loved and who loved him in return.\ As the dinner proceeded, these frontal assaults and subtler attacks at the flanks were suspended. But, to add to their earlier wounds, the couple increasingly felt quietly but painfully excluded. Karl's bombast eventually died down, partly because of the watchful eyes of his otherwise submissive relatives. Béla sensed the tacit scorn in their pursed lips and slightly raised brows, in the hesitant, guarded questions directed at Gabriella. Somehow, she represented happiness, a rarer, unarranged, and more fateful happiness than these striving, insecure relatives were used to.\ Béla turned to Gabriella and saw her looking defeated and unable to resume eye contact with anyone at the table. With her downcast eyes, she seemed disappointed and empty. There was always so much he could tell from her eyes. He wasn't certain if she still suffered from the earlier humiliation or from the discomforting conversation at the table. But he also wondered if these religious occasions evoked a deeper and more elusive longing in her. He had noticed it before, but it had barely been talked about. He never knew what to say or think about it.\ By all outward appearances, Béla and Gabriella had survived the evening. But they were permanently wounded. On leaving Karl and Laura's home, they glanced over at each other with a combined look of relief and exasperation, as if they had been forced to hold their breath for three painfully long hours and could now once again freely draw air. They stood silent for a moment in the soft glow of the gaslight street lamp in front of the apartment. Béla spoke first. `"You know we can't go on living among them."\ "I know," Gabriella said, as the pent-up tears streamed down her face. "They expect too much of me, and their disappointment is painfully obvious. They treat me like I'm a gold digger. I don't think they ever really wanted us together."\ As Gabriella spoke, Béla sighed and sputtered with indignation, "They're jealous, especially Karl, that our marriage will not be engineered by our families. My poor sister has suffered all these years from her supposedly successful marriage. She's never found happiness, but even she is infected by the scorn."\ They walked down the street arm in arm. The district was alive on this cool spring night with the murmurs of Jewish families conducting seders in their homes. From the open windows of the more religious Jews they heard Hebrew songs and blessings drift out on the night air.\ "You're hurt over the seder?" asked Gabriella.\ "No, I only wish I were more so. It means less to me than I want to believe." Béla had never truly found any sustaining warmth or light in his religious tradition. For that matter, he had never sought any protection from the cold or dark, neither of which he particularly feared. The cold was as familiar as the chill in the spring air. And the dark was tolerable, for he was a practical man not given to much soul-searching. As for the darkness inside others, it had only touched his life on rare occasions and not inspired any need to hide or flee. "What bothers me intolerably," Béla continued, looking straight ahead, feeling too embarrassed to look at Gabriella, "is the haughtiness and divisiveness of my Jewish family. I need to get away from them. I think we both do if we are ever going to survive."\ "It bothers me as well," said Gabriella, "terribly, especially the emptiness that you mentioned at religious occasions like this. I know God speaks to us through the stories of his chosen people. But people don't see it." Béla was coming to understand that Gabriella feared the emptiness, the hollowness of a life that didn't speak to her soul. Unlike himself, she needed warmth and light, and was disheartened not to find it in Béla's family's Passover celebration that night, nor in their common religious tradition or culture. Béla needed to depart, Gabriella to arrive. But they hadn't yet found a common path, nor was the time ripe.\ \ \ * * *\ \ \ On a cold January day, soon after the New Year of 1912, Béla and Gabriella were huddled next to each other on a wooden bench in the hallway of a drab Budapest courthouse. They were waiting outside the chamber of a justice of the peace who would marry them. Four or five offices with wooden doors and opaque glass windows bearing the names and titles of their occupants lined the narrow corridor. The air was stale from the tobacco smoke that wafted endlessly through the stark public hallway.\ "I'm so relieved we can do this in a civil ceremony," said Béla, "rather than go through the ordeal of a religious one with our families involved."\ "Yes, I suppose we're reaping the benefit of the enlightened ruler of this holy empire," said Gabriella, exaggeratedly inhaling the musty air as she began to be warmed by the heat of the building's clanking radiators. "He's even provided a hearth and sweet incense to adorn our ceremony. May God bless him." Not many years before, Emperor Franz Josef had invoked the institution of civil marriage. Hundreds, even thousands of Hungarian couples had since exercised the option, much to the chagrin of the various Christian churches as well as the rabbinic leaders of the country.\ Béla quickly felt Gabriella's sarcasm and consternation. "You obviously are not very happy with this."\ "I'm sorry. I don't mean to be so harsh." Gabriella's tone softened and she reached for and tenderly held Béla's hand. "You know that I am very happy. I have always loved you and I'm certain that you love me." After a pause, she continued, "But I wanted to be married in the presence of God, not just in the presence of official witnesses in a court of law, in the dead of winter. And I wanted to do it with our families' blessing, without feeling that we were going behind their backs." She was still shivering slightly from the cold outside, her teeth clenched together so that they wouldn't chatter. But there was a sweetness to her voice.\ "Of course, my dear one, I love you, and I would like the same thing." He hesitated, then continued, "But that's not reality." His smile stiffened. "My family would have come, begrudgingly, but we would have felt their disdain. Look, I've made my choices. We're not going to live the way they do. And," he added as an afterthought, "I can't imagine you'd want to have your stepmother present."\ "I know, we've been through this already. But she's happy for me, and don't forget she likes you very much—not because of the life you can provide me, but for who you are. I felt bad that I couldn't invite her, or even my aunt Bertha and cousin Elza. Having Bertha here would have been as close as I could come to my dear mother being present. And Elza's my best friend. But I accept that we couldn't have family here—not yours, not mine." Gabriella's words trailed off on a note of resignation.\ Béla went on disjointedly, without fully acknowledging Gabriella's feelings. "And what kind of religious ceremony would have been more meaningful than the uninspiring Jewish ones to which we've been such strangers?" There was a pause. Béla knew that Gabriella was not disagreeing with him. But her eyes evaded his. He knew something was missing for her and he had come to believe that, indeed, it was a spiritual and religious matter. But he still didn't know how to address it.\ Neither of them spoke for a minute. "I know we'll find our way and I'm not any less happy for this moment," Gabriella finally said, trying to reassure Béla. He didn't believe her but felt comforted nonetheless. Béla knew that Gabriella would never complain, but in the back of his mind he reminded himself that the woman who was about to become his wife was searching for something more than material sustenance and comfort, and that her life would not be complete without it. Even though their marriage would not be religiously sanctified, they both knew what a triumphant achievement it was. It was not only a public tribute to their love but also a monument to their strength and will to separate themselves from a commanding family and a binding culture. And it had taken them almost five years from the time they met to finally get to this musty, cold hallway outside the office of the justice of the peace.\ \ \ A few days after the wedding, Gabriella moved from her family's flat in Buda to Béla's apartment in Pest, near the university. By that spring, Béla was preoccupied with preparing for his final examinations and the completion of his studies, after more than ten years as a habitual student. Following his marriage, he had instantly become serious and focused about his work. His mentor at the university kept Béla on as a veterinary assistant and part-time instructor, which helped the couple make ends meet.\ Virtually within weeks, Gabriella was blessed with a pregnancy. In early autumn, she gave birth to identical twin boys, György (who would always be called Gyuri, or Georgy) and Miklós. Family lore suggests they were each born in a caul—an unbroken amniotic sack—which, according to legend, is a sign of individuals who will fulfill lives of destiny. The boys were small and dark, with the high cheekbones of their father and the large, brown, sad eyes of their mother. From the moment of their birth, it was difficult for almost anyone to tell them apart.\ Béla's family, unmindful of the aloofness he and Gabriella had put between them, descended on the couple after the children were born. Regina was thrilled that her youngest son was now the father of two boys. Laura, who had four children of her own, seemed ready to moderate the distance at which Gabriella was kept by the family, in deference to the newborn sons. The fact that the boys were, in the natural course of events, circumcised according to Jewish ritual had nothing to do with the influence of either of the couple's families, nor was it a sign of the parents' determination to perpetuate the Hebrew covenant. Just as with their father before them, it was unthinkable for these Jewish boys not to be ritually circumcised. The rabbi insisted on it and carried out the B'rit Milah with both boys at the couple's home. That Béla and Gabriella agreed to this, even without much devotion or fanfare, was, nevertheless, a significant event. Gabriella, more than Béla, was concerned with giving her children more of a religious heritage than either of their parents had received. Beyond that, she may also have overestimated the importance to Béla's family of this Jewish ceremony. Frequently solicitous of them, she was unwilling to disturb their supposed Jewish sensibilities, especially regarding as ancient a tradition as circumcision. The children's subsequent exposure to Jewish ways, however, would not exceed that which their parents had themselves experienced.\ \ \ * * *\ \ \ It was a brisk day toward the end of March in 1914. Gabriella was in the third month of her second pregnancy. Her active two-year-old boys were momentarily occupied by their step-grandmother, who was visiting and helping mind the twins, whom she adored. Béla had just finished teaching an anatomy class at the university. On his arrival home, he hurriedly coaxed Gabriella to sit down in the drawing room. He took the soft velvet armchair and she sat on the Victorian sofa to his side.\ "After class, I met with Professor Nagy and he offered to submit my name for a civil service job as the animal doctor of a small village called Báránd, not far from Debrecen and next to Püspökladány." Speaking in one breath, Béla could hardly get the last few words out.\ Gabriella could barely respond. She was as dumbstruck as he had initially been. "What?" she finally managed to utter. "That's ... marvelous!"\ "Of course, it's a big decision. Life would be harder and I'll never get wealthy as a civil servant. You know that the civil service is called the `mule's steppingstone.'"\ "Well, you're obviously no mule," Gabriella managed to inject. "At least not anymore," she said, poking fun at her husband. "But we've always lived modestly. We'd manage."\ "And I've always believed rural life would be our natural element." His hands moved to the quick tempo of his words. Barely managing to stay seated on the edge of his chair, he went on impetuously, without giving his wife another chance to respond.\ "But there is something further I have to tell you about this," he said, rising from his armchair and trying to check his excitement by clasping his flailing hands together and holding them still under his chin. "It's an important matter we'll have to give much thought to."\ "How much more important could it be than what you just told me?" Gabriella teased with a smile, raising an open hand in a gesture of playful naiveté. "So, end the suspense and tell me what it is."\ "You know Nagy wouldn't do this if he didn't like me. And you know his feelings about Jews."\ Gabriella looked puzzled. "Yes, it's always been peculiar, but it's not news. He's done well by you, and you by him. But what of it? Don't keep leading me on this way."\ "Well, he seemed to have my best interests at heart when he told me." Béla was still hedging, but then he blurted it out. "You know how difficult it is for Jews to be appointed to the civil service. Nagy suggested that we Christianize our surname and cross over to Christianity. It might be our only chance, and it would be a way of blending in with the community and not becoming too isolated in a place with only a small number of Jews living there."\ Gabriella appeared not to hear any of the words after "Christianity." She turned her head slightly away from Béla and gazed off into space, looking through things, not really at them. He recognized that she had turned inward, toward her private thoughts and feelings. "That sounds like a good idea," she said in a measured, understated way. "We'll truly be making a new home—won't we?—with a new faith and a new community." Béla thought he could detect a tone of peace and contentment that he had hardly heard before.\ He himself could not have thought of a better way to accomplish all that he wanted to in regard to his hovering and hostile family. Leaving Budapest would separate him from them and allow him to live by his and Gabriella's own standards and values, which were so different from theirs. He had never wanted to be a visible and wealthy Budapesti Jew. He just wanted a simple life as a country veterinarian. And Catholicism, what a brilliant way, he thought to himself, of loosening his emotional ties to his family and his culture. He didn't much expect Catholicism to save his soul. But maybe it would give him a livelihood and free his spirit so that he could live a life of his own choosing.\ Béla felt exhilarated. He laughed. "Then we'll go. We'll tell the children and our families, and we'll go. We'll work out the details, but for now I may have to proceed faster than you and the children need to, at least as far as our name and our professed religion." As far as Béla was concerned, the religious matter didn't really require as much thought as he had let on. And he was instantly encouraged by Gabriella's apparent euphoria. The children and their grandmother Rosa had entered the room and they shared in the excitement and anticipation.\ In subsequent days, Béla informed his family of his decision to accept the position in Báránd. They were shocked at first and became increasingly forlorn that they'd be losing contact with him and his family, especially at such a tender time in his children's lives. But they realized soon enough that Béla could not go on indefinitely working as an assistant at the university. His mother had hoped for a university appointment for him, but in two years it had not materialized. When he told them of their decision to convert to Catholicism, his family seemed indifferent in their response. Indeed, they recognized that it would be prudent for them to blend in with the local population. Appearing in their new rural home as worldly and bourgeois Jews from Budapest was simply unwise. They all seemed to accept Béla's decision matter-of-factly.\ Shortly before he was baptized, Béla decided to proceed with changing his family's name and "Hungarianizing" it. Most Jews, even religiously observant ones, had already taken on Hungarian names soon after the turn of the century. It was not in the least unusual to alter the country's "motherbook" of the names of its citizens, thereby making Jewish Hungarians indistinguishable from Christian ones. Béla chose to change his surname from Popper, a name fairly common, among Jews with German or Austrian roots, to Pogány, a Hungarian name equally unexceptional except for the fact that the word means "pagan," that is, one who is neither Jew nor Christian. By choosing it, Béla was not proclaiming himself a heathen. The name signaled that he was neither embracing Christianity nor necessarily forgetting his background as a Jew. He may have been simply indicating the utilitarian nature of his new identity.\ The couple decided that Béla would be baptized first, before Gabriella and the children, because he had to proceed quickly, and it enabled them to keep up the appearance that conversion was nothing more than a practical consideration. In a month or two, Gabriella and the boys would follow Béla into the church and then to their new village, where he was to begin working that summer.\ \ \ * * *\ \ \ By his solemn Latin incantation, the priest announced Béla's spiritual rebirth, such as it was. "God the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ has freed you from sin ... so may you live always as a member of his body, sharing everlasting life." At the very end of the ceremony, the priest placed salt on Béla's tongue, an ancient part of the baptismal rite indicating the likelihood that members of the fledgling church would be persecuted. "Everyone," says the Gospel of Mark, "shall be salted with fire." Ironically, the book of Leviticus in the Jewish Bible is the source for this institutionalized anticipation of victimization. There it is instructed that all sacrifices offered up to God are first to be salted. It is a symbol of the everlasting covenant between God and the Jewish people.\ It is difficult to imagine exactly what Béla felt about his Jewish past at this moment of conversion. Was this like the forced "convert or die" apostasy of a Marrano during the Spanish Inquisition? Was there a burning stake awaiting Jews if they felt they couldn't publicly renounce the error of their ancestors' ways? Hardly. But even Béla had an obscure sense of the scandals and threats to which Jews were continually exposed throughout his nation's history. Was he naive enough to think that he could ultimately escape the fate of Jews? Or might he have heard a small voice in the back of his mind telling him he'd never escape it, whatever that fate might turn out to be? A practical man, not given to soul-searching or philosophical contemplation, Béla's recognition of his Jewish soul would remain private, as matter-of-fact as his Christian exterior.\ At the completion of the ceremony, Béla rose to his feet, the taste of salt still on his tongue, his hands clasped prayerfully in front of his heart. He bowed respectfully to the anointing priest, then turned,and slowly walked to the front pew, where he was greeted by the neighbor who had sponsored his baptism and a few other congratulatory friends and parishioners who had accompanied him.\ Outside the church, Béla took leave of his new fellow parishioners and walked the few short blocks to his apartment alone. Gabriella was in her last months of pregnancy and had been home resting with the twins. She was on the couch when he entered. She looked up, and Béla casually but proudly announced: "I am now a Catholic." He sat on the edge of the couch, and as Gabriella embraced him she felt tears of joy fill her soul, for she herself was now a step closer to their common goal.

Acknowledgments Author's Note Prologue: Sorrow in Search of Memory Chapter 1: Departing Chapter 2: Crossing Over Chapter 3: Crucible Chapter 4: Providence Chapter 5: Harbingers Chapter 6: Exile Chapter 7: Breach Chapter 8: Flight Chapter 9: Sanctuary Chapter 10: Betrayals Chapter 11: Path of Sorrow Chapter 12: Samaritans Chapter 13: Death and Resurrection Chapter 14: Ascension Chapter 15: Reunion Chapter 16: Disarmed Chapter 17: "Jew Priest"\ Chapter 18: Revisiting Chapter 19: Memoria Passionis\ Chapter 20: Mourning Chapter 21: Remembrance\ Notes

\ Publishers Weekly - Publisher's Weekly\ Here is an eloquent memoir of a family ripped apart by the Holocaust. Born into a Jewish family, Pog ny's grandfather, B la, converted to Roman Catholicism before WWI so he could work in the Hungarian civil service. A few years later, his wife, Gabriella, and their six-year-old twin sons, Mikl s (the author's father) and Gyuri, were also baptized as Catholics. Gabriella took her new religion more seriously than her husband and was delighted when Gyuri became a priest. At the outbreak of WWII, he was in Italy living with Padre Poi, a noted Catholic mystic, and he remained there for the duration of the war. Initially, their status as converts protected Gabriella and Mikl s (B la died in 1943) from the Nazis, but not for long--Mikl s was interned in Bergen-Belsen and Gabriella died at Auschwitz. After the war, Mikl s settled with his wife in the U.S., where, revolted by the passivity of Christians during the Holocaust, he returned to Judaism. A few years later, his brother also arrived in the U.S. and became a parish priest in New Jersey. But as Pog ny, a clinical psychologist, movingly explains, the war created an unbridgeable emotional gulf between the brothers: Mikl s couldn't forgive Gyuri, who could not, or would not, acknowledge the savageness of the persecution of the Jews, not only by the Nazis, but by Hungarian Christians as well. Gyuri, in turn, considered Mikl s's return to Judaism to be a betrayal. Pog ny deftly conveys the power of the brothers' feelings as he relates this tragic story. Author tour. (Oct.) Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\|\ \ \ \ \ KLIATTWe continue to collect individual portraits of those affected by WW II and the Holocaust, and find astounding journeys that raise unique moral and historical questions for the reader. Dr. Eugene Pogany's memoir about his Hungarian family roots delves into the differences between Catholicism and Judaism, the tragic atrocities of the war, and candid reflections about the faith of identical twin brothers. Trained in psychology and psychotherapy, Pogany returned to Hungary and Italy to research, repeatedly questioned his aging parents about significant memories, and finally pieced together the intimate stories that make up the fabric of his family. This is not an easy middle school read; rather, it is a complex collection of vibrant snapshots that begin in 1918 and do not end until Pogany's Uncle Gyuri, the Jewish priest, dies in 1993. The Nazi definition of a Jew, the conflict of "baptized Jews," and the interwoven political and religious tensions concerning the legitimacy of conversion are expertly defined. The Catholic Church figures into this memoir, yet it is not written as an indictment of the Vatican or the Church's indifference to the Holocaust. Vivid individual portraits include a seder in Bergen-Belsen, reciting kaddish for Grandmother Gabriella who perished as a Christian martyr, and returning to Hungary with his 84-year-old father to view his parents' graves. Through convincing dialogues and historical narration of the events of the day, this excellent memoir raises a multitude of questions about devotion and allegiance that would satisfy high school-level research. Highly recommended. Category: Biography & Personal Narrative. KLIATT Codes: SA—Recommended for seniorhigh school students, advanced students, and adults. 2000, Penguin, 327p. illus., $14.00. Ages 16 to adult. Reviewer: Nancy Zachary; YA Libn., Scarsdale P.L., Scarsdale, NY SOURCE: KLIATT, March 2002 (Vol. 36, No. 2)\ \ \ Library JournalPrimarily an account of the author's Hungarian grandparents between 1910 and 1945, this Holocaust survivors' story brings the profound emotional effects of the trauma to life. Although from secular Jewish families, they converted to Roman Catholicism and raised their three children in that faith. Nevertheless, they were all regarded by their neighbors as Jews during the 1930s and 1940s and were treated accordingly. The couple's twin sons had very different experiences of the Holocaust. One, who had been ordained a priest, was sheltered in a southern Italian friary during the war and always refused to believe that the leaders of his Church could have failed to combat the horror. The other (the author's father) had remained in Hungary and saw most of his family transported to concentration camps; he later turned to secular Judaism. Both brothers immigrated to America, but their different experiences of the Holocaust drove a permanent wedge between them. This is also the story of the author's attempts to learn about his family, since much was not discussed when he was a child. Based primarily on interviews and conversations, this moving tale of faith and acceptance belongs in most general collections.--Marcia L. Sprules, Council on Foreign Relations Lib., New York Copyright 2000 Cahners Business Information.\\\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsThe "religiously and historically turbulent landscape of Jews and Christians in the century of the Holocaust" is explored in this tale of twin brothers (of different faiths) living through the wartime turmoil in Hungary-as narrated by one of their sons.\ \