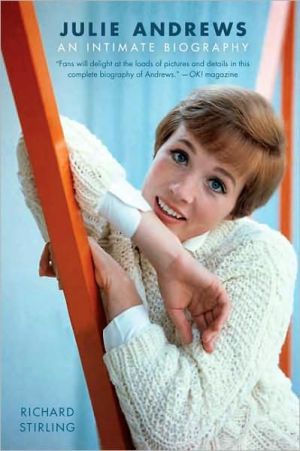

Julie Andrews: An Intimate Biography

The extraordinary career of Dame Julie Andrews spans more than forty years. Her first film, Mary Poppins, was Disney’s most successful film, and in 1965 The Sound of Music rescued Twentieth Century Fox from bankruptcy. Three years later, Star! almost put the studio back under, and the leading lady of both films fell as spectacularly as she had risen. But Julie Andrews is nothing if not a survivor; and despite many setbacks—including the tragic loss of her singing voice in 1997 after a botched...

Search in google:

Julie Andrews is the last of the great Hollywood musical stars, unequaled by any in her time.In My Fair Lady, Julie Andrews had the biggest hit on Broadway. As the title character in Mary Poppins, she won an Academy Award. And, in 1965, The Sound of Music made her the most famous woman in the world and rescued Twentieth Century Fox from bankruptcy. Three years later, the disastrous Star! almost put the studio back under, and the leading lady of both films fell as spectacularly as she had risen.Her film career seemed over.Yet Julie Andrews survived, with what Moss Hart, director of My Fair Lady, called “that terrible British strength that makes you wonder why they lost India.” Victor/Victoria, directed by her second husband, Blake Edwards, reinvented her screen image—-but its stage version in 1997 led to the devastating loss of her defining talent, her singing voice.Against all odds, she has fought back again, with leading roles in The Princess Diaries and Shrek 2. The real story of bandy-legged little Julia Wells from Walton-on-Thames is even more extraordinary; fresh details of her family background have only recently come to light.This is the first completely new biography of Julie Andrews as artist, wife, and mother in over thirty-five years—-combining the author’s interviews with the star and his wide-ranging and riveting research. It is a frank but affectionate portrait of an enduring icon of stage and screen, who was made a Dame in the Millenium Honours List. Once dubbed “the last of the really great broads” by Paul Newman, she was the only actress in the 2002 BBC poll The 100 Greatest Britons. But who was Dame Julie, and who is she now?This is her story. Publishers Weekly London-based stage/TV/film actor Stirling brings up the house lights to detail the entire life of the performer he has known since 1986. Having previously written about Andrews for the Evening Standardand other publications, he highlights recollections of her associates, in addition to his extensive archival research, plowing through some six decades of reportage and interviews in magazines, newspapers and books. Stirling grabs the reader's attention on the opening pages with a description of Andrews's 1997 Mount Sinai Hospital throat surgery, a normal operation that went tragically wrong: "Her principal trademark, the voice of mountain spring purity, was gone, as astonishingly as it had first appeared." Beginning with her childhood in London during the Blitz and youthful voice lessons, Stirling traces her career from post-WWII performances on BBC Radio and the London stage to her 1954 arrival in America with The Boy Friend. After acclaim for My Fair Ladyand Camelotcame the caravan of TV and movie roles that continue until the present day with voice work in the Shrek series and last year's Enchanted. The book successfully documents and details the professional and personal peaks of her life. With Andrews's memoir, Home, to be published in April, devoted fans are sure to turn to both. 8-page b&w photo insert not seen by PW. (Apr.)Copyright 2007 Reed Business Information

Julie Andrews\ An Intimate Biography \ \ By Stirling, Richard \ St. Martin's Press\ Copyright © 2008 Stirling, Richard\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 9780312380250 \ \ \ Chapter One \ \ Weather and Tide Permitting\ Julia Elizabeth Wells entered the world at six o"clock in the morning of Tuesday 1 October 1935, at Rodney House Maternity Home, Walton-on-Thames, Surrey. The healthy eight-pound baby, named after her grandmothers Julia Morris and Elizabeth Wells, was born under the star sign of the Balancing Scales, indicating what she later defined to me as her "typically Libran" ambivalence. Other characteristics – ruthless objectivity, a horror of confrontation, maintaining a positive outlook – would not be long in developing. Given the childhood in store for her, baby Julia would need them all.\ At the height of Julie worship in the 1960s, an astrologer at the London Daily Express, given only the time and date of her birth, concluded of the mystery subject:\ This woman is a fundamentally an idealistic person, and one who has a basic compulsion for harmony. She will perpetually strive to "strike a balance" – in her activities, relationships, aspirations.\ She will have a streak of reserve, due to shyness and lack of complete self-confidence; thus, she will assume a mask of apparent self-assurance which she does not actually possess . . . The personality she reveals to the world atlarge will be charming, friendly and seemingly rather naïve, but there is a part of herself which she never reveals – not so much because of a desire to deceive others, but due to her shyness and sensitivity.\ Blake Edwards later confirmed this aspect of his wife: "She"s still finding out about herself. She"s a good lady. But she"s shy."\ In one of the most negative articles ever written about Julie, Esquire journalist Helen Lawrenson thought otherwise, defining her as having "a background not customarily compatible with reticence and timidity". But there was never anything remotely customary about Julie Andrews, in personality or circumstance. Her abilities came not from her stars, but from the widely disparate natures of her parents: practical common sense from her father, and – more than she knew – artistic brilliance through her mother"s line.\ Her father, Ted Wells, the son of a carpenter, was a handicrafts schoolteacher, a quiet romantic with a deep love of poetry and the English countryside – passions he would pass on to his daughter. Winning a scholarship to Tiffin School in Kingston-upon-Thames, Ted had gained an excellent basic education, but could ill afford further study. After six years, he took up an apprenticeship with a local construction company, specialising in the production of transformers: there, he fell in love with a vivacious redhead of seventeen named Barbara Morris.\ In complete contrast to Ted, Barbara was a larger-than-life show-business personality, helping her sister Joan run a local dance school while pursuing a career as a popular pianist. Julie was taught to sing and dance – "almost from the time I could toddle" – but Barbara would play even more of a key role in her daughter"s career after marrying her second husband, Julie"s stepfather Ted Andrews.\ This much was well-documented family history, to which Julie would always have a characteristically well-versed set of responses. Yet her lineage was more disturbing, so well hidden that she was sixty-seven before she learned the story of her maternal grandparents. Only then could she fully understand her mother"s frustration and later alcoholism – and, perhaps, know herself rather better too.\ On Saturday 3 July 1976, a letter appeared in the South Yorkshire Times. Jim MacFarlane, of the University of Sheffield, had tried to research an almost forgotten local hero, commonly known as "The Pitman"s Poet". He knew the best-known examples of the writer"s work but little else, merely that the poet had left South Yorkshire in the interwar years and that his daughter Barbara had, he said, been "a very good piano player" – just as Julie would later describe her mother as "a fine pianist".\ MacFarlane made the connection for himself. "Arthur Morris, our Celebrated Colliery "Deputy" Artiste," he wrote, "had another claim to fame – as the grandfather of Julie Andrews, actress."\ At the time nobody seemed very interested. In 1976, Julie Andrews had been absent from the big screen for six years (with the exception of a low-budget thriller made by Blake Edwards – himself at a low ebb – two years earlier). Her much-vaunted television series had been axed after only one season. Even so, there was a remarkable lack of effort to contact the coal miner"s granddaughter.\ Then, over a quarter of a century later, came sensational revelations from the research of a Yorkshire solicitor, Giles Brearley, into the history of his coal-mining community. A keen historian in his spare time, Brearley had happened upon the same pieces of Morris"s poetry. He recognised them as exceptional, capturing the desperate dignity of the coal mining towns in the early decades of the twentieth century. Brearley was determined to piece together the life of Arthur Morris. After endless hours spent trawling through archives, he succeeded, and in 2004 published his fascinating book The Pitman"s Poet.\ Morris, a gregarious fellow with a fine speaking voice, had been a popular character in the mining villages of South Yorkshire, going from door to door, enveloped in a black cloak, to recite his poems. A book of his early work – containing "The Miner"s ABC", a definition of the collier"s lot – was sent to King George V. In 1924, one of his poems, "Wembley Colliery", exposed the resentment felt by many pit families at the sanitised model colliery built for the British Empire Exhibition:\ Then hats off to our miners all and hats off to their wives,\ They never know from day to day, "ere they may lose their lives.\ And do not think our collieries are quite so danger free\ As the perfect ideal pit you"ve seen called Wembley Colliery.\ When, in 2003, Brearley wrote to Julie with the new-found information, she sent her half-brother up to Yorkshire to "make sure" of him. "You know what sisters are like," Christopher Andrews explained.\ "It was amazing that Julie knew nothing of Arthur"s achievements," Brearley told me later. "I was astounded, when Chris came to visit, that the school where his mother had had so much happiness was unknown to him. He did not even know where she was schooled."\ I asked Julie"s other half-brother Donald if the news made sense of unexplained family issues. "I can"t be specific," he replied, slowly, "but some pieces of the jigsaw would certainly fit into place."\ On a Christmas trip to London, Julie hosted a family gathering at the Dorchester Hotel. So voluble was she about the discovery that Christopher had to remind her, "Remember, Jules, he"s my grandfather too."\ Previously, all that Julie knew of her grandfather was that he had served in the army. In a magazine article of 1958, she had written of him as "a fine musician . . . a drum major in the Grenadier Guards" – but "never on the stage". But Giles Brearley"s real discovery had less to do with Morris"s work than with his life – a dramatically chequered existence, culminating in a tragic and sordid end. Barbara had died in 1984, Joan fifteen years later, keeping the full, unexpurgated story to themselves. "Obviously the trauma felt by her mother and aunt was very deep indeed," Brearley told me. "Their formative years were just blotted out from memory." Their father had been a convict and – as I confirmed for myself – both parents had died horrible deaths.\ William Arthur Morris was born in 1886, possibly illegitimate, to a working-class family in the railway town of Wolverton, Buckinghamshire. Quitting his first job as a barber, he joined the Army as a volunteer in 1909 and was posted to Caterham Barracks in Surrey, where he completed training as a guardsman. The tall, handsome young soldier became friendly with a twenty-two-year-old maid from north-west Surrey. Julia Mary Ward was the daughter of a gardener from Stratford-upon-Avon, whose family had moved shortly after her birth to Hersham (then a village, later a suburb of Walton-on-Thames) to live next door to the local laundry, at Gable Cottage in Rydens Grove.\ Julia, susceptible to Arthur"s easy way with words, soon fell pregnant. The couple were married on 28 February 1910, one month after Arthur decided to extend his military service for another seven years, and one month before he was promoted to lance corporal. On 25 July, their first daughter, Barbara, was born.\ According to Giles Brearley, five days later, Arthur Morris and his new family disappeared, absent without leave. It was over a year before the Army caught up with him. At a local Bonfire Night gathering on 5 November 1912, he was spotted and arrested. Branded a deserter, he faced a court martial, and on 18 November was thrown into the cells of Caterham Barracks, where his military career had commenced with such promise.\ After a month behind bars, he was discharged on compassionate grounds, to provide for his wife and baby. Starting anew, Arthur joined the Shakespeare Colliery near Canterbury and rose remarkably quickly to the position of pit deputy, thus being exempt from the First World War call-to-arms. A second daughter, Joan, was born in 1915 – and Arthur, clearly uncomfortable with parental responsibility, disappeared once more.\ In his book, Brearley traces Arthur"s path north, where he took up work as a pit deputy in the more profitable coal mines of South Yorkshire. His family joined him at Denaby Colliery, outside Doncaster, where they integrated well. Joan was more reserved than her vivacious elder sister Barbara, who was, by all accounts, a happy and confident child, highly proficient at the school piano.\ Arthur became a key member of the local charitable lodges. Taking part in their concerts, he performed his own poems, which he had started to compose around 1920. One of the best received of these was "A Pit Pony"s Memory of the Strike", during the industrial action of early 1921:\ At last I"m on the surface; from the cage I"m led away,\ They take the cover off my eyes; I see the light of day.\ Later on my mates come up and then it came to pass,\ They took us down into a field and turned us out to grass.\ We held a meeting in that field, "twas just beside a dyke\ And we came to the conclusion that the pit must be on strike.\ As Arthur"s reputation grew, he abandoned the secure existence at the colliery for a precarious living as a poet. Moving to the more cosmopolitan town of Swinton, he continued to sell his poems, and hosted local dances at which his elder daughter played the piano; sometimes he accompanied her on drums.\ Barbara"s reputation was threatening to outstrip that of her father: she had by now performed in many of the towns of South Yorkshire, and twice at the BBC studio in Sheffield. In January 1926, passing her London College of Music examination, she seemed set for a career as a concert pianist. And then the family broke up.\ Arthur"s success in his new occupation was in part achieved thanks to the attentions of higher-born ladies, to whose houses he was now invited – at which his wife Julia was hopelessly ill at ease. Just when he succumbed to temptation is unclear, but he almost certainly contracted syphilis before Julia decided to leave him. In February 1927, she and her daughters went back south to her family home in Hersham.\ The biggest casualty of the arrangement was Barbara, whose musical ambitions were utterly ruined. At the age of eighteen, having to support an ailing mother and thirteen-year-old sister, she found work in a Surrey factory, making transformers. It was there that she met Ted Wells, an apprentice who, eager to better himself, was attending night school after a day"s work.\ To boost her family"s meagre income and pay for Joan"s dancing lessons, Barbara taught the piano. By the turn of 1928, she had an extra burden to bear. Her wayward father, unable to look after himself any longer, turned up in Hersham. Riddled with syphilis and rendered almost insane, he brought into the house another disease to shadow his elder daughter for the latter part of her life: alcoholism.\ He found work for a while as a metal polisher, but it was a hopeless case. On 31 August 1929, Arthur Morris died at Brookwood Mental Hospital, Woking, aged forty-two. The cause of death was given as "General Paralysis of the Insane", which he had suffered for some "considerable duration". Two years later, on 22 June 1931, Julia also died, only forty-four years old. The death certificate listed the horrors her husband had inflicted upon her, including tabes dorsalis: congenital syphilis. He had destroyed her, in more ways than one – but her Christian name would live on in the next generation.\ Lack of money forced Barbara and Joan to move again and again, to ever-cheaper apartments. For each move, Ted Wells lent a helping hand, borrowing a builder"s handcart to carry their one valuable possession: a piano. At one stage, times were so hard for Barbara and her younger sister that Ted sold his motorcycle for £12 to help pay their rent. It was an enormous sacrifice: as a newly qualified handicrafts teacher, he needed to travel as much as forty miles to give lessons at schools in five different villages. He now had to cover the daily route by bicycle, his only consolation being that he rode through some of the most picturesque scenery in Surrey.\ After Ted"s first term as an itinerant teacher, he and Barbara decided to wait no longer. On Boxing Day 1932, they were married at St Peter"s Church, Hersham, witnessed by Barbara"s maternal grandfather William Ward, and Ted"s mother Elizabeth Wells. On their joint earnings, they could just manage a rental of £1 a week for a prefabricated asbestos bungalow on the outskirts of town.\ Joan"s dance training had begun to pay dividends, in the form of a small dance school in Hersham, with half-hour lessons costing only a shilling. These were held in the evening at a local preparatory school, and the enterprise was very much a team effort. Joan taught, Barbara provided piano accompaniment and Ted built the props and scenery. Often working until the early hours of the morning, he created pieces such as a twenty-four-foot model of the liner Queen Mary or an elaborate roundabout, his expertise bringing a touch of professionalism to the school shows.\ Ted and Barbara Wells had now been married for over two years of grinding poverty. By living with Joan, they could just afford to support a family, so they moved to a three-bedroom, semi-detached brick house in the more fashionable Westcar Lane, Walton-on-Thames. They named the house "Threesome".\ Then, on 1 October 1935, Threesome became Foursome. The future Julie Andrews had arrived.\ Born in a trunk Julia Elizabeth Wells may not have been – but the other hallmarks of a show-business childhood were all too apparent. A stage mother, for instance. Barbara Wells" life revolved around the Joan Morris School of Dancing, and it was only a matter of time before the shows featured the proprietor"s little niece, who made her stage debut aged two, as a tiny fairy waving a wand.\ In 1986, I met Julie Andrews for the first time at London"s National Film Theatre, where she spoke of her mother and aunt"s endeavours. "Between them, with my dad"s help, they used to put on these shows in my home town of Walton-on-Thames. One of my earliest memories is of peeing my pants on stage. I was about three."\ Her assurance, even at that age, was remarkable. At the local Walton Playhouse, performing a gavotte with another little girl, Julie took control of the dance when the top hat slipped over her partner"s eyes. The following year, wardrobe problems blighted her solo routine in the pageant Winkin", Blinkin" and Nod. Co-starring as Nod, Julie wore a white pyjama suit. At a climactic moment, the buttons burst open – exposing bright pink underpants. But, totally immersed in her song, she finished to huge applause.\ "Julie lived in a world peopled with fabulous, storybook characters," Barbara recalled. "She"d stand outside the door and cry, "Now close your eyes – I"m coming in. Guess who I am." And in would walk Queen Bess or a pixie or a tough little boy. We always kept a prop box with stage clothes and accessories. It was Julie"s paradise."\ The precocious little girl did not attend an ordinary school. The decision was only partly to do with Barbara"s stage ambitions for her daughter. Although Ted Wells was employed by traditional schools, he was progressive in his attitude to education, believing in a more individual approach. He decided to teach his daughter at home.\ It seemed to work. By the age of three, Julie could already read and write, and had started to acquire, from his reading to her each night, a love of poetry. Ted also introduced her to Père Castor"s whimsical adventure stories of animals and birds. These and The Little Grey Men, by an author known only as "BB", a simple nature story of the last four gnomes left in England, set over the four seasons of the year, became lasting favourites.\ The family belonged, nominally, to the Church of England, but was not particularly observant. In her seventieth year, Julie remembered her father as believing in nature more than anything, "that religion resides inside of you". Above all, Ted shared with her his love and knowledge of natural history, teaching her the leaves of the trees and the songs of the birds, sailing with her in a hired boat on the nearby River Thames. At that stage of their lives both she and her brother John David, two and a half years younger, enjoyed a normal English childhood. "Cosy years," is how Julie later described them, "and all my memories of them are cosy."\ There was a time and a place for everything in Walton-on-Thames. On screen at the local Capitol Cinema good triumphed over evil, couples kept one foot on the ground when embracing and everyone went happily home to supper (a particular favourite of Julie"s being boiled potato sandwiches – "all squashy and dribbling butter"). Late in life, his daughter now one of the most famous women on the planet, Ted Wells retained a plaintive story she wrote at this time, of a mother"s longing for a little girl and boy: "It was Chrisms, the night Santer Claushee came to bring the two babis." Naturally, the family lives "hapleevrovter". Reality would prove otherwise. The Wells family would soon be split in two, and the happy little girl would suffer considerable torment – to what extent, she would do her best to ignore for over two decades.\ In the long, hot summer of 1939, talk of war was everywhere. Yet, for little Julia Wells, there was no indication that the suburban security of her childhood was almost at an end. Ironically, the catalyst was a trip to the seaside. Barbara had been engaged for the season as pianist to the Dazzle Company, a music-hall variety troupe, in the south coast resort of Bognor Regis. In July, Ted joined Barbara and Joan and his children, to make it a complete family holiday. It would be their last. Precipitously, a member of the Dazzle Company was injured and had to leave the show. The replacement was a burly, ginger-haired, thirty-two- year-old tenor, styled "The Canadian Troubadour: Songs and a Guitar". His name was Ted Andrews.\ Each night, he was accompanied by attractive, flame-haired Barbara, three years his junior. But, before their professional relationship could become anything else, war with Germany was declared on Sunday 3 September, and the troupe was disbanded. The Wells family returned to Walton-on-Thames. Ted volunteered for the Royal Air Force, Barbara joined ENSA, the Entertainments National Service Association (known colloquially as "Every Night Something Awful"), and Britain faced the eerie days of the phoney war, of gas masks and panicky air-raid alerts.\ A rush to evacuate schoolchildren to the countryside convulsed the country. Ted, waiting to hear from the RAF, was delegated to transfer evacuees from Surrey. While Barbara performed her initial concerts for ENSA, Julie and John were tended by Aunt Joan. Then, along with thousands of others, they were displaced from their home, evacuated to a riding school in Kent, where Julie had what she remembered as "a glorious time".\ ENSA, meanwhile, had also recruited the Canadian Troubadour. By accident or design, Barbara found herself in the same unit as her Dazzle Company colleague. This time, the inevitable happened, and the seven-year marriage of Mr and Mrs Wells was shattered.\ As the injured party, Ted was awarded custody of both his children – but, in the most agonising decision of his life, he waived the right over Julie. One reason was his failure to be accepted for RAF aircrew. His war effort would be in running a factory at Hinchley Wood in Surrey, working for up to seventy-two hours at a stretch – on one occasion, arriving home so tired that he fell asleep with his head in a bowl of porridge. "With the war work taking up so much of my time," he later wrote, "I could not do my duty to both of them as a father."\ Ted felt that "a growing girl needed a mother"s influence", but it was a second factor that had decided him. He recognised that Julie"s talent, if not her happiness, would be served by a career in show business, for which his wife and her lover were equipped to prepare her. Many years later, though, he revealed his doubts as to whether he had made the right decision, however unselfish: "I know separation from me and her brother John caused her a lot of suffering."\ In 1944, Ted Wells would remarry. His second wife, Winifred Birkhead, a former hairdresser and the widow of an RAF bomb-disposal expert, had come to his factory as a trainee lathe operator. A year later, they would have a daughter of their own, Celia.\ Having lost two members of her family, Julia Elizabeth Wells also lost her home. The thin little five-year-old girl was now to live at 1 Mornington Crescent, in Camden Town, north London. Thirty years earlier, the brilliant artist Walter Sickert (suspected of having been Jack the Ripper) had lived at No 6. Even then, the street had been in decline.\ By the time Ted Andrews and Barbara took rooms in the corner building, backing on to the railway tracks from Euston Station, it was a grimy, unfashionable location.\ Instead of the leafy views of Surrey, Julie now looked out at a mammoth, quasi-Egyptian temple, the entrance flanked by two seven-foot bronze cats: the Carreras Factory, home of the famous Craven "A" ("for your throat"s sake") cigarettes. While her stepfather was still alive, Julie laid her ambivalence aside to recall "the bleak turn of events: I hated my new house and the man who seemed to fill it."\ Compared to the quiet, thoughtful Ted Wells, the other Ted, "with a personality as colourful and noisy as show business itself", seemed an unbearable substitute. Even his singing "made the tooth-mugs jump on the bathroom shelves". Barbara suggested that she call him "Uncle Ted", but Julie remained stubbornly determined to resist him.\ The lovers had formed a variety act, with which they would eventually tour the country from Brighton to Aberdeen. As Barbara later described it, "We were never top of the bill. After all, we were musical and not comedy, and the comedians got the best billing. But we were the second feature, a good supporting act with a drawing-room set and ballads – nice, family-type entertainment."\ For the moment, their work for ENSA was very badly paid. And there would soon be another mouth to feed. In July 1942, Barbara gave birth to a son, Donald Edward, in the comparative haven of Rodney House, Walton-on-Thames, where her elder two children had been born.\ Although Ted and Barbara marketed themselves as a respectable family couple, they were not yet married. Clearly, Ted Wells had not pursued the issue of divorce until Barbara"s new baby meant the separation was irreparable. On 25 October 1942, he petitioned against her, naming Ted Andrews as co-respondent. It was usual in those days for the woman to petition, but Wells had been too much of a gentleman already. While unmarried mothers in the Second World War were common enough, at thirty-two Barbara was older than most. With no legal commitment from Ted Andrews, she was in a very uncertain position indeed – as was her daughter, who was fast learning the need for self-reliance.\ As if to illustrate the point, the Blitz lit up the skies on a nightly basis. Whenever the sirens moaned, Barbara and "Uncle Ted", with baby Donald and Julie in tow, would dash across to Mornington Crescent station. "Incendiaries were dropping all over the place," Julie told me, "and I do have fairly good memories of going down into the Underground and witnessing some of the scenes that Henry Moore depicted so brilliantly in his graphics of the time."\ Down in the bowels of London, they would sometimes remain all night on the platform with dozens of other Londoners. As the small hours edged towards morning, Ted would entertain the huddled crowd with songs on his guitar. During one air raid, he realised he had left his instrument behind. Before anyone could stop him, he ran out of the shelter, Barbara rushing behind. Julie was left alone in the crowd with baby Donald in his carry-cot, listening to the bombs thundering above, fearing the worst. Then the couple reappeared, the Canadian Troubadour provided songs and a guitar, and Julie buried yet another bad scare – for the time being.\ When Ted and Barbara were out on tour with ENSA, a nanny would look after the two children, sending Julie out to buy packets of cigarettes. The seven-year-old would cadge one and do her best to inhale, remembering, "I"d sneak behind the bathroom door and think I was no end of a clever girl." On other occasions, they would slip into the famous old Bedford Theatre in Camden High Street. The rowdy music-hall atmosphere would be part of Julie"s own life all too soon. In 1942, as the war began to tilt in the Allies" favour, she began classes at the Cone Ripman (later Arts Educational) stage school in Upper Grosvenor Street, Mayfair.\ The following year, Ted and Barbara were at last earning enough to rent a ground-floor flat (with its own basement air-raid shelter) at 29 Clarendon Street, Pimlico. Julie"s mother still registered herself as Barbara Wells, but on 25 November 1943, only three days after her divorce was made final, she and Edward Vernon Andrews were finally married, in Westminster City Register Office. The ceremony was witnessed by Barbara"s sister Joan, herself now married, although her husband, Bill Wilby, was at that time an RAF prisoner-of-war. Joan lived in a small flat nearby, where Julie and Donald stayed whenever ENSA concerts kept their parents out of town.\ Ted and Barbara Andrews were frantically busy, saving as much as they could to buy a home of their own. By the end of 1943, they had scraped together enough to put down a deposit on 15 Cromwell Road, Beckenham, ten miles south-east of central London, on the edge of Kent. Money now also stretched – just – to pay for Julie"s fees at the private Woodbrook Girls" School in Hayne Road, where for two years she received what she would call "some of the best schooling in my life". But even as she became used to this more stable environment, the threat of bombing proved greater than ever, as she would recall: "The doodlebugs began arriving while we lived in Beckenham, and it was terrifying to look up into the sky and see and hear one of those rockets coming down." The droning sound would be followed by a sudden, fearful silence, as the missile plummeted to earth.\ Beckenham lay directly under one of the main air routes into London. "Julie, then eight, would arm herself with a whistle, stand on the mound and keep a look out," said her mother. One day, Julie was staring into the sky so fixedly that she forgot to sound the alert; the flying bomb landed a matter of yards from the house.\ Ted"s guitar sessions in the air-raid shelter were more welcome than ever. And it was beneath the onslaught of the doodlebugs, when a group of neighbours started singing "Strawberry Fair", that one of the most famous voices in the world is said to have been discovered, rising up above all the others. "I ended," said Julie, "an octave higher."\ According to legend, the eight-year-old acted as if nothing unusual had occurred, while Barbara stared in amazement at Ted. Closer attention revealed her range to be truly remarkable, as Barbara noted: "Over three octaves, there was this unbroken line of voice."\ "I sounded like an immature Yma Sumac," Julie told me, referring to the Peruvian soprano with the stratospheric four-octave range. But in the general amazement at the power of her voice, there was one person who was less than surprised: the vast personality who, in Julie"s own words, "thundered across my childhood", Ted Andrews. In fact, it was not long after Barbara had left Ted Wells in Walton-on-Thames that the Canadian Troubadour had first sensed the little girl"s musical gift. Consequently, on an early ENSA tour, he had written a letter that was to have a profound impact on every aspect of Julie"s life.\ Madame Lilian Stiles-Allen was one of Britain"s great sopranos. Famous in the oratorio repertoire, she had performed in Hiawatha at the Royal Albert Hall in the 1920s, Vaughan-Williams" Serenade to Music in 1938 and over a thousand BBC broadcasts. Her music master once described her as having "a throat of gold . . . her speaking voice and her singing voice are so much alike". They were words that might equally have applied to Lilian Stiles-Allen"s own most famous pupil.\ A highly gifted teacher, Madame had given lessons to Ted Andrews a few years earlier, and had, she said, "saved his voice". She abhorred the practice of singing on the open vowel. "I call that gargling. I will have perfect diction . . . In the Bible, it says, "In the beginning was the Word." I thought, if it"s enough for God, it"s enough for me."\ Replying to Ted"s letter, Madame agreed to hear Julie sing. But bombing forced the retired opera singer to leave London and move more than two hundred miles north to Yorkshire, making her home in a beautiful seventeenth-century farm house in Headingley, just outside Leeds. It was not until 1943 that Ted was finally to take Julie to meet her prospective singing teacher.\ Madame Stiles-Allen died in 1982, aged ninety-one. She left behind a personal memoir, Julie Andrews – My Star Pupil, in which she vividly recalled the first of many meetings with the seven-year-old prodigy:\ Julie was then the plainest child imaginable. She wore a brace for her buck teeth, and she had a slight cast in her right eye and two flying pigtails. Her parents could not really afford the expense of lessons, but that did not matter. Even then, as a skinny seven-year-old, she had a special magic. She radiated personality.\ In my big book-lined music room with the piano in the corner she sang for me, unaccompanied, Waldteufel"s "Skater"s Waltz". She sang it beautifully, but I felt she was rather young to begin lessons or to concentrate on the work I should want to give her. "Thank you, Julie; that was lovely," I said. Then, when she had left the room, I told Ted, "Let her play with her toys and dolls for the present. But bring her here again."\ "Oh gosh," Julie told me. "The early years were such a mixture of pain and joy. I wasn"t very happy. It was hard for me to embrace my stepfather because I still adored my dad. I felt that I would be disloyal to him if I cared too much about performing. I began studying when I was about seven or eight with my stepfather. It was an effort to get close to me that made him start giving me singing lessons."\ Despite her hostility, Julie would grudgingly follow Ted into the piano room, and listen as he taught. But when it came to practical demonstration, she turned to stone. He was asking her to feel his back as he breathed into it. There seemed nothing untoward about this – except that she could not bear the idea of touching him. "I just stood there, silently defying him," she later said. But Ted, for all his brashness, genuinely wanted to make her understand the importance of technique. "Come on now, Julie," he coaxed. "If you don"t want to do it for me, do it for Mummy." Sensing that he spoke in good faith, Julie started to learn from his example.\ At the same time, Barbara was determined to correct her daughter"s "lazy" right eye, buying Dr William H. Bates"s manual Better Sight Without Glasses. To Julie, it all seemed a huge bore. It had been one thing singing for fun in the air-raid shelter, quite another having to practise breathing and scales every day – let alone beastly eye exercises. Realising how much she hated the routine, Ted bought Julie The Art of Seeing by Aldous Huxley. Inside the front cover was the message, "Dear Julie, this is for you, and I hope, when we read it together, it will help you. With love from Pop."\ Slowly, Julie began to be more trusting of him. In the summer of 1944, she followed "Pop" and Barbara on tour. Performing in Leeds, Ted remembered Madame Stiles-Allen"s open invitation. The family paid the Old Farm another visit, during which Julie sang again.\ But Madame was still mindful of the dangers in training such a young talent: "I explained these to her parents. I could see that she had a most remarkable voice, already possessing adult power and range. What I feared was that this phenomenon might not last, or that training might do permanent damage to her growing vocal cords." She explained that she would require medical opinion before accepting Julie as a pupil. A series of examinations by throat specialists ensued – and it was then that Ted and Barbara discovered Julie"s secret: she had a fully developed adult larynx. "Yes," said Madame, finally convinced. "I will take her."\ With the end of the war in 1945, Ted and Barbara Andrews transferred their act from ENSA to the music halls. But money was still tight. Madame Stiles-Allen agreed to let them pay for the lessons when they could afford it, a mark of faith in her newest pupil.\ Twice a month, Julie now faced the alarming prospect of making the long train journey on her own. Even when she arrived at Leeds, to be met by Madame"s husband, Sydney Jeffries-Harris ("Uncle Jeff"), her fears were not over. As Madame recalled, Julie was over-sensitive to the Old Farm: "Its long corridors, dimly lit and strangely shadowed by gas brackets, gave her a feeling of eeriness, until she got used to it. The old timbers creaked at night and she began to think the old place was haunted." But soon, Julie came to regard it as a second home; the dreaded train journeys also became less traumatic, building her incipient self-reliance.\ The youngest pupil at the Old Farm, Julie was also the most conscientious. Next to the huge studio, which had once been a hay barn, was the little study where, at nine o"clock each morning, she would be the first at work. "Apart from her singing," said Madame, "I paid a lot of attention to the clarity of her diction, which has always been a fetish of mine. I always made a point with her that singing is musical speech. "They are not two things apart," I told her. "If you can"t hear a singer"s words, it is like a body moving without legs to carry it."\ As classes progressed, Madame saw Julie blossoming.\ Her singing was coming alive; even the exercises were becoming exciting for her. She also had a very keen ear for languages and very quickly learned to sing the aria "Je suis Titania" in fluent French. Yet she had no sophistication, no illusions, no inflated ideas that she was anything outstanding – only a genuine love of singing.\ The range, accuracy and tone of Julie"s voice amazed me. All her life, I discovered, she had possessed the rare gift of absolute pitch. I make it a rule as a singing teacher to get three\ octaves in all voices. Julie, as a little girl and right up to the age of fourteen, had a most unusual four-octave range, from two Cs above Alt. right down to two Cs below middle C. She had absolute confidence in her voice, and in me.\ Above all, Madame impressed on Julie a lesson that would carry her to future triumph: "A voice is a gift, given in trust, given to be used and treated with care. And, in doing so, you yourself will gain great joy."\ Hard work, brightness of delivery, eagerness to please: lessons like these would permanently define Julie"s image. There was another discipline: control over the audience. "You are like a fisherman," said Madame, "you have to get them on a hook."\ "I never had another teacher," Julie said later. "She was wonderful."\ Back at Woodbrook School, the other girls were unimpressed. The budding prodigy still had bandy legs and a face covered in freckles – still needed a tooth brace and eye exercises. "I was", she told me over fifty years later, "a pretty hideous child." She was particularly aware that, unlike her friends, she did not have a regulated home life. One week she would be boating on the Thames with her father; the next, she would be out on tour with Ted and Barbara Andrews, by now well-known entertainers on the wireless as well as on stage.\ The bond between mother and daughter remained very close. But, in late 1945, Barbara found herself pregnant with her fourth child. Self-conscious in all but her singing, Julie desperately wanted to retain her "very important privilege", to be the only girl in the family – even though she knew that Barbara wanted another daughter. "Please God," she prayed hard each night, "let the new baby be a boy." In May 1946, a boy, Christopher Stuart, was born, and Julie felt a rush of remorse – the desperate insecurity of a young girl still craving for the certainty of love.\ Soon after Christopher was born, the family moved back to Waltonon- Thames, where Ted and Barbara had bought a rambling, five-bedroom house on West Grove. It was called The Old Meuse. There, for the rest of Julie"s childhood, they were to remain.\ Madame Stiles-Allen also moved, to Kent. She now taught from a cottage in the village of West Kingsdown, where Julie resumed her training, on more than one occasion giving a recital at the local hall. Madame would eventually hand over the Old Farm to the Yorkshire College of Music and Drama, where the hay barn in which she taught Julie Andrews to sing remains the principal studio to this day.\ Julie seemed ready to try her wings professionally. Further training at RADA, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, was considered; instead, as Barbara later explained, "We decided that a little toughening up as far as the theatre world was concerned would be good, and so we took Julie into our act. Let"s face it – it didn"t hurt the act either." With hindsight, RADA would have stood Julie in good stead for the huge challenges that lay ahead. Financial necessity, however, put practice ahead of theory; but despite the delight she had known in Madame"s lessons, little Julia Wells was mortified by the idea of performing with Ted Andrews.\ "I loathed singing, and resented my stepfather. He embarrassed and upset me by asking me to perform." So would Julie remember her professional beginnings, supporting Ted and Barbara Andrews in the immediate post-war years. "It must have been ghastly, but it went down all right," she said. "They performed by the sea; underneath the times of the performances would be written "weather and tide permitting"."\ Excerpted from Julie Andrews by Richard Stirling.Copyright © 2007 by Richard Stirling.Published in May 2009 by St. Martin"s Press.\ All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.\ \ \ Continues...\ \ \ \ Excerpted from Julie Andrews by Stirling, Richard Copyright © 2008 by Stirling, Richard. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

\ Publishers WeeklyLondon-based stage/TV/film actor Stirling brings up the house lights to detail the entire life of the performer he has known since 1986. Having previously written about Andrews for the Evening Standardand other publications, he highlights recollections of her associates, in addition to his extensive archival research, plowing through some six decades of reportage and interviews in magazines, newspapers and books. Stirling grabs the reader's attention on the opening pages with a description of Andrews's 1997 Mount Sinai Hospital throat surgery, a normal operation that went tragically wrong: "Her principal trademark, the voice of mountain spring purity, was gone, as astonishingly as it had first appeared." Beginning with her childhood in London during the Blitz and youthful voice lessons, Stirling traces her career from post-WWII performances on BBC Radio and the London stage to her 1954 arrival in America with The Boy Friend. After acclaim for My Fair Ladyand Camelotcame the caravan of TV and movie roles that continue until the present day with voice work in the Shrek series and last year's Enchanted. The book successfully documents and details the professional and personal peaks of her life. With Andrews's memoir, Home, to be published in April, devoted fans are sure to turn to both. 8-page b&w photo insert not seen by PW. (Apr.)\ Copyright 2007 Reed Business Information\ \