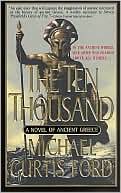

Latro in the Mist: Soldier of the Mist/Soldier of Arete

A distinguished compilation of two classic fantasy novels, Soldier of the Mist and Soldier of Areté, in one volume\ This omnibus of two acclaimed novels is the story of Latro, a Roman mercenary who while fighting in Greece received a head injury that deprived him of his short-term memory but gave him in return the ability to see and converse with the supernatural creatures and the gods and goddesses, who invisibly inhabit the ancient landscape. Latro forgets everything when he sleeps. Writing...

Search in google:

A distinguished compilation of two classic fantasy novels, Soldier of the Mist and Soldier of Areté, in one volumeThis omnibus of two acclaimed novels is the story of Latro, a Roman mercenary who while fighting in Greece received a head injury that deprived him of his short-term memory but gave him in return the ability to see and converse with the supernatural creatures and the gods and goddesses, who invisibly inhabit the ancient landscape. Latro forgets everything when he sleeps. Writing down his experiences every day and reading his journal anew each morning gives him a poignantly tenuous hold on himself, but his story's hold on readers is powerful indeed, and many consider these Wolfe's best books.Publishers WeeklyIn his foreword to Latro in the Mist, which pairs Gene Wolfe's acclaimed historical fantasies Soldier of the Mist (1986) and Soldier of Arete (1989), Wolfe reveals that the two novels are in fact his translations of the diary writings of Latro, a Roman mercenary wounded in battle in ancient Greece. Latro's head wound ruined his short-term memory, but bestowed upon him the gift of conversing with gods and goddesses. Copyright 2003 Reed Business Information.

Latro in the Mist\ SOLDIER OF THE MISTThis book is dedicated with the greatest respect and affection to Herodotos of HalicarnassosFirst there was a struggle at the barricade of shields; then, the barricade down, a bitter and protracted fight, hand to hand, at the temple of Demeter ... .-Herodotos \ \ \ Although this book is fiction, it is based on actual events of 479 B.C.ForewordABOUT TWO YEARS AGO, an urn containing scrolls of papyrus, all apparently unused, was found behind a collection of Roman lyres in the basement of the British Museum. The museum retained the urn and disposed of the scrolls, which were listed in Sotheby's catalogue as Lot 183. Various blank papyrus, rolls, possible the stock of an Egyptian stationer.After passing through several hands, they became the property of Mr. D_______ A_______, a dealer and collector in Detroit. He got the notion that something might be concealed in the sticks on which the papyrus was wound and had them X-rayed. The X-rays showed them to be solid; but they also showed line after line of minute characters on the sheet (technically the protokollon) gummed to each stick. Sensing himself on the verge of a discovery of real bibliotic importance, he examined a scroll under a powerful lens and found that all its sheets were covered on both sides with minute gray writing, which the personnel of the museum, and of Sotheby's, had apparently taken for dust smears. Spectrographic analysis has established that the writing instrument was a sharp "pencil" of metallic lead. Knowing my interest in dead languages, the owner has asked me to provide this translation.With the exception of a short section in passable Greek, this first scroll is written in archaic Latin, without punctuation. The author, who called himself "Latro" (a word that may mean brigand, guerrilla, hired man, bodyguard, or pawn), had a disastrous penchant for abbreviation—indeed, it is rare to find him giving any but the shortest words in full; there is a distinct possibility that some abbreviations have been misread. The reader should keep in mind that all punctuation is mine; I haveadded details merely implied in the text in some instances and have given in full some conversations given in summary.For convenience in reading, I have divided the work into chapters, breaking the text (insofar as possible) at the points at which "Latro" ceased to write. I have employed the first few words of each chapter as its title.In dealing with place names, I have followed the original writer, who sometimes wrote them as he heard them but more often translated them when he understood (or believed he understood) their meanings. "Tower Hill" is probably Corinth; "the Long Coast" is surely Attica. In some cases, Latro was certainly mistaken. He seems to have heard some taciturn person referred to as having Laconic manners (Greek a eµó ) and to have concluded that Laconia meant "the Silent Country." His error in deriving the name of the principal city of that region from a word for rope or cord (Greek sp t ) was one made by many uneducated speakers of his time. He appears to have had some knowledge of Semitic languages and to have spoken Greek fairly fluently, but to have read it poorly or not at all. \ A few words about the culture in which Latro found himself soon after he began to write may be in order. The people no more called themselves Greeks than do the people of the nation we call Greece today. By our standards they were casual about clothes, though in most cities it was considered improper for a woman to appear in public completely naked, as men often did. Breakfast was not eaten; unless he had been drinking the night before, the average Greek rose at dawn and ate his first meal at noon; a second meal was eaten in the evening. In peacetime even children drank diluted wine; in wartime soldiers complained bitterly because they had only water, and often fell ill.Athens ("Thought") was more crime-ridden than New York. Its law against women's leaving their homes alone was meant to prevent attacks on them. (Another woman or even a child was a satisfactory escort.) First-floor rooms were windowless, and burglars were called "wallbreakers." Despite the modern myth, exclusive homosexuality was rare and generally condemned, although bisexuality was common and accepted. The Athenian police were barbarian mercenaries, employedbecause they were more difficult to corrupt than Greeks. Their skill with the bow was often valuable in apprehending suspects.Although the Greek city-states were more diverse in law and custom than most scholars are willing to admit, a brisk trade in goods had effected some standardization in money and units of measure. An obol, vulgarly called a spit, bought a light meal. The oarsmen on warships were paid two or three obols a day, but of course they were fed from their ship's stores. Six obols made a drachma (a handful), and a drachma bought a day's service from a skilled mercenary (who supplied his own equipment) or a night's service from one of Kalleos's women. A gold stator was worth two silver drachmas. The most widely circulated tendrachma coin was called an owl, from the image on its reverse. A hundred drachmas made a mina; sixty minas a talent—about fifty-seven pounds of gold or eight hundred pounds of silver.The talent was also a unit of weight: about fifty-seven pounds. The most commonly used measure of distance was the stade, from which comes our stadium. A stade was about two hundred yards, or a little over one-tenth of a mile.Humanitarians accepted the institution of slavery, realizing that the alternative was massacre; we who have seen the holocaust of the European Jews should be sparing in our reproaches. Prisoners of war were a principal source of supply. A really first-class slave might cost as much as ten minas, the equivalent of thirty-six thousand dollars. Most were much more reasonable.If the average well-read American were asked to name five famous Greeks, he would probably answer, "Homer, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Pericles." Critics of Latro's account would do well to recall that Homer had been dead for four hundred years at the time Latro wrote, and that no one had heard of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, or Pericles. The word philosopher was not yet in use.In ancient Greece, skeptics were those who thought, not those who scoffed. Modern skeptics should note that Latro reports Greece as it was reported by the Greeks themselves. The runner sent from Athens to ask Spartan help before the battle of Marathon met the god Pan on the road and conscientiously recounted their conversation to the Athenian Assemblywhen he returned. (The Spartans, who well knew who ruled their land, refused to march before the full of the moon.) \ —G.W.PART ONEONERead This Each DayI WRITE OF WHAT has just occurred. The healer came into this tent at dawn and asked whether I recalled him. When I said I did not, he explained. He gave me this scroll, with this stylus of the slingstone metal, which marks it as though it were wax.My name is Latro. I must not forget. The healer said I forget very quickly, and that is because of a wound I suffered in a battle. He named it as though it were a man, but I do not remember the name. He said I must learn to write down as much as I can, so I can read it when I have forgotten. Thus he has given me this scroll and this stylus of heavy slingstone metal.I wrote something for him in the dust first. He seemed pleased I could write, saying most soldiers cannot. He said also that my letters are well formed, though some are of shapes he does not know. I held the lamp, and he showed me his writing. It seemed very strange to me. He is of Riverland.He asked me my name, but I could not bring it to my lips. He asked if I remembered speaking to him yesterday, and I did not. He has spoken to me several times, he says, but I have always forgotten when he comes again. He said some other soldiers told him my name, "Latro," and he asked if I could remember my home. I could. I told him of our house and the brook that laughs over colored stones. I described Mother and Father to him, just as I see them in my mind, but when he asked their names, I could tell him only "Mother" and "Father." He said he thought these memories very old, perhaps from twenty years past or more. He asked who taught me to write, but I could not tell him. Then he gave me these things.I am sitting by the flap, and because I have written all I rememberof what he said, I will write what I see, so that perhaps in time to come I can sift my writing for what may be of value to me.The sky is wide and blue, though the sun is not yet higher than the tents. There are many, many tents. Some are of hides, some of cloth. Most are plain, but I see one hung with tassels of bright wool. Soon after the healer left, four stiff-legged, unwilling camels were driven past by shouting men. Just now they returned,laden and hung with red and blue tassels of the same kind and raising a great dust because their drivers beat them to make them run.Soldiers hurry by me, sometimes running, never smiling. Most are short, strong men with black beards. They wear trousers, and embroidered tunics of turquoise and gold over corselets of scales. One came carrying a spear with an apple of gold. He was the first to meet my eyes, and so I stopped him and asked whose army this is. He said, "The Great King's," then made me sit once more and hurried off.My head still gives me pain. Often my fingers stray toward the bandages there, though the healer said not to touch them. I keep this stylus in my hand, and I will not. Sometimes it seems to me that there is a mist before my eyes that the sun cannot drive away.Now I write again. I have been examining the sword and armor piled beside my couch. There is a helmet, holed where I received my wound. There is Falcata too, and there are plates for the breast and back. I took up Falcata, and though I did not know her, she knew my hand. Some of the other wounded looked afraid, so I sheathed her again. They do not understand my speech, nor I theirs.The healer came after I wrote last, and I asked him where I had been hurt. He said it was near the shrine of the Earth Mother, where the Great King's army fought the army of Thought and the Rope Makers.I helped take down our tent. There are mules for the litters of those who cannot walk. He said I must keep with the rest; if I become separated, I must look for his own mule, who is piebald, or for his servant, who has but one eye. That is the man who carries out the dead, I think. I told him I would carry this scroll and wear the round plates and my sword on my belt of manhood. My helmet might be sold for its bronze, but I do not want to carry it. They have loaded it with the bedding. \ \ We rest beside a river, and I write with my feet cooling in its stream. I do not know the name of this river. The army of the Great King blackens the road for many miles, and I, having seen it, do not understand how it could have been vanquished—or why I joined it, since where there are so many men no one could count them, one more or less is nothing. It is said our enemies pursue us, and our cavalry keeps them at bay. This I overheard when I saw a party of horsemen hurrying to the rear. The men who said it speak as I to the healer, and not in these words I write.A black man is with me. He wears the skin of a spotted beast, and his spear is tipped with twisted horn. Sometimes he speaks, but if ever I knew his words, I have forgotten them all. When we met, he asked by signs if I had seen such men as he. I shook my head, and he seemed to understand. He peers at these letters I make with great interest.The river was muddy for a time after so many had drunk. Now it runs clear again, and I see myself and the black man reflected. I am not as he, nor as the Great King's other soldiers. I pointed to my arm and my hair and asked the black man if he had seen another such as I. He nodded and opened two little bags he carries; there is white paste in one and vermilion in the other. He showed me by signs that we should go with the others; as he did, I saw beyond his shoulder another man, whiter than I, in the river. At first I thought him drowned, for his face was beneath the water; but he smiled and waved to me, pointing up the river, where the Great King's army marches, before he vanished swiftly downstream. I have told the black man I will not go, because I wish to write of this river-man while I can.His skin was white as foam, his beard black and curling, so that for a moment I thought it spun of the silt. He was thick at the waist, like a rich man among the veterans, but thick of muscle, too, and horned like a bull. His eyes were merry and brave, the eyes that say, "I will knock down the tower." When he gestured, it seemed to me he meant we would meet again, and I do not want to forget him. His river is cold and smooth, racing from the hills to water this land. I will drink again, and the black man and I will go. \ Evening. The healer would feed me if I could find him, I know; but I am too tired to walk far. As the day passed, I grew weaker and couldwalk only slowly. When the black man tried to hurry me, I signed that he should go forward alone. He shook his head and I think called me many vile names; and at last flourished his spear as if to strike me with the shaft. I drew Falcata. He dropped his spear and with his chin (so he points) told me to look behind us. There under the staring sun a thousand horsemen scoured the plain, their shadows and the clouds of dust more visible than the riders. A soldier with a wounded leg, who could walk even less than I, said the slingers and archers with whom they warred were the slaves of the Rope Makers, and if someone he named were still in the country of the sun, we would turn and rend them. Yet he seemed to fear the Rope Makers.Now the black man has built a fire and gone among the tents to look for food. I feel it can bring me no strength and I shall die tomorrow, not at the hands of those slaves but falling suddenly and embracing the earth, drawing it over me like a cloak. The soldiers I can understand talk much of gods, cursing them and cursing others—ourselves more than once—in their names. It seems to me I once knew gods, worshiping beside Mother where the vines twined about the house of some small god. Now his name is lost. Even if I could call on him, I do not think he could come at my bidding. This land is surely far, very far from his little house. \ I have gathered wood and heaped it on our fire to make light so I can write. For I must never forget what happened, never. Yet the mist will come, and it will be lost until I read what I now write.I went to the river and said, "I know no god but you. I die tomorrow, and I will sink into the earth with the other dead. But I pray you will give good fortune always to the black man, who has been more than a brother to me. Here is my sword, with her I would have slain him. Accept the sacrifice!" Then I cast Falcata into the water.At once the river-man appeared, rising from the dark stream and toying with my sword, tossing her in his hands and catching her again, sometimes by the hilt, sometimes by the blade. With him were two girls who might have been his daughters, and while he teased them with her, they sought to snatch her from him. All three shone like pearls in the moonlight.Soon he cast Falcata at my feet. "I would mend you if I could," hesaid to me. "That lies beyond me, though steel and wood, fish, wheat, and barley all obey me." His voice was like the rushing of great waters. "My power is but this: that what is given to me I return manyfold. Thus I cast your sickle on my shore again, new-tempered in my flood. Not wood, nor bronze, nor iron shall stand against her, and she will not fail you until you fail her."So saying, he and his daughters, if such they were, sank into the water again. I took up Falcata, thinking to dry her blade; but she was hot and dry. Then the black man returned with bread and meat, and many tales told with his fingers of how he had stolen them. We ate, and now he sleeps.TWOAt HillWE HAVE CAMPED, AND I have forgotten much of what happened since I saw the Swift God. Indeed, I have forgotten the seeing and know of it only because I have read it in this scroll in which I write.Hill is very beautiful. There are buildings of marble, and a wonderful market. The people are frightened, however, and angry with the Great King because he is not here with more of his soldiers. They fought for him, thinking he would surely best the armies of Thought and Rope—this though the people of those cities are sons of Hellen just as they themselves are. They say the people of Thought hate their very name and will sweep their streets with fire, even as the Great King swept the streets of Thought. They say (for I listened to them in the market) that they will throw themselves upon the mercy of the Rope Makers, but that the Rope Makers have no mercy. They wish us to remain, but they say we will soon go, leaving them no protection but their walls and their own men, of whom the best, their Sacred Band, are all dead. And I think they speak the truth, for already I have heard some say we will break our camp tomorrow.There are many inns here, but the black man and I have no money, so we sleep outside the walls with the other soldiers of the Great King. I wish I had described the healer when I first wrote, for I cannot find him among so many. There are many piebald mules and not a few one-eyed men, but none of the one-eyed men will say he is the servant of the healer. Most will not speak with me; seeing my bandages, they think I have come to beg. I will not beg, yet it seems to me less honorable to eat what the black man takes, as I just did. This morning I tried to takefood in the market as he does, but he is more skilled than I. Soon we will go to another market, where I will stand between him and the owners of the stalls as I did this morning. It is hard for him, because the people stare; yet he is very clever and often succeeds even when they watch him. I do not know how, because he has shown me many times that I am never to watch. \ While the black man speaks with his hands and the rest argue, I write these words in the temple of the Shining God, which stands in the agora, the great market of Hill. So much has happened since I last wrote—and I have so little notion of what it may mean—that I do not know how I should begin.The black man and I went to a different market after we had eaten the first meal and rested, to the agora, in the center of the city. Here jewelry and gold and silver cups are sold, and not just bread and wine, fish and figs. There are many fine buildings with pillars of marble; and there is a floor of stone over the earth, as though one stood in such a building already.In the midst of all this and the thronging buyers and sellers, there is a fountain, and in the midst of the fountain, pouring forth its waters, an image of the Swift God worked in marble.Having read of him in this scroll, I rushed to it, thinking the image to be the Swift God himself and calling out to him. A hundred people at least crowded around us then, some soldiers of the Great King like ourselves, but most citizens of Hill. They shouted many questions, and I answered as well as I could. The black man came too, asking by signs for money. Copper, bronze, and silver rained into his hands, so many coins that he had to stop at last and put them into the bag in which he carries his possessions.That had a bad effect, and little more was given; but men with many rings came and said I must go to the House of the Sun, and when the black man said we would not, said the Sun is the healer and called upon some soldiers of Hill to help them.Thus we were taken into one of the finest buildings, with columns and many wide steps, where I was made to kneel before the prophetess, who sat upon a bronze tripod. There was much talk between the menwith rings and a lean priest, who said many times and in many different ways that the prophetess would not speak for their god until an offering was made.At last one of the men with many rings sent his slave away, and when we had waited longer still, and all the men with many rings had spoken of the gods and what they knew of them, and what their fathers and grandfathers and uncles had told them of them, this slave returned, bringing with him a little slave girl no taller than my waist.Then her owner spoke of her most highly, pointing to her comely face and swearing she could read and that she had never known a man. I wondered to hear it, for from the looks she gave the slave who had brought her she knew him and did not like him; but I soon saw the lean priest believed the man with many rings hardly more than I, and perhaps less.When he had heard him out, he drew the slave girl to one side and showed her letters cut in the walls. These were not all such letters as I make now, and yet I saw they were writing indeed. "Read me the words of the god who makes the future plain, child," the lean priest commanded her. "Read aloud of the god who heals and lets fly the swift arrows of death."Smoothly and skillfully the slave girl read:"Here Leto's son, who strikes the lyre Makes clear our days with golden fire, Heals all wounds, gives hope divine, To those who kneel at his shrine."Her voice was clear and sweet, and though it was not like the shouting on the drill field, it seemed to rise above the clamor of the marketplace outside.The priest nodded with satisfaction, motioned the little slave girl to silence, and nodded to the prophetess, who was at once seized by the god they served, so that she writhed and shrieked upon her tripod.Soon her screams stopped, and she began to speak as quickly as the rattling of pebbles in a jar, in a voice like no woman's; but I paid little heed to her because my eyes were on a golden man, larger than any man should be, who had stepped silently from an alcove.He motioned to me, and I came.He was young and formed like a soldier, but he bore no scars. A bow and a shepherd's staff, both of gold, were clasped in his left hand, and a quiver of golden arrows was slung upon his back. He crouched before me as I might have crouched to speak with a child.I bowed, and as I did I looked around at the others; they heard the prophetess in attitudes of reverence and did not see the golden giant."For them I am not here," he said, answering a question I had not asked. His words were fair and smooth, like those of a seller who tells his customer that his goods have been reserved for him alone."How can that be?" Even as he spoke, the others murmured and nodded, their eyes still on the prophetess."Only the solitary may see the gods," the giant told me. "For the rest, every god is the Unknown God." "Am I alone then?" I asked him."Do you behold me?"I nodded."Prayers to me are sometimes granted," he said. "You have come with no petition. Have you one to make now?"Unable to speak or think, I shook my head."Then you shall have such gifts as are mine to give. Hear my attributes : I am a god of divination, of music, of death, and of healing; I am the slayer of wolves and the master of the sun. I prophesy that though you will wander far in search of your home, you will not find it until you are farthest from it. Once only, you will sing as men sang in the Age of Gold to the playing of the gods. Long after, you will find what you seek in the dead city."Though healing is mine, I cannot heal you, nor would I if I could; by the shrine of the Great Mother you fell, to a shrine of hers you must return. Then she will point the way, and in the end the wolf's tooth will return to her who sent it."Even as this golden man spoke he grew dim in my sight, as though all his substance were being drawn again into the alcove from which he had stepped only a moment before."Look beneath the sun ... ."When he was gone I rose, dusting my chiton with my hands. The black man, the lean priest, the men with many rings, and even the childstill stood before the prophetess; but now the men with many rings argued among themselves, some pointing to the youngest of their number, who spoke at length with outspread hands.When he had finished, the others spoke all together, many telling him how fortunate he was, because he would leave the city; whereupon he began once more. I soon grew tired of hearing him and read what is written here instead, then wrote as I write now—while still they argue, the black man talks of money with his hands, and the youngest of the men with many rings (who is not truly young, for the hair is leaving his head on both sides) backs away as if to fly.The child looks at me, at him, at the black man, and then at me once more, with wondering eyes.THREEIoTHE SLAVE GIRL WOKE ME before the first light. Our fire was nearly out, and she was breaking sticks across her knee to add to it. "I'm sorry, master," she said. "I tried to do it as quietly as I could."I felt I knew her, but I could not recall the time or place where we had met. I asked who she was."Io. It means io—'happiness'—master." "And who am I?""You're Latro the soldier, master."She had thrice called me "master." I asked, "Are you a slave, then, Io?" The truth was that I had assumed it already from her tattered peplos."I'm your slave, master. The god gave me to you yesterday. Don't you remember?"I told her I did not."They took me to the god's house because he wouldn't tell them anything till somebody brought a present. I was the present, and for me he seized the priestess so she just about went crazy. She said I belonged to you, and I should go with you wherever you went."A man who had rolled himself in a fine blue cloak threw it off and sat up at that. "Not that I recall," he said. "And I was there." "This was afterward," Io declared. "After you and the others had left."He glanced at her skeptically, then said, "I hope you haven't forgotten me as well, Latro." When he saw I had, he continued, "My name is Pindaros, sir, son of Pagondas; and I am a poet. I was one of those who carried you to the temple of our patron."I said, "I feel I've been dreaming and have just awakened; but Ican't tell you what my dream was, or what preceded it." "Ah!" Reaching in his traveling bag, Pindaros produced a waxed tablet and stylus. "That's really rather good. I hope you won't mind if I write it down? I might be able to make use of it somewhere." "Write it down?" Something stirred in me, though I could not see it clearly."Yes, so I won't forget. You do the same thing, Latro. Yesterday you showed me your book. Do you still have it?"I looked about and saw this scroll lying where I had slept, with the stylus thrust through the cords."It's a good thing you didn't knock it into the fire," Pindaros remarked."I wish I had a cloak like yours." "Why, then, I'll buy you one. I've a little money, having had the good fortune to inherit a bit of land two years ago. Or your friend there can. He collected quite a tidy sum before we took you to the House of the God."I looked at the black man to whom Pindaros pointed. He was still asleep, or feigning to be; but he would not sleep much longer: even as I looked, horns brayed far off. All around us men were stirring into wakefulness."Whose army is this?" I asked."What? You a soldier in it, and you don't know your strategist?"I shook my head. "Perhaps I did, once. I no longer remember."Io said, "He forgets because of what they did to him in that battle south of the city." "Well, it used to be Mardonius's, but he's dead; I'm not sure who commands now. Artabazus, I think. At least, he seems to be in charge."I had picked up my scroll. "Perhaps if I read this, I'd remember." "Perhaps you would," Pindaros agreed. "But wait a moment, and you'll have more light. The sun will be up, and we'll have a grand view across Lake Copais there."I was thirsty, so I asked if that was where we were going."To the morning sun? I suppose that's where this army's going, if Pausanius and his Rope Makers have anything to say about it. Farther, perhaps. But you and I are going to the cave of the Earth Goddess. You don't remember what the sibyl said?" "I do," Io announced."You recite it for him, then." Pindaros sighed. "I have a temperamental aversion to bad verse."The slave girl drew herself up to her full height, which was small enough, and chanted:"Look under the sun, if you would see! Sing! Make sacrifice to me! But you must cross the narrow sea. The wolf that howls has wrought you woe! To that dog's mistress you must go! Her hearth burns in the room below. I send you to the God Unseen! Whose temple lies in Death's terrene! There you shall learn why He's not seen. Sing then, and make the hills resound! King, nymph, and priest shall gather round! Wolf, faun, and nymph, spellbound."Pindar shook his head in dismay. "Isn't that the most awful doggerel you ever heard? They do it much better at the Navel of the World, believe me. This may sound like vanity, but I've often thought the sheer badness of the oracle in our shining city was meant as an admonition to me. 'See, Pindaros,' the god is saying, 'what happens when divine poetry is passed through a heart of clay.' Still, it's certainly clear enough, and you can't always say that when the god speaks at the Navel of the World. Half the time he could mean anything." "Do you understand it?" I asked in wonder."Of course. Most of it, at least. Very likely even this child does."Io shook her head. "I wasn't listening when the priest explained." "Actually," Pindaros told her, "I provided more of the explanation than he did, thus drawing this trip upon myself; people suppose that poets have all of time at their disposal, a sort of endless summer."I said, "I feel I have none, or only today. Then it will be gone." "Yes, I suppose you do. And I'll have to interpret the god again for you tomorrow."I shook my head. "I'll write it down." "Of course. I'd forgotten about your book. Very well then. The first phrase is 'Look under the sun, if you would see.' Do you understand that?""I suppose it means I should read my scroll. That's best done by daylight, as you pointed out to me a moment ago." "No, no! When sun appears in the utterances of the sibyl, it always refers to the god. So that phrase means that the light of understanding comes from him; it's one of his best-known faculties. The next, 'Sing! Make sacrifice to me!' means that you are to please him if you wish for understanding. He's the god of music and poetry, so everyone who writes or recites poetry, for example, thereby sacrifices to him; he only accepts rams and rubbish of that sort from boors and the bourgeois, who have nothing better to offer him. Your sacrifice is to be song, and it would be well for you to keep that in mind."I told him I would try."Then there's 'But you must cross the narrow sea.' He's an eastern god, having come to us from the Tall Cap Country, and he's symbolized by the rising sun. Thus that's where you're to make your sacrifice."I nodded, feeling relieved that I would not have to sing at once."On to the next stanza. 'The wolf that howls has wrought you woe!' The god informs us that you've been injured by one whose symbol is the wolf, and points out that the wolf is one of nature's singers—thus the form of your sacrifice, if you are to be healed. 'To that dog's mistress you must go!' Aha!"Pindaros pointed a finger dramatically at the sky. "Here, in my humble opinion, is the single most significant line in the whole business. It is a goddess who has injured you—a goddess whose symbol is the wolf. That can only be the Great Mother, whom we worship under so many names, most of which mean mother, or earth, or grain-giver, or something of that sort. Furthermore, you are to visit a temple or shrine of hers. But there are many such shrines—which is it? Very conveniently the god tells us: 'Her hearth burns in the room below.' That can only be the famous oracle at Lebadeia, not far from here, which is in a cavern. Furthermore, since we wouldn't want to use the coast road with the ships of Thought prowling the Gulf, it lies on the safest road to the Empire and the Tall Cap Country, which clinches it. You must go there and beg her forgiveness for the injury you did her that caused her toinjure you. Only when you've done that will the god be able to cure you—otherwise he would make an enemy of her by doing so, which he understandably doesn't want." "What about the next line?" I asked. "Who is the God Unseen?"Pindaros shook his head. "That I can't tell you. There was a shrine to the Unknown God in Thought, and that's surely Death's Country now that the army's destroyed everything again. But let's wait and see. Very often in these affairs, you have to complete the first step before you really understand the next. My guess is that when you've visited the Great Mother in Trophonius's Cave, everything will be clear. Not that it's possible for a mortal—"Io shouted, "Look down there!" her child's voice so shrill that the black man sat bolt upright. She was shielding her eyes against the sun, which was now rising above the lake. I rose to look, and many of the other soldiers stopped what they were doing to follow the direction of her eyes, so that our part at least of the whole great encampment fell silent.Music came, very faintly, from the shores of the lake, and a hundred people or more capered there in a wild dance. Goats were scattered among them, and these skipped like the dancers, made nervous, perhaps, by two tame panthers."It's the Kid," Pindaros whispered, and he motioned for me to come with him.Io caught my hand as we joined the stream of soldiers going to the lake for water. "Are we invited to their party?"I told her I did not know.Over his shoulder Pindaros said, "You're on a pilgrimage. It wouldn't do to offend him."And so we trooped down the gentle hillside to the lake shore through sweet spring grass and blooming flowers, Pindaros leading, Io clasping my hand, and the black man scowling as he followed some distance behind us. The rising sun had turned the lake to a sheet of gold, and the dawn wind cast aside her dark garments and decked herself in a hundred perfumes. Behind us, the trumpets of the Great King's army sounded again, but though many of the soldiers hurried back to follow them, we did not."You look happy, master," Io said, turning her little face up to mine."I am," I told her. "Aren't you?" "If you are. Oh, yes!""You said you were brought to the god's house as an offering. Weren't you happy there?" "I was afraid," she admitted. "Afraid they'd cut my neck like they do the poor animals, and today I've been afraid the god sent me to you to be a sacrifice someplace else. Do they kill little children for this Great Mother the poet is taking us to see?" "I've no idea, Io; but if they do, I won't let them kill you. No matter how I may have injured her, nothing could justify such a sacrifice.""But suppose you have to do it to find your home and your friends?" "Was it because I wanted to find those things so much that I came to the god's house?""I don't know," Io said pensively. "My old master and some other men made you come, I think. Anyway, you were there when the steward brought me. But we sat together for a little while, and you talked to me about them."Her eyes left mine for the line of celebrants that traced the shore. "Latro, look at them dance!"I did. They leap and whirl, splashing in the shallows, watering the grass with their flying feet and with the wine they drink and pour out even as they dance. The shrilling of the syrinx and the insistent thudding of the tympanon seem louder now. Though masked men leap among them, the dancers are mostly young women, naked or nearly so save for their wild, disordered hair.Io has joined them, and with her the black man and Pindaros, but I watch only little Io. How gay she is with the vine crown twined round her head, and yet how intent on imitating the frenzy of the hebetic girls, the nation of children left far behind her for so long as the dance lasts.Pindaros and the black man and I have left it forever, though once long ago it must have been friends and home to them. As for me—though I have left it too, it seems near; and it holds the only home and the only friends I can remember.FOURA wakened by MoonlightI TRIED TO READ this scroll; but though the moon shone so brightly that my hand cast a sharp shadow on the pale papyrus, I could not make out the shadowy letters. A woman slept beside me, naked as I, and like me wet with dew. I saw her shiver, the swelling of her thigh and the curve of her hip more lovely than I would have thought anything could be; and yet she did not wake.I looked about for something with which to cover her, for it seemed to me that we two would surely not have thrown ourselves upon the grass, thus to sleep with no covering where so many others slept too. My manhood had risen at the sight of—oh!—her. I was ashamed by it, so that I wished a covering for myself, also, but there was nothing.Water glimmered not far off. I went to wash myself, feeling that I had just started from a dream, and that if only I could cool my face I would recall who the woman was and how I came to lie upon the grassy bank with her.I waded out until the water was higher than my waist; it was warmer than the dew and made me feel I was drawing a blanket about me. Splashing my face, I discovered that my head was swathed in cloth. I tried to pull these wrappings away, but the effort seared like a brand, so that I desisted at once.Whether it was the water or the pain that awakened me a second time I cannot say, but I found that though the dreams I had half recalled were gone, nothing replaced them. The murmuring water lapped my chest. Above, the moon shone like a white lamp hung to guide some virgin home, and when I looked toward the bank again I saw her, as pure as the moonlight, a bow bent like the increscent moon in her hand and arrows thrust through the cestus at her waist. For a long while, shepicked her way among the sleepers on the bank. At last she mounted the hill beyond, and at its very summit vanished.Now came the sun, striking diamonds from the opalescent crest of each little wave. It seemed to me I saw it as I had seen it rise across the lake before (for I could see by daylight that the water was indeed a lake), though I could not say when. Since then I have read parts of this scroll, and I understand that better.Even as the moon had awakened me, the sunlight seemed to rouse the rest, who stood and yawned and looked about. I waded back to the bank then, sorry I had stayed to watch the virgin with the bow and not sought farther for some covering for the woman who had slept with me. She slept still, and I cast the shards of the broken wine jar that lay beside her into the lake. Beside this scroll, I discovered a chiton among weapons and armor I felt were mine, and I covered the woman with it.A grave man of forty years or so asked me if I was of his nation, and when I denied it, said, "But you are no barbarian—you speak our tongue." He was as naked as I, but he had a crown of ivy in place of my own head wrappings; he held a slender staff of pine, tipped with a pinecone."Your speech is clear to me," I said. "But I cannot tell you how it came to be so. I ... am here. That is all I know."A child who had been listening said, "He does not remember. He is my master, priest." "Ah!" The priest nodded to himself. "So it is with many. The God in the Tree wipes clean their minds. There is no guilt." "I don't think it was your god," the child told him solemnly. "I think it was the Great Mother, or maybe the Earth Mother or the Pig Lady." "They are the same, my dear," the priest told her kindly. "Come and sit down. You are not too young to understand." He seated himself on the grass. At his gesture, the child sat before him, and I beside her."By your accent, you are from our seven-gated city of Hill, are you not?"She nodded."Think then of such a man as you must often have seen in the city. He is a potter, we will say. He is also the father of a daughter much like yourself, the husband of such a woman as you shall be, and the sonof another. When our men march to war, he takes up his helmet, his hoplon, and his spear; he is a shieldman. Now answer this riddle for me. Which is he? Shieldman, son, husband, father, or potter?" "He's all of them," the child said."Then how will you address him when you speak to him? Assuming you do not know his name?"The child was silent."You will address him according to the place in which you and he find yourselves and the need you have for him, will you not? If you meet him on the drill field, you will say, 'Shieldman.' In his shop, you will say, 'Potter, how much for this dish?'"You see, my dear, there are many gods, but not so many as ignorant people suppose. So with your goddess, whom you call the Lady of the Swine. When we wish her to bless our fields, we call her the Grain Goddess. But when we think of her as the mother of all the things that spring from the soil, trees as well as barley, wild beasts as well as tame, Great Mother."The child said, "I think they ought to tell us their names." "They have many. That is one of the things I would like to teach you, if I can. Were you to go to Riverland, as I went once, you would find the Great Mother there, though the People of the River do not speak of her as we do. A god—or a goddess—must have a name suitable for the tongue of each nation.""The poet said your god was the Kid," the child told him."There you have a perfect example." The priest smiled. "This poet of whom you speak called him the Kid when he spoke to you, and was quite correct to do so. A moment ago, I myself called him the God in the Tree, which is also correct—Why this is extraordinary! Most extraordinary!"Turning to look where he did, I saw a man as black as the night coming toward us. He was as naked as we, but he carried a spear tipped with twisted horn."As I have often told the maenads and satyrs of his train, such rites as we performed yesterday bring the god nearer. Now here is such proof as to be almost miraculous. Come and sit with us, my friend."The black man squatted and feigned to drink."He wants more wine," the child said."He does not speak our tongue?" "I think he understands a little, but he never says anything. Probably somebody laughed once when he tried."The priest smiled again. "You are wise beyond your years, my dear. My friend, we have no more wine. What we had was drunk last night to the honor of the god, or poured out in libations. If you wish to drink this morning, your drink must be of water." He cupped his hand and turned it over as if pouring wine onto the ground, then pointed to the lake.The black man nodded to show he understood but remained where he was."I was about to say," the priest continued, "when the unfathomable powers of the god produced our friend as an illustration, that our god is commonly called the King from Nysa. Do you, either of you, know where Nysa lies?"The child and I admitted we did not."It is in the country of the black men, up the river of Riverland. Our god was conceived when the Descender noticed in his travels a certain Semele, a princess, daughter of the king of our own seven-gated city. We were a monarchy in those days, you see." He cleared his throat. "The Descender disguised himself as a king merely earthly, and visiting her father's palace as a royal guest won her, though they did not wed."The child shook her head sadly."Alas, his wife Teleia learned of it. Some say, by the by, that Teleia is also the Earth Mother and the Great Mother; though I believe that to be an error. Whether I am correct or not, Teleia disguised herself also, putting on the form of a certain old woman who had been the princess's nurse. 'Your lover is of a state more than earthly,' she told Princess Semele. 'Make him promise to reveal—'"A handsome man somewhat younger than the priest had joined us, bringing with him a woman whose hair was dark like other women's, but whose eyes were like two violets. The man said, "I don't suppose you remember me, do you, Latro?" "No," I said."I was afraid you wouldn't. I'm Pindaros, and your friend. This girl"—he nodded to the child—"is your slave, Io. And this is ... ah ...?" "Hilaeira," she said. By then my eyes had left her own, and I saw that she sought to conceal her breasts without appearing to do so. "It's not customary to exchange names during the bacchanalia. Now it's all right. You remember me, don't you?"I said, "I know I slept beside you and covered you when I woke."Pindaros explained, "He was struck down by the Great Mother. He forgets everything very quickly." "How terrible for you!" Hilaeira said, and yet I could see she was glad to learn I had forgotten what we must have done the night before.The priest had continued to instruct Io while we three spoke among ourselves. Now he said, "—gave to the child god the form of a kid."Io must have been listening to us; she turned aside to whisper, "He writes things down to remember. Master, yesterday you sat by yourself and wrote for a long time. Then this woman came to you, and you rolled up your book again." "Teleia, Queen of the Gods, was not deceived. With sweet herbs and clotted honey, she lured the kid away, coming at last to the isle of Naxos, where her bodyguard waited under the command of her daughter, the Lady of Thought."The last of the worshipers were rising now, many appearing so exhausted and ill that I wondered whether a beaten army could have looked worse. I felt I had seen such an army once; but when I tried to recall it, there was only a dead man lying beside the road and another man, with a curling beard, putting the horse-cloth on his mount.The black man, who must soon have grown bored with what he could understand of the priest's story, had gone to the lake to drink. Now he returned and gestured for me to rise.Indicating Pindaros, Hilaeira whispered, "He said the child was your slave. Are you this man's?" When I did not answer she added, "A slave can't own a slave; any slave he buys belongs to his master." "I don't know," I told her. "But I feel he's my friend."Pindaros said, "It would be discourteous for us to leave while your young slave is being taught. Afterward we can go looking for the first meal."I motioned for the black man to sit with me, and he did.Hilaeira asked, "You really don't remember anything, or know whether you're slave or free? How is that possible?"I tried to tell her. "There is a mist behind me. Here, at the back of my head. I stepped from it when I woke beside you and went to the lake to drink and wash. Still, I think I'm a free man." "But the Lady of Thought," continued the priest, "is not called so for nothing. She's a true sophist, and like her city follows her own interests alone, counting promises and honor as nothing. Though she had helped her mother, she saved the heart of the kid from the pot and carried it to the Descender."He continued so for some time, his voice (like the wind) toying with the fresh grass, while his followers gathered about us; but I will not give the whole of his story. We must go soon, and I do not think it important.At last he said, "So you see, we have a particular claim upon the Kid. His mother was a princess of our seven-gated city, and it was through the blue waters of our lake—right over there—that he entered the underworld to rescue her. Yesterday you helped celebrate that rescue." Then silence fell.Pindaros asked, "Are you finished?"The priest nodded, smiling. "There is a great deal more I could say. But little heads are like little cups, soon so full they can hold no more." "Then let's go." Pindaros stood up. "There should be some peasants around here who'll be happy enough to sell us a bite." "I will lead the worshipers back to the city," the priest told him. "If you wish to wait for us, I'll point out the farmhouses that feed us each year."Pindaros shook his head. "We're on our way to Lebadeia, and we must put a good many stades behind us today if we're to reach the sacred cavern tomorrow."Hilaeira's violet eyes flashed. "You're on a pilgrimage?" "Yes, we've been ordered to go by the oracle of the Poet God. Or rather," Pindaros added, "Latro has, and a committee of our citizens has chosen me to guide him." "May I go with you? I don't know what's happened—you certainly don't want to hear about my personal life—but I've been feeling very religious lately, much closer to the gods and everything than I ever did before. That's why I attended the bacchanal.""Certainly," Pindaros told her. "Why, it would be the worst sort ofbeginning if we were to deny a devotee our protection on the road." "Wonderful!" She sprang erect and brushed his lips with hers. "I'll get my things."I put on this chiton and these back and breast plates, and took up the crooked sword and the bronze belt I found with them. Io says the sword is Falcata, and that name is indeed written on the blade. There is a painted mask too; Io says the priest gave it to me yesterday, when I was a satyr. I have hung it about my neck by the cord.We have stopped at this house to eat cakes, salt olives, and cheese, and to drink wine. There is a seat here where I can spread this scroll across my knee in the proper way, and I am making use of it to write all these things down. But Pindaros said a moment ago that we must soon go.Now there are swarthy men with javelins and long knives coming over the hill.FIVEAmong the Slaves of the Rope Makers,IT IS THE CUSTOM to beat and abuse captives. Pindaros says this is because the Rope Makers despise their slaves but count us as equals, or at least as near to equals as anyone who is not a Rope Maker can be.Me they beat more than Pindaros or the black man until we found the old man sleeping. Now they do not beat me. They do not beat Hilaeira or her child much, either; but both weep, and they have done something to the child's legs so that she can scarcely walk. When my hands were freed, I carried her until we halted here.A moment ago a sentry took this scroll from me. I watched him, and when he left the camp to relieve himself I spoke to the serpent woman. She followed him and soon returned with my scroll in her mouth. Her teeth are long and hollow. She says she draws life through them, and she has drunk her fill.Now I must write of the earliest things I remember from this day, before they too are lost in the mist: the brightness of the sun and the billows of soft dust that lifted with each step to gray my feet and my legs too, as far as my knees. The black man walked before me. Once I turned to look back and saw Pindaros behind me, and my shadow, black as the black man's, stretched upon the road. I was beaten with a javelin shaft for that. The black man called out, I think telling them not to strike me, and they beat him also. Our hands were bound behind us. I feared they would strike my head because I could not protect it, but they did not.When the beating was over and we had walked a few steps more, I saw an old black man asleep near the road, and I asked Pindaros (for I knew his name) if they would bind him like the black man with us. Pindaros asked what man I meant. I pointed with my chin as the blackman does, but Pindaros could not see him, because he lay half-concealed in the purple shade of a vineyard.One of the slaves of the Rope Makers asked me what man it was I spoke of. I told him, but he said, "No, that is only the shadow of the vines." I said I would show him the sleeping man if he would allow me to leave the road. I spoke as I did because I thought that if the old black man awakened he would wish to aid the black man with us and might tell someone of our capture."Go ahead," the slave who had spoken to me said. "You show me, but if you run, you'll join our friends. And if there's nobody there, you'll pay for them again."I left the road and knelt beside the sleeping man. "Father," I whispered. "Father, wake up and help us." Because my hands were tied, I could not shake him, but I dropped to one knee and nudged him with the other as I spoke.He opened his eyes and sat up. He was bald, and the curling beard that hung to his belly was as white as frost."By all the twelve, he's right!" the slave who had come with me called to the rest."What is it, my boy?" the old man asked thickly. "What's the trouble here?" "I don't know," I told him. "I'm afraid they're going to kill us." "Oh, no." He was looking at the mask that hung about my neck. "Why, you're a friend of my pupil's. They can't do that." He rose, swaying, and I could see that he had fallen asleep beside the vineyard because he had drunk as much as he could hold. The black man gleams with sweat, but this fat old man shone more, so that it seemed there was a light behind him.To the slave who had come with me, he said, "I lost a flute and my cup. Find them for me, will you, my son? I've no desire to bend down at the moment."The flute was a plain one of polished wood, the cup of wood also; it lay upon its side in the grass not far from the flute.Several of the slaves of the Rope Makers crowded around staring. I believe the black man was the first such they had ever seen, and now they had seen two. One said, "If you want to keep your flute and cup, old man, you'd better tell us who you are." "Why, I do." The old man belched softly. "I do very much indeed. I am the King of Nysa."At that the little girl piped, "Are you the Kid? This morning a priest said the Kid was the King of Nysa." "No, no, no!" The old man shook his head and sipped twilighthued wine from his cup. "I'm sure he did not, child. You must learn"—he belched again—"to listen more carefully. Otherwise you will never acquire wisdom. I'm sure he said my pupil was the King from Nysa. King of Nysa, King from Nysa. You see, he was put into my hands when he was yet very young. I tutored him myself, and he has rewarded me"—he belched a third time—"as you behold."One of the slaves laughed. "By giving you all the wine you wanted. Good enough! I wish my own master would reward me like that." "Exactly!" the old man exclaimed. "Precisely so! You're a most penetrating young fellow, I must say."It was then I noticed that Pindaros stood with head bowed.The oldest slave said, "That's a nice flute you have, old man. Now hear my judgment, for I command here. You must play for us. If you do it well, you can keep it, for it offends the gods to take a good musician's instrument. If you don't play well, you'll lose it, and get a drubbing besides. And if you won't play at all, you've had your last carouse." Several of the others shouted their agreement."Gladly, my son. Most gladly. But I won't flute without someone to sing to my music. What about this poor boy with the broken head? Since he found me, may he sing to my fluting?"The leader of the slaves nodded. "With the same laws. He'd better sing well, or he'll screech a lively tune when we thwack him."The old man smiled at me, his teeth whiter even than his beard. "Your throat will be clogged with the dust of the road, my boy. You'll need a swallow of this to clear it." He held his cup to my lips, and I filled my mouth with the wine. There is no describing how it tasted—as earth, rain, and sun must taste to the vine, I think. Or perhaps as the vine to them.Then the old man began to flute.And I to sing. I cannot write the words here, because they were in no tongue I know. Yet I understood as I sang them, and they told of the morning of the world, when the slaves of the Rope Makers had beenfree men serving their own king and the Earth Mother.They told too of the King from Nysa and his majesty, and how he had given the King of Nysa to the Earth Mother to be her foster son, and to the Boundary Stone.The slaves of the Rope Makers danced as I sang, waving their weapons and skipping and hopping like lambs in the field, and the black man and Pindaros, and the woman and the child danced with them, because the knots that had bound them had been only such as little children tie, knots that loosen at a shaking.At last the song died at my lips. There was no more music.Pindaros sat with me for a time beside this fire, while the rest slept. He said, "Two of the lines of the prophecy were fulfilled today. Did you remember?"I could only shake my head."'Sing then! And make the hills resound! King, nymph, and priest shall gather round!' The god—he was a god, you realize that, don't you, Latro? The god was a king, the King of Nysa. Hilaeira was a nymph last night when we danced to the honor of the Twice-Born God. I'm a priest of the Shining God, because I'm a poet. The Shining God was telling you that you should sing when the King of Nysa called upon you. You did, and he took away the cords that bound us. So that part's all right."I asked him what part was not all right."I don't know," he admitted. "Perhaps everything's all right. But—" He stirred the coals, I suppose to give himself time to think, and I saw his hand shake. "It's just that I've never actually seen an immortal before. You have, I know. You were talking of seeing the River God, back in our shining city."I said, "I don't remember." "No, you wouldn't, I suppose. But you may have written about it in that book. You ought to read it.""I will, when I've written everything I still remember from today."He sighed. "You're right, that's much more important." "I'm writing about the King of Nysa, saying he was a black man like the black man with us."Pindaros nodded. "That was why he came, of course. As King of Nysa, he's that man's king, and no doubt that man's his faithful worshiper.The Great King's army, that's retreating toward the north, levied troops from many strange nations."Pindaros paused, staring at the flaming coals. "Or it may be that he was following the Kid. He's rumored to do it, and the mysteries we performed yesterday may have called the Kid to us. They're intended to, after all. They say that where the Kid has been, one finds his old tutor asleep; and if one can bind him before he wakes, he can be forced to reveal one's destiny." He shivered. "I'm glad we didn't do that. I don't think I want to know mine, though I once visited the oracle of Iamus to ask about it. I wouldn't want to hear it from the mouth of a god, someone with whom I couldn't argue."I was still considering what he had said first. "I thought I knew what that word king meant. Now I'm not sure. When you say 'the King of Nysa,' is it the same as when you say the army of the Great King is retreating?" "Poor Latro." Pindaros patted my shoulder as a man might quiet a horse, but there was so much kindness in it I did not mind. "What a pity it would be if you, who can learn nothing new, were to lose the little you know. I can explain, but you'll soon forget." "I'll write it out," I told him. "Just as I'm writing now about the King of Nysa. Tomorrow I'll read it and understand." "Very well, then." Pindaros cleared his throat. "In the first days, the nations of men were ruled by their gods. Here the Thunderer was our king in the same way the Great King rules his empire. Men and women saw him every day, and those who did could speak to him if they dared. In just the same way, no doubt, the King of Nysa ruled that nation, which lies to the south of Riverland. If Odysseus had traveled so far, he might still have found him there, sitting his throne among the black men."Often the gods took the goddesses in their arms, and thus they fathered new gods. So Homer and Hesiod teach us, and they were skilled poets, the true enlightened singing-birds of the Shining God. Often too the gods deigned to couple with our race; then their offspring were heroes greater than men—but not wholly gods. In this fashion Heracles was born of Alcmene, for example."I nodded to show I understood."In time, the gods saw that there were no thrones for their children,or for their children's children." Pindaros paused to look at the starry sky that mocked our little fire. "Do you remember the farmhouse where we ate, Latro?"I shook my head."There was a chair at the table where the farmer sat to eat. His daughter, that curly-headed imp who dashed about the house shouting, crawled into it while I watched. Her father didn't punish her for it, or even make her climb down; he mussed her hair instead and kissed her. So it was between the gods and their children, who became the kings of men. The kings of the Silent Country, to which we're being taken, still trace their proud lines from Alcmene's son. And if you were to travel east to the Empire instead, you'd find many a place where the Heraclids, the sons and daughters of Heracles, ruled not long ago; and a few where they rule yet, vassals of the Great King."I asked whether the farmer would not someday wish to sit in his chair again."Who can say?" Pindaros whispered. "The ages to come are wisest." After that he remained silent, stroking his chin and staring into the flames.SIXEosTHE LADY OF THE DAWN is in the sky. I know her name because a moment ago as I unrolled this scroll she touched it with her shellpink finger and traced the letters for me there. I have copied them just where she drew them—look and see.I remember writing last night, and what I wrote; but the things themselves have vanished. I hope I wrote the truth. It is important to know the truth, because so soon what I write will be all I know.Last night I slept only a little, though I rolled up this beautiful papyrus and tied it with its cords so I might sleep. One of the slaves of the Rope Makers woke me, sitting cross-legged beside me and shaking me by the shoulder."Do you know who I am?" he asked.I told him I did not."I am Cerdon. I let you leave the road when you saw ..." He waited expectantly."I'm tired," I told him. "I want to sleep." "I could beat you—you know that? You've probably never had a real beating in your life.""I don't know."The anger drained from his face, though it still looked dark in the firelight. "That's right, you don't, do you? The poet told me about you. Do you remember what you saw under the vines?"It was lost, but I recalled what I had written. "A black man, an old man and fat." "A god," Cerdon whispered. His eyes sought the heavens, and in the clear night found innumerable stars. "I'd never seen one before. I never even knew anybody who had. Ghosts, yes, many; but not a god."I asked, "Then how can you be sure?" "We danced. I too—I couldn't stand still. It was a god, and you saw him when none of the rest of us could. Then when you touched him, all of us could see him. Everyone knows what happened."Very softly the serpent woman hissed. She was beyond the firelight, but it gleamed in her eyes as in beads of jet. They said, "Give him to me!" and I heard the scales of her belly like daggers drawn from their sheaths as she moved impatiently over the spring grass. "No," I said."Yes, we do," Cerdon insisted. "Then I saw him as I see you now. Except that he didn't look like you. He didn't look like any ordinary man." "No," I said again, and let my eyes close."Do you know of the Great Mother?"I opened them again, and because I lay facedown with my head pillowed on my arms, I saw Cerdon's feet and the crushed grass on which he sat. The grass looked black in the firelight. "No," I said a third time. And then, "Perhaps somewhere I have heard of her." "The Rope Makers call us slaves, but there was a time when we were free. We pulled the oars in the galleys of Minos, but we did it for silver and because we shared in his glory."Cerdon's voice, which had been only a whisper before, fell lower, so low I could scarcely hear him, though my ears were so near his lips. "The Great Mother was our goddess then, as she is our goddess still. The Descender overcame her. That's what they say. He took her against her will, and such was his might that she bore him the Fingers, five boys and five girls. Yet she hates him, though he woos her with rain and rends her oaks to show his strength. The Rope Makers say the oaks are his, but that can't be. If they were his, would he destroy them?" "I don't know," I said. "Perhaps." "The trees are hers," Cerdon whispered. "Only hers. That's why the Rope Makers make us cut them down, make us dig out their stumps and plow the fields. The whole Silent Country was covered with oak and pine, when we were free. Now the Rope Makers say the Huntress rules Redface Island—because she's the Descender's daughter, and they want us to forget our Great Mother. We haven't forgotten. We'll never forget."I tried to nod, but my head was too heavy to move."We've been slaves, but we're warriors now. You saw my javelins and my sling."I could not remember, but I said I had."A year ago, they would have killed me if I touched them. Only they had arms, and the arms were guarded by armed Rope Makers, always. Then the Great King came. They needed us, and now we're warriors. Who can keep warriors slaves? They will strike him down!"I said, "And you wish me to strike with you," because it was plain that it was what he had come for."Yes!" His spittle flew in my face."There's no Rope Maker

Soldier of the Mist7Soldier of Arete317Glossary625

\ From the Publisher"SF's greatest novelist, and overall one of America's finest. . . a wonder, yes, a genius."-The Washington Post Book World\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyIn his foreword to Latro in the Mist, which pairs Gene Wolfe's acclaimed historical fantasies Soldier of the Mist (1986) and Soldier of Arete (1989), Wolfe reveals that the two novels are in fact his translations of the diary writings of Latro, a Roman mercenary wounded in battle in ancient Greece. Latro's head wound ruined his short-term memory, but bestowed upon him the gift of conversing with gods and goddesses. Copyright 2003 Reed Business Information.\ \