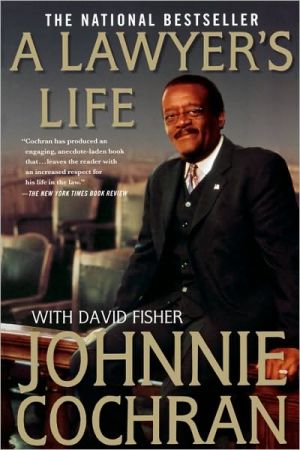

Lawyer's Life

The most famous lawyer in America talks about the law, his life, and how he has won.\ Johnnie Cochran has been a lawyer for almost forty years. In that time, he has taken on dozens of groundbreaking cases and emerged as a pivotal figure in race relations in America. Cochran gained international recognition as one of America's best - and most controversial lawyers - for leading 'the Dream Team' defense of accused killer O.J. Simpson in the Trial of the Century. Many people formed their...

Search in google:

Johnnie Cochran gained international recognition for leading the "Dream Team" defense of O.J. Simpson. But long before and since then Johnnie Cochran has been a leader in the fight for justice for all Americans. While often vilified for his defense of Simpson, Cochran emerged from the trial as a leading AfricanAmerican spokesperson. But he has done most of his talking through the courtroom in such high profile cases as: Abner Louima Amadou Diallo The Raciallyprofiled New Jersey Turnpike Four Sean "Puffy" Combs Patrick Dorismond Cynthia Wiggins Cochran explains how he has used the law to force fundamental changes in America, it was Cochran, critics still claim, who dealt the first "race card." Here is his answer to that and other accusations.The Los Angeles TimesCochran's book goes beyond just a highly readable recitation of his transformation from deputy district attorney to counsel in such history-making cases as those of Amadou Diallo, Abner Louima, Reginald Denny, Elmer "Geronimo" Pratt and, of course, O.J. Simpson. Cochran's case-by-case narrative spotlights a host of weak spots in the criminal justice system as well as (perhaps unintentionally) the complex and morally ambiguous role that lawyers play in identifying those flaws. — Edward Lazarus

A Lawyer's Life\ \ By Johnnie L. Cochran \ Dunne Books\ Copyright © 2002 Johnnie L.Cochran\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 0312278268\ \ \ \ Chapter One\ If it may please the reader . . .\ There is a young California Highway Patrol officer who begins work each night at almost exactly ten o'clock and finishes at 6:15 a.m. That's known as the graveyard shift; he chooses to work through the night because by that time the worst of Southern California's daily traffic jams have faded into the sunset and the job becomes the most interesting.\ During his eight and a half hours in the black-and-white patrol car he'll cover several hundred miles of Los Angeles freeway, mostly the 10 and the 110, upholding the law of the land. His patrol car is equipped to respond to a range of emergencies; there are ample medical supplies in the trunk and a shotgun in the back.\ There is no such thing as a typical shift on this job. A single serious accident might fill up most of his time, or he can drive smoothly through the night making as many as twenty different and very routine stops. But on this job the next minute is always one brimming with possibilities; the unexpected is what makes it intriguing. Usually, though, the first couple of hours are pretty routine. Traffic is light. The officer and his partner will assist drivers with disabled vehicles. They'll write some tickets, mostly for speeding. But in the early morning the bars around town close and the drunkdrivers hit the road. It's during those three or four hours in the middle of the night that damage will be done.\ This particular young man became a law enforcement officer in 1998. He was studying microbiology at UCLA, thinking about becoming a doctor, when his best friend joined the Highway Patrol. The job is exciting, his best friend reported, it's different. Try it. And so he did. He had been on the job only a few months the first time he saw a traffic fatality. A man driving home one night had a flat tire and parked on the side of the freeway to change it. It was nothing, a simple flat tire. But another driver wasn't paying attention, his car drifted onto the apron, just close enough to hit the man changing his tire. He had been killed instantly. The result of a ton of metal traveling at high speed hitting a human being was brutal, the young officer remembered, the victim's body was ripped up pretty badly. It was a serious welcome to the work.\ The uniform the officer wears is tan, with a blue stripe running down the seam of his trousers. His badge is a gold star. He has a campaign hat, the familiar Smokey the Bear model, but never wears it on the road. It's mostly for show, for dress occasions.\ It is still early in his career and he's been fortunate thus far. He's never had to draw his weapon; he's never been threatened. He's only been in three or four hot pursuits and each of them ended quickly and safely.\ He has been pleasantly surprised to discover that most of the people he has stopped for traffic infractions have treated him politely. Several speeders have told him they were racing home to go to the bathroom. Only occasionally have drivers reacted to the stop with anger. Three or four people have accused him of stopping them only because they are African-American, and to each of them he politely pointed out that it was night and the windows of their car were tinted, making it impossible for him to see who was inside. Several times the drivers of cars he had stopped warned him that they knew influential people, that they could cause problems in his career. Two people told him they were "personal friends of Johnnie Cochran."\ Obviously they failed to read this young officer's name tag. It reads "J. E. Cochran." Jonathan Eric Cochran. My son.\ Most people are quite surprised to learn that my only son is a police officer. Truthfully, when he called me from college and told me about this decision I was surprised, too. Surprised, but supportive. I've spent much of my life around law enforcement officers. Among my best friends is the former chief of police of Los Angeles, Bernard Parks. My brother-in-law and my friend for more than forty years, Bill Baker served in the L.A. Sheriff's Department for more than thirty years, rising to the rank of chief. At two different times in my life I served as a prosecutor in Los Angeles, for three years being the third-highest-ranking attorney in the L.A. County District Attorney's office. So there are few people in this nation with more respect for law enforcement officers-and the law-than me.\ That statement may surprise many people, too, particularly those people who most associate me with the criminal trial for murder and the acquittal on all charges of O. J. Simpson. The Simpson trial changed the lives of every person who participated in that trial. As advertised, it was indeed the "Trial of the Century." It had all the elements of great drama: a beloved black athlete was accused of murdering his estranged white wife; it had money and sex, race and gore; it had intrigue and mystery and showcased a cast of diverse and fascinating characters. The trial dominated the popular culture in almost all of its forms for more than a year. It was probably the subject of more conversations and arguments than any subject since the Vietnam War. And, most importantly, it was televised around the world.\ At the end of that trial not one of the participants walked out of that courthouse the same person he had been only months earlier. Our lives, too, had been changed forever.\ Prior to the Simpson trial I was among the best-known and respected attorneys in Southern California. During my legal career I had been involved in literally thousands of cases, ranging from prosecuting dangerous drivers to defending accused killers. I am the only attorney to have been honored in Los Angeles as both Civil Trial Lawyer of the Year and Criminal Trial Lawyer of the Year. I had represented victims and their families in some of the most notorious cases in Los Angeles history. I'd won several of the largest judgments in police negligence cases ever paid by the city. I'd prosecuted or represented people of all races and religions and from every social stratum. Among the many celebrities I'd represented-this was long before the O. J. Simpson case-were Michael Jackson and football Hall of Famer Jim Brown. I represented former child TV star Todd Bridges in an attempted murder case in which he was positively identified by the victim. And in the case that spanned several decades of my professional career, I represented Geronimo Pratt, a member of the Black Panther Party who had been wrongly convicted of murder. In the community of Los Angeles I served on the boards of several charities, I was active in civic organizations, and was a member of the Los Angeles Airport Commission-during the massive rebuilding of LAX-for almost thirteen years.\ I had an interesting and extremely successful legal practice, a strong marriage to a very bright and beautiful woman, I enjoyed a position of prestige and power within my community, and I had all the material possessions I needed to make me a very happy man. Life was good.\ So the Simpson trial was the sea change of my life. It changed my life drastically and forever in ways impossible to even imagine. It obscured everything I had done previously. Everything. As I later understood, being in the middle of the trial was somewhat like being in the eye of a great hurricane; living there in the center it was impossible to truly appreciate the magnitude of the winds swirling around me. Unlike other famous trials of the past, throughout the Simpson trial the television cameras allowed viewers to become emotionally invested in its outcome. At some point for many people it ceased being a trial in which the prosecutors and the defense followed long-established guidelines to determine an accused man's guilt or innocence, and instead became some sort of legal soap opera. My participation as the head of Simpson's successful defense team had made me one of the most easily recognized-and controversial-people in this country. I was loved and I was vilified. I received countless requests and offers-at times I got as many as five hundred phone calls a day-as well as hate letters and threats on my life and that of my family too numerous to count.\ Most of America, most of the world actually, came to know me and define me only by my work in that trial. I was the man who had told the jury, "If the glove doesn't fit, you must acquit." I was the attorney who pulled a knitted cap over my head and questioned its value as a disguise. But much more than anything else, I was the attorney accused of "playing the race card." I was accused of using the fact that O. J. Simpson was a black man to convince black jurors to vote to acquit him-not because he might be innocent of the crime, but rather because it was time in America for African-Americans to take retribution for the legal crimes that had been committed against them for almost three centuries.\ The attacks on me personally were voluminous and ferocious. In a column in The New York Times, best-selling author Gay Talese described me as "a peerless exponent of racism as a weapon of defense." In a best-selling book, author Dominick Dunne wrote, "[Johnnie Cochran's] gotten rich over the years suing the LAPD for infractions against black people . . ." Infractions, I suppose, like breaking into an innocent young black man's apartment and killing him, or infractions like stopping an innocent young black man for speeding while he was driving his pregnant wife to the hospital and killing him.\ And then, when I was retained in New York City by Abner Louima, a man who had been beaten and sodomized with a plunger by a policeman in a police station while other policemen stood guard, an hysterical columnist in the conservative New York Post wrote about me, "The man who cynically turned West Coast justice on its ear in service of the guilty is now poised to do a similar number on the city of New York."\ This columnist added, "(H)istory reveals that he will say or do just about anything to win, typically at the expense of the truth." This columnist's ignorance about my career, my "history," did not surprise me. Obviously she had not taken the time necessary to understand what had happened in that Los Angeles courtroom. I sued the newspaper for libel, but the case was dismissed as the column was judged to be "protected opinion."\ But I also received considerable acclaim for my work in the Simpson case. People of all races approached me on the street to congratulate me. In restaurants people would send over champagne. One perk I most definitely enjoyed was that my wife, Dale, and I didn't have to stand in long lines at local movie theaters, the manager simply invited us inside. African-Americans in particular were extremely supportive. Extremely. They were very proud that a black man proved that he was among the leading attorneys in the nation, that a black professional could compete successfully on the highest level.\ More significantly than that, until the Simpson verdict, many people in the majority community believed that the legal system in this country functioned properly. Guilty people were convicted and innocent people went free. Well, for members of that majority it did, but for the many African-Americans and other minorities, the justice system often had failed to provide justice. Sometimes it seemed to me that I'd spent too many hours of my life defending the rights-and the reputations-of people who had been shot, beaten, or choked by police officers. The reality that the system failed to protect minorities was sort of our national secret, the dirt swept under the rug. The absolutely ecstatic reaction to the Simpson verdict by so many people from the minority communities surprised and probably shocked a great number of people in the majority; and the fact that it did was simply an indication of how great is the division between the races in America.\ I'm not sure that even I truly appreciated the extraordinary impact of the Simpson verdict until my wife and I visited South Africa. By that time I was used to being recognized in America. But one day in South Africa we visited the black township of Soweto. Until recently in South Africa, blacks had been forced to live in ghettos. So a township had become a small city in which lived people of every income level-but all of them black. We drove into Soweto in two vans and stopped at a small restaurant. As I got out of the car I saw a child look at me, then start running toward me. Almost immediately he was followed by other children and adults. It seemed like we were surrounded by the whole neighborhood. And they started saying my name, and they sang a song about me, a song that had been written about me. I was astonished. As we ate lunch there that day people came up to me with pictures for me to sign. It was stunning. These were people who didn't even have television sets, yet somehow they knew who I was. What had happened in that courtroom in Los Angeles had resonated with people of color literally throughout the world.\ Before becoming involved in the Simpson case I'd seriously considered retiring-though admittedly Dale never for even a moment took me seriously-but at least the thought was in my mind. But my success in the Simpson case provided me with the kind of high-profile celebrity and visibility few attorneys have ever enjoyed. Court TV hired me to cohost a nightly TV show. Characters in movies made reference to me; in one of the Lethal Weapon movies, for example, Chris Rock warned a suspect after reading him his Miranda rights, ". . . and if you get Johnnie Cochran I'll kill you." In Jackie Brown Samuel L. Jackson told a compatriot that the lawyer he was hiring was so good, "He's my own personal Johnnie Cochran. As a matter of fact, he kicks Johnnie Cochran's ass." I appeared as myself in the Robert De Niro/Eddie Murphy film Showtime. I appeared often as a guest on shows ranging from the very serious Nightline to Larry King's show to sitcoms like The Hughleys. Saturday Night Live and Seinfeld parodied me. I was at the center of the uniquely American celebrity blitz.\ It was fun. At times it was a lot of fun. And I knew that accepting it good-naturedly, even participating in it, helped soothe some of the angry feelings from the Simpson case.\ But I never forgot who I was, what I believed to be my purpose in life, and those things that I had fought for my entire professional career. As a result of my efforts in the Simpson case I was given the extraordinary opportunity to express those views publicly, loudly, and often. And the attention that I received caused me to get involved in some of the most interesting and significant cases of my career. Cases that involved exactly the same institutionalized injustice I had been fighting for decades. In New York City, for example, in addition to Abner Louima's family, I represented the family of a man named Patrick Dorismond, a black man who said no to a drug deal offered by undercover police and was shot and killed. I represented, for a time at least, the family of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed African immigrant who was shot nineteen times-nineteen times-by police officers. Working with my friends and co-counsel from the Simpson case, Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck, we were able to cause significant changes to be made in the basic policies of the NYPD.\ In Buffalo an upscale mall permitted buses full of tourists from across the border to pull directly in front of the shops, but buses from the surrounding minority neighborhoods were not permitted to enter the mall. They had to stop on the far side of a major thoroughfare. The mall management made some ridiculous explanations for this policy, but its real purpose was obvious. As a result a teenage mother named Cynthia Wiggins, who had just been trying to get to her minimum-wage job at the mall, was run down and killed by a truck. An excellent Buffalo attorney named Bob Perk asked me to join him in this civil case, in which we set out to send a strong message to all businesses that still find indirect means to discriminate against minorities.\ In New Jersey, Peter, Barry, and I represented several young black and brown men driving on the New Jersey Turnpike to college who were stopped by state troopers for absolutely no reason-except that they fit an illegal law enforcement profile. When their van apparently started rolling backward the state troopers started shooting. This enabled us to focus national attention on the heinous practice of racial profiling, one of the core problems affecting race relations in this country.\ And we represent Dantae Johnson, a black teenager who was afraid of New York City cops, so when two officers stopped to question him he ran away. Dantae Johnson was suspected of no crime, there was no emergency, yet the sight of a young black man running away was enough for a police officer to believe he must have done something wrong. The officer chased him in his squad car, pulled his gun, and while attempting to apprehend Johnson shot him. After six months in the hospital Johnson partially recovered. Peter, Barry, and I set out not just to guarantee his financial future-that is the easiest part-but also to make sure this kind of irresponsible shooting never happened again. Additionally, we took a personal interest in Dantae Johnson, and set out to help him put together a new life.\ Although I had vowed that the Simpson case would be my last criminal trial, and most certainly my last celebrity criminal trial, I defended Sean "Puffy" Combs, the rap star/entrepreneur accused of firing a gun in a nightclub and possession of a weapon found in the SUV in which he fled the scene. I can't recall another case in which charges similar to these had resulted in a two-month trial. In most jurisdictions this case would have been settled with a fine; in California this would have been a misdemeanor. But Puffy Combs was an extremely successful young black man. To me, this was an example of the system trying to knock down a very successful black man, as well as an opportunity for an ambitious prosecutor to make a reputation for himself. I couldn't turn the case down.\ The Simpson case gave me the platform to try to change some of those things that need to be changed in this country. Many of the cases I accepted were vehicles to force those changes to be made. They were not all racial discrimination cases, some of the most important civil cases concerned basic property rights, for example. But whatever the dispute, it was the Simpson case that put me squarely in a position to make a difference. And that was precisely the reason I had become an attorney.\ I am a black man. I am the great-grandson of slaves, the grandson of a sharecropper, the son of a hardworking businessman. I am at least a fourth-generation American: This is my heritage and my country and I am so very proud of it. I believe in the goodness of this nation even when I have been so often exposed to the worst part of it. I believe completely in the legal system as it was designed to function by the Founding Fathers, although I know from my experience that too often it doesn't work that way. Many of my battles in American courtrooms have been a simple attempt to extend the benefits of that system to those people who for so long have been excluded. My career did not begin-nor did it end-with the trial of O. J. Simpson. I didn't create myself to try that case and no one can truly know who I am merely by virtue of my work in his defense.\ I am also an attorney. A lawyer. Just about as long as I can remember the only thing I wanted to do with my life was practice law. My mother wanted me to be a doctor, but I wanted to be a lawyer. That was probably the first case I won; my parents supported me in pursuit of my dream. I can't remember the precise reason that I decided on the law, but I know that it had much to do with the fact that I liked to argue. Liked to argue? I loved it, I absolutely loved it. In high school I excelled in debate. I don't remember a single question we debated, but the questions didn't matter as I was able to take either side of almost any reasonable statement. But I do remember that incredible surge of power and satisfaction I felt when I made a strong argument and dragged people over to my side of the question.\ I learned to defend my ideas and beliefs at the Cochran family dinner table. My father, Johnnie L. Cochran Sr., set the intellectual standard for his children. He had been the valedictorian of his class at Central Colored High when he was only fourteen years old. He expected us to work as hard as was necessary to reach our fullest potential. And he seemed to think our fullest potential was always a little fuller than we did.\ My mother, Hattie B. Cochran, was the disciplinarian. If we did something wrong, if we got out of line, it was mostly my mother who would apply the punishment. One time I talked back to my mother and the next thing I knew my parents had packed a small bag for me and were taking me to reform school. Reform school! I hadn't even said anything bad, I just answered back to her. If I close my eyes I can see my two sisters, Pearl and Jean, sadly waving good-bye to me as I left for that reform school. Fortunately, my parents gave me a second chance. I learned in that house in the projects of Alameda, California, the value of the English language and the importance of using it correctly to make myself heard. I had to just survive.\ I do remember with great clarity the day of May 17, 1954, one of the most important days of my life. I was sixteen years old, in the eleventh grade at L.A. High School. On that day the Supreme Court of the United States issued its decision in the case of Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The court ruled that the long-accepted practice of "separate but equal" that had legally permitted segregated facilities to exist in this country was unconstitutional. "Separate but equal" was inherently unequal. This decision marked the beginning of the end of legalized racial discrimination. And the man who had made that happen was a black lawyer named Thurgood Marshall, the only man besides my father that I idolized, who later became the first black justice on the Supreme Court. I didn't know too much about what a lawyer did, or how he worked, but I knew that if one man could cause this great stir, then the law must be a wondrous thing. I read everything I could find about Thurgood Marshall and confirmed that a single dedicated man could use the law to change society. When I was growing up, first in Shreveport, Louisiana, and later Los Angeles, the law was not a profession easily accessible to "Negroes." Black people were considered qualified mostly for blue-collar work. Service jobs. Labor. A few black men, like my father who was an insurance salesman, worked for black-owned companies serving the black community. Black men rarely were able to enter elite professions like medicine or the law. In fact, the only black lawyer most people knew about was Algonquin J. Calhoun, a bumbling caricature from the Amos 'N Andy Show.\ So I became a lawyer to change society for the better. I wanted to be like my idol Thurgood Marshall. In retrospect that seems pretty audacious, but I truly believed that if I worked hard enough, if I was smart enough, if I wasn't afraid to stand up and say loudly to the whole world what I knew to be true, I could do that. Me, Johnnie Cochran, the great-grandson of slaves, I could cause society to change.\ It has taken society just a little bit longer than I originally anticipated to make some of those changes. And truthfully the world still has many more changes to make before I'll be satisfied. With tremendous optimism and perhaps slightly less realism, I began my personal efforts to change the world after graduating from the Loyola Marymount University School of Law in 1962, becoming a member of the California bar in January 1963.\ There was not a lot of opportunity in the legal profession for aggressive young black lawyers in 1963. This was even before corporate, criminal, or general practice law firms began hiring a "token black." Most law firms were what was called "lily white." In fact, four decades later-four decades-there are still astonishingly few black partners at America's major law firms. During law school I became the first black law clerk to work in the Los Angeles City Attorney's Office. I was assigned to represent the great city of Los Angeles in disputes involving less than $200. There is no lower place to start a career in the legal profession than small claims court. I defended the city in cases involving everything from potholes to puddles. After passing the bar I was offered a staff job. So I began my career as a deputy city attorney, one of only three African-American attorneys in the Los Angeles City Attorney's Office. As there was no shortage of young black men being prosecuted, it seemed to make good sense to have young black men prosecute them.\ I made $608 monthly. My first day on the job I prosecuted thirty traffic tickets. I won fifteen or sixteen cases in a row. I was pretty pleased with myself. I must be pretty good, I thought. While I wasn't exactly changing the world, at least I was making the streets of Los Angeles a little safer. And then I lost my first case. I probably lost two cases that day. As I learned very quickly, any attorney who claims to have never lost a case simply hasn't tried enough cases. Any attorney who has spent considerable time in a courtroom has lost cases. And they should lose some cases, because not every suspect accused of a crime is guilty and not every paying client is innocent. The facts aren't always as they initially appear to be.\ There probably were less than a thousand black lawyers in the entire country. While there were no laws against black men becoming lawyers, there certainly were some very high barriers placed in their way. I had been raised to believe that the secret to success was simply preparation, preparation, and preparation. But I saw that no matter how prepared black attorneys seemed to be, they never got the opportunity to prove their ability. They never got the high-profile cases. When they did succeed the media rarely reported it, which might have led to more work.\ I never tried to compete against white attorneys; rather, I competed against the standards. All I ever asked for was the opportunity to prove that black professionals were the equal of men-there weren't very many women in the professions, either-of any ethnic background. I wasn't interested in being a crusader, I had no intention of waving a big sign around, I just intended to do my job successfully every day. If I did that, I knew, it would be difficult to ignore me.\ For several months I successfully prosecuted cases in traffic court. And I was good at it. If you received a traffic ticket, you did not want to be prosecuted by young Johnnie Cochran. Many defendants pleaded guilty in exchange for reduced fines, but when an individual fought the ticket we had to have a jury trial. I'm sure it would be difficult for those millions of people watching the Simpson trial to visualize me in front of a jury fighting as vigorously, but certainly without the resources and experience, to convict a driver of speeding. It probably was that long ago in my career that I first fell in love with juries. I have stood in front of several hundred juries; no two juries have ever been alike. I have always loved the concept that six or twelve men and women who don't know each other and often have very little in common can come together for a brief period of time, listen to the evidence presented, and work together to reach a conclusion. I've lost cases in front of juries, and I may have disagreed with the verdict, but rarely have I been disappointed by the efforts of a jury to reach a verdict based on the evidence presented to them.\ In my traffic court if you got caught speeding, it's money you'd be needing. Obviously as a young lawyer, I also had a lot of work to do on my courtroom rhymes.\ Eventually I began prosecuting a wider range of cases. Too often, though, the defendants would arrive in court bruised and beaten, with broken arms and noses. Most of the time the police officers were white and the defendants would be young black men. And it would be my assignment to prosecute these young men for resisting arrest or interfering with an officer performing his duty. "Flunking the attitude test," as the police officers referred to it. Often the defendants would be crying. Their lawyers would be crying. And almost inevitably the defendants' mothers would be sitting in the rear of the courtroom crying.\ Day after day police officers would get on the stand and respond to my questions by testifying that reasonable force was used while making the arrest; that the defendants' faces came into contact with the sidewalk when they resisted.\ On any given day it would look to an observer that the law was being upheld, that the system was functioning. The problem was that any given day could have been almost any day. The same testimony was repeated over and over as if the police officer were reading from a script. The defendants always, always had resisted. The police officers never, never had used anything but reasonable force. And my job was to stand up there and make it all look as if it was true. A system was working, just not the legal system. This was theater. This was a gentlemen's arrangement that had evolved over time. Everybody knew their lines, the police officer, the judge-and me. It took me a while to understand the reason for this charade; by proving the defendant had resisted arrest or interfered with a police officer the city would not be liable for any injuries that the defendant had suffered. The theory was that since it was his fault he had been injured, he couldn't sue the city for the actions of the LAPD.\ I started to feel like a pawn. What could appear to be more fair than having a black man prosecuting black criminals? There are moments when I look back on my career and I wonder, I wonder, how could I have done some of the things that I did? But I had been raised to believe in the American system of justice and it took some time for me to accept the fact that the system had more to do with promoting social issues and the public convenience than justice. In fact, it didn't even matter much if the defendant was white. The general belief was that if the police officer arrested him, he must have been doing something wrong, even if the evidence presented did not support the specific charge. It was accepted by the white majority that police officers did not lie; and it was pretty much accepted by the black minority that there wasn't too much that could be done about it when they did.\ It appeared as though I was doing an excellent job, I won almost all of my cases, but these cases were difficult to lose. We were all playing roles in a carefully crafted play. We knew it, but we didn't admit it. The only one who didn't know his lines was the defendant. If he couldn't afford counsel and was assigned an overworked public defender he had almost no chance at all. The public defenders had their role in this play, too. If the defendant could afford a private lawyer he at least had a reasonable chance of getting a hung jury and walking out of the courtroom.\ Finally I just couldn't take it anymore. I couldn't continue to go along to get along. At that time I could not intellectually explain what I was feeling; it took me a long time to understand it. William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American black writer, editor, educator, and impassioned public speaker who spent his life crusading for black rights, finally renouncing his citizenship and living in Ghana. The Harvard-educated Du Bois, who had called upon black soldiers returning from World War I to "marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight the forces of hell in our own land," wrote a book in 1903 entitled The Souls of Black Folks. In this book he explained that African-Americans have a dual consciousness. We are both black and American, or "Negro" and American, as he wrote. But black Americans had two souls, two ways of thinking, two unreconciled strivings in one dark body. And often these two souls are at war with each other, with only dogged strength keeping black people from being torn asunder.\ What he was describing was a racial split personality. That is exactly the way I started to feel. And as W.E.B. Du Bois had written half a century earlier, it was tearing me apart. I was prosecuting bad guys, but most of the bad guys were black. And maybe, just maybe, some of them weren't really so bad. Maybe what they were saying, day after day, was true. Maybe they were telling the truth and the Los Angeles police officers were lying. Maybe these defendants were coming into contact with the cement sidewalk not while resisting arrest, but rather when police officers slammed them into the ground.\ It became obvious to me that these police officers were lying, that the judges knew they were lying and willingly accepted it, and that I had become an active participant in this charade. I decided to stop. I told my boss I refused to prosecute any more police abuse cases. This wasn't quite a declaration of personal independence, it was just one young lawyer calmly telling a senior deputy city attorney that he didn't want to prosecute these cases anymore.\ Fine, he said. That was perfectly acceptable and I was assigned other cases. But inside me a passion had been born. I don't think I verbalized it at that time, I can't remember discussing it with anyone, but I knew that these suspects were not being properly represented, that they were being beaten and abused by public servants charged with protecting them, and I knew that I wanted to move to the other side of the courtroom to try to stop this injustice.\ I left the City Attorney's Office in 1965 and joined the private practice of a black criminal lawyer named Gerald Lenoir. We became Lenoir & Cochran. He was a fine lawyer, a very intense man, and he had built a successful practice. There was no shortage of black men who needed a criminal lawyer. And every one of his clients was black. When I started he told me, "Johnnie, we are going to make money backwards!" I wasn't quite sure what he meant, but I did like the sound of it. I had always been able to earn enough money to survive, but I aspired to more than that. I did want to make a difference in this world, but admittedly I also wanted to make money doing it.\ Gerald Lenoir helped complete my education in the practice of law. He emphasized the fact that we were doing the business of law. I had great confidence in my ability, but I had little practical experience. He taught me how to run a private law practice. While working for the city I had won most of my cases; but in private practice I learned how difficult it really was to beat the city.\ Gerald Lenoir had two beautiful daughters and two fine sons whom he loved with all his heart. His daughters were students at the University of Wisconsin and each fall he would drive them halfway across the country to Madison, Wisconsin. On August 11, 1965, while Gerald was on his way to Wisconsin, two young black brothers, Marquette and Ronald Frye, were stopped by police for reckless driving in the Watts section of Los Angeles. Watts was the heart of the black ghetto. This stop was the type of thing that happened there every day, and a crowd gathered around the police car to watch. The boys' mother arrived and an argument began. Eventually all three Fryes were arrested and the police apparently used excessive force-they began hitting the brothers with their wooden batons-to get them into a squad car.\ The crowd began to close in and the police called for reinforcements. When more cops arrived the crowd broke up into small groups. The anger and frustration that had been building in the inner cities of America for decades finally exploded into violence. The Watts riots lasted six days. When it ended thirty-four people had been killed and 856 people had been injured. The fires that burned through Watts destroyed 209 buildings and hundreds more were damaged. Property loss was estimated to be more than $100 million. Four thousand people were arrested for loitering, looting, and basically just being black. Four thousand people. And every one of them needed an attorney. Our phones started ringing and long lines began forming outside our office. We had more clients than I had ever imagined possible. People were coming early in the morning till after midnight. This was the most intensive on-the-job training course anyone ever got. But having been part of the system, I knew how it worked and I was able to do a good job for many of my clients. The Watts riots marked the beginning of the racial explosion that would shake America over the next few years. But for me professionally, business could not possibly have been better. At night I would come home with my pockets filled with cash. We were making as much as $8,000 a day. Obviously that wasn't all my money, but enough of it was-and only a few weeks earlier I'd been earning considerably less than a thousand dollars a week.\ By the end of that year I felt ready to open my own practice. I was nervous about it, but I was ambitious; I had confidence in my ability and I had very large aspirations. I decided to lease an office in the Union Bank Building at the intersection of Wilshire Boulevard and Western Avenue. It was a prestigious building in the perfect location for me. I wanted to be on Wilshire Boulevard because it was a major east-west street and ran right through the heart of the white business district. Western Avenue ran north-south and I wanted to be on that street because the poor people I would be representing could take the bus up that street right from the black neighborhoods to the stop outside my office. The building wasn't exclusive or restricted, code words meaning blacks were not allowed, but there was not a single black tenant in that building. In fact, there was only one black lawyer on Wilshire Boulevard. The Los Angeles Club, a well-known men's club, was on the top floor of the Union Bank Building. I knew I couldn't be a member of that club, but I didn't care about that, I just wanted to be in that building. There were several vacant offices, but the management was reluctant to rent space to me.\ I was not a racial activist at that time. I hadn't been brought up to be bitter or angry about the racism that had closed most avenues of opportunity to African-Americans. Throughout my childhood, racial discrimination had not been part of my experience. I don't remember ever feeling that my race was holding me back; a reason for that, I long ago understood, was that my father did not want any of his children using racism as an excuse for failure. So as a child I learned to integrate easily. Only thirty of almost two thousand students at Los Angeles High School were black, for example. But that was never an issue with me. I had several close white friends and would often spend time at their houses. And at their homes I was exposed to those things that success could buy. It was only after I became part of the system that I began to understand what it so often meant to be a black man in America.\ Don't misunderstand me; I love this country. I am so very proud to be an American. I believe with all my heart in the words of the Constitution. But for African-Americans it is impossible to ignore the reality of racism. It was while working in the City Attorney's Office that I fully realized how the system actually worked to curtail the rights of black Americans.\ I was very naive. The fact that the building management did not want me as a tenant because I was an African-American was not the first thought that came into my mind. A few years earlier they might have been able to get away with it. But the civil rights movement was making substantial progress and the management needed a legitimate reason to keep me out of the building. "You've never been in business," they explained. "You have no experience." Finally, though, they agreed to rent office space to me-on the condition that my father co-sign my lease.\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from A Lawyer's Life by Johnnie L. Cochran Copyright © 2002 by Johnnie L.Cochran\ Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ \

\ From Barnes & NobleIs any lawyer in America more famous or more controversial than Johnnie Cochran? Whether he is masterminding the defense of O. J. Simpson, representing Michael Jackson, or lecturing Larry King on racial profiling, Cochran is news. In this candid autobiography, the dapper attorney puts himself on the stand, explaining his thoughts and courtroom strategies in numerous high-profile cases and discussing his effect on American law. Cochran writes frankly about his much-criticized use of the "race card" in the Simpson case and discusses how media attention can force fundamental change in American justice.\ \ \ \ \ The Los Angeles TimesCochran's book goes beyond just a highly readable recitation of his transformation from deputy district attorney to counsel in such history-making cases as those of Amadou Diallo, Abner Louima, Reginald Denny, Elmer "Geronimo" Pratt and, of course, O.J. Simpson. Cochran's case-by-case narrative spotlights a host of weak spots in the criminal justice system as well as (perhaps unintentionally) the complex and morally ambiguous role that lawyers play in identifying those flaws. — Edward Lazarus\ \ \ Publishers WeeklyAs Cochran freely concedes, his representation of O.J. Simpson transformed him from a lawyer into a celebrity. In this memoir of his professional life, he tries to put that case in perspective. Although a fierce critic of the racism he sees in the legal system and among the L.A. police, Cochran says the common perception that he is anti-law enforcement is wrong; he began his career as a prosecutor, but he is on a mission to eradicate racism wherever he finds it. Long before the Simpson case, he made a name for himself (and a small fortune) by successfully bringing police brutality cases on behalf of African-Americans like Barbara Deadwyler, whose husband was shot dead for no apparent reason while rushing his pregnant wife to the hospital. Cochran lost that early case and many others because, in his view, white juries refused to believe that police officers would lie under oath. Unfortunately, this memoir reads as though it was dictated to co-author Fisher (My Best Friends, with George Burns): it drifts from one legal war story to the next, often repeats details and occasionally leaves thoughts dangling. And that's a shame, because Cochran's experience gives him the authority to utter some uncomfortable truths, among them that justice is often reserved for the wealthy. Worse yet, he says, racism permeates the entire system, from the cop on the beat to the judge on the bench. Cochran musters case after case in support of these conclusions. This revelatory, often dismaying account provides a cogent explanation of why many African-Americans have such a jaded view of our legal system. (Oct.) Copyright 2002 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalBest known for his role in the "Trial of the Century" as O.J. Simpson's lead attorney, Cochran (Journey to Justice) describes how this high-profile case changed his life, how it became a "legal soap opera," and how he found himself both loved and hated, enduring threats against him and his family. He also discusses his efforts for other clients, including Amadou Diallo, Abner Louima, and Michael Jackson.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsThe most well-known African-American attorney (and perhaps most well-known attorney, period) of our time spins tales of courtroom drama, racism, and the good life. \ Many readers, it seems fair to say, will want the answer to just one question: "Did O.J. do it?" Cochran, the captain of O.J. Simpson’s Dream Team, provides a suitably elusive answer in several parts, which boils down to this: Simpson always insisted, in privileged conversations with his attorney, that he didn’t; the jury found Simpson innocent of the charge of murdering his wife because the state did not prove its case beyond any reasonable doubt; a neo-Nazi cop (who, Cochran alleges, though apparently a "reasonably articulate professional, in fact . . . was a lying thug") was after Simpson for his own reasons. Granted, Cochran writes of the post-verdict Simpson, "it is fair to say that some of the things he’s said and some of the schemes in which he’s gotten involved were probably not as well thought out as they should have been"—well, that’s no reason to torment the guy or suspect him of doing evil. On O.J., though, Cochran offers less meaningful detail than he does on the celebrated cases of Amadou Diallo and Abner Louima, along with many other less widely reported trials, even though it was l’affaire Simpson that made him a household name—and apparently added greatly to his wealth, even if Cochran has trouble deciding from one page to the next whether he’s rich or merely comfortable. This hurried memoir may frustrate readers seeking insight into Cochran’s inarguably brilliant legal mind, as there is little here on his education, influences, and formative experiences. Still, Cochran does give some accounting of hisworking methods, which emphasize "preparation, preparation, and then additional preparation." As well, he ably explores the depth of racism in American society and the consequent difficulty of African Americans and members of other minority groups to find justice. In doing so, Cochran rises to impassioned eloquence—and Americans who do not know firsthand the truth of his arguments may well feel ashamed after reading this.\ A split decision, then, though lawyers-in-training and close students of current events should find value in Cochran’s pages.\ \ \