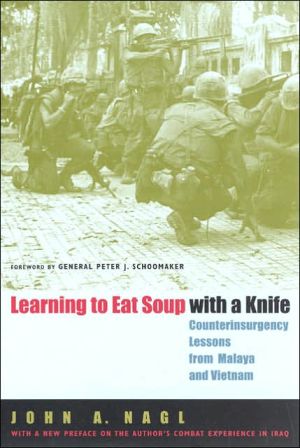

Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam

Invariably, armies are accused of preparing to fight the previous war. In Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife, Lieutenant Colonel John A. Nagl—a veteran of both Operation Desert Storm and the current conflict in Iraq—considers the now-crucial question of how armies adapt to changing circumstances during the course of conflicts for which they are initially unprepared. Through the use of archival sources and interviews with participants in both engagements, Nagl compares the development of...

Search in google:

Invariably, armies are accused of preparing to fight the previous war. In Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife, Lieutenant Colonel John A. Nagl—a veteran of both Operation Desert Storm and the current conflict in Iraq—considers the now-crucial question of how armies adapt to changing circumstances during the course of conflicts for which they are initially unprepared. Through the use of archival sources and interviews with participants in both engagements, Nagl compares the development of counterinsurgency doctrine and practice in the Malayan Emergency from 1948 to 1960 with what developed in the Vietnam War from 1950 to 1975. In examining these two events, Nagl—the subject of a recent New York Times Magazine cover story by Peter Maass—argues that organizational culture is key to the ability to learn from unanticipated conditions, a variable which explains why the British army successfully conducted counterinsurgency in Malaya but why the American army failed to do so in Vietnam, treating the war instead as a conventional conflict. Nagl concludes that the British army, because of its role as a colonial police force and the organizational characteristics created by its history and national culture, was better able to quickly learn and apply the lessons of counterinsurgency during the course of the Malayan Emergency. With a new preface reflecting on the author's combat experience in Iraq, Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife is a timely examination of the lessons of previous counterinsurgency campaigns that will be hailed by both military leaders and interested civilians.

Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife\ Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam \ \ By John A. Nagl \ University of Chicago Press\ Copyright © 2005 John A. Nagl\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 0-226-56770-2 \ \ \ Preface\ Spilling Soup on Myself \ Authors generally learn something about their subject matter, and then write about it. I took the opposite approach. Eight years after beginning my research into counterinsurgency and a year almost to the day after the publication of the first edition of this book, I deployed to Iraq to practice counterinsurgency as the Operations Officer of the First Battalion of the 34th Armored Regiment, the "Centurions." From September 24, 2003, through September 10, 2004, I was privileged to serve as Centurion 3 in Khalidiyah, a town of some 30,000 between Fallujah and Ramadi in the Sunni Triangle.\ The experience was searing. The Task Force was built around a tank battalion that had been designed, organized, trained, and equipped for conventional combat operations. The enemy we confronted was implacable, ruthless, and all too often invisible. Our yearlong confrontation in Al Anbar Province was bloody and difficult for the insurgents, for our soldiers, and for the population of the region. It was without a doubt the most intense learning period of my life.\ The experience of fighting insurgents in Iraq made me think again about the views expressed in thisbook-assessments of the British army in Malaya and, especially, of the American army in Vietnam. Rereading my work now, I am surprised by how much I was able to understand of counterinsurgency before practicing it myself and simultaneously appalled at some of my presumptions and errors. In the few pages of this preface I hope to point out omissions and missteps from that first edition, written before my own physical immersion in counterinsurgency, while highlighting some of the things I feel I got right the first time. It is my sincere hope that the book may be of use to those attempting to make our armed forces more effective in what promises to be a long struggle against enemies who fight freedom with the ancient art of insurgency.\ Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife\ T. E. Lawrence's aphorism that "Making war upon insurgents is messy and slow, like eating soup with a knife" is difficult to fully appreciate until you have done it. Intellectually grasping the concept that fighting insurgents is messy and slow is a different thing from knowing how to defeat them; knowing how to win, in turn, is a different thing from implementing the measures required to do it.\ This is perhaps the most basic flaw in the book that follows. There is something of a blithe sense that defeating the Communist insurgents in Malaya was easy once Sir Gerald Templer and Harold Briggs showed the British army what to do, and that the American army could similarly have won in Vietnam if only it had adopted earlier the changes promulgated by Creighton Abrams and Bob Komer. The truth is rather more complex. Changing an army is an extraordinarily challenging undertaking. Britain was able to adapt to defeat the insurgency in Malaya for many reasons, but those reasons certainly included the British army's comparatively small size and its organizational culture that had been honed in a number of small wars fought over generations. Changing the American army is a task of an entirely different scale, a challenge that the organization struggled with during the Vietnam War.\ The army's adaptations in Vietnam were ultimately too little too late to defeat the insurgency there. By contrast, the army has adapted much more rapidly to the challenge of insurgency in Iraq. My own personal experience is illustrative of the larger challenge and response. Task Force 1-34 Armor was preparing for high-intensity combined arms warfare in July of 2003 when it was notified that it would deploy to Iraq; by September, two of its three tank companies were conducting combat operations in the Sunni Triangle mounted on Humvees and dismounting to fight as dragoons, with just one company fighting from M1A1s. In the intervening sixty days, the battalion had been issued new weapons systems and vehicles ranging from machine guns to up-armored Humvees. It reorganized its combat vehicle crews and maintenance teams, designed and implemented counterinsurgency training, and deployed halfway around the world to fight a kind of war that, if not new, was new to the soldiers of Task Force 1-34 Armor.\ Difficult as these transformations were, the combat soldiers of the Task Force in some ways had an easier time adapting than the staff. The essence of the line soldiers' mission remained closing with and destroying the enemy. Their additional tasks of supporting the local government and winning the trust of the local people were subordinate to and in some ways a natural outgrowth of their ability to provide security. The battalion staff had to change its entire approach to combat, shifting its focus from battle-tracking enemy tank platoons and infantry squads who fought in plain sight to identifying and locating an insurgent enemy who hid in plain sight. This much more difficult change demanded an entirely different way of thinking about combat-a different level of professional knowledge about a different kind of war. The enemy we faced could only be defeated if we knew both his name and his address-and, often, the addresses of his extended family as well. Understanding tribal loyalties, political motivations, and family relationships was essential to defeating the enemy we faced, a task more akin to breaking up a Mafia crime ring than dismantling a conventional enemy battalion or brigade. "Link diagrams" depicting who talked with whom became a daily chore for a small intelligence staff more used to analyzing the ranges of enemy artillery systems.\ The book that follows pays ritual obeisance to the importance of intelligence in counterinsurgency operations, and to the canard that "To defeat an insurgency you have to know who the insurgents are-and to find that out, you have to win and keep the support of the people." All true, truer than I knew at the time I wrote it. But the task of winning and keeping the support of the population is far more complex than I had understood. In the following pages, I note that the British did a better job of gaining the trust of the Malay population, but I don't properly emphasize that when the insurgency began they had been in the country for well over a century, developing long-term relationships and cultural awareness that bore fruit in actionable intelligence.\ The United States is working diligently in Iraq, as it did in Vietnam, to improve the lives of the people. Dollars are bullets in this fight; the Commander's Emergency Response Program (CERP), which provides field commanders funds to perform essential projects, wins hearts and minds twice over-once by repairing infrastructure, and again by employing local citizens who are otherwise ready recruits for the insurgents. CERP is helping with the painstaking process of building relationships with the Iraqi people, resulting in some intelligence from those we help-but not enough, not yet.\ One of the most frustrating aspects of the war on the ground in Iraq is responding to the scene of an attack, whether on U.S. or Iraqi security forces, with the sure knowledge that at least some of the bystanders have critical information on those responsible, but being unable to obtain that information from them. The people know the insurgents; they are often tied to them through blood or marriage or long association. The combination of these bonds and the likelihood that they will be killed in the night if they are seen talking to security forces in the day all too often intimidates those who genuinely want peace in Iraq, but see no way to achieve it at a bearable personal cost. Winning the Iraqi people's willingness to turn in their terrorist neighbors will mark the tipping point in defeating the insurgency. Those who contend that "American forces have lost the support of the Iraqi population and probably cannot regain it" are incorrect; in fact, the majority of the Iraqi population prefers the American vision of a democratic and free Iraq to the Salafist version of Iraq as Islamic theocracy. The key challenge is empowering the intimidated majority to enable Iraqi and American security forces to eliminate the criminal insurgents.\ The Irreplaceable Role of Local Forces\ When I wrote this book, I underestimated the challenge of adapting an army for the purposes of defeating an insurgency while simultaneously maintaining the army's ability to fight a conventional war. I also understated the importance of local forces in defeating an insurgency and the difficulty of raising, training, and equipping them. Creating reliable, dedicated local forces during the course of an insurgency that targets not just the local soldiers and police but also their families truly is a task as difficult as "eating soup with a knife."\ Local forces have inherent advantages over outsiders in a counterinsurgency campaign. They can gain intelligence through the public support that naturally adheres to a nation's own armed forces. They don't need to allocate translators to combat patrols. They understand the tribal loyalties and family relationships that play such an important role in the politics and economies of many developing nations. They have an innate understanding of local patterns of behavior that is simply unattainable by foreigners. All these advantages make local forces enormously effective counterinsurgents. It is perhaps only a slight exaggeration to suggest that, on their own, foreign forces cannot defeat an insurgency; the best they can hope for is to create the conditions that will enable local forces to win it for them.\ In their turn, however, foreign forces have much to offer local forces battling an insurgency. Western armies bring communications packages, training advantages, artillery and close air support, medical evacuation, and Quick Reaction Forces that together contribute dramatically to the confidence, morale, and effectiveness of the local forces, especially when trainers are embedded with the locals.\ The fact that the insurgents often attack local forces suggests that they realize how essential those forces are. Task Force 1-34 Armor worked diligently to mentor the local police force and two battalions of the Iraqi National Guard during its year in Khalidiyah. Recruiting, organizing, training, equipping, and employing these forces often appeared to be an uphill fight, as the Iraqi leadership both wanted and resented American leadership and logistical and financial support. Building trust through joint operations and shared risks ultimately resulted in some intelligence sharing, but the task of creating reliable forces that could independently guarantee local security was incomplete when the Task Force passed responsibility for these units to its follow-on force, the Currahees of Task Force 1-506 Infantry. The effort to raise, train, and equip these forces is likely to take much time and energy, but it could not be more important. The British forces in Malaya had earlier and better success with this process than did the Americans in Vietnam, with the possible exception of the Marines' Combined Action Platoon program in I Corps. Some of the lessons of the British and Marine experiences may be of use today as the United States increasingly turns its attention to the task of creating Iraqi security forces that can defend Iraq against both internal and external threats. Their success is the key to unlocking victory in Iraq-victory for, and by, the Iraqis.\ Innovation under Fire\ This book suggests that tactical leaders in the field can spur innovation that, when accepted by higher commanders, dramatically reshapes an army in combat. The experience of the U.S. Army in Iraq certainly supports that contention. Tank battalions, which just weeks previously had been required to execute missions no more politically complicated than "Attack" and "Defend," learned while in combat how to conduct Area Denial operations and Special Forces-style raids even as their battalion leadership conducted political negotiations with local leaders and trained and equipped Iraqi police and National Guard forces. Task Force 1-34 Armor learned to integrate Civil Affairs, Psychological Operations, and Counterintelligence Teams into its daily counterinsurgency operations. Linking up in theater and inventing doctrine on the run, these Counterinsurgency Teams were essential to the success of the battalion in winning the hearts and minds of the good guys-and of uncovering, capturing, and killing the bad ones.\ The United States Army has taken remarkable strides to adapt to the demands of counterinsurgency in Iraq in a process it calls the "Modular Army." Stepping away from the 15,000-soldier division as the center of gravity of the army, this program creates more nimble 4000-soldier Units of Action able to operate independently over a wide area. The army is also taking steps to increase the numbers of soldiers with much-needed special skills including the counterintelligence and civil affairs soldiers that Task Force 1-34 Armor put to such good use in Khalidiyah. Programs to recruit additional Arabic speakers are underway in both the Active Army and in the National Guard, adding another essential weapon to the counterinsurgency capability of the nation. Much more remains to be done as the army creates a force capable of the cultural and linguistic sophistication necessary to defeat a very capable enemy.\ Winning the Long War: The Integration of National Power\ The army is adapting to the demands of counterinsurgency in Iraq at many levels, from the tactical and operational through the training base in the United States. However, Iraq is but one front in a broader war against Salafist extremists dedicated to eliminating Western influence from the Islamic world; winning the struggle may take decades. There is a growing realization that the most likely conflicts of the next fifty years will be irregular warfare in an "Arc of Instability" that encompasses much of the greater Middle East and parts of Africa and Central and South Asia. To cope more effectively with the messy reality that in the twenty-first century many of our enemies will be insurgents, America's armed forces must continue to change.\ The 2005 Quadrennial Defense Review specifically evaluates the ability of the Department of Defense to prevail in irregular warfare. However, the fight to create a secure, democratic Iraq that does not provide a safe haven for terror is not primarily a military task. Counterinsurgency requires the integration of all elements of national power-diplomacy, information operations, intelligence, financial, and military-to achieve the predominantly political objectives of establishing a stable national government that can secure itself against internal and external threats. Britain was able to employ all of these elements of power remarkably well in Malaya; the process of integration took the United States longer in Vietnam.\ Final victory in today's fight depends upon the integration of the nations in the Arc of Instability into the globalized world's economic and political system. The army is working hard to adapt to the challenge of the global insurgency. The other departments of the federal government, and governments throughout the entire world, are steeling themselves for a protracted struggle. They also must adapt themselves to prevail in this fight, creating an operational capability to influence the actions of other nations and of subnational groups in the Arc of Instability.\ Much of the burden of that struggle will continue to be borne by the young men and women of the American armed services and by their local force comrades in arms. It was truly an honor and an inspiration to serve in Iraq with some of the finest soldiers our country has ever produced. Their spirit of selfless service and determination to fight so that others can live in freedom should humble all of us. It is to them that I dedicate this edition.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife by John A. Nagl Copyright © 2005 by John A. Nagl. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Foreword1How armies learn32The hard lesson of insurgency153The British and American armies : separated by a common language354British army counterinsurgency learning during the Malayan emergency, 1948-1951595The empire strikes back : British army counterinsurgency in Malaya, 1952-1957876The U.S. army in Vietnam : organizational culture and learning during the advisory years, 1950-19641157The U.S. army in Vietnam : organizational culture and learning during the fighting years, 1965-19721518Hard lessons : the British and American armies learn counterinsurgency1919Organizational culture and learning institutions : learning to eat soup with a knife213

\ Washington Post "[A] highly regarded counterinsurgency manual."\ — Michael Schrage\ \ \ \ \ \ Times (UK)"The success of DPhil papers by Oxford students is usually gauged by the amount of dust they gather on library shelves. But there is one that is so influential that General George Casey, the US commander in Iraq, is said to carry it with him everywhere. Most of his staff have been ordered to read it and he pressed a copy into the hands of Donald Rumsfeld when he visited Baghdad in December. Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife (a title taken from T.E. Lawrence — himself no slouch in guerrilla warfare) is a study of how the British Army succeeded in snuffing out the Malayan insurgency between 1948 and 1960 — and why the Americans failed in Vietnam. . . . It is helping to transform the American military in the face of its greatest test since Vietnam. "\ — Tom Baldwin\ \ \ \ eedings of the United State Naval Institue"An extremely relevant text. Those interested in understanding the difficulties faced by Coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, or who want to grasp the intricacies of the most likely form of conflict for the near future, will gain applicable lessons. [Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife] offers insights about how to mold America's armed forces into modern learning organizations. As the Pentagon ponders its future in the Quadrennial Defense Review, one can only hope that Nagl's invaluable lesson in learning and adapting is being exploited."\ — Frank G. Hoffman\ \ \ \ \ \ Wall Street Journal"Brutal in its criticism of the Vietnam-era Army as an organization that failed to learn from its mistakes and tried vainly to fight guerrilla insurgents the same way it fought World War II. In [Learning to Eat Soup With a Knife], Col. Nagl, who served a year in Iraq, contrasts the U.S. Army's failure with the British experience in Malaya in the 1950s. The difference: The British, who eventually prevailed, quickly saw the folly of using massive force to annihilate a shadowy communist enemy. . . . Col. Nagl's book is one of a half dozen Vietnam histories -- most of them highly critical of the U.S. military in Vietnam -- that are changing the military's views on how to fight guerrilla wars. . . .The tome has already had an influence on the ground in Iraq. Last winter, Gen. Casey opened a school for U.S. commanders in Iraq to help officers adjust to the demands of a guerrilla-style conflict in which the enemy hides among the people and tries to provoke an overreaction. The idea for the training center, says Gen. Casey, came in part from Col. Nagl's book, which chronicles how the British in Malaya used a similar school to educate British officers coming into the country. 'Pretty much everyone on Gen. Casey's staff had read Nagl's book,' says Lt. Col. Nathan Freier, who spent a year in Iraq as a strategist. A British brigadier general says that 'Gen. Casey carried the book with him everywhere.'"\ — Greg Jaffe\ \ \ \ \ \ Armor"As the United States enters its fifth year of the war on terror, military leaders are conducting low-intensity and counter-insurgency operations in several different areas around the world. Of the different books produced on this subject, LTC John Nagl's Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife is an absolute must for those who want to gain valuable insight on some of the hard lessons of fighting an insurgency before actually getting on the ground. The book expertly combines theoretical foundations of insurgencies with detailed historical lessons of Malaya and Vietnam to produce some very profound and topical implications for current military operations. The true success of the book is that Nagl discusses all of these complex issues in an easy-to-follow and straight-forward manner. . . . I read this book upon returning from my tour in Iraq after commanding a company on the ground for a year. I was amazed at how insightful and 'true' the conclusions were and wished that I had read it before I deployed."\ — Nick Ayers\ \ \ \ \ \ Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute"Nagl, currently a Military Assistant to the Deputy Secretary of Defense, focuses on organizational culture as the key to defeating insurgencies: successful militaries learn and adapt."—"Recommended Reading on Counterinsurgency," Nathaniel Fick, Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute\ — Nathaniel Fick\ \ \ \ \ \ Military Review"The capacity to adapt is always a key contributor to military success. Nagl combines historical analysis with a comprehensive examination of organisational theory to rationalise why, as many of his readers will already intuitively sense, 'military organisations often demonstrate remarkable resistance to doctrinal change' and fail to be as adaptive as required. His analysis is helpful in determining why the U.S. Army can appear so innovative in certain respects, and yet paradoxically slow to adapt in others."—Nigel R F Aylwin-Foster, Military Review\ — Nigel R F Aylwin-Foster\ \ \ \ \ \ Philadelphia Inquirier"One key army text is Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife by Lt. Col. John Nagl, which focuses on counterinsurgency lessons from the 1950s war in Malaya and from the Vietnam War. The title phrase was used by Lawrence of Arabia in describing the messy and time-consuming nature of defeating insurgents. Nagl focuses on the ability of armies to learn from mistakes and adapt their strategy and tactics—skills in which he finds U.S. forces lacking. He shows how the British in Malaya were nimble enough to defeat a communist insurgency, while the U.S. military in Vietnam clung to a failing doctrine of force. Sadly, the Pentagon had not absorbed such insights before invading Iraq. Nagl himself says he learned a lot more during a one-year tour in Iraq. His ideas, if applied back in mid-2003, might have checked the growth of the Sunni insurgency in Iraq and prevented Sunni Islamists from provoking a civil war with Iraqi Shiites. It may be too late for the Army's new doctrine to stop Iraq from falling apart....It's past time to make Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife required reading at the White House."\ — Trudy Rubin\ \ \ \ \ \ Michael Leeden"As the Baker/Hamilton club considers America's options in the Middle East, its members would do well to browse currently hot books on counterinsurgency [including] Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam...Stimulating, thoughtful and serious."\ — The Jerusalem Post\ \ \