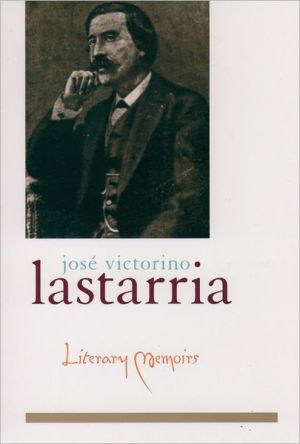

Literary Memoirs

Novelist, scholar, journalist, statesman, and leading member of Chile's "Generation of 1842"--an intellectual movement so named for the founding of the National University--José Victorino Lastarria (1811-1888) lived his life at the forefront of nineteenth-century Chilean and Spanish American culture, literature, and politics. Recuerdos Literarios (or Literary Memoirs) is his masterpiece, encompassing the candid memories of a tireless activist, both the creative and critical sensibilities of...

Search in google:

Novelist, scholar, journalist, statesman, and leading member of Chile's "Generation of 1842"—an intellectual movement so named for the founding of the National University—José Victorino Lastarria (1811-1888) lived his life at the forefront of nineteenth-century Chilean and Spanish American culture, literature, and politics. Recuerdos Literarios (or Literary Memoirs) is his masterpiece, encompassing the candid memories of a tireless activist, both the creative and critical sensibilities of an influential Latin American early modernist, and an eyewitness account of the development of Chilean literature and historiography. An ardent, eloquent participant in every defining artistic and ideological debate in Chile during the formative mid-1800s, Lastarria recorded his epoch as closely as he did his own origins, education, ambitions, and career. Sometimes reminiscent of Montaigne's essays, Eça de Quieroz's journalism, or Barbusse's didactic convictions, Literary Memoirs is an engrossing account of Chile's newly ordained nationhood.This addition to Oxford's prestigious Library of Latin America series is more than a retelling of things past; it is an informed yet informal testament to the idea of chilenidad (or "Chileanness") and a detailed portrait of one of Chile's cultural architects. For this new edition of Literary Memoirs, Frederick M. Nunn's introduction presents an informative historical background and R. Kelly Washbourne's translation carefully preserves Lastarria's form and content.Publishers WeeklyFrom Oxford University Press's Library of Latin America comes a significant but dry work about the formation of Chile's literary culture. Born in 1817, the year before Chile won its independence from Spain, Lastarria quickly rose through university ranks and became actively involved in the development of the country's culture. In his introduction, Nunn points out that, unlike most of the Latin American countries that broke away from Spain in the 19th century, Chile managed to create a stable government within the first 15 years of its independence. Nonetheless, Lastarria makes a point of reminding his readers that the transition was anything but smooth. In fact, the author was prompted to write his memoirs because Chilean historians only a generation younger than himself were already misrepresenting the country's history and misattributing its achievements. Lastarria sets the record straight: he provides a blow-by-blow account of the founding of the National University and the reform of the education system (which he helped move away from peripatetic, monastic style by promulgating less disciplinarian classroom techniques developed in France), and he recounts how writers began to develop the literary culture that eventually laid the path for future Nobel laureates Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda. Lastarria's conscientious detailing of facts is a boon to scholars, but his writing is parched; though his political tracts are fiery enough, their melodramatic poetics are likely to put off modern readers. (Dec.) Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ PART ONE\ 1836-1849\ \ \ I\ \ \ The attention of contemporary historians is constantly drawn to the literary movement that took place in our country in 1842, and they rightly consider it the earliest impetus to the portentous progress made in Chilean letters in the thirty-five years that have elapsed since that memorable date.\ The stimulus of that year has expanded in regular, concentric circles, as if intellectual thought were an ocean whose surface had absorbed a vertical impact. In 1812, in the Antilles sea, in the early hours of the night fell a giant meteorite, an asteroid that lit up the horizon like the sun, bursting through the atmosphere with a terrifying roar, and leaving a trail many degrees in intensity, which marked its course a quarter hour after it had plunged into the immense gulf. After a few hours, the shock wave, which had rippled in ring after ring out from the point of impact on the water, reached the fortresses of Cartagena, rising against the walls to an admirable height, and unleashing the effects of a storm on the boats. A similar effect came in the wake of the phenomenon that, in a fit of patriotic ardor, was stirred up in national thought in 1842, the difference being that the waves that still continue in succession will not abate as long as said thought is not confined by the hindrances of despotism or by the enslavement of the spirit.\ Yet contemporary historians have not, by and large, been exact when they describe this literary movement. The account of events isnot useful, nor does it meet its objectives, if it is not exact. On the contrary, if it does not mislead future historians, it saddles them with the arduous task of uncovering the truth. An event can be seen in a different light by contemporaries, and it can be appraised, likewise, by different criteria; but facts are facts, and in narrating them, one may not alter them or attribute them to causes or people that have not participated in them, nor attribute to the undeserving the responsibility or the glory attendant to them.\ And all of this is exactly what happens habitually when the origins of our literary trajectory are recalled. In lightweight works, destined to pass like the leaves of autumn, a memory may be imprinted without doing research, or even reminiscence; yet if one does likewise with a serious work, its rectification is a duty, the fulfillment of which, rather than being offensive, should be agreeable to him who has invited it.\ One work of this nature, the Historia de la administración Errázuriz, ["History of the Errázuriz Administration"] inspired this reflection. In the hopes of setting right its information, let us put our literary memoirs in order, with a view to testify in the judgment of the evolution of Chilean thought. In the fine outline of the movement of parties from 1823 to 1871, which serves as an introduction to the work, the author puts a popular face on the 1842 literary movement, implying that "the youthful independent society began to joyfully contemplate its own image in the early efforts of a lively, vigorous literature." This production appeared in El Semanario, whose publication he attributes not to its founder, whose name he forgets, nor even to its rightful authors, but to some of its collaborators and people that had no share in it, like Mrs. Marín de Solar, don Carlos and don Juan Bello, and don Francisco de Paula Matta, to whom Mr. D. Arteaga Alemparte also attributes an active role in this literary movement, which in the biography that he wrote of this interesting young man, who died regrettably in the flower of his youth, he alleges began with El Semanario.\ Both writers, like many others, impute the movement to El Semanario ["The Weekly"], utterly dispensing with writers previous to this newspaper that had produced it; we can rest assured that neither was the former movement popular, nor was it El Semanario's doing. That publication was born of a preceding stimulus, without even reaching a readership sufficient to keep the publication solvent; nor could society contemplate its image in the output of a lively, vigorous literature which could not yet exist, save for in meticulous, artless articles. It is far less plausible to ascribe the impulse, calculated by the patriotism of a few, and continued steadfastly, to the memory preserved of the era of attempts at a representative system, and to the influence scientific institutions exercised prior to 1830 over young souls, as the author of the Historia maintains. The author is correct in asserting that our society's pulse could barely be felt, though "the dejection and prostration of a nation are never as thoroughgoing as the high priests of authoritarian dogma would have it." But he has no historical data for supporting his belief that the movement was the work of influences that by that point were nonexistent, nor the "forces or means that the nation, in its immobility, had piled up by degrees to refashion itself"; for there was neither this stockpiling nor did the society refashion itself, but on the contrary it held out for many years against any reforming, and perhaps resists it to this day.\ The 1842 literary movement did not originate in social influences, nor in previous historical events, and supervened as a virtually individual reaction, which it had to produce on its own and without resources the event that it would deliver, through all manner of political and social obstacles. Had it not been thus, if social history had set the stage for the movement, the individual action that promoted it would have had an expeditious and unobstructed path. On the contrary, the event has stalled many times, and has had but a sporadic existence, until, in the span of thirty-five years, it gradually has consolidated our civic responsibility, while through the practice of freedom, the spontaneous cooperation of social elements continued its normal course. Then a society emerged that, although still young, has fairly well-defined feelings and ideas, needs and interests for seeking its expression in a nascent literature, but whose characteristic features are already clearly delineated.\ Thus, it is not inopportune to look back frequently upon the age in which our literary movement began; and it is vital to ascertain accurately its historical character and the moment of its appearance. To that end we need to recall the earliest attempts made in 1826 to revise scholarship on the subject, efforts that had foundered on the reefs of old routine, which after ten years appears once again triumphant next to the colonial reaction that had grown entrenched in the backward-thinking party in 1830. The year 1836 is notable in our history for the intellectual and moral lethargy into which the political situation had thrust us. That is the supreme moment of the crisis, and there begins the convalescence of our spirit, in which, fortunately, we took some part, a fact that authorizes us to set down these memoirs.\ The historians state clearly that for the current generation, which reaps the harvest of the last thirty years' efforts, it will be of no account to know what part that was; but, to be frank, the author of these memoirs cannot accept that indifference, nor should he, for even when he holds no claim to anyone's gratitude, he does have the right to reject the shroud he does not wish to wear, seeing that he is alive: the shroud of oblivion. Will one be taken amiss for wishing not to be forgotten? There is no offense in that. What is bothersome is that someone is candid enough to be omnipresent; but that candor disappears when one claims his rightful place, against those who are minded to dislodge him.\ \ \ Chapter Two\ II\ \ \ Taking as a guidepost the historical date that Mr. Gay relates in volume VII of his Historia de Chile, the organizing efforts of all branches of government that General Freire's administration undertook in 1823 were directed preferentially to public education. The Instituto Nacional received a yearly endowment of 25,000 pesos in order to fulfill the duties of the Instituto Normal de Preceptores ["Teacher Training School"], which attributed to it by the 10 June senatus consultum of that year, with a view to it serving as the standard in public education and as a model for all other teaching institutions yet to be founded.\ The Instituto, which had been reestablished in 1819 during O'Higgins' administration, and reorganized by Cienfuegos, the governor of the bishopric, remained in 1823 a university center, in keeping with decreed academic laws and by-laws. The Institute was divided into three sections, one for scientific instruction, the second for engineering instruction, and the third was a museum of instruments for the study of the experimental sciences; its special code of conduct, the work of don Juan Egaña, subjected its control to the holy guidance of religious principle.\ Moreover, a 10 December decree that same year created the Academia Chilena ["Chilean Academy"], which, as a main organ of the Instituto, likewise had three sections: moral and political science, physical science and mathematics, and literature and the arts.\ In 1824, on the occasion of the organization of tribunals and courts and the promulgation of the Rules of Justice, special attention was paid to legal studies; the profession of lawyer became, due to the diligence with which the aspirants were trained, and the importance of government positions in the administration of justice that were obtained with that degree, the profession that gave the Instituto Nacional the supremacy with which the rules and regulations had wished to invest it, giving it the character of a university for cultivating other studies, which in fact were eliminated.\ This fact was a natural result of the new organization of the administration of justice, for which public opinion had clamored with great perseverance in those days as the meeting of an urgent and supreme need. The O'Higgins administration had not been able to carry out this enterprise successfully, and although it had abolished some of many special tribunals that existed, it left standing, with slight alterations, the judicial organization and procedures from colonial times, complete with all their shortcomings and slowness. To ensure enforcement of national laws, which the lawyers tried to evade whenever convenient to their defense plan, invoking old Spanish laws, the penalty of suspension of their office was imposed upon them for cases in which they committed this misdeed, but such an objective was not reached; in order to curb raids on property, which occurred time and time again with alarming frequency, a decree by the Supreme Delegate Director, don Hilarión de la Quintana, had sanctioned the death penalty for any individual who robbed an amount in excess of four pesos, and a sentence of two hundred lashes and six years of hard labor if the value was less, in which case the briefest military judgment would suffice. Shortly thereafter, the court-martial having been disbanded, it was ordered that the mayors enforce said punishments, laying aside customary formulas for criminal sentencing, with but a summary briefing that had to be submitted for review to the chamber of justice, which was obliged to settle the matter the same day.\ This arbitrariness, entrenched as a normal order, was what alarmed the 1823 patriots; and although property raids had not diminished, and there were spells during which, as always happens, they proliferated with irritating and daring frequency, the legislators attached less importance to penal severity than to a judicious administration of justice that brought together procedural promptness and uprightness, safeguards sufficient to bring arbitrariness to a halt; this ran contrary to what lawmakers thought fifty years later, when in 1876 they returned to Director Quintana's system to punish robbery.\ Of all the reforms that were being adopted around that time, the judicial one was the most important, for since it affected private interests most immediately, it was the one that most insistently and vigorously rallied public opinion. These circumstances, on the one hand, and the fact the new organization of the independent country was owed, and rightly, to the men of letters, more than to military men who had guaranteed independence, gave the profession of lawyer such preeminence that not only was it seen as the only and most enviable career, but also all plans advanced to establish public education on a broader, more comprehensive base were scuttled. Thus the Instituto Nacional was eventually reduced to a law school, and in lieu of the Academia Chilena, which by decree of 1823 completed its organization, the old Academy of forensic practice, which was constituted definitively on 29 January 1824 and continued in operation, as per its by-laws, until a short time ago it was disestablished and replaced by a regular University class, certainly to no advantage.\ Thus stood the situation in 1826, but legal studies, Latin grammar, and philosophy, which had been their training, had not gone beyond the plan and ways in which they were done in the Colonial era; this contratemps, so contrary to the aspirations of those who had intended a reform of public education, was a death-dealing blow to its efforts. The above-mentioned historian records this fact thus: "Though the program (at the Instituto)"—he states—"was much more extensive, it still did not completely satisfy the avidity of those generous patriots. The classes labored under the lingering Scholasticism of the Middle Ages, whose teaching method was overburdened with pointless and at times ridiculous concerns; they wanted to introduce into the courses a more fitting direction, one more harmonious with the modern Zeitgeist. With this aim, the administration tried to place at the helm of the Instituto a person whose studies might have been completed with that intellectual orientation, and brought Mr. Charles Lozier, then occupied in drawing up the geographic map of Chile."\ General Freire's administration had brought from Buenos Aires this wise Frenchman to assume the headship of the engineering education section, which had been set up at the Instituto; but given that the scientific journey to which Mr. Dauxion Lavaysse had been commissioned had not yielded the prompt outcome that was expected, the implementation of that curricular form was postponed, and Lavaysse was replaced by Lozier.\ Lavaysse was hired to study the country's natural history and to compile its statistics, indicating navigable rivers, suitable places for building factories, ports, channels, and roads—which had to be made to facilitate commerce, the means of spurring agriculture and adaptable lands for growing the basic industrial stuffs; and since the first foray he made into the north produced no immediate results, he was thought incompetent and lost his post, remaining in the country continuously until in 1829, while living in the Liceo de Mora ["Mora Secondary School"], where he had taken lodging. We students found him dead one morning in his own bed, after a few days of illness.\ Mr. Lozier received on 20 December 1823 the same assignment, the task of drafting the geographic map of Chile, having for his collaborator the colonel of engineers, don Alberto d'Albe, who had been commissioned especially to marshal military figures and demarcate suitable localities for national defense. Mr. Gay considers that, in light of the Lavaysse episode, Mr. Lozier erred in committing to carrying out particulars that would require a large number of years, with no hope of executing his duties to the satisfaction of the many Chileans who feel that they can perfectly well, and in little time, perform observational tasks like the ones in question, which are invariably long and difficult, and which commonly are quite far from covering the large financial outlay they occasion. If the like-minded historian has fallen victim to similar unthinking, baseless demands, in spite of his assiduous devotion to the study of the natural history of Chile; and if the wise Pissis is in the same situation right now, a man for whom twenty-eight years have not sufficed to consummate his grand work that Mr. Lozier had undertaken in 1826, one can imagine the disillusionment into which in 1826 the governors fell, men who had imagined they would conduct in short order the scientific surveys they needed to know about their country, when after three years nothing more than the beginnings of such a formidable undertaking had gotten underway.\ Therefore they scotched the project, and preferred to employ Mr. Lozier in curricular reform in order to wrest the Instituto from the grip of its peripatetic routine and widen its sphere of action, as previously was sought through the senatus consultum that gave it the character of a standard institution of broad-based education. Don José Miguel Infante, who was the one who with the most intelligent and innovative spirit had sought to elevate public education, was responsible for the change, since as General Freire's replacement in the supreme magistracy, he reorganized the Instituto on 20 February 1826, entrusting its headship to Mr. Lozier, and empowering the new rector to make all innovations and reforms he deemed appropriate, to propose new teaching methods, and to organize its administration to the students' best advantage.\ Mr. Lozier was unquestionably the most appropriate man under the circumstances to give expression to the interim Supreme Director's decree. He showed clearly that his aspirations lay in giving education a positive grounding by organizing a complete course in mathematical and physical sciences, a required course for all students, even those whose area of concentration was the legal field. These were students for whom some science classes were developed that were to a certain degree adequate to broaden their scope of knowledge. Meanwhile he made a priority of the overall reform plan, especially of the teaching methods in the humanities and law, and after early favorable results obtained in the sciences course that he himself had overseen beginning in March 1826, he organized with the most advanced students and the professors, a society for studying and disseminating elementary teaching methods unknown in the country, and which were important to circulate if curricular reform was to be taken seriously. This society, inspired by its director's enthusiasm, devoted itself assiduously to free education from its monastic rut, which rendered it sterile, and began publishing El Redactor de la Educación ["The Drafter of Education"], a sixteen-page literary journal consisting of translated and excerpted articles on a given topic, a publication that printed six issues up to the moment in which the innovative rector's job ended violently.\ The partisans of routine, in other words, the common run of educated men, rebelled against Mr. Lozier's innovations, and their criticism and scorn spread to the students, who, freed from the whip, which had been outlawed, and from austere treatment at the hands of the schoolmasters, took for weakness the new rector's familiar, good-natured manner. Swayed by pernicious promptings, they staged an all-out rebellion against Mr. Lozier, and completely disrupted the Instituto.\ Mr. Gay, regretting the reform's failure, feels that had it been adopted gradually, and not been as sweeping and large-scale, it would have reached fruition unopposed; nevertheless he allows that: "Unfortunately Mr. Lozier's ideas with respect to education clashed head-on and excessively against deep-seated custom, habit, tradition, and memory that constituted the country's very redoubtable concerns."\ Thus, they prevailed, for the student revolt gave the new president of the republic, Mr. Eyzaguirre, leeway to repeal the Infante decree at the end of 1826, reorganizing the Instituto and placing it under the tutelage of the most rabid ambassador of colonial tradition, the Presbyter don Juan Francisco Meneses. Fortunately, he could not contain the movement begun by Mr. Lozier, destroying preparations already in place, which expedited for the partners in reform the establishment of a new course in 1827. Don Pedro Fernández Garfias instituted the teaching of Latin in the Spanish language, following the Ordinaire method; don José Miguel Varas and don Ventura Marín began to teach in the same language diverse branches of experimental philosophy. Don Andrés Gorbea took over from Lozier in teaching pure mathematics and physics.\ The following year, ideas on curricular reform, which until then had not been formulated systematically, caught the public's attention when presented strikingly in the Chilean Secondary School Study Plan, which don J.J. de Mora published; the young professors at the Instituto, with honorable emulation, were the first to galvanize efforts so that their institution did not lag behind in either the path of practical innovation, that in which the new plan had been proposed in 1829, or the Colegio de Santiago, which was founded in 1830 to rival the Liceo.\ This movement died out before long with the elimination of these latter two institutions and with the triumph of the political reaction, which strengthened, organized a conservative administration, and by 1836 came to bestride all spheres of social life.

Series Editors' General IntroductionNote on the Author, the Editor, and the TranslatorChronology of Jose Victorino Lastarria SantanderIntroductionWorksContentsLiterary Memoirs1

\ Publishers Weekly\ - Publisher's Weekly\ From Oxford University Press's Library of Latin America comes a significant but dry work about the formation of Chile's literary culture. Born in 1817, the year before Chile won its independence from Spain, Lastarria quickly rose through university ranks and became actively involved in the development of the country's culture. In his introduction, Nunn points out that, unlike most of the Latin American countries that broke away from Spain in the 19th century, Chile managed to create a stable government within the first 15 years of its independence. Nonetheless, Lastarria makes a point of reminding his readers that the transition was anything but smooth. In fact, the author was prompted to write his memoirs because Chilean historians only a generation younger than himself were already misrepresenting the country's history and misattributing its achievements. Lastarria sets the record straight: he provides a blow-by-blow account of the founding of the National University and the reform of the education system (which he helped move away from peripatetic, monastic style by promulgating less disciplinarian classroom techniques developed in France), and he recounts how writers began to develop the literary culture that eventually laid the path for future Nobel laureates Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda. Lastarria's conscientious detailing of facts is a boon to scholars, but his writing is parched; though his political tracts are fiery enough, their melodramatic poetics are likely to put off modern readers. (Dec.) Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalThis volume is the latest in the important Oxford series "Library of Latin America," which is designed to publish English translations of important works of major 19th-century Latin American authors. In this particular text, Lastarria, one of Latin America's most influential intellectual and political figures (a founder of Chile's "Generation of 1842"), critically examined the intellectual life and literature of Chile. Frederick Nunn, a noted historian of Chile, provides a simulating and informative introduction about Lastarria and 19th-century Chile. A delightful read, in part because it is very much a personal memoir of the author, this book is an important volume for academic libraries with Latin American collections.--Mark L. Grover, Brigham Young Univ. Lib., Provo, UT Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \