Losing My Cool: How a Father's Love and 15,000 Books Beat Hip-Hop Culture

A pitch-perfect account of how hip-hop culture drew in the author and how his father drew him out again-with love, perseverance, and fifteen thousand books.\ Into Williams's childhood home-a one-story ranch house-his father crammed more books than the local library could hold. "Pappy" used some of these volumes to run an academic prep service; the rest he used in his unending pursuit of wisdom. His son's pursuits were quite different-"money, hoes, and clothes." The teenage Williams wore...

Search in google:

A pitch-perfect account of how hip-hop culture drew in the author and how his father drew him out again-with love, perseverance, and fifteen thousand books. Into Williams's childhood home-a one-story ranch house-his father crammed more books than the local library could hold. "Pappy" used some of these volumes to run an academic prep service; the rest he used in his unending pursuit of wisdom. His son's pursuits were quite different-"money, hoes, and clothes." The teenage Williams wore Medusa- faced Versace sunglasses and a hefty gold medallion, dumbed down and thugged up his speech, and did whatever else he could to fit into the intoxicating hip-hop culture that surrounded him. Like all his friends, he knew exactly where he was the day Biggie Smalls died, he could recite the lyrics to any Nas or Tupac song, and he kept his woman in line, with force if necessary. But Pappy, who grew up in the segregated South and hid in closets so he could read Aesop and Plato, had a different destiny in mind for his son. For years, Williams managed to juggle two disparate lifestyles- "keeping it real" in his friends' eyes and studying for the SATs under his father's strict tutelage. As college approached and the stakes of the thug lifestyle escalated, the revolving door between Williams's street life and home life threatened to spin out of control. Ultimately, Williams would have to decide between hip-hop and his future. Would he choose "street dreams" or a radically different dream- the one Martin Luther King spoke of or the one Pappy held out to him now? Williams is the first of his generation to measure the seductive power of hip-hop against its restrictive worldview, which ultimately leaves those who live it powerless. Losing My Cool portrays the allure and the danger of hip-hop culture like no book has before. Even more remarkably, Williams evokes the subtle salvation that literature offers and recounts with breathtaking clarity a burgeoning bond between father and son.The Washington Post - Jabari AsimIt would be a shame if Williams's thoughtful comments about hip-hop, which deserve and undoubtedly will receive articulate response, detract attention from other equally engaging portions of Losing My Cool. For example, his portrait of his dad, an intensely private man, contains some of the most compelling writing about black fathers in recent literature on the subject. There is much to admire in Losing My Cool, and more to anticipate from Williams.

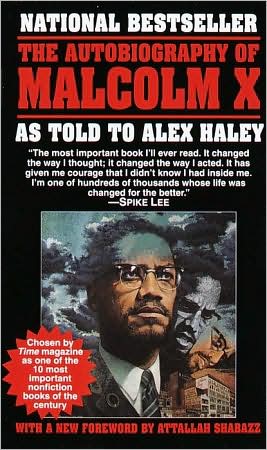

Chapter One\ The Discovery of What It Means to Be a Black Boy\ It was wintertime, early in the morning. I was in the third grade, standing on the rectangular asphalt playground behind Holy Trinity Interparochial School in Westfield, New Jersey, palming a tennis ball, waiting. Ned, nearsighted and infamous for licking the dusty soles of his penny loafers in the back of social studies class, was splayed against the cold orange brick wall of the school building. He had his head down and hands up, legs akimbo with his butt out, like a South American mule bracing herself to be searched by border patrol. “Not so hard!” he cried, glancing back over his shoulder through smudged Coke-bottle lenses.\ “Put your head down!” another boy yelled.\ “Fine, just do it and get it over with, then,” Ned muttered.\ “Head down!” the boy said. I wound my arm back and let fly a fastball that seemed to hang in the air for a second before rico- cheting from the small of Ned’s back like a Pete Sampras ace off some hapless ball boy at Wimbledon. Ned jerked upright and howled in pain. All my classmates screamed and high-fived me as the bell rang and we rushed to grab our book bags and line up in size order before our teachers came to lead us indoors. I was still the undisputed king of Butts-Up, I thought to myself as I pulled my Chicago Bulls Starter jacket over my uniform. Standing in line, waiting for the younger grades to file past, I began mumbling to myself bits of a song by Public Enemy, a song that my older brother had been playing at home and that had gotten stuck in my head that week like the times tables or the Holy Rosary. “Yo, nigga, yoooooo, nigga, yoooo-oooooo, niiiigga . . .” I repeated the refrain over and over under my breath, unthinkingly, as I relived in my mind’s eye the glorious coup de grace, the deathblow I’d just dealt Ned from over ten yards away—Blaow!\ “But you’re a nigger, too,” a voice said from behind me, and I half made out what I’d just heard, but not fully. I went on singing my song, which I couldn’t claim to understand on any level, but which somehow made me feel cool as hell, and that was all that mattered. The voice repeated itself, louder this time: “But you’re a nigger, too, Thomas, aren’t you?”\ “Huh?” I said, pivoting to see Craig standing there, his dirtyblond hair cut by his mother’s Flowbee into the shape of an upsidedown serving bowl, like a medieval friar without the bald spot. “What did you just say?”\ “You’re a nigger, too, right, so how can you say that?”\ “How can I say what?”\ “‘Yo, nigga, yo, nigga’; how can you say that when you’re a nigger, too, right?” My mother is white, my father black. They met in San Diego in the late 1960s. Both were entrenched on the West Coast front of what at the time was called the War on Poverty. After San Diego, they went up to Los Angeles. From L.A. they made their way north and my father pursued doctoral studies in sociology at the University of Oregon. In 1975, and over my maternal grandfather’s dead body, they were married in Eugene at the county courthouse. They had little money, fewer blessings, and plenty of love. Later, they moved again to Spokane and my mother, Kathleen, gave birth to their first child, Clarence, named for my father. From Spokane the family continually moved east: first to Denver, then to Albany, then to Philadelphia, and finally to New Jersey, where I was born in 1981.\ When I was one year old, my father switched professions and the family moved again, this time from Newark, where he had been running antipoverty programs for the Episcopal Archdiocese and my mother had been raising my brother and me, to Fanwood, a small suburb thirty minutes to the west on U.S. Route 22. Fanwood, like the space inside a horseshoe, is bordered on three sides by the much larger township of Scotch Plains, and these two municipalities by and large function as one. They share a train station and public school system and together act as a kind of buffer ground between wealthy Westfield to the east and poor Plainfield to the west. Riots and waves of white flight long ago left Plainfield a vexed cross between a legitimate inner-city ghetto—with all the requisite crime, poverty, and hopelessness that go with that—and an emergent middle-class suburb that in many ways resembles Westfield, except for the condition of the houses and the color of the residents. No such white flight occurred in Fanwood, Scotch Plains, or Westfield, although like so many small towns in New Jersey, they had their designated black pockets.\ When my parents first began searching in the area, real estate brokers only wanted to show them homes in Plainfield or on the redlined black sides of town. They said families like ours tended to prefer things this way, but my father, whom we call Pappy in a nod to his Southern roots, had led a childhood that was boxed in by formal segregation in Texas, and no longer could stand to be told where to live. Out of principle he said to the brokers thank you but no thank you, and insisted on seeing all listings. Reluctantly, they caved and the four of us settled into a three-bedroom ranch on Fanwood’s decidedly white side.\ It was a neighborhood of well-kept homes with yards that were flaired-up with inflatable IT’S A BOY! lawn signs, lighted holiday displays, and the occasional life-size Virgin Mary shrine. There were two main downtown areas in either direction of our house, with more pizzerias than banks or dry cleaners and, to Pappy’s lament, without a single bookstore between them. Our neighbors were what my parents called “ethnic whites,” and they tended to grow up, buy homes, have children, and die within a twenty-mile radius of where they had been born—a fact that always seemed to strike Mom and Pappy as bizarre. As a family, we did not fit in with these people, who often didn’t know what to make of us. Once when I was a very young boy, I was at the grocery store with my mother, misbehaving as little children do, when an older white woman walked by and said, “Ugh, it must be so tough adopting those kids from the ghetto.”\ Despite my mother’s being white, we were a black and not an interracial family. Both of my parents stressed this distinction and the result was that, growing up, race was not so complicated an issue in our household. My brother and I were black, period. My parents adhered to a strict and unified philosophy of race, the contents of which boil down to the following: There is no such thing as being half-white, for black, they explained, is less a biological category than a social one. It is a condition of the mind that is loosely linked to certain physical features, but more than anything it is a culture, a challenge, and a discipline. We were taught from the moment we could understand spoken words that we would be treated by whites as though we were black whether we liked it or not, and so we needed to know how to move in the world as black men. And that was that.\ Questions of the soul were less clear. My mother is Protestant, the daughter of an evangelical Baptist minister. My father is what he calls a Geopolitical-Existentialist-Secularist-Humanist-Realist, which really is just his way of saying he doesn’t put much stock in organized religion. Nevertheless, after very nearly being homeschooled, Clarence and I were enrolled in private Catholic schools for what my father described as “the superior levels of discipline” they offered in relation to the public schools nearby.\ Another factor in the decision was the day Clarence came home from School One, about a half-block away from our front door, dazed and unable to speak. He was in the second grade and my father had given him an oxblood leather briefcase. Apparently, this made him stand out among the other boys. So did his suntanned skin, which after the long hot summer was the color of maple honey; and his hair, which was styled in a large spherical Afro and which in his childhood was light brown with strands of blond and something like sherry in it: beautiful. My mother and sometimes my father would comb my brother’s Afro in the mornings with an orange tin can of Murray’s dressing grease and a black plastic pick. “You look distinguished now, son,” Pappy would say, and smile when he was finished with him, distinguished being the rarest and highest compliment in his vocabulary.\ Clarence was a quiet boy with thick hair, good muscle tone, and intelligent almond-shaped eyes beneath bushy brown eyebrows. That day at school a group of white children had cornered and taunted him on the yard, asking what a fucking monkey had to do with a briefcase. Either the other black students didn’t see this happen or they chose not to intervene. Pappy yanked Clarence from public school the next day. By the time I was old enough, being in class with our neighbors was not even an option.\ Unlike some children of mixed-race heritage, I didn’t ever wish to be white. I wanted to be black. One of the first adult books my parents gave to me, around age seven, was Alex Haley’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Often my mother would come into my room in the evening and discuss with me what I was reading. For several nights, I lay awake long after she had turned out the lights, haunted by the image of Malcolm’s father lying prone on the railroad tracks, his body torn in two and his cranium cracked open like a coconut husk. I didn’t want to resemble in any way whatsoever those men who did things like that to other men.\ It was a fortunate thing for me, too, that I didn’t want to be white. It was fortunate because I really didn’t have much choice in the matter. My parents were right: Around white kids, I simply was not white. Whatever fantasies of passing may have threatened to steal into my mulatto psyche and wreak havoc there were dispelled early on, when Tina turned around in her chair, flipped her bronze ponytail to the side, and asked me point-blank, and audibly enough for the whole classroom to hear, “Hey, why doesn’t your hair move like everyone else’s?”\ “It’s because I’m black,” I told her, and I wasn’t angry or embarrassed. It was just a fact, I felt, the way that she was husky or big-boned.\ Though we didn’t speak about it outright, I don’t think my brother, Clarence, ever wanted to be white, either. He just didn’t seem to see race everywhere around him like my parents and I did. Or if he saw it, he fled from it and didn’t want to analyze it or have to spend his time unraveling it. He didn’t want to be forced to make a big deal out of it. He was forgiving and trusting and found companions wherever they would be his. His two best friends were black, and he dated a quiet Asian girl for a spell during high school. Mostly, though, he fell in with a set of neighborhood white boys with lots of vowels in their surnames and little in their heads. These white boys were almost certainly the same ones who, years earlier, had demeaned my brother with racial epithets on that School One playground (the neighborhood is not that big). But Clarence never knew how to hold a grudge, and that was ages ago and these were his neighbors and they liked to do the things that he liked to do: ride bikes, ride skateboards, talk cars, smoke cigarettes, cut class, hang out. And they did take him in as one of their own, that’s true, although I could see even as a child that they did so without ever fully allowing him to rest his mind, to forget that he was black and that he was somehow other. Still, I can’t fault my brother for going the way he felt was most comfortable. He was a child of the late ’70s and ’80s; hip-hop hadn’t completely circumscribed the world he was formed in. I was a child of the late ’80s and ’90s, on the other hand. I went the other route.\ Not that it was always an easy route to go. It was not enough simply to know and to accept that you were black—you had to look and act that way, too. You were going to be judged by how convincingly you could pull off the pose. One day when I was around nine years old, my mother drove Clarence and me over to Unisex Hair Creationz, a black barbershop in a working-class section of Plainfi eld. Back then we had a metallic blue, used Mercedes-Benz sedan, which from the outside seemed in good condition, though underneath the hood it was anything but, as the countless repair bills Pappy juggled would attest. While the three of us waited for the light to change colors, I became transfixed by the jittery figure of a long, thin black woman in a stained T-shirt and sweatpants, a greasy scarf wrapped around her head. She was holding an inconsolable baby in one hand and puffing on a long cigarette with the other, stalking the second-floor balcony of a beat-up old Victorian mansion that had been converted into apartments.\ I must have really been staring at her, because all of a sudden I noticed that she wasn’t aimlessly pacing back and forth anymore but pointing and yelling specifically at our car. “What the fuck are you staring at?” she howled. “You rich, white motherfuckers in your Murr-say-deez, go the fuck home! You think you can just come and watch us like you in a goddamn zoo?”\ She was making a scene. Passersby in the street were taking notice and looking at our car, too. That was a time when Benzes were the shit and you had to be careful where you parked because tough guys would pull off the little hood ornament and wear it from a chain around their necks—ready-made jewelry. I was terribly uncomfortable being the center of attention there in that backseat, mentally pleading for the light to turn green. I was also confused as hell. Who were these white people this woman kept referring to? Was she talking about . . . us—was she talking about me? Of course my mother was white, but I didn’t understand how she could think I was white, too. After all, I was on the way that very moment to have my hair cut at the only barbershop in the area that would cut hair like mine—curly, nappy hair. The kind that “didn’t move,” the kind of hair that disqualified me from getting cuts at the white barbershop two blocks from my house. But this woman was talking to me.\ “Just ignore her,” my mother said, and finally we drove away. But I couldn’t drive that woman’s angry face out of my head. She had somehow stripped me of myself, taken something from me. I felt I had to protect myself from ever feeling that kind of loss again.\ When I stepped into the barbershop that day and every second Saturday afterward, I was extra careful to pay attention to the other black boys sitting inside, some with their uncles, some with their fathers and brothers, some sitting all alone. These boys became like models to me. I studied their postures and their screwfaces, the unlaced purple and turquoise Filas on their feet, their mannerisms, the way they slapped hands in the street. These boys would never be singled out and dissed the way I had been. I decided I wanted whatever it was that protected them.\ Inside Unisex, it smelled deliciously of witch hazel and Barbasol, and there were three long rows of cushioned seats facing five swiveling barber’s chairs like bleachers in a gymnasium. There was an old, fake-wood-paneled color television suspended from the ceiling in the far back corner. If a bootlegged movie wasn’t playing on the VCR, the TV stayed stuck on one channel in particular the rest of the time, a channel I soon learned was called Black Entertainment Television. At the time in the morning when I usually came into the shop, the program Rap City would be showing. These barbershop Rap City sessions were not my first exposure to hip-hop music and culture, of course; I had been aware of it vaguely through the tapes my brother brought home and played in his bedroom. I don’t believe, though, that I had ever noticed BET before, and in the strange, homogeneously black setting of Unisex Hair Creationz and the city of Plainfield beyond it, the sight of this all-black cable station mesmerized and awed me. Watching BET felt cheap and even a little wrong on an intuitive level—my parents wouldn’t admire most of what was shown; Pappy called it minstrelsy—but the men and women in the videos didn’t just contend for my attention, they demanded it, and I obliged them. They were all so luridly sexual, so gaudily decked out, so physically confi dent with an oh-I-wish-a-nigga-would air of defiance, so defensively assertive, I couldn’t pry my eyes away.\ One morning, Ice-T’s “New Jack Hustler” video came on, and though I didn’t know the meaning behind the title—or even whether I liked what I was hearing—I knew for sure that the other boys in the shop didn’t seem to question any of it, and I sensed that I shouldn’t, either. All of them knew the words to the song and some rapped along to it convincingly. I paid attention to the slang they were using and decided I had better learn it myself. Terms like “nigga” and “bitch” were embedded in my thought process, and I was consciously aware for the first time that it wasn’t enough just to know the lexicon. There was also a certain way of moving and gesticulating that went with whatever was being said, a silent body language that everybody seemed to speak and understand, whether rapping or chatting, which I would need to get down, too. Over the weeks and months that followed, as I became more and more adept at mimicking and projecting blackness the BET way, and while it was all still fresh to me, what struck me most about this new behavior was how far it veered not just from that of my white classmates and friends at Holy Trinity, but also from that of my father and the two older black barbers in the barbershop—sharp men who looked out of place in Unisex and who held the door and brushed parts on the sides of their heads.\ One afternoon I came home from the barbershop sporting an aerodynamic new hair creation of my own. “What on earth did you let them do to you, son?” Pappy said as soon as he saw me. (Our house was not spacious; the front door opened directly into Pappy’s study, which he had converted from what ordinarily would have been a living room. To enter the house was literally to step into his scrutinizing gaze.)\ “Huh?” I said, touching my hand to my head. The top was so flat and cylindrical it resembled an unused No. 2 pencil eraser; the sides and the back were shaved all the way down, revealing a shaft of high-yellow scalp.\ “What, they didn’t listen when you told them what you wanted?”\ “No, they did,” I said. “This is what I wanted.”\ “You wanted that?”\ “Well, yeah, it’s what everyone is wearing, Babe; it’s what’s on BET and in all the magazines.” (We call my father Babe when speaking to him casually, kind of a tu to the vous of Pappy.)\ “And you want to look like everyone else, son? Is that what you want?” He was staring at me intently now.\ I stood there before him, studying the Air Flights on my feet. I didn’t have a response he would find remotely respectable. The thing is that I did want to look like everyone else—everyone else in the barbershop and on that TV screen. After all, even in the backseat of a big ol’ Murrsaydeez, the woman on the balcony would never mistake a brother with a flattop like this for being white.\ Annoyed or dismayed by my new coif as he was, though, Pappy allowed Clarence and me a generous amount of latitude when it came to our personal style, as long as we were giving him our best efforts in what he cared about most: the development of our minds. What this meant, giving him our best, was not that we were pressured to place first in our classes or even to get straight A’s on our schoolwork, although it would have been welcome if we did. We were expected to maintain decent grades, but it was deeper than that. Pappy, no longer working as a sociologist, now put his PhD and extensive store of personal knowledge and reading to use running a private academic and SAT preparation service from our home. From the second grade on, giving Pappy our best meant we needed to try hard in school, but much more important than that, we needed to study one-on-one with him in the evenings and on the weekends, on long vacations, and all throughout the summer break. If we could not do that, he was able to make our home the most uncomfortable inn to lodge in. When Clarence began blowing off work, he didn’t just get grounded, he came home to find his bedroom walls stripped bare, his Michael Jordan and Run-D.M.C. posters replaced with pastel sheets of algebra equations Pappy had printed out and tacked up.\ As for me, the first time Pappy called me into his study to explain my summer schedule, I was seven and my eyes betrayed me, welling with tears against my will. When he looked up from his notes and saw this, he got so offended that he stormed out of the room and I fell into my mother’s lap crying. I did not want to do the work he had planned for me. I wanted to play with my friends and have sleepover parties. I wanted to capture fireflies in ventilated Smucker’s jars and beat Super Mario Brothers on Clarence’s Nintendo. That was the truth. However, more than anything, I wanted not to disappoint my father. With my mother’s encouragement and some Kleenex, I followed Pappy into his bedroom and told him that I had just had something in my eye and that, in fact, I had not been crying. I was eager to start studying, I told him. He suspended his disbelief and led me back to his desk, where he proceeded to lay out an intensive program of regimented work in syllogistic and spatial reasoning, vocabulary-building, Miller analogies, arithmetic, and reading comprehension—his signature cocktail.\ If Pappy was a tyrant, he was a gentle and conflicted one, who did not relish the role. He yearned for a time when he would cease having to be one at all. What he hoped was that if he could somehow just make reading and studying appealing enough to his boys, eventually we wouldn’t need his prodding anymore and we’d simply do it on our own. To that end, he made sure not just to dangle punishment over our heads, Sword of Damocles–style, and leave it at that. He went out of his way to be fair. If we just did what he asked without too much complaint, he would do us some real solids in return, such as paying us generously for our time (“Study- ing is your job, and an honest day’s work deserves an honest day’s pay”), intervening on our behalf when our mother doled out chores (“Studying is their only job”), and tolerating a slew of hair, clothing, and dating choices that were in flagrant violation of his personal tastes.\ Despite these enticements, Clarence would always find it diffi- cult to take to long periods of study, and he went through fits of resistance routinely. Being the younger brother, I had the advantage of learning from his mistakes and avoiding most of his battles. I was what Pappy called a “dutiful son.” Most of the time this dutifulness of mine sufficed. We were rarely in open conflict with each other, and he was almost always patient and playfully encouraging with me.\ “Thomas Chatterton,” he’d say, addressing me by my middle name as I sped through his study on my way to the kitchen, oblivious to my surroundings. “Do you know you wear the name of a brilliant poet, son?” he’d call from the other room.\ “Yeah, of course, Babe,” I’d say, poking my head into the refrigerator, looking for something sweet.\ “And do you know they call him the Marvelous Boy, his poetry was so fine?” he’d say, still talking to me from the other room.\ “Uh-uh,” I’d say with my mouth full.\ “Well, they do. His poetry was so fine, in fact, and he was so young when he wrote it, that the adults couldn’t even believe the work was his own. They all accused him of copying someone else, someone much older.”\ “They did?”\ “They sure did. And do you know that he became so distraught by this, he became so discouraged, that he killed himself when he was only seventeen years old? He decided he couldn’t live with the dishonor.”\ “That’s horrible.”\ “Yes it is, son. Life is not fair. But now you’re going to bring honor to his name, aren’t you? It’s very important that you do that, son.”\ “But I don’t know how to, Babe,” I’d say, returning to the study with a bowl of ice cream or a glass of soda in my hand.\ ”Well, you don’t have to be a poet, son. You can be a great philosopher, for example—pull up a seat.”\ “A philosopher?” I’d say, and sit down.\ “Yes, in fact, you’re a philosopher already, aren’t you?”\ “I don’t think so,” I’d say, my cheeks flushing.\ “Well, yes you are, son. Think about it: Do you question the things around you? Do you reflect on their meaning? Are you interested in the truth?”\ “Yeah.”\ “Then you’re a philosopher, son,” he would tell me, and I would laugh, embarrassed because I didn’t feel at all like a philosopher, whatever that was I could only imagine. I felt ignorant, which is what I confessed to him. And he would tell me that ignorance is the beginning of knowledge and talk of men named Socrates and Confucius. He revered these two men perhaps above all other men, Socrates for his edict to know thyself and Confucius for his devotion to learning and personal excellence, he said. I would sit there at Pappy’s desk, exhausting whatever sugary collation I had brought with me from the kitchen, and listen to him talk. “Well, I’ve told you enough,” he’d eventually say. “Now, you tell me—how am I going to grow up and be smart like you?” We’d laugh and I’d try to come up with some reply. These questioning talks I had with Pappy were so frequent in my childhood that to this day the name Socrates remains mingled in my mind with the image of my balding and bearded father seated in his study. I cannot think of one without inadvertently conjuring the other.\ Sometimes, though, Pappy grew impatient waiting for the love of learning to take root in me. “I don’t understand,” he’d say in moments of frustration, “how you can keep walking past all these books and never stop to pick up a single one of them. My people told me not to read—don’t you know what I would have done to have all this? Don’t you ever get curious, son?” These were simple, honest questions that sometimes he put to me with a shake of the head and wry smile. Sometimes, though, he didn’t smile at all. In these latter moments, the look on his face was nothing like anger and something like pain—a sort of deep, serious pain I have only seen replicated in pictures of black faces of a certain age and demographic. It was a pain that I knew I couldn’t have caused but somehow must have mistakenly activated. I would stand there looking at him, frozen, like a deer suspended in halogen beams, and stammer some weak response.\ That particular afternoon after my visit to the barbershop, Pappy let drop the subject of my rectangular head of hair and handed me my work for the day. There was no long talk and no sadness in his face that afternoon. “Memory exercises and then vocabulary, both synonyms and antonyms,” he said. “Write them all out on flashcards and then come see me.”\ “OK, Babe,” I said, and went to my room carrying a pale green tachistoscope, a stack of SAT and GRE word lists, and a thick Merriam- Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, glad to have dodged a confrontation. After a morning spent at the barbershop, submerged in Black Entertainment Television, speaking and thinking in my florid second tongue—Ebonics—it was time now to return to the staid and familiar language of my father.

\ Publishers WeeklyIn Williams' debut, he offers a memoir that focuses on his upbringing, primarily credited to a father who instilled in him a value of education and mature study habits over sports and recreation. Williams recalls that he spent many summer days growing up pouring over flash cards or his seemingly never-ending stack of books, while his peers swam and played outside. What little free time he had he spent at a local park playing basketball and idolizing the older boys, one in particular who loved Hip-Hop and had gained the street cred that came from violence when defending one's honor. Williams credits Hip-Hop and its legends for his ever-growing curiosity of what it means to be black, and initially considered popular rappers to be historians of African American culture. As Williams enters adulthood and begins his first semester at Georgetown, he meets people of many different ethnicities and cultures and his opinions of the black identity begin to change . Williams' innate respect for knowledge and analysis emerges, and he discovers the value of the people around him and real experience over image. \ Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalFirst-time author Williams offers a revealing memoir on a par with James McBride's The Color of Water: A Black Man's Tribute to His White Mother (1996) and Bakari Kitwana's more scholarly The Hip Hop Generation: Young Blacks and the Crisis in African American Culture (2002). Losing My Cool is the story of a mixed-race young man's intellectual journey, in which he examines the impact of cultural forces on today's youth. Williams effectively conveys the convergences and dichotomies that his life comes to reflect: frontin' with his boyz vs. mandated study with his taciturn father. As the story unfolds and Williams takes to philosophical self-examination, this juxtaposition highlights the tenuous balance today's youth face in traversing the path between peer/cultural pressure and intellectual success, while examining the negative effect one's cultural identification can have both on the individual and the collective. VERDICT Recommended for YA readers, undergraduates, and readers in sociology or urban studies.—Jewell Anderson, Armstrong Atlantic State Univ. Lib, Savannah, GA\ \ \ Jabari AsimIt would be a shame if Williams's thoughtful comments about hip-hop, which deserve and undoubtedly will receive articulate response, detract attention from other equally engaging portions of Losing My Cool. For example, his portrait of his dad, an intensely private man, contains some of the most compelling writing about black fathers in recent literature on the subject. There is much to admire in Losing My Cool, and more to anticipate from Williams.\ —The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Tara McKelveyFanwood, N.J., does not have a literary pedigree, or even a downtown bookstore, and yet it has produced a very talented writer.\ —The New York Times\ \