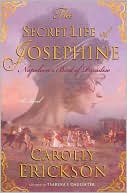

Losing Nelson

Losing Nelson is a novel of obsession, the story of Charles Cleasby, a man unable to see himself separately from the hero—Lord Horatio Nelson—he mistakenly idolizes. He is, in fact, a Nelson biographer run amok. He is convinced that Nelson, Britain's greatest admiral, who lost his own life defeating Napoleon in the Battle of Trafalgar, is the perfect hero. However, in his research he has come upon an incident of horrifying brutality in Nelson's military career that simply stumps all attempts...

Search in google:

"Stunningly original. . . . Pulpy and juicy, full of wisdom and horror." —Los Angeles Times Book ReviewPublishers WeeklyUnsworth (Sacred Hunger; Morality Play) delivers another memorable tour de force in this tense portrait of a London man obsessed with Britain's greatest naval hero, Lord Nelson. Charles Cleasby lives by the "Horatio calendar," reenacting Nelson's battles with model shops on a glass table in his basement. In his mind they are joined: Nelson is a radiant angel, a hero of unstained virtue, and he is Nelson's other, shadow side: "I was his heir, I had inherited his being." For years Cleasby has been writing a book extolling Nelson's heroism, but has become blocked over a controversial incident in June 1799, when Nelson apparently tricked two fortresses of Neapolitan rebels into surrendering, under promise of a safe conduct, then turned them over to their murderous Bourbon king and queen for hanging. Unsworth's control of his material, and his artistic ingenuity, his narrative skill in what is essentially a highly literate suspense novel, are supreme here. By compressing the milestones of one man's lifetime into the calendar of another man's year, he creates a shuffled chronology of historical events that parallels his narrator's wavering state of mind. Paragraph by paragraph, Cleasby's sense of self shifts and dissolves; in one paragraph he describes the view of Nelson's ship entering Naples harbor, in the next "we" are standing at its prow, and in the next it's "I" onto whose arm Lady Hamilton is swooning. Cleasby's erotic stirrings for Emma Hamilton and his misadventures with London's Nelson Club are the stuff of high comedy, and it's hard to say exactly why this novel seems so unsettling and suspenseful. Unsworth holds open a door to normalcy in Cleasby's growing attraction to Miss Lily--hired to transcribe his manuscript to a word processor--whose down-to-earth and very contemporary responses put Nelson on a more human scale. The book's surprise ending, held back to the final page, seems therefore all the more cruelly ironic--and probably the nastiest twist of any in recent fiction. BOMC selection. (Oct.) Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.

\ \ \ \ Excerpt\ \ \ I had a bad fright that morning. I wouldn't have left the house at all on such a special day if the man at Seldon's hadn't phoned to say they had a piece I might be interested in. It was an oval plate, bone china, frilled at the edges, slightly curved at the sides, pale cream in colour, with a central medallion enclosing his profile in dark blue. There was an inscription of the same colour in slightly worn cursive, running round the upper half of the medallion: Hero of the Nile. They had used the De Vaere profile made for Wedgwood in the summer of 1798. Nothing very remarkable about it. But of course I agreed to buy it. It bore his image. It was seldom indeed I could resist that.\ I was on my way back home with it, back to Belsize Park. It was a raw day and the sky was darkly overcast. Nevertheless, I decided to walk as far as Knightsbridge for the sake of the exercise. I had time to spare—or so I thought. As I was crossing Pont Street it started to rain, not very heavily. The platform in the Underground was crowded and became steadily more so while I waited. There was a silence among the people there, silence of waiting—they were resigned. I began to feel the first twinges of panic. Then an Asian voice on the loudspeaker: a delay on the line due to security checks at Gloucester Road station.\ It was thirteen minutes to twelve. Imagine my feelings. This was February the fourteenth; it was the two hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, Horatio's first great disobedience, the day he became an angel. On this day, at 12:50 p.m.—just over an hour's time—his ship, theCaptain, went into close action. And here was I among this mute herd, sweating despite the cold, a good two miles from my table and my models. The ships were not even set out.\ It mattered so much to get the time right, therein lay the whole meaning—how else could I keep my life parallel with his? Before my father died—he died last April—I fought out this battle wherever I could: on my bed, on the floor, one freezing day in the shed behind the house. We never missed, year after year we broke the line at ten minutes to one. Now I had the basement all to myself. The thought that I might fail the appointment now was unendurable, it made me feel sick.\ There was no time to be lost. I struggled back to the surface along with numbers of others who had made the same decision. I was feeling distinctly unwell by now; my breath came with difficulty and there was the usual suffusion of blood at the temples, obscuring my vision, making me feel hemmed-in. It was still raining and there were no free taxis anywhere near the tube, nor outside Harrods. I had to walk some way towards Hyde Park Corner before I found one, and even then I was lucky; the previous fare was alighting as I came up. I gave the address and sat back and concentrated on keeping my face composed and my breathing inaudible. Closing the eyes has always helped me to cope with anxiety, but now I waited two minutes by my watch before allowing myself the luxury. Timing is the key to control, and control is the key to concealment. The driver, if he glanced in his mirror, would think it strange if his passenger were dozing too soon.\ My father was a master of concealment; he kept it up so well that nobody knew just when he died, nobody registered the precise moment. We made it with twelve minutes to spare. I was still gasping a little as I went down to the basement. I did not allow myself to be sidetracked by considerations of where among the shelves and cabinets to put my new acquisition; such a decision would involve extensive rearrangement, it could easily have taken the whole afternoon, in these last months I had got steadily slower. I simply left the plate, still in its damp wrapping, on the floor and went straight through to my operations room and began setting out the ships, the Spanish first in their two loose groups, 9 in the van, 18 in the rear, these last headed by de Córdoba in his great flagship, the Santissima Trinidad, 4 decks, 136 guns, the most powerful wooden warship ever built. One of the first models I made; I was fourteen, home from school for the summer holidays. Odourless now, the ship in my hands, but still seeming to bear the spiritous, heady scents of its making—glue, paint, freshly cut shavings. The shed had a smell too, dust and hot creosote and the rank weeds that grew against the boards outside. Smells are more intense for solitude and remembered more intensely, as every lonely person knows. Sounds too. But I wasn't lonely, I had him.\ Now for the English fleet, under Admiral Sir John Jervis in the Victory, Horatio's death-ship at Trafalgar eight years later—eight years, eight months, and one week. In contrast to the disorderly Spanish, our ships are sailing in impeccable close order, fifteen warships in perfect line-ahead formation, approaching from the south at right angles, making for the fatal gap in the enemy fleet, two feet wide on my table, roughly seven miles in actual fact.\ The sight of them now, disposed for battle, gunports open and cannon run out, quite restored my calm. In full press of sail, with their flags and pennants and painted hulls, their figureheads picked out in gold and vermillion, they made a fine show. How much care and devotion I lavished on those models, those sloops and frigates and ships of the line, what pride I took in them. Before my father died I had to keep them in cardboard boxes in my bedroom, together with all the other Nelson memorabilia I had collected over the years. My room was full of boxes, you couldn't get the door more than half open, you had to edge your way in. Now my ships had for their manoeuvres the whole surface of the billiard table that had always been a feature of the basement. My brother Monty and I used to play on it sometimes, before he left. I had covered it with dark blue baize and had a sheet of glass fitted exactly over it. In the light of the lamp overhead—no daylight ever entered that room—the surface glinted like dark water and reflected the colours of the ships.\ Eight minutes to go. Since first light these stately, deadly vessels have been slowly drawing closer together, approaching in a fashion apparently leisurely the thunder and carnage of a close encounter. Incongruous, and to me entirely fascinating, this dreamlike slowness. Consider the ferocious fire power of those ships, their capacity for destruction, more devastating than anything known before, on sea or land. Jervis is taking well over a thousand cannon into action with him. Now they are 25 miles west of the Portuguese headland of St. Vincent, 150 miles northwest of Cadiz, for which port the Spanish are running with a fair wind.\ They would avoid the engagement if they could, but they cannot be allowed to, they must be intercepted. A heavy weight of responsibility lies on Jervis's shoulders today. The French Revolutionary War has reached a crucial phase. The Dutch fleet has joined with the French at Brest. One attempt to invade Ireland has already been made. Admiral Lord Bridport's Channel Fleet has been driven back to England by bad weather and forced to abandon the blockade of Brest. Only this same bad weather has so far prevented an enemy break-out and an unopposed Irish landing. If the Spanish are allowed to join them, the odds will become impossible. Not only have the English been forced to quit the Mediterranean—a vital sphere of influence—but the whole of continental Europe is now dominated by the armies of France. Drained by the subsidies she has been obliged to pay to keep her allies in the field, her trade routes curtailed, her merchantmen harassed by privateers, England is on the verge of bankruptcy. Ireland is simmering with rebellion. There are rumours of mutiny in the ships of the Royal Navy. It is indeed true, what Admiral Jervis is heard to remark as the weather brightens: "A victory is very essential to England at this moment." Words that are remembered, recorded, famous words. But this brightening weather has revealed an awesome discrepancy in the strength of the opposing fleets. Jervis has fifteen sail of the line. Six of them are three-deckers, but only the Victory and the Britannia have as many as a hundred guns. All the rest, including Horatio's, are two-deck ships with seventy-four guns, the standard warship of the Royal Navy at that time. In addition Jervis has four frigates, faster than the line ships, essential for scouting and intelligence. I set them out now, on a diagonal, to windward of the English line. This is the force with which Jervis is proposing to engage the Spanish Grand Fleet, twenty-seven ships of the line, ten frigates, and a brig. Six of the Spanish three-deckers are carrying 112 guns, and there is the mighty Santissima Trinidad with 136. Altogether they have twice the fire power of the English. But there are compensating factors. The Spanish have put to sea in haste, they are undermanned, their officers are inexperienced.\ Everything is in place. It is fourteen minutes to one. One hour and four minutes previously, while I was panicking at Knightsbridge, Jervis had given a bold and unconventional signal. On this occasion he cannot follow the rigid procedures laid down by the Admiralty in London for the conduct of sea battles, procedures that have not changed in a hundred years: You lay alongside, preserve strict in-line formation, and pound away in a duel of broadsides until the enemy is crippled or surrenders or runs. Jervis cannot do this because his force is too inferior; he would be overwhelmed. So he has given the order to put on press of sail and break through the gap in the enemy formation. It is the only tactic possible. Once through, the English fleet can attack to windward, concentrating its fire on the eighteen ships of the rear, disabling them before the van can make the turn into the wind and come to their aid.\ A perfect day for sea fighting—calm, with a light breeze, no rolling to disturb the calculation of the gunners. I check that the English ships are in correct order of sail as they pass through the enemy, Troubridge leading the van in the Culloden, Collingwood bringing up the rear in the Excellent. Third from the rear is Horatio in the Captain, flying the Broad Pennant; he is a commodore now—since the previous March. So they pass through. The Spanish spine is severed. But now Jervis blunders. He cannot altogether break from his conditioning, free himself from the rigid code of line-ahead formation. He hoists his signal: once through to the west of the Spanish, the fleet is to tack in succession and bear down on them. In succession. No sir, wrong. It should have been simultaneously. For fifteen ships to make the turn, one after the other, each waiting till the one ahead has completed the manouevre, and then to reform in line—this will take too long, the advantage will be lost.\ But of course they obey, they are bred to obedience. Here they are now, in a wide inverted V on the ocean as they begin to execute the manouevre, in perfect formation still, the Culloden still leading. But the Spanish have the wind. De Córdoba has understood, he alters course northwards, he means to bear over the wind and unite his fleet. Then he can fight or run as he chooses, and he will have time to do it; only the first six English ships have so far completed the turn and they have not yet come up with the Spanish, they are still out of range. One man sees this, and that man is Horatio Nelson. It is now 12:50 p.m. Without a second's hesitation, disregarding his commander's signal, he veers the Captain away from the wind, he breaks the line. The audacity of it, the impetuous logic! To recognize absolute necessity and act on that instant of recognition. Now again, in this silent room, as I send the Captain into the attack and her colours glint on the dark surface, I feel a constriction in the throat and my heart beats faster at the dash and defiance of it. The move has brought us, at a stroke, across the bows of at least seven Spanish ships, among them the huge Santissima Trinidad, the San Josef, the Salvador del Mundo, and the San Nicolas, these four alone possessing 440 guns against Horatio's 74.\ At the moment that he swung away from the wind and broke the line, risking the outcome of the battle and his whole career on this one throw, at that moment, in his thirty-ninth year, Horatio became an angel. He entered a different sphere. I will say what I think angels are. They can be dark or bright, but they all have the gift of spontaneity, of creating themselves anew. This is a pure form of energy, and Horatio was winged with it. All the same, angels are not complete, they need their counterparts, the dark needs the bright, the hidden needs the open, and vice versa. Sometimes they meet and recognize each other. Sometimes, as with Horatio and me, the pairing occurs over spaces of time or distance. He became a bright angel on February 14, 1797, during the Battle of Cape St. Vincent. I became his dark twin on September 9, 1997, when I too broke the line. I had no presentiment of this on that February afternoon, as I moved my model ships about on their glass ocean. Since my father's death I had been experiencing bouts of gloom—not sorrow—and at times a sort of excited restlessness that made it difficult for me to keep still. And I had run into a difficult patch in the book I was writing, The Making of a Hero. I had got bogged down in the events of June 1799 in Naples and Horatio's part in them. This book had been going on for more than five years, ever since December 1991. I started it on Boxing Day, the anniversary of his mother's death. The Naples business was worrying me; I could not leap over it. Progress was slow; lately, in fact, there hadn't been any. I kept retreating, rewriting pieces of his earlier life. It was for this reason that I began to feel slightly uneasy now, as I went on with the battle. Because at this point I had to bring Troubridge into the action, and at the time I did not much care to dwell on Troubridge, Horatio's brother officer and friend, closely associated with him in this battle but also in the treatment, two years later, of the Jacobin rebels in Naples—the business that was holding me up with my book.\ Certainly there is no doubt of his fighting spirit. Horatio is not left long to fight alone. He is joined by Troubridge in the Culloden, the leading English ship, which has now completed the turn ordered by Jervis and come within range. For nearly an hour these two exchange broadsides with the Dons, superior discipline and gunnery making up for inferiority of armament. Now here is the gallant Blenheim coming up to give them a respite, passing between them and the enemy, pouring fire as she goes. The Culloden is crippled, she falls astern. Collingwood ranges up in the Excellent, last ship of the line. He passes within ten feet of the San Nicolas, eighty guns, and blasts her in masterly fashion with two broadsides in succession.\ Ten feet. The length of this table. That would be about it. Almost jumping distance. These towering ships, fighting so close, hardly more than the length of a man between them, launching their thunderous fire, shuddering from stem to stern with the repeated recoi

\ From Barnes & NobleThe Full Nelson \ Barry Unsworth's Losing Nelson is a magnificent tale of celebrity, obsession, and what it's like to be woefully out of touch with the world around you.\ It's also about the career of Lord Horatio Nelson, the celebrated 19th-century British naval hero who defeated Napoleon and lost his own life in the historic Battle of Trafalgar.\ Charles Cleasby is a reclusive contemporary Londoner who lives alone—except for the artifacts and information he collects about his hero, Nelson. In fact, just about all Cleasby does is Nelson-related: He re-enacts Nelson's battles on a giant blue-glass table in his basement; he studies all available materials ever published on his hero; he lectures occasionally on Nelson at a local historical/literary club. Cut off and about as emotionally unevolved as a contemporary middle-class Westerner can be—he might remind some readers of an older, British version of the title character in Anne Tyler's The Accidental Tourist—Cleasby is content to spend his day chasing Nelson. The only outside influence he has, in fact, is a secretary named Miss Lily, who comes weekly to help him organize the mountains of material he collects. Miss Lily, of course, is a much more contemporary sort and a real "girl": she's intent on making Cleasby consider the personal aspects of Nelson's life—Nelson was married, and his flagrant affair with Emma Hamilton flew in the face of 19th-century (and Miss Lily's current) values. She also tries to bring Cleasby into the present by cajoling him into an outing with her and her son. For a while, it looks like the novel will center on an Accidental Tourist-like romance between two opposites. Will Charles Cleasby's remarkable reserve (even for a Brit) be pierced by the loving ministrations of an equally lonely secretary? Will this neglected and neglectful guy—who reveals to us a bit about his troubled childhood—learn to live and love again?\ This is one of the questions raised by Unsworth's captivating book, but it is only one. The author is long-used to pursuing multiple themes (see his Morality Play and Sacred Hunger, which, in 1992, shared the Booker McConnell Prize with Michael Ondaatje's The English Patient)and here, as usual, Unsworth has constructed a multidimensional novel. Losing Nelson's juxtaposition of dreamlike sequences and wry, contemporary observation rivals Ian McEwan's Amsterdam (which, incidentally, won the 1998 Booker Prize.) It's as if Unsworth understands precisely the reader's capacity for historical detail—and knows just when to leaven his rather sad story with biting satire. (One scene in which Cleasby discovers that a fellow Nelsonophile is also a fan of David Bowie is a priceless piece of social commentary.)\ But Unsworth also knows his character well. Make no mistake: Charles Cleasby is no victim; he does not feel sorry for himself; he is not looking to be "saved." In fact, he's so immersed in Nelsoniana that he has become, in his own mind, indistinguishable from his idol. If Nelson is noble, then he is, too—which is why it is so hard for him to face any proof of Nelson's humanity. In one scene late in the novel, Cleasby has been compelled to go to Naples to try to deconstruct the one horrific, brutal incident in Nelson's history that even he cannot explain, much less glorify. In meeting a local historian, Cleasby launches into his usual speech about Nelsonian glory only to be met with stony disapproval; it had never occurred to Cleasby that the Italians—who were slaughtered by Nelson's men—might see the admiral a little differently. "You have come for the wrong hero," the Neapolitan tells him. "Caracciolo is the hero here. Heroes are always local." Cleasby's reaction is not, of course, to question his idol or his own idolatry but to lament his colleague's small-mindedness. "It was clear that heroes meant little to him," Cleasby thinks. "This was a person without ideals." Cleasby, of course, has more than his share of ideals, but when it becomes apparent that neither he nor Nelson is everything he imagines, he begins a fatal descent into madness.\ Clearly, there's a lot to chew on here—both factual and fictional—but for all its historical detail, Losing Nelson never feels like a history lesson. Instead, it is a universal, contemporary tale that examines issues very relevant to our time: Why do we exalt some people as heroes? Should a hero be held to the same—or higher—moral and emotional standards as the rest of us? How much does the hoi polloi need to know or to care about a public figure's private behavior? Reading Unsworth may not explain our fascination with Bill Clinton, George Bush, or Brad Pitt, for that matter, but it will surely make us question that fascination. In other words, Charles Cleasby may be stuck in the 19th century, but Unsworth is very much a writer of the moment.\ —Sara Nelson\ Sara Nelson, formerly executive editor of The Book Report and book columnist for Glamour, is now editor-at-large of SELF magazine. She also contributes to Newsday, the Chicago Tribune, and Salon.\ \ About the Author\ Barry Unsworth won the Booker Prize in 1992 for Sacred Hunger, his next novel, Morality Play, was a Booker nominee and a bestseller in both the United States and Great Britain. He lives in Umbria with his wife and recently held the position of Visiting fellow at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop.\ \ \ \ \ \ Publishers Weekly\ - Publisher's Weekly\ Unsworth (Sacred Hunger; Morality Play) delivers another memorable tour de force in this tense portrait of a London man obsessed with Britain's greatest naval hero, Lord Nelson. Charles Cleasby lives by the "Horatio calendar," reenacting Nelson's battles with model shops on a glass table in his basement. In his mind they are joined: Nelson is a radiant angel, a hero of unstained virtue, and he is Nelson's other, shadow side: "I was his heir, I had inherited his being." For years Cleasby has been writing a book extolling Nelson's heroism, but has become blocked over a controversial incident in June 1799, when Nelson apparently tricked two fortresses of Neapolitan rebels into surrendering, under promise of a safe conduct, then turned them over to their murderous Bourbon king and queen for hanging. Unsworth's control of his material, and his artistic ingenuity, his narrative skill in what is essentially a highly literate suspense novel, are supreme here. By compressing the milestones of one man's lifetime into the calendar of another man's year, he creates a shuffled chronology of historical events that parallels his narrator's wavering state of mind. Paragraph by paragraph, Cleasby's sense of self shifts and dissolves; in one paragraph he describes the view of Nelson's ship entering Naples harbor, in the next "we" are standing at its prow, and in the next it's "I" onto whose arm Lady Hamilton is swooning. Cleasby's erotic stirrings for Emma Hamilton and his misadventures with London's Nelson Club are the stuff of high comedy, and it's hard to say exactly why this novel seems so unsettling and suspenseful. Unsworth holds open a door to normalcy in Cleasby's growing attraction to Miss Lily--hired to transcribe his manuscript to a word processor--whose down-to-earth and very contemporary responses put Nelson on a more human scale. The book's surprise ending, held back to the final page, seems therefore all the more cruelly ironic--and probably the nastiest twist of any in recent fiction. BOMC selection. (Oct.) Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ Library JournalCharles Cleasby is a reclusive scholar so obsessed with the British naval hero Horatio Nelson that he celebrates key events in the admiral's life as if they were religious holidays. Hopelessly stalled on his definitive biography of the decisive leader, Cleasby hires an assistant from a secretarial agency. This opinionated young woman offers a running criticism of Nelson as she takes dictation. Did he ever think about the young men he ordered to their deaths, did he share prize money with his crew, was it honorable and heroic to begin an adulterous affair with Emma Hamilton? Her skepticism so infects Cleasby that he fixates on one decidedly unheroic moment in Nelson's career, his murderous double-crossing of hundreds of Neapolitan rebels who na vely surrendered to him. Though filled with factual detail about Nelson and his time, this cunningly bizarre novel is more a psychological thriller than a work of historical fiction. Booker Prize winner Unsworth is in complete control of his material, effortlessly sustaining an almost unbearable level of tension that is suddenly resolved in an unusually effective surprise ending. An exceptional performance; highly recommended.--Edward B. St. John, Loyola Law Sch., Los Angeles Copyright 1999 Cahners Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsIn a novel of singular complexity, Unsworth (Sugar and Rum, p. 481, etc.) sheds remarkable light on the nature of obsession, as a daft but supremely knowledgeable biographer of British naval hero Lord Horatio Nelson fights desperately against the evidence to rescue his subject from a distinctly unheroic deed. Day by day, history is reenacted in the London basement of Charles Cleasby, as he celebrates all of Nelson's victories at sea on a glass-topped table filled with ships handcrafted to scale. Living alone and well-off after his father's death, Charles has no impediment to the lifelong pursuit of this celebration and its accompanying biography, save one: He can't explain to his satisfaction what happened in Naples on June 26, 1799, when his bright angel Horatio apparently defied a treaty and, using base deceit, sent hundreds of antimonarchist opponents, the flower of Naples society, to their deaths at the hands of their vengeful former ruler. Complicating matters for Charles is the fact that the secretary he's engaged to help with his book, a no-nonsense, kindhearted woman he nicknames Miss Lily and for whom he begins to have some feeling, is highly critical of Horatio's vanity and blood lust. After months of work on the manuscript—and an outing together with her teenage son to see Horatio's flagship— Miss Lily reluctantly leaves for the summer on another job. The seeds of doubt she's sown in Charles's mind so tarnish his view of the man he's come to consider his shining twin, his other, that he feels compelled to go to Naples in search of evidence that will redeem them both. What he finds instead unites him with his hero in a manner that brooks no return. Psychodramaand historical suspense align to extraordinary effect here, entwining the two in a denouement both stunning and unspeakably sad. (Book-of-the-Month Club)\ \