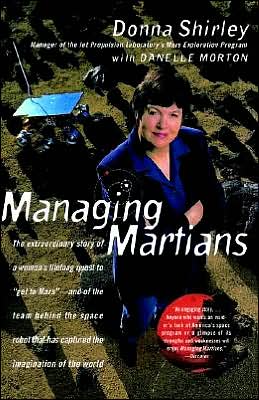

Managing Martians

Donna Shirley's 35-year career as an aerospace engineer reached a jubilant pinnacle in July 1997 when Sojourner--the solar-powered, self-guided, microwave-oven-sized rover--was seen exploring the Martian landscape in Pathfinder's spectacular images from the surface of the red planet. The event marked a milestone in space, but for Donna Shirley, the leader of the mostly male team that designed and built Sojourner--and the first woman ever to manage a NASA program--it marked a triumph of...

Search in google:

Donna Shirley's 35-year career as an aerospace engineer reached a jubilant pinnacle in July 1997 when Sojourner—the solar-powered, self-guided, microwave-oven-sized rover—was seen exploring the Martian landscape in Pathfinder's spectacular images from the surface of the red planet. The event marked a milestone in space, but for Donna Shirley, the leader of the mostly male team that designed and built Sojourner—and the first woman ever to manage a NASA program—it marked a triumph of another kind.Managing Martians is Shirley's captivating memoir of a life and career spent reaching for the stars. From her seemingly outlandish aspiration at age ten to build aircraft, to abandoning high school Home Ec in favor of mechanical drawing, and, at sixteen, becoming a licensed pilot, Shirley defied expectations from the beginning. In a vivid narrative, rich with anecdotes and thrilling turning points, Shirley recounts the intense battles she waged to defend her vision and the ingenuity and resourcefulness of her committed team. Her moment-by-cliffhanging-moment account of Pathfinder's landing and Sojourner's first tentative foray across the sands of Mars brilliantly captures the fulfillment of a lifelong dream as it heralds a brave new era of space exploration. Publishers Weekly What do you do if you are a tomboy daughter of the two most prominent families of Wynnewood, Okla., a small town in the middle of the U.S. in the middle of the 20th century? If you're Shirley, you set a course for Mars. Along the way, even if you smell of airplane glue instead of White Shoulders, you enter horse shows; and even if you are struggling academically and socially as the only female engineering student in your class at the University of Oklahoma, you enter and win the Miss Wynnewood contest. In this autobiography as unself-conscious as Shirley apparently is herself, the first woman to manage a NASA space flight program invites readers to follow her adventures, beginning with an awkward childhood, through four decades of failure and success, culminating not in an end but in a new beginning. "Where do you go after you've been to Mars?" her epilogue asks. "Where do you go after you've reached the pinnacle of what you imagined for yourself?" The answer is to pursue a new passion, to discover once again what you want to do when you grow up. "The question is only: Which passion do I want to pursue?" she declares. "Stay tuned." This book will certainly appeal to unconventional women, but it also belongs on the reading list of teenage nerds and adult former nerds, of anyone who has ever misstepped, of anyone who has ever been uncertain, of anyone of any age who still dreams of reaching beyond the horizon.

Prologue: Six Wheels on Soil\ Before dawn on July 4, 1997, I woke with my mind over a hundred million miles away. My waking thoughts were all of Pathfinder, the United States' first attempt to land on Mars in twenty years, as it hurtled through the silence of space just hours away from its encounter with the red planet. The 100-foot-high Delta 2 rocket that had boosted the spacecraft from Cape Canaveral, Florida, seven months earlier was finally about to deliver something very precious to me, and I can't say I wasn't anxious.\ Cabled down firmly inside this streaking bullet was Sojourner Truth, the world's first robotic planetary rover. I headed the team that had designed and built this revolutionary six-wheeled scientific laboratory, a 25-pound robot about the size of a microwave oven that could do what humans could only dream of: explore the surface of Mars. I'd spent nearly ten years of my life preparing the two of us for this moment.\ I could picture her cradled in the heart of the lander like the tiniest Russian nesting doll. She crouched with her belly to the floor inside a lander that was packed in a cushion of deflated airbags. Once off the lander, she would motor over the surface of Mars taking pictures and poking at the rocks like a tourist. She was a sturdy little gal. We'd whirled her in a centrifuge at a force 66 times that of gravity, twice as much pressure as we expected her to endure in flight, and she'd come out perfectly. If Pathfinder landed the way it was supposed to, I was sure she'd be fine.\ I knew the Pathfinder's innovative landing mechanism almost as intimately as I knew the rover. Retro-rockets would slow the craft to a stop just before it smacked into the Martian surface. Moments before it hit the ground, huge airbags would pop. If everything worked--if all the radios communicated, the signals and sequences were sent and received, every one of the explosive bolts fired promptly and the airbags popped firm exactly on cue--it would plump up and bounce across the ground like a giant superball until it came to a rest. It was an inspired and thoroughly tested design, but one that had never before been used to land on a planet.\ Surely this scheme had a better chance of keeping the Sojourner intact than anything previously devised. The teams that designed the lander and the rover had spent hours concocting every imaginable disaster scenario and building in ways to overcome those. We were combating long odds, if history was to be believed. Throughout thirty-seven years of exploration, Earthlings hadn't been terribly successful landing on Mars.\ Two Russian Phobos spacecraft were lost on their way to Mars in 1988. While the United States' two Viking missions landed safely in 1976, our Mars Observer failed to reach orbit in 1993. The Russians' Mars 6 and 7 got to Mars in 1971, but couldn't deliver their landing craft. Mars 6 crashed into the surface and Mars 7 missed the planet completely. As recently as November 1996, the Russian Mars 96 mission plunged ignominiously into the Pacific, never getting anywhere near its target. What if something like that happened to my rover? The data assured me that Pathfinder was approaching Mars just fine, but almost anything could happen during the punishing six-minute descent to the surface. Crash and burn was a definite possibility, I knew. Crash and burn.\ Of course she wasn't really my rover. I had headed the team of thirty talented engineers and technicians that had spent four years designing and building the rover. A separate 300-member team, led by project manager Tony Spear, had spent the same amount of time building the Pathfinder lander. All of us could rightfully think of this mission as our own. No matter what any of us were doing at that moment on Earth, we could picture Pathfinder and Sojourner about to begin their descent and we knew our hopes could be dashed against the forbidding landscape.\ I hadn't slept at all well that night. I've always been a fitful sleeper anyway, tossing and turning in the wee hours anticipating the day to come as my mind races with ideas and plans. In the early morning hours before Pathfinder entered the Martian atmosphere, dreams yanked me just to the edge of consciousness time and again. These weren't the idyllic dreams of me flying solo over the surface of Mars, such as I'd had since I was a small child in Oklahoma. The dream that eventually convinced me I might as well get out of bed was more of a farce.\ In this dream, I saw the Pathfinder team standing around a field when suddenly our spacecraft fell from the sky before us. It had landed on Earth! We watched it bound to a stop but the airbags didn't deflate. My teammates seemed merely befuddled by this disaster. I hopped around eagerly, wondering how they could be so detached. I wanted to open it up, see how Sojourner had survived the descent. Everyone else said we had to let the lander open by itself. I guess I should see this dream as an encouraging omen, I decided as I got out of bed. If Sojourner could endure the descent through the Earth's dense atmosphere--even in my dreams--then the wispy carbon dioxide atmosphere of Mars would feel as gentle as a tropical breeze.\ I found no comfort in my morning ritual, no solace from my habitual cup of tea. I barely tasted my orange as I methodically swallowed it. Sitting at home was just making me restless. I felt like a child the night before Christmas anticipating a desperately-wished-for present. I put on my favorite suit--Mars red--and decided it was best not to wake my daughter, Laura, who was home from college for the summer. She planned to catch up with me around 10 a.m.,the moment the Pathfinder was scheduled to enter the Martian atmosphere. She could use the sleep for the eventful day ahead, I thought. I drove the six miles from my house in La Canada to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in California, arriving at 6:30 a.m., an hour before I was supposed to report for work.\ Though I'd driven the two blocks of Oak Grove Drive nearly every day for the thirty years I'd worked at JPL, I'd never seen it as packed with journalists as it was that day. Local, national, and international television trucks lined the street. Von Karman Auditorium, near the entrance to the JPL campus, bustled with print and radio reporters already hard at work on this story. Photographers snapped pictures of the full-scale models of the Pathfinder we'd displayed on the JPL mall and in the auditorium. Video crews jockeyed for position around the models and on the risers at the back of the auditorium. Competition for a good spot was so heated that JPL had taped off separate areas for each crew to prevent squabbles. I knew the Fourth of July was a slow news day, but I'd never expected the interest to be as high as this. Something about Pathfinder and Sojourner had really captured the public's imagination.\ The generation that had grown up watching Star Trek and Star Wars really hadn't seen a planetary landing in its lifetime. For this generation, the Pathfinder mission was akin to Neil Armstrong's moon landing on July 20, 1969. We knew we already had a built-in international audience of the millions of people who had tracked the mission's progress on the Internet Web site we'd constructed for Pathfinder before it took off on December 4, 1996. Popular culture fostered an interest in space, but the real world rarely delivered the goods. Today--on Independence Day no less--the real world was delivering.

\ Publishers Weekly - Publisher's Weekly\ What do you do if you are a tomboy daughter of the two most prominent families of Wynnewood, Okla., a small town in the middle of the U.S. in the middle of the 20th century? If you're Shirley, you set a course for Mars. Along the way, even if you smell of airplane glue instead of White Shoulders, you enter horse shows; and even if you are struggling academically and socially as the only female engineering student in your class at the University of Oklahoma, you enter and win the Miss Wynnewood contest. In this autobiography as unself-conscious as Shirley apparently is herself, the first woman to manage a NASA space flight program invites readers to follow her adventures, beginning with an awkward childhood, through four decades of failure and success, culminating not in an end but in a new beginning. "Where do you go after you've been to Mars?" her epilogue asks. "Where do you go after you've reached the pinnacle of what you imagined for yourself?" The answer is to pursue a new passion, to discover once again what you want to do when you grow up. "The question is only: Which passion do I want to pursue?" she declares. "Stay tuned." This book will certainly appeal to unconventional women, but it also belongs on the reading list of teenage nerds and adult former nerds, of anyone who has ever misstepped, of anyone who has ever been uncertain, of anyone of any age who still dreams of reaching beyond the horizon.\ \ \ \ \ Glamour Magazine"If humans ever visit Mars -- and it could happen as early as 2010 -- it may be Donna Shirley's legacy that makes their awesome landing possible."\ \ \ Mirabella"Describing [Sojourner's] wonders, Shirley is part proud parent, part car salesman, and part stand-up comic."\ \ \ \ \ Los Angeles Times"Her phone number spells MARS, her car is a Staurn, and her home is the closest you can get to a cabin in the sky. Donna Shirley isn't your ordinary Earthbound mortal. In fact, for 30 years she has spent 8 to 18 hours per day planning how to get out of this world and onto other planets."\ \ \ \ \ Buzz"One of L.A.'s '100 coolest People,' Shirley is the colorful ring-leader of the team that created Mars's first sport-utility vehicle."\ \ \ \ \ MS"Shirley's ability to boil down complex scientific concepts into tangible sound bits has helped her pick up where Carl Sagan left off -- making the field more accessible and interesting to a populace intimidated by science."\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsTo paraphrase the old soap opera: Can a rich girl from a small Oklahoma town find success and happiness married to her job as first woman manager of a NASA space program? The answer is a resounding yes as recounted in this spirited autobiography by Donna Shirley with People correspondent Morton. Shirley led the design team that built the microwave-size, six-legged robot that explored Mars in the Pathfinder project launched July 4, 1997. Sojourner traversed 100 meters of Martian surface, returning 550 images and 15 chemical analyses of soil and rocks, far exceeding expectations. The story opens with the successful launch, not without a few hairy moments, and then flashes back to the young Shirley, the tomboy offspring of the premier families of Wynnewood, Okla. (population 2,000-plus). Father was the town physician, mother the clergyman's athletic-minded daughter, allowed to train dogs and lead a Girl Scout troop but otherwise required to conduct herself as society matron. Inevitably, this led to maternal-filial friction as some of ma's frustration worked itself out in perfectionist demands that Donna excel at sports and social attractiveness. All this entered the equation that shaped Donna's ambitions—to become an aeronautical engineer. She took flying lessons at 16 and got her degree in aerospace/mechanical engineering. Soon after, she landed the job at the California Institute of Technology's Jet Propulsion Lab, where she has spent the last 30 years slowly but surely moving up, eventually being named Mars program manager. There are wonderful narrative bits in the course of building the rover: budgets slashed, impossible deadlines, shouting matches with rival managers outto sink rover, and plenty of how-we-did-it-with-chewing-gum-and-sticky-tape solutions. But there's also a special appeal for women in this saga: Shirley is of a prefeminist generation. She had a lifelong dream of getting to Mars and discovered that sheer hard work, respect for talent, and well-honed management skills got her there. Never say die!\ \