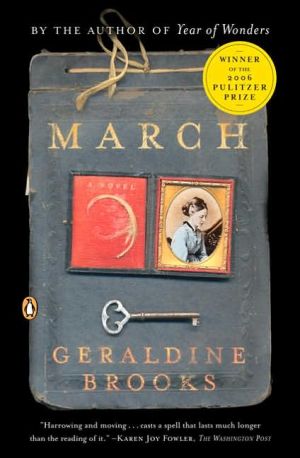

March

From Louisa May Alcott’s beloved classic Little Women, Geraldine Brooks has animated the character of the absent father, March, and crafted a story "filled with the ache of love and marriage and with the power of war upon the mind and heart of one unforgettable man" (Sue Monk Kidd). With"pitch-perfect writing" (USA Today), Brooks follows March as he leaves behind his family to aid the Union cause in the Civil War. His experiences will utterly change his marriage and challenge his most...

Search in google:

From Louisa May Alcott’s beloved classic Little Women, Geraldine Brooks has animated the character of the absent father, March, and crafted a story “filled with the ache of love and marriage and with the power of war upon the mind and heart of one unforgettable man” (Sue Monk Kidd). With “pitch-perfect writing” (USA Today), Brooks follows March as he leaves behind his family to aid the Union cause in the Civil War. His experiences will utterly change his marriage and challenge his most ardently held beliefs. A lushly written, wholly original tale steeped in the details of another time, March secures Geraldine Brooks’s place as a renowned author of historical fiction. “A very great book... It breathes new life into the historical fiction genre [and] honors the best of the imagination.” —Chicago Tribune“A beautifully wrought story about how war dashes ideals, unhinges moral certainties and drives a wedge of bitter experience and unspeakable memories between husband and wife.” —Los Angeles Times Book Review“Inspired... A disturbing, supple, and deeply satisfying story, put together with craft and care and imagery worthy of a poet.” —The Cleveland Plain Dealer“Louisa May Alcott would be well pleased.” —The EconomistThe Washington Post - Karen Joy FowlerBrooks has taken a chance in evoking it so strongly at the end, but the chance pays off beautifully. March is an altogether successful book, casting a spell that lasts much longer than the reading of it.

chapter one\ Virginia Is a Hard Road\ October 21, 1861\ This is what I write to her: The clouds tonight embossed the sky. A dipping sun gilded and brazed each raveling edge as if the firmament were threaded through with precious filaments. I pause there to mop my aching eye, which will not stop tearing. The line I have set down is, perhaps, on the florid side of fine, but no matter: she is a gentle critic. My hand, which I note is flecked with traces of dried phlegm, has the tremor of exhaustion. Forgive my unlovely script, for an army on the march provides no tranquil place for reflection and correspondence. (I hope my dear young author is finding time amid all her many good works to make some use of my little den, and that her friendly rats will not grudge a short absence from her accustomed aerie.) And yet to sit here under the shelter of a great tree as the men make their cook fires and banter together provides a measure of peace. I write on the lap desk that you and the girls so thoughtfully provided me, and though I spilled my store of ink you need not trouble to send more, as one of the men has shown me an ingenious receipt for a serviceable substitute made from the season's last blackberries. So am I able to send "sweet words" to you!\ Do you recall the marbled endpapers in the Spenser that I used to read to you on crisp fall evenings just such as this? If so, then you, my dearest one, can see the sky as I saw it here tonight, for the colors swirled across the heavens in just such a happy profusion.\ And the blood that perfused the silted eddies of the boot-stirred river also formed a design that is not unlike those fine endpapers. Or-better-like that spill of carmine ink when the impatient hand of our little artist overturned the well upon our floorboards. But these lines, of course, I do not set down. I promised her that I would write something every day, and I find myself turning to this obligation when my mind is most troubled. For it is as if she were here with me for a moment, her calming hand resting lightly upon my shoulder. Yet I am thankful that she is not here, to see what I must see, to know what I am come to know. And with this thought I exculpate my censorship: I never promised I would write the truth.\ I compose a few rote words of spousal longing, and follow these with some professions of fatherly tenderness: All and each of you I have in my mind, in parlor, study, chambers, lawn; with book or with pen, or hand in hand with sister dear, or holding talk the while of father, a long way off, and wondering where he is and how he does. Know that I can never leave you quite; for while my body is far away my mind is near and my best comfort is in your affection...Then I plead the press of my duties, closing with a promise soon to send more news.\ My duties, to be sure, are pressing enough. There are needful men all around me. But I do not immediately close my lap desk. I let it lie across my knees and continue to watch the clouds, their knopped masses blackened now in the almost lightless sky. No wonder simple men have always had their gods dwell in the high places. For as soon as a man lets his eye drop from the heavens to the horizon, he risks setting it on some scene of desolation.\ Downriver, men of the burial party wade chest deep to retrieve bodies snagged on fallen branches. Contrary to what I have written, there is no banter tonight, and the fires are few and ill tended, so that the stinging smoke troubles my still-weeping eye. There is a turkey vulture staring at me from a limb of sycamore. They have been with us all day, these massive birds. Just this morning, I had thought them stately, in the pearly predawn light, perched still as gargoyles, wings widespread, waiting for the rising sun. They did not move through all the long hours of our Potomac crossing, first to our muster on this island, which sits like a giant barge in the midstream, splicing the wide water into rushing narrows. They watched, motionless still, as we crossed to the farther shore and made our silent ascent up the slippery cow path on the face of the bluff. Later, I noticed them again. They had taken wing at last, inscribing high, graceful arcs over the field. From up there, at least, our predicament must have been plain: the enemy in control of the knoll before us, laying down a withering fire, while through the woods to our left more troops moved in stealthy file to flank us. As chaplain, I had no orders, and so placed myself where I believed I could do most good. I was in the rear, praying with the wounded, when the cry went up: Great God, they are upon us!\ I called for bearers to carry off the wounded men. One private, running, called to me that any who tried it would be shot full of more bullets than he had fingers and toes. Silas Stone, but lightly injured then, was stumbling on a twisted knee, so I gave him my arm and together we plunged into the woods, joining the chaos of the rout. We were trying to recover the top of the cow path-the only plain way down to the river-when we came upon another turkey vulture, close enough to touch it. It was perched on the chest of a fallen man and turned its head sharply at our intrusion. A length of organ, glossy and brown, dangled from its beak. Stone raised his musket, but he was already so spent that his hands shook violently. I had to remind him that if we didn't find the river and get across it, we, too, would be vulture food.\ We thrashed our way out of the thicket atop a promontory many rods short of the cow path. From there, we could see a mass of our men, pushed by advancing fire to the very brow of the bluff. They hesitated there, and then, of a sudden, seemed to move as one, like a herd of beasts stampeded. Men rolled, leaped, stumbled over the edge. The drop is steep: some ninety feet of staggered scarps plunging to the river. There were screams as men, bereft of reason, flung themselves upon the heads and bayonets of their fellows below. I saw the heavy boot of one stout soldier land with sickening force onto the skull of a slight youth, mashing the bone against rock. There was no point now in trying to reach the path, since any footholds it might once have afforded were worn slick by the frenzied descent. I crawled to the edge of the promontory and dangled from my hands before dropping hard onto a narrow ledge, all covered with black walnuts. These sent me skidding. Silas Stone rolled and fell after me. It wasn't until we reached the water-laved bank that he told me he could not swim.\ The enemy was firing from the cliff top by then. Some few of our men commenced tying white rags to sticks and climbing back up to surrender. Most flung themselves into the river; many, in their panic, forgetting to shed their cartridge boxes and other gear, the weight of which quickly dragged them under. The only boats were the two mud scows that had ferried us across. For these, men flung themselves until they were clinging as a cluster of bees dangling from a hive, and slipping off in clumps, four or five together. Those that held on were plain targets and did not last long.\ I dragged off my boots and made Stone do the same, and bade him hurl his musket far out, to the deepest channel, so as to put it from reach of our enemies. Then we plunged into the chill water and struck out toward the island. I thought we could wade most of the way, for crossing at dawn, the poles had seemed to go down no significant depth. But I had not accounted for the strength of the current, nor the cold. "I will get you across," I had promised him, and I might have done, if the bullet hadn't found him, and if he hadn't thrashed so, and if his coat, where I clutched it, hadn't been shoddily woven. I could hear the rip of thread from thread, even over the tumbling water and the yelling. His right hand was on my throat, his fingers-callused tradesman's fingers-depressing the soft, small bones around my windpipe. His left hand clutched for my head. I ducked, trying vainly to refuse him a grip, knowing he would push me under in his panic. He managed to snatch a handful of my hair, his thumb, as he did so, jabbing into my left eye. I went under, and the mass of him pushed me down, deep. I jerked my head back, felt a burn in my scalp as a handful of hair ripped free, and my knee came up, hard, into something that gave like marrow. His hand slid from my throat, the jagged nail of his middle finger tearing away a piece of my skin.\ We broke the surface, spewing red-brown water. I still had a grip on his tearing jacket, and if he had stopped his thrashing, even then, I might have seized a stouter handful of cloth. But the current was too fast there, and it tugged apart the last few straining threads. His eyes changed when he realized. The panic just seemed to drain away, so that his last look was a blank, unfocused thing-the kind of stare a newborn baby gives you. He stopped yelling. His final sound was more of a long sigh, only it came out as a gargle because his throat was filling with water. The current bore him away from me feet first. He was prone on the surface for a moment, his arms stretched out to me. I swam hard, but just as I came within reach a wave, turning back upon a sunken rock, caught his legs and pushed the lower half of his body under, so that it seemed he stood upright in the river for a moment. The current spun him round, a full turn, his arms thrown upward with the abandon of a Gypsy dancer. The firing, high on the bluff, had loosed showers of foliage, so that he swirled in concert with the sunshine-colored leaves. He was face to face with me again when the water sucked him under. A ribbon of scarlet unfurled to mark his going, widening out like a sash as the current carried him, down and away. When I dragged myself ashore, I still had the torn fragment of wet wool clutched in my fist.\ I have it now: a rough circle of blue cloth, a scant six inches across. Perhaps the sum total of the mortal remains of Silas Stone, wood turner and scholar, twenty years old, who grew up by the Blackstone River and yet never learned to swim. I resolved to send it to his mother. He was her only son.\ I wonder where he lies. Wedged under a rock, with a thousand small mouths already sucking on his spongy flesh. Or floating still, on and down, on and down, to wider, calmer reaches of the river. I see them gathering: the drowned, the shot. Their hands float out to touch each other, fingertip to fingertip. In a day, two days, they will glide on, a funeral flotilla, past the unfinished white dome rising out of its scaffolds on a muddy hill in Washington. Will the citizens recognize them, the brave fallen, and uncover in a gesture of respect? Or will they turn away, disgusted by the bloated mass of human rot?\ I should go now and find out where upon this island they are tending to the wounded. Naturally, the surgeon has not seen fit to send me word. The surgeon is a Calvinist, and a grim man, impatient with unlabeled brands of inchoate faith. In his view, a man should be a master of his craft, so that a smith should know his forge, a farmer his plow, and a chaplain his creed. He has made plain his disregard for me and my ministry. The first time I preached to the company, he observed that in his view a sermon that did not dwell on damnation was scant service to men daily facing death, and that if he wanted to hear a love poem he would apply to his wife.\ I dragged a hand through my hair, which has dried out in tangled mats, like discarded corn silks at a husking. Even to raise my arm for that slight effort is a misery. Every muscle aches. My aunt was right, perhaps, in her bitter denunciation of my coming here: the cusp of a man's fortieth year is no season for such an enterprise as this. And yet what manner of man would I be, who has had so much to say in the contest of words, if now I shirked this contest of blood? So I will stand here with those who stand in arms, as long as my legs can support me. But, as a private from Millbury observed to me today, "Virginia is a hard road, reckon."\ I stowed the lap desk in my rucksack. We had left the main part of our gear here on the island, but my blanket was sodden from the use of it to dry myself and to blot my soaking clothes. Still, there is some warmth in wool, wet or no. I carried it to a youth who lay, curled and keening, on the riverbank. The boy was dripping wet and shivering. I expected he would be on fire with fever by morning. "Will you not come up the bank with me to some drier ground?" I asked. He made no reply, so I tucked the blanket around him where he lay. We will both sleep cold tonight. And yet not, I think, as cold as Silas Stone.\ I made my way a few rods through the mud and then, where the bank dipped a little, scrambled with some difficulty into a mown field. In the flicker of firelight I discerned a small band of walking wounded sitting listless in the hollows of a haystack where they would shiver out the night. I inquired from them where the hospital tents had been established. 'There ain't no tents: they're using some old secesh house,' said a private, nursing a bandaged arm. 'Strange place it is, with big white statues all nekked, and rooms filled up with old books. There's an old secesh lives there, cracked as a clay pot dropped on rock, seemingly, with just one slave doing for him. She's helping our surgeon, if you'd credit it. She probed out my wound for me and bound it up fine, like you see,' he said, proudly raising his sling, then wincing as he did so. 'She told me they was more than a dozen slaves on the place before, and she the only one ain't ran off.'\ I don't think the private knew his left from right, for his directions to the house were less than coherent, and his friend, whose neck was bandaged and who couldn't speak, kept waving his hands in objection at every turn the other man described. So I blundered on in the dark, finding myself at the riverbank again, uncertain whether the farther shore was Maryland or Virginia. I turned back and found a line of snake-rail fence that led past the ruins of what must have once been a gristmill. I continued following the fence line until it turned in at a gate. Beyond stretched a drive lined with dogwoods, and a gravel of river stone that was hard on my bootless feet.\ And then I knew I was on the right path, for I smelled it. If only field hospitals did not always have the selfsame reek as latrine trenches. But so it is when metal lays open the bowels of living men and the wastes of digestion spill about. And there is, too, the lesser stink, of fresh-butchered meat, which to me is almost equally rank. I stopped, and turned aside into the bushes, and heaved up bitter fluid. Something about my state just then, bent double and weak, brought to my mind the recollection of my father, caning me, for refusing my share of salt pork. He believed a meatless diet such as mine made me listless at my chores. But what I shirked were the tasks themselves, foul and cruel. No soul should be asked to toil all day with the yellow oxen yoked up, unwilling, their hide worn raw by the harness, their big blank eyes empty of hope. It drains the spirit, to trudge sunup till sundown at the arse-end of beasts, sinking into piles of their steaming ordure. And the pigs! How could anyone eat pork who has heard the screams at slaughter when the black blood spurts?\ Perhaps it was the darkness, or the different season. Perhaps my biliousness and grief and exhaustion. Perhaps simply that twenty years is a very long time for an active mind to retain any memory, much less one with dark and troubled edges, begging to be forgot. Whatever the case, I was halfway up the wide stone steps before I recognized the house. I had been there before.

\ Thomas MallonGeraldine Brook's second novel is in every important way less accomplished than her first, Year of Wonders (2001). That book, which dealt with the assaults of plague on a 17th-century English village, derived some of its power from the way its resourceful heroine came to suspect the biological essence of the calamity she was up against: ''Perhaps the Plague was neither of God nor the Devil, but simply a thing in Nature, as the stone on which we stub a toe.'' Fearlessness -- and experimentation with herbs -- saw her through and won a reader's respect. In March, the ferocious nemeses conjured by Brooks are war and slavery, which, unlike impersonal disease, end up prompting the author and her characters toward a prolonged moral exhibitionism.\ — The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Karen Joy FowlerBrooks has taken a chance in evoking it so strongly at the end, but the chance pays off beautifully. March is an altogether successful book, casting a spell that lasts much longer than the reading of it.\ — The Washington Post\ \ \ Publishers WeeklyBrooks's luminous second novel, after 2001's acclaimed Year of Wonders, imagines the Civil War experiences of Mr. March, the absent father in Louisa May Alcott's Little Women. An idealistic Concord cleric, March becomes a Union chaplain and later finds himself assigned to be a teacher on a cotton plantation that employs freed slaves, or "contraband." His narrative begins with cheerful letters home, but March gradually reveals to the reader what he does not to his family: the cruelty and racism of Northern and Southern soldiers, the violence and suffering he is powerless to prevent and his reunion with Grace, a beautiful, educated slave whom he met years earlier as a Connecticut peddler to the plantations. In between, we learn of March's earlier life: his whirlwind courtship of quick-tempered Marmee, his friendship with Emerson and Thoreau and the surprising cause of his family's genteel poverty. When a Confederate attack on the contraband farm lands March in a Washington hospital, sick with fever and guilt, the first-person narrative switches to Marmee, who describes a different version of the years past and an agonized reaction to the truth she uncovers about her husband's life. Brooks, who based the character of March on Alcott's transcendentalist father, Bronson, relies heavily on primary sources for both the Concord and wartime scenes; her characters speak with a convincing 19th-century formality, yet the narrative is always accessible. Through the shattered dreamer March, the passion and rage of Marmee and a host of achingly human minor characters, Brooks's affecting, beautifully written novel drives home the intimate horrors and ironies of the Civil War and the difficulty of living honestly with the knowledge of human suffering. Agent, Kris Dahl. 10-city author tour. (Mar. 7) Copyright 2004 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalIn Louisa May Alcott's Little Women, readers see a perfect, self-sacrificing, loving, close-knit family. Brooks here concentrates on the absent father. Referring to him as simply March, Brooks creates a picture of his struggle with his not-so-perfect life during his tour of duty as a chaplain on the Civil War battlefields of Virginia. What emerges is the complex conflict of a man of principle who must adjust to fit the reality he encounters. March wrestles with hatred, evil, violence, ignorance, rage, lust, illness, and competing loyalties, from both outside himself and within. The author's extensive research provides the details of time and place that make this tale so compelling. Richard Easton's delivery is flawless-the characters are complex, their encounters, realistic. Recommended.-Joanna M. Burkhardt, Coll. of Continuing Education Lib., Univ. of Rhode Island, Providence Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ School Library JournalAdult/High School-In Brooks's well-researched interpretation of Louisa May Alcott's Little Women, Mr. March also remains a shadowy figure for the girls who wait patiently for his letters. They keep a stiff upper lip, answering his stiff, evasive, flowery letters with cheering accounts of the plays they perform and the charity they provide, hiding their own civilian privations. Readers, however, are treated to the real March, based loosely upon the character of Alcott's own father. March is a clergyman influenced by Thoreau, Emerson, and especially John Brown (to whom he loses a fortune). His high-minded ideals are continually thwarted not only by the culture of the times, but by his own ineptitude as well. A staunch abolitionist, he is amazingly naive about human nature. He joins the Union army and soon becomes attached to a hospital unit. His radical politics are an embarrassment to the less ideological men, and he is appalled by their lack of abolitionist sentiments and their cruelty. When it appears that he has committed a sexual indiscretion with a nurse, a former slave and an old acquaintance, March is sent to a plantation where the recently freed slaves earn wages but continue to experience cruelty and indignities. Here his faith in himself and in his religious and political convictions are tested. Sick and discouraged, he returns to his little women, who have grown strong in his absence. March, on the other hand, has experienced the horrors of war, serious illness, guilt, regret, and utter disillusionment.-Jackie Gropman, Chantilly Regional Library, VA Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsBrooks combines her penchant for historical fiction (Year of Wonders, 2001, etc.) with the literary-reinvention genre as she imagines the Civil War from the viewpoint of Little Women's Mr. March (a stand-in for Bronson Alcott). In 1861, John March, a Union chaplain, writes to his family from Virginia, where he finds himself at an estate he remembers from his much earlier life. He'd come there as a young peddler and become a guest of the master, Mr. Clement, whom he initially admired for his culture and love of books. Then Clement discovered that March, with help from the light-skinned, lovely, and surprisingly educated house slave Grace, was teaching a slave child to read. The seeds of abolitionism were planted as March watched his would-be mentor beat Grace with cold mercilessness. When March's unit makes camp in the now ruined estate, he finds Grace still there, nursing Clement, who is revealed to be, gasp, her father. Although drawn to Grace, March is true to his wife Marmee, and the story flashes back to their life together in Concord. Friends of Emerson and Thoreau, the pair became active in the Underground Railroad and raised their four daughters in wealth until March lost all his money in a scheme of John Brown's. Now in the war-torn South, March finds himself embroiled in another scheme doomed to financial failure when his superiors order him to minister to the "contraband": freed slaves working as employees for a northerner who has leased a liberated cotton plantation. The morally gray complications of this endeavor are the novel's greatest strength. After many setbacks, the crop comes in, but the new plantation-owner is killed by marauders and his "employees" taken back intoslavery. March, deathly ill, ends up in a Washington, DC, hospital, where Marmee visits and meets Grace, now a nurse. Readers of Little Women know the ending. The battle scenes are riveting, the human drama flat. Author tour\ \