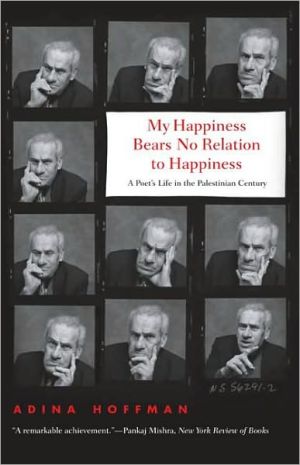

My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet's Life in the Palestinian Century

Beautifully written, and composed with a novelist’s eye for detail, this book tells the story of an exceptional man and the culture from which he emerged.\ Taha Muhammad Ali was born in 1931 in the Galilee village of Saffuriyya and was forced to flee during the war in 1948. He traveled on foot to Lebanon and returned a year later to find his village destroyed. An autodidact, he has since run a souvenir shop in Nazareth, at the same time evolving into what National Book Critics Circle...

Search in google:

Beautifully written, and composed with a novelist’s eye for detail, this book tells the story of an exceptional man and the culture from which he emerged. Taha Muhammad Ali was born in 1931 in the Galilee village of Saffuriyya and was forced to flee during the war in 1948. He traveled on foot to Lebanon and returned a year later to find his village destroyed. An autodidact, he has since run a souvenir shop in Nazareth, at the same time evolving into what National Book Critics Circle Award–winner Eliot Weinberger has dubbed “perhaps the most accessible and delightful poet alive today.” As it places Muhammad Ali’s life in the context of the lives of his predecessors and peers, My Happiness offers a sweeping depiction of a charged and fateful epoch. It is a work that Arabic scholar Michael Sells describes as “among the five ‘must read’ books on the Israel-Palestine tragedy.” In an era when talk of the “Clash of Civilizations” dominates, this biography offers something else entirely: a view of the people and culture of the Middle East that is rich, nuanced, and, above all else, deeply human. The Barnes & Noble Review Poetry is what gets lost in translation -- and also what slips through the historian's net. The attention of a biographer, after all, tends to be fixed on the facts of a poet's life, rather than on the form of his line. That much I remember from learning to read in the old literary school called New Criticism, which insisted that the meaning of a poem was the poem itself. And for the most part those strictures still ring true. But the contemporary Palestinian author Taha Muhammad Ali has been wonderfully served by his translators, so that his works in English still have what someone once identified as the defining effect of great poetry, which is to make the hair on the back of your neck stand up. Now, with Adina Hoffman's My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet's Life in the Palestinian Century, we have a book that enriches the appreciation of his work, rather than using it as an occasion for political commentary on the Middle East. (Not so coincidentally, the poet's biographer is married to Peter Cole, one of the translators of Ali's So What: New and Selected Poems, 1971-2005.)

MY HAPPINESS BEARS NO RELATION TO HAPPINESS\ A Poet's Life in the Palestinian Century \ \ By Adina Hoffman \ Yale University Press\ Copyright © 2009 Adina Hoffman\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-300-14150-4 \ \ \ Chapter One\ MAP OF A VANISHED TOWN \ * * *\ WITH A TITLE AS HAUNTED AND HAUNTING as its subject matter, All That Remains is a monumental reference book, in which the distinguished historian Walid Khalidi and a team of researchers set out to chronicle the 418 Palestinian villages that Israel effectively erased in 1948. A painstakingly compiled document that is all the more moving for its matter-of-factness, the book offers photographs and brief, businesslike descriptions of each of these villages-before '48, during the war, and today-and in doing so it attempts to preserve on paper what has disappeared from the earth: "Now and then a few crumbled houses are left standing, a neglected mosque or church, collapsing walls along the ghost of a village lane, but in the vast majority of cases, all that remains is a scattering of stones across a forgotten landscape." The book is, says the preface, "an attempt to record that lost world."\ There is in this effort an air both of urgency and of futility: if these facts aren't set down now, the authors seem to be saying, they will be gone forever; on the other hand, it is clear-as it is clearto anyone who has spent time trying to account in words for a way of life that no longer exists-that the book cannot ever be more than "an attempt." Too many traces have already been destroyed or washed away; too much time has passed; too many witnesses have sunken into silence, forgotten, or died.... Venturing to reconstruct the years of Taha's childhood and adolescence, or to imagine Saffuriyya in all its vanished richness and complication, is of course a similar task, and as I work (interviewing, translating and transcribing those interviews, sifting through archival files, combing footnotes and card catalogues, Xeroxing, looping microfilm onto spools, poring through old journals and newspapers) I sometimes feel myself an archaeologist, entrusted with an especially precious-but partial and vulnerable-to-the-elements-mound of chipped relics and fragmented memories, each of which must be examined and gingerly placed in a pattern that makes some kind of sense.\ There are obstacles. "Arkhas hibr, afdal min idh-dhikr" (the cheapest ink is better than memory), as Amin, Taha's then-seventy-year-old and youngest brother, once told me, explaining his own passionate work as amateur historian and president of the Saffuriyya Heritage Society, a cultural-political group he founded with several friends in 1993. Among the society's goals is to salvage the remnants of the material and human past of Saffuriyya and other obliterated villages like it, through the preservation of oral history and the collection of daily objects. One floor of Amin's Nazareth house is home to the society's offices and a remarkable, single-room museum. This is a generic, almost corporate space with fluorescent lights, fiberglass ceilings, and shiny tile floors-filled almost to bursting with the incongruously preindustrial and heartbreakingly modest paraphernalia of pre-1948 Galilee village life: baskets and mortars, shaving kits and wooden dowry boxes, a gauzy woman's headscarf, trimmed with a dainty, handmade menagerie of silk-thread birds and flowers. Amin has, it seems, paid for much of this collection out of his own pocket, and driven himself into debt in the process. When he sees an old Palestinian object, he must have it for the museum-rescue it, as it were, from near-certain oblivion and so somehow restore it to its proper place in the order of things. (He himself doesn't talk in such cosmic terms but does admit to the slightly obsessive nature of his collecting.) He has also single-handedly performed a kind of oral-history triage, as he realized that he had to act right away or else the older people would take with them to the grave irreplaceable information about the village-the popular names, for instance, for the different parts of town. Almost every plot in Saffuriyya was known to the villagers by a name based on its past or present owners (Khallet ish-Sheikh Hassan, Sheikh Hassan's Knoll), what grew there (Juret iz-za'tar, Hyssop Gulley), or some more mysterious association (Balatet il-hayyeh, the Stone of the Snake).\ At some point in the 1990s, Amin told me, he realized that "the old people are dying, and those names will disappear. I told myself I have no choice. I'll ask them: What do you remember of the names from the village? I'll write it down. From here ten names, from there twenty names, from there thirty, from there fifteen.... Then I'd go back and say, okay, we're in Saffuri, we want to go to Shafa 'Amr [the next large village]-what is the name of the first block? The first parcel of land, what's it called? And what's after it? And after that? And after? And how big was this one? And this? It wasn't exact. But how much, approximately? I worked on this list for maybe two years. And the names I didn't write down are gone." In a similar inch-by-inch way, he went from house to house around Nazareth-where today some fifteen thousand of the city's sixty thousand residents count themselves as Saffuriyyans, or descendants of Saffuriyyans-and transcribed what the older people remembered of the names and owners of the village thoroughbreds, the names of the teachers in the village school.... As he worked, word of his fascination with the town's history spread, and aging former villagers sought him out and presented him with priceless documents: one man had been responsible in the early 1940s for water distribution in the orchards and had kept a detailed notebook, listing the sizes and owners of the various plots. When the Israeli army occupied Saffuriyya in 1948, the man fled to Nazareth, but in the days immediately following the conquest, he managed to sneak back into his house and rescue the notebook, whose previously humdrum subject matter (irrigation) had been transformed in the course of that fateful week into the most valuable sort of written proof-sentimental proof of an eclipsed way of life but also potentially legal proof of land ownership. Now, almost fifty years after Saffuriyya was leveled, he handed the notebook over for safekeeping to Amin-that is, to posterity.\ But as Amin is the first to admit, such systematically kept written records were the exception in the village and not the rule. Saffuriyya was an almost entirely oral place, and written documentation of the village-of the sort biographers tend to take for granted when constructing timelines and portraits of their subjects-simply does not exist. The village had no local newspaper, no records office, no medical files, no school yearbook. None of Taha's relatives or friends kept date books or diaries or wrote newsy letters to out-of-town aunts; his mother hung no smiling wedding pictures from her walls, and she did not memorialize her children's growth in a scrapbook or photo album. And whatever private papers of Taha's that might once have existed-his report cards, his first attempts at writing, the single photograph taken of him as a child-were destroyed when the village was destroyed.\ "We have a problem. Our problem is that our people aren't historians. We depend on listening. You hear a story, and you tell it, and distort it. You add to it, you take away from it," says Amin, and aside from the information and old photographs that he himself has valiantly gathered and that the Saffuriyya Heritage Society printed in two glossy magazines and a wall calendar, the written vestiges of the village are sketchy in the extreme: recently a former villager published a catch-all collection of Saffuriyya history and lore-which includes folk songs, family names, pictures of ancient coins and oil lamps found in the village, a chronicle of "Saffuriyya during the Crusader Aggression," lists of local birds, the "martyrs" killed in 1948, herbal medicine prescriptions, wedding customs, and so on. And another slender memorial volume was compiled in Syria by two refugees who live there and whose work is apparently unknown to their former neighbors, the Saffuriyyans in Israel. (I stumbled on a copy while browsing in the stacks of a large American university library.)\ Beyond that, the only paper trail left by the village is a thin, fascinating, and distinctly misleading one-which passes through archives now housed in Israel and England. (The British controlled Palestine from 1917 until 1948-the period known now simply as the Mandate-and when they decamped in the chaos of that last year, they took some files with them, burned some, and left others behind, in uncharacteristically pell-mell fashion.) These records provide a glimpse into the life of the village that is, on the one hand, marvelously concrete-not precarious and shifting like memory and so an exciting discovery for someone trying to rebuild the village, as it were, on the page. The tabletop-sized Mandate-era Nazareth police station logs that have survived the years, for instance, offer the most tangible facts about the people and pulse of the village-who bullied who, who cheated who, who beaned who with a rock at exactly what hour on what day.... But as these few examples indicate, and as logic dictates, the only sort of events that are preserved in the law enforcement files are the grumbling, ugly ones: this is merely a story of grievances and arrests. And though the tale told by these records is no doubt true-and important to account for, somehow, as one tries to conjure the village-it also leaves out the contented, day-in-day-out, uncomplaining side of Saffuriyya. And according to the people who lived there, this was the place they knew and loved.\ The villagers entered the written record only when they were dealing with the outside world, which is to say, when something went wrong. Besides the fistfights and robberies recorded in the police logs, various "crimes" are set down there that seem, in retrospect, to implicate the English authorities more than the villagers. The strict legalism of the Mandatory system grated against the villagers' traditional way of life, so that, for instance, the police could often be found charging the people of Saffuriyya with "harvesting and threshing wheat without a permit" and "picking olives before the date appointed by the Administrative Office." In one case, a charge of "Illegal Celebration of a Marriage" is noted, followed by a brief, cryptic explanation: "Secret information that 4 girls were married under age in Saffourieh. All X-rayed, found to be under 15 years old."\ Other loaded interactions are preserved in innocuous-sounding files like the one called "Saffuria Roads," now housed in the Israel State Archive. There one finds the lengthy correspondence between the Saffuriyya local council and the British high commissioner about the urgent need to pave the single road that connected Saffuriyya with the towns nearby-with, in other words, that very outside world. This exchange kicks off with a respectful 1935 letter, written in literary Arabic and translated by a Mandatory clerk into slightly stilted English:\ During your last visit to Saffuriya, Your Excellency noted how large is our village with its numerous inhabitants, large areas of lands [sic] sufficient water and vast gardens. On your return to Jerusalem Your Excellency have [sic] kindly ordered your local representatives to expend a certain amount on leveling the road to our village. Whereas we have important commercial relations with the towns of Haifa, Acre, Nazareth, and Tiberias to which our vegetables, fruits and animals are exhibited for sale, therefore we have no easy connection with the said towns in view of the fact that the licensed busses of our village are unable to pass the said road which is now muddy from rains.\ After their request was summarily rejected by the district commissioner on what appear to be financial grounds, the bus owners themselves began to complain, since their business was suffering during the rainy season, and by 1937 the town's mayor, Sheikh Saleh Salim Sulayman, and the council were driven to write another-much testier, and surprisingly political-letter to His Excellency:\ We suggest that because we are native landlords, the Public Works Department did not take an interest in this matter, while for the interest of the Jews a road from Ginesar to Nahalal is being constructed which will cost Government twenty two thousand pounds and another road from Afula to Shatta which will also cost double the expenses of the other roads.... Seeing this injustice, we humbly complain to Your Excellency against the action of the Public Works Department.\ More than a decade after the council's first letter on the subject had been delivered to Jerusalem, the road was still washing out, complaints were registered that doctors couldn't get through to the village, and the district commissioner finally wound around to recommending a loan to the council for the long-awaited pavement. His reasoning, though, is startling in its steeliness. After admitting that the village is indeed "one of the principal suppliers for the vegetable markets of Haifa and [that] a considerable amount of commercial traffic proceeds in and out of the local council area daily," he gets down to what's really on his mind:\ I would also add that in the event of a recrudescence of disorders on the Arab Side, Saffuriyya would undoubtedly be the chief center in the Nazareth area of organised resistance to Government, and the existence of a fast asphalted approach road would be of considerable assistance to the forces of law and order.\ Even the logic of so-called security didn't win out, though: the loan was declined, 1948 soon arrived, and it seems the village never got its asphalt.\ Sheikh Saleh and the council make frequent appearances in the files. They were, after all, the village's official representatives before the Powers That Were. In only a few instances do the people of Saffuriyya speak for themselves. Aside from several appeals on behalf of prisoners and the desperate letter of a father about the disappearance of his two boys-one of whom is preserved forever in epistolary amber as a fourteen-year-old, "wearing khaki trousers and a shirt under a yellow kumbaz [robe]" when he was last seen-there is, as far as I can tell, a single file that contains letters from ordinary citizens. Though it should be said here that the archives themselves are vast haystacks containing who-knows-how-many-needles: the Israel State Archive in particular holds a treasure trove of Mandate-era documents-everything from files called Maronite Monks to Field Mice, Erection of Electric Poles, Bomb Outrages, Nutrition in the Colonial Empire, Enumeration of Goats, Lunatics, Playing Cards, Stamp Vendors, Alleged Discovery of Gold in Palestine, Preservation of Public Morality, Search for Buried Treasures, and Manufacture and Sale of Whipped Cream.\ But at the time of my work there, the archive lacked a centralized cataloguing system, and to find any trace of the village at all one had to pore over long, irregular, and often incorrectly typed or scribbled (half-Hebrew, half-English) lists under an assortment of headings and flip through unalphabetized, handwritten card catalogues in search of the place, spelled variably as Saffuriyya, Saffuriya, Safuriya, Safuriyeh, Saffurieh, Saffourieh, Safourieh, Safuria, Saffuria, and by its Hebrew name, Tzippori, Tsippori, Zippori-not to be confused with a different village, in the Jaffa District, called Safiriyya or Safiriya. Each file had to be ordered up from the vaults, at which point one would inevitably be told that certain documents were "missing" or off-limits because of their fragile state. The folders that did arrive-their contents sometimes crumbling or preserved in the faintest carbon copy-had then to be sorted through carefully for clues. It seems almost certain that the archive contains other mentions of the village that I have not unearthed or been able to decipher.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from MY HAPPINESS BEARS NO RELATION TO HAPPINESS by Adina Hoffman Copyright © 2009 by Adina Hoffman. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Prelude: Bir el-Amir 1Saffuriyya I 11Saffuriyya II 65Lebanon 135Reina 171Nazareth I 187Nazareth II 295List of Illustrations 406Notes 409Acknowledgments 443Index 447

\ Dwight GarnerMy Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness is a book I'm glad to have. It communicates Ms. Hoffman's enthusiasm for this unusual poet, and sends us running to read the work of the talented man she describes, accurately enough, as "equal parts clown and king."\ —The New York Times\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyThat his happiness bears a strong relationship to dispossession and exile makes Israeli Arab poet Taha Muhamad Ali, subject of this luminous biography, an iconic voice of the Palestinian consciousness. The 17-year-old Taha and his family lost their home when the Israeli army captured and demolished their village, Saffuriyya, in 1948. After a lifetime spent running a souvenir shop in Nazareth, he has recently won international acclaim for his poetry. Intersecting his perceptions with Hoffman's own account of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict (which sometimes favors the Palestinians), Israeli-American essayist Hoffman (House of Windows: Portraits from a Jerusalem Neighborhood) uses his story as the starting point for a painterly reconstruction of the lost world of Saffuriyya and its diaspora. Hoffman is a perceptive reader of Taha's work (which she places in the context of a dynamic Palestinian literary scene) , appreciating its formal inventiveness, its dapplings of melancholy and exuberance, and its grounding in the pungent details and vernacular of village life. Looking past the usual strident politics, Hoffman presents readers with a subtle, moving evocation of the human realities of the Palestinian experience, rooted in land and memory. Photos. (Apr.)\ Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.\ \ \ Library JournalIn the fog of the Israel-Palestine predicament, which is heavily burdened by conflicting personal and national narratives, very few Middle Eastern writers succeed in offering the kind of literature that is imbued with a mutually accepted and shared view of the rich culture and people of the region. Leading Palestinian poet-and Israeli citizen-Taha Muhammad Ali is that rare figure who possesses a poet's vision of experience that is equally applicable to Arabs and Jews. He is esteemed among Arabic readers in Israel and Palestine for his rich, politically complex, and sensitive work. As this biography demonstrates, his writing (fiction as well as the poetry for which he is celebrated) emerges directly from the tragic stages of the Israeli-Arab conflict. While he is not a "protest poet," his poems show the power of beauty in difficult times in addition to the vivid imagination, humor, and honesty of a storyteller. Biographer, essayist, and literary critic Hoffman masterfully captures the life and work of this highly original poet. An exceptional introduction to a literary world that has, until now, been little known to English-language readers, this is highly recommended for all libraries.\ —Ali Houissa\ \ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsThe life and incendiary times of Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali, a secular Muslim and autodidact who lives in Israel, runs a souvenir shop in Nazareth and has somehow achieved and maintained an ecumenical, humane philosophy. Ibis Editions founder and editor Hoffman (Houses of Windows: Portraits from a Jerusalem Neighborhood, 2000) met Ali in 1995 with her husband Peter Cole, the poet's principal English translator. Since then she has pursued his story-not an easy task for an American-born Jew living in Jerusalem who initially knew no Arabic. During the past 13 years, she has learned the language, prowled civilian and military archives, walked the ground and interviewed countless individuals, probing their memories of cataclysmic events occurring more than a half-century ago. The result is not just a biography of a remarkable man, but a focused history of a region. Hoffman realizes the vast importance of displacement in Ali's story, most significantly during the 1948 war following the United Nations partition. That war resulted in the destruction of the poet's home village, Saffuriyya, and sent the 17-year-old and his family into temporary exile in Lebanon. There they suffered unspeakably with thousands of other refugees; Ali was separated from his betrothed and did not see her until decades later, when both had married others. His family returned to the land now called Israel in 1949; they were not allowed to go back to the ruins of their village and endured other severe restrictions. Possessing little formal schooling, Ali had an insatiable hunger for books; among his first purchases was a multivolume Arabic dictionary. He was in his 50s when he published his first collection ofpoems. Charting her subject's slow rise into a literary career, Hoffman pauses often, occasionally at great length, to expatiate upon the political, military and literary scene. A lovingly researched, well-rendered portrait that sometimes substitutes praise for analysis of the man and his work.\ \ \ \ \ booklistNamed one of the top ten biographies of 2009 by Booklist\ \ \ \ \ The Front TableSelected as one of best 20 books of the year by the Seminary Co-op\ \ \ \ \ New York Review of Books“[A] superb biography … a remarkable achievement.”—Pankaj Mishra, New York Review of Books\ \ \ \ \ Choice“[A] poignant, persuasive biography.”—Choice\ \ \ \ \ American Scholar“[This book] reads like a novel… a biography of a Palestinian writer and the sociopolitical events that informed and shaped him as well as a look at Palestinian cultural and literary history. But it is poetry that beats at the book’s heart—the way it moves inside of Muhammad Ali, around him, the way it surprises him and questions him as he questions it.”—The American Scholar\ \ \ \ \ The National"A triumph of sympathetic imagination, dogged research and impassioned writing. More than the story of one man's life [My Happiness] brings to light entire strata of historical and cultural experience that have been neglected or purposefully covered over. For readers of English there is no comparable work."–Robyn Creswell, The National\ \ \ \ \ Haaretz“Vivid and intimate, engrossing and full of memorable characters. Every scene [Hoffman] sketches comes alive.... Taha Muhammad Ali is fortunate to have had ... [her to] tell his story with such eloquence.”—Haaretz\ \ \ \ \ The Guardian“A rich tapestry of the personal, the literary and the political, skillfully woven by a sympathetic writer ... Hoffman's intense but often humorous book is a powerful reminder of the singularity and complexity of this most intractable of conflicts and of the ability of the human spirit to be creative in adversity."—The Guardian\ \ \ \ \ Booklist"Hoffman's lively, insightful, artistically contextualized portrait of a great and accessible poet provides a corrective perspective on Palestinian culture and offers new evidence of literature's transcendent power."—Booklist, starred review\ \ \ \ \ Times Literary Supplement"Beautifully written. . . . In tracing [Muhammad Ali's] life . . . Hoffman manages to illuminate the experience of an entire people. She is scrupulously even-handed. . . . [This] is not only the biography of a remarkable man; it is an act of reclamation against the erosions of memory."—Eric Ormsby, Times Literary Supplement\ \ \ \ \ Saudi Aramco World“Author Hoffman has done an admirable job of assembling this life story while it can still be told in the first person.”--Saudi Aramco World\ \ \ \ \ \ W.S. Merwin"Adina Hoffman's portrait of Taha Muhammad Ali brings to life character after character, each one viewed with the author's singular humanity. The poet himself is a figure of great originality and integrity, and his life becomes a mirror of a world which we have glimpsed, until now, largely in broken fragments. I hope this landmark book will be widely, and carefully, read."—W.S. Merwin \ \ \ \ \ Gerald Stern"From Adina Hoffman's extraordinary book, I have not only learned about the life of that wise, sweet, cunning, superbly gifted and totally original Palestinian poet, Taha Muhammad Ali, but I have learned—more than ever before—about Jewish and Arab history in Palestine. The book is heartbreaking, riveting, and beautifully written. Moreover it's one of a kind, courageous, and deeply honest."—Gerald Stern, National Book Award–winner for This Time: New and Selected Poems\ \ \ \ \ \ Maria Rosa Menocal"Adina Hoffman’s writing is historical magic. She relates world-scale political history on a human scale, so that the ‘Israeli-Palestinian’ conflict is rendered, with clarity and fairness, the story of one family, one village, one exodus, one return. At the end of the day, the meaning of this history is explored and contemplated in the ways a great novel achieves that kind of contemplation. A series of brilliantly told and searing stories, this is at once a page-turner and a book to be savored."—María Rosa Menocal, author of The Ornament of the World\ \ \ \ \ \ Azar Nafisi"Reading Adina Hoffman's remarkable book we are consoled that, in the face of terrible brutalities and sufferings, the enduring power of poetry might restore in words—and celebrate—a measure of what has been lost in reality."—Azar Nafisi, author of Reading Lolita in Tehran\ \ \ \ \ \ Michael Sells"Adina Hoffman has given us a superbly composed meditation upon memory, truth, and conflict in the Middle East. The texture of her prose, the improbable transformations of key characters, and above all their human depth and complexity, contribute to a luminous portrait of the Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali and of his world. I would place My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness among the five 'must read' books on the Israel-Palestine tragedy."—Michael Sells, John Henry Barrows Professor of Islamic History and Literature in the Divinity School, The University of Chicago\ \ \ \ \ \ Naomi Shihab Nye"There is never a bad time for compassion. But could there possibly be a better time than now? Adina Hoffman's incredibly well-researched, thoughtful, wise biography of the fascinating Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali might be the kind of project that serves as model for all that might save a region. Someone paying deep and loving attention to someone else—someone listening, not only to his words, but to the details and context of his whole life and the experience of his people. This book is a profoundly humane and tender experience, and should not be missed by anyone who cares about a better future and respect for the past."—Naomi Shihab Nye, author of You and Yours\ \ \ \ \ \ Cerise Press"Informative, captivating and fast-moving, this first biography of the Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali (1933- ) is a true delight to read."—Greta Aart, Cerise Press\ \ \ \ \ Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript LibraryWinner of the 2013 Windham Campbell Prizes administered by the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.\ \ \ \ \ The Barnes & Noble ReviewPoetry is what gets lost in translation -- and also what slips through the historian's net. The attention of a biographer, after all, tends to be fixed on the facts of a poet's life, rather than on the form of his line. That much I remember from learning to read in the old literary school called New Criticism, which insisted that the meaning of a poem was the poem itself. And for the most part those strictures still ring true. \ But the contemporary Palestinian author Taha Muhammad Ali has been wonderfully served by his translators, so that his works in English still have what someone once identified as the defining effect of great poetry, which is to make the hair on the back of your neck stand up. Now, with Adina Hoffman's My Happiness Bears No Relation to Happiness: A Poet's Life in the Palestinian Century, we have a book that enriches the appreciation of his work, rather than using it as an occasion for political commentary on the Middle East. (Not so coincidentally, the poet's biographer is married to Peter Cole, one of the translators of Ali's So What: New and Selected Poems, 1971-2005.)\ Born in 1931, Ali was among the refugees when Israel was formed in 1948. His village, called Saffuriyya, was depopulated following air strikes by the new state's military. The villagers scattered, with Ali himself ending up in Lebanon for a while before he managed to sneak back into his homeland. The ambition to write formed in adolescence, well before the events known in Arabic as al-Nakba (the Catastrophe). But his formal education was limited, and the talent for fiction and poetry took a long time to ripen, while Ali's other gift seems to have asserted itself very early on. He had a knack for finding a niche as a small merchant -- whether vending food and drink to day laborers in his village, or peddling odds and ends to pedestrians. Hoffman includes photos of the souvenir shop Ali still runs in Nazareth. While known to the world as an author, Ali remains, as he wrlyly puts it, a Muslim businessman who sells Christian mementos to Jewish tourists.\ Well, it's a living. But adapting to one's circumstances does not necessarily mean accepting them. Much of the power of Ali's work comes from the sense it conveys of having lost a familiar world in a moment of absolute bewilderment that has never quite abated. In a poem recalling the exodus from his village, he writes:\ We did not weep when we were leaving --\ for we had neither time nor tears,\ and there was no farewell.\ We did not know at the moment of parting that it was a parting,\ so where would our weeping have come from?\ Another poem -- written in the wake of Israel's invasion of Beirut in 1982 -- reflects a spirit of intransigence that runs deeper than any political manifesto can express:\ The street is empty as a monk's memory,\ and faces explode in the flames like acorns --\ and the dead crowd the horizon and doorways.\ No vein can bleed more than it already has,\ no scream will rise higher than it's already risen.\ We will not leave!\ Such passages of anger and defiance are rare in Ali's work, however -- and they are complicated by passages in which he refuses to let them take command. Readers who pick up a poem called "Revenge" may find their worst prejudices about "the Arab mind" seemingly confirmed when the speaker expresses his wish to "meet in a duel / the man who killed my father / and razed our home / expelling me / into / a narrow country." One or the other of them must end up dead.\ But then the poet begins to imagine the family and friends of his enemy -- or the agony of his isolation, perhaps, if the man is alone in the world. The speaker of the poem abandons the thought of avenging an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. Instead, he finds a different way to retaliate:\ I'd be content to ignore him when I passed him by on the street -- as I convinced myself that paying him no attention in itself was a kind of revenge.\ As his biographer notes, this unexpected variation on the theme of "turning the other cheek" makes this "among the most effective of Taha's poems," especially in public performances. Hoffman describes a reading Ali gave to an all-Jewish audience in Israel, after which he was approached by "a middle-aged woman in sensible sandals and a sun hat" who said she found the poem beautiful. "You know, the Jews felt the same way for many years," she told him, then leaned in to confess: "But I'm sorry to tell you, it doesn't work!"\ As a young writer-in-training, Ali painstakingly taught himself the fine points of Arabic grammar and cultural history, and also immersed himself in English. He worked his way through a second-hand copy of An Approach to Literature -- the classic New Critical textbook from 1936 by Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren, who taught readers to appreciate irony and paradox. Clearly he learned their lessons well. Like many Arab writers of his generation, he kept up with translations of Soviet literature, and I suspect Hoffman could have probed deeper into the possible influence of Vladmir Mayakovsky and Yevgeny Yevtushenko.\ He also read the work of his peers, who in the 1960s created an overtly political "resistance literature" (as an influential critic termed it) with mass appeal. By contrast, Ali's work tends to be quieter and less declamatory. His verse is "jagged and personal," as Hoffman aptly characterizes it, with "a dark sense of humor and oddly syncopated rhythms"; it does not sound like either protest poetry or "the dreamy romanticism that usually served as an alternative." It embodies what one classical Arabic literary term sums up as "a difficult, elusive, or even inscrutable simplicity."\ So, in its way, does Ali's life -- with its modest routines in the souvenir shop covering over an agonizing history of displacement, of being made a foreigner in the land of his own birth. Thanks to Adina Hoffman's biography, readers are now better able to appreciate his struggle to create literature in circumstances that might otherwise yield only despair. --Scott McLemee\ Scott McLemee writes the weekly column "Intellectual Affairs" for Inside Higher Ed. He is a member of the board of directors of the National Book Critics Circle.\ \ \