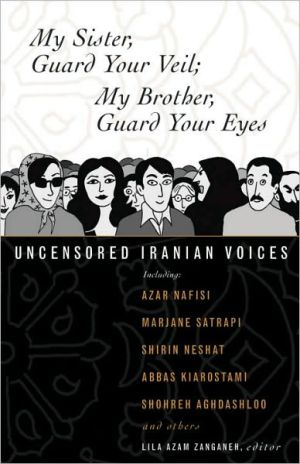

My Sister, Guard Your Veil; My Brother, Guard Your Eyes: Uncensored Iranian Voices

In the first anthology of its kind, Lila Azam Zanganeh argues that although Iran looms large in the American imagination, it is grossly misunderstood-seen either as the third pillar of Bush's infamous "axis of evil" or as a nation teeming with youths clamoring for revolution.\ This collection showcases the real scope and complexity of Iran through the work of a stellar group of contributors-including Azar Nafisi and with original art by Marjane Satrapi. Their collective goal is to counter the...

Search in google:

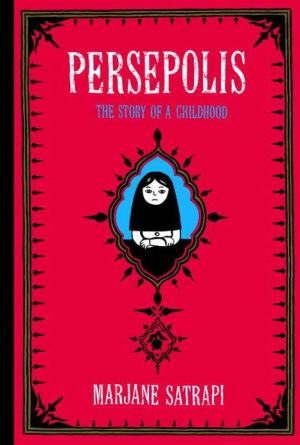

In the first anthology of its kind, Lila Azam Zanganeh argues that although Iran looms large in the American imagination, it is grossly misunderstood—seen either as the third pillar of Bush’s infamous “axis of evil” or as a nation teeming with youths clamoring for revolution.This collection showcases the real scope and complexity of Iran through the work of a stellar group of contributors—including Azar Nafisi and with original art by Marjane Satrapi. Their collective goal is to counter the many existing cultural and political clichés about Iran. Some of the pieces concern feminism, sexuality, or eroticism under the Islamic Republic; others are unorthodox political testimonies or about race and religion. Almost all these contributors have broken artistic and cultural taboos in their work.Journalist Reza Aslan, author of No God But God, explains why Iran is not a theocracy but, rather, a “mullahcracy.” Mehrangiz Kar, a lawyer and human rights activist who was jailed in Iran and is currently a fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, argues that the Iranian Revolution actually engendered the birth of feminism in Iran. Journalist Azadeh Moaveni reveals the underground parties and sex culture in Tehran, while Gelareh Asayesh, author of Saffron Sky, writes poignantly on why Iranians are not considered white in America, even though they think they are. Poet and writer Naghmeh Zarbafian expounds on the surreal experience of reading censored books in Iran, while Roya Hakakian, author of Journey from the Land of No: A Girlhood Caught in Revolutionary Iran, recalls the happy days of Iranian Jews. With a sharp, incisive introduction by Lila Azam Zanganeh, this diverse collection will alter what you thought you knew about Iran. Publishers Weekly This timely little book offers a thoughtful, wide-ranging and captivating introduction to a dynamic country most Americans still regrettably associate with romantic-exotic or religious-fanatical stereotypes. Centering on questions of identity and subjectivity in and outside Iran's Islamic Republic, the 15 prominent indigenous and ex-pat voices showcased in this collection include bestselling authors Azar Nafisi (Reading Lolita in Tehran), Azadeh Moaveni (Lipstick Jihad) and Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis), as well as renowned filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, Oscar-nominated actress Shoreh Aghdashloo (House of Sand and Fog) and acclaimed visual artist Shirin Neshat. The brief, often breezy essays, reminiscences, reportage and interviews overturn the facile image of Iran as a single, homogenous entity, providing animated discussions of politics, sex, art, women's rights, racism, poetic culture, underground nightlife, Tehran's Jewish community, censorship, economic inequality and cross-cultural (mis)understanding under a regime that is highly oppressive but continually subverted. Arranged and framed with care by editor Zanganeh (and featuring original art by Satrapi), the book's contents resist an overarching, dogmatic point of view, presenting instead an open-ended invitation to dialogue. Readers will find this volume complex but accessible; it reveals the human stories behind the veil of the headlines. (Apr.) Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.

\ \ My Sister, Guard Your Veil; My Brother, Guard Your Eyes\ \ \ UNCENSORED IRANIAN VOICES\ \ \ \ Beacon Press\ \ \ Copyright © 2006\ \ Lila Azam Zanganeh\ All right reserved.\ \ ISBN: 0-8070-0463-4\ \ \ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ THE STUFF THAT DREAMS\ ARE MADE OF\ Azar Nafisi\ The story I want to tell begins at the Tehran airport, decades ago,\ when at the age of thirteen I was sent away to England to pursue\ my education. Most friends and relatives who were there on that\ day will remember that I was very much the spoiled brat, running\ around the Tehran airport, crying I didn't want to leave.\ From the moment I was finally captured and placed on the airplane,\ from the moment the doors were closed on me, the idea\ of return, of home, of Iran became a constant obsession that colored\ almost all my waking hours and my dreams. This was my\ first concrete lesson in the transience and infidelities of life. The\ only way I could retrieve my lost and elusive Tehran was through\ my memories and a few books of poetry I had brought with me\ from home. Throughout the forlorn nights in a damp and gray\ town called Lancaster, I would creep under the bedcovers, with\ a hot water bottle to keep me warm, while I opened at random\ three books I kept by my bedside: Hafiz, Rumi, and a modern\ female Persian poet, Forugh Farrokhzad. I would read well into\ the night, a habit I have not given up, going to sleep asthe words\ wrapped themselves around me like aromas from an old spice\ shop, resurrecting my lost but unforgotten Tehran.\ I did not know then that I was already creating a new home,\ a portable world that no one would ever have the power to take\ away from me. And I adapted to my new home through reading\ and revisiting Dickens, Austen, Brontë, and Shakespeare, whom\ I had met with a thrill of sheer delight on the very first day of\ school. Later, of course, I would begin to discover America\ through the same imaginative sorcery-the writing of F. Scott\ Fitzgerald, Saul Bellow, Mark Twain, Henry James, Philip Roth,\ Emily Dickinson, William Carlos Williams, and Ralph Ellison.\ Yet for decades, whether in England or America, my existence\ was defined by the idea of return. I imposed my lost Iran on all\ the moments of my life-even transferring to New Mexico for\ a semester mainly because its mountains and the shaded colors of\ its star-filled nights reminded me of my Iran. Late in the summer\ of 1979, two days after I completed the defense of my dissertation,\ I was on a plane, first to Paris, then to Tehran.\ But as soon as I landed in the Tehran airport, I knew, irrevocably,\ that home was no longer home. And it is apt, I presume,\ that home should never feel too much like home-that is, too\ comfortable or too smug. I always remember Adorno's claim that\ the "Highest form of morality is to not feel at home in one's own\ home." So for spurring me to pose myself as a question mark, for\ altering my sense of home, as for so many other things, I should\ be grateful to the Islamic Republic of Iran.\ There was also another sense in which home was no longer\ home, not so much because it destabilized and impelled me to\ search for new definitions, but mainly because it forced its own\ definitions upon me, thus turning me into an alien entity. A new\ regime had established itself in the name of my country, my religion,\ and my traditions, claiming that the way I looked and\ acted, what I believed in and desired as a human being, a woman,\ a writer, and a teacher were essentially alien and did not belong\ to this home.\ In the fall of 1979, I was teaching Huckleberry Finn and The\ Great Gatsby in spacious classrooms on the second floor of the\ University of Tehran, without actually realizing the extraordinary\ irony of our situation: in the yard below, Islamist and leftist\ students were shouting "Death to America," and a few streets\ away, the U.S. embassy was under siege by a group of students\ claiming to "follow the path of the imam." Their imam was\ Khomeini, and he had waged a war on behalf of Islam against the\ heathen West and its myriad internal agents. This was not purely\ a religious war. The fundamentalism he preached was based on\ the radical Western ideologies of communism and fascism as\ much as it was on religion. Nor were his targets merely political;\ with the support of leftist radicals he led a bloody crusade against\ Western "imperialism": women's and minorities' rights, cultural\ and individual freedoms. This time, I realized, I had lost my connection\ to that other home, the America I had learned about in\ Henry James, Richard Wright, William Faulkner, and Eudora\ Welty.\ In Tehran, the first step the new regime took before implementing\ a new constitution was to repeal the Family Protection\ Law which, since 1967, had helped women work outside the\ home and provided them with substantial rights in their marriage.\ In its place, the traditional Islamic law, the Sharia, would\ apply. In one swoop the new rulers had set Iran back nearly a century.\ Under the new system, the age of marital consent for girls\ was altered from eighteen to nine. Polygamy was made legal as\ well as temporary marriages, in which one man could marry as\ many women as he desired by contract, renting them from five\ minutes to ninety-nine years. What they named adultery and\ prostitution became punishable by stoning.\ Ayatollah Khomeini justified these actions by claiming that\ he was in fact restoring women's dignity and rescuing them from\ the degrading and diabolical ideas that had been thrust upon\ them by Western imperialists and their agents, who had conspired\ for decades to destroy Iranian culture and traditions.\ In formulating this claim, the Islamic regime not only robbed\ the Iranian people of their rights, it robbed them of their history.\ For the true story of modernization in Iran is not that of an outside\ force imposing alien ideas or-as some opponents of the\ Islamic regime contend-that of a benevolent shah bestowing\ rights upon his citizens. From the middle of the nineteenth century,\ Iran had begun a process of self-questioning and transformation\ that shook the foundations of both political and religious\ despotism. In this movement for change, many sectors of the\ population-intellectuals, minorities, clerics, ordinary people,\ and enlightened women-actively participated, leading to what\ is known as the 1906 Constitutional Revolution and the effective\ implementation of a new constitution based on the Belgian\ model. Women's courageous struggles for their rights in Iran\ became the most obvious manifestation of this transformation.\ Morgan Shuster, an American who had lived in Iran, even stated\ in his 1912 book, The Strangling of Persia: "The Persian women\ since 1907 had become almost at a bound the most progressive,\ not to say the most radical, in the world. That this statement upsets\ the ideas of centuries makes no difference. It is the fact."\ By 1979, at the time of the revolution, women were active in\ all areas of life in Iran. The number of girls attending schools was\ on the rise. The number of female candidates for universities had\ increased sevenfold during the first half of the 1970s. Women\ were encouraged to participate in areas previously closed to them\ through a quota system that offered preferential treatment to\ eligible girls. Women were scholars, police officers, judges, pilots,\ and engineers-present in every field except the clergy. In\ 1978, 333 out of 1,660 candidates for local councils were women.\ Twenty-two were elected to the Parliament, two to the Senate.\ There was one female Cabinet minister, three sub-Cabinet undersecretaries\ (including the second-highest ranking officials in\ both the Ministry of Labor and Mines and the Ministry of Industries),\ one governor, one ambassador, and five mayors.\ After the demise of the shah, many women, in denouncing\ the previous regime, did so demanding more rights, not less.\ They were advanced enough to seek a more democratic form of\ governance with rights to political participation. From the very\ start, when the Islamists attempted to impose their laws against\ women, there were massive demonstrations, with hundreds of\ thousands of women pouring into the streets of Tehran protesting\ against the new laws. When Khomeini announced the imposition\ of the veil, there were protests in which women took to\ the streets with the slogans: "Freedom is neither Eastern nor\ Western; it is global" and "Down with the reactionaries! Tyranny\ in any form is condemned!" Soon the protests spread, leading to\ a memorable demonstration in front of the Ministry of Justice,\ in which an eight-point manifesto was issued. Among other\ things, the manifesto called for gender equality in all domains of\ public and private life as well as for the guarantee of fundamental\ freedoms for both men and women. It also demanded that\ "the decision over women's clothing, which is determined by\ custom and the exigencies of geographical location, be left to\ women."\ Women were attacked by the Islamic vigilantes with knives\ and scissors, and acid was thrown in their faces. Yet they did not\ surrender, and it was the regime that retreated for a short while.\ Later, of course, it made the veil mandatory, first in workplaces,\ then in shops, and finally in the entire public sphere. In order to\ implement its new laws, the regime devised special vice squads,\ called the Blood of God, which patrolled the streets of Tehran\ and other cities on the lookout for any citizen guilty of "moral\ offense." The guards could raid shopping malls, various public\ spaces, and even private homes in search of music or videos, alcoholic\ drinks, sexually mixed parties, and unveiled or improperly\ veiled women.\ The mandatory veil was an attempt to force social uniformity\ through an assault on individual and religious freedoms, not an\ act of respect for traditions and culture. By imposing one interpretation\ of religion upon all its citizens, the Islamic regime deprived\ them of the freedom to worship their God in the manner\ they deemed appropriate. Many women who wore the veil, like\ my own grandmother, had done so because of their religious beliefs;\ many who had chosen not to wear the veil but considered\ themselves Muslims, like my mother, were now branded as infidels.\ The veil no longer represented religion but the state: not\ only were atheists, Christians, Jews, Baha'is, and peoples of other\ faiths deprived of their rights, so were the Muslims, who now\ viewed the veil more as a political symbol than a religious expression\ of faith. Other freedoms were gradually curtailed: the\ assault on the freedom of the press was accompanied by censorship\ of books-including the works of some of the most popular\ classical and modern Iranian poets and writers-a ban on\ dancing, female singers, most genres of music, films, and other\ artistic forms, and systematic attacks against the intellectuals and\ academics who protested the new means of oppression.\ In a Russian adaptation of Hamlet distributed in Iran, Ophelia\ was cut out from most of her scenes; in Sir Laurence Olivier's\ Othello, Desdemona was censored from the greater part of the\ film and Othello's suicide was also deleted because, the censors\ reasoned, suicide would depress and demoralize the masses. Apparently,\ the masses in Iran were quite a strange lot, since they\ might be far more demoralized by witnessing the death of an\ imaginary character onscreen than being themselves flogged and\ stoned to death ... Female students were reprimanded in schools\ for laughing out loud or running on the school grounds, for\ wearing colored shoelaces or friendship bracelets; in the cartoon\ Popeye, Olive Oyl was edited out of nearly every scene because\ the relationship between the two characters was illicit.\ The result was that ordinary Iranian citizens, both men and\ women, inevitably began to feel the presence and intervention of\ the state in their most private daily affairs. The state did not\ merely punish criminals who threatened the lives and safety of\ the populace; it was there to control the people, to flog and jail\ them for wearing nail polish, Reebok shoes, or lipstick; it was\ there to watch over young girls and boys appearing in public. In\ short, what was attacked and confiscated were the individual and\ civil rights of the Iranian people.\ Ayatollah Khomeini's fatwa against Salman Rushdie years\ later did not represent a divide between Islam and the West, as\ some claimed. It was a reaction to the dangers posed by a thriving\ individual imagination on totalitarian mindsets, which cannot\ tolerate any form of irony, ambiguity, and irreverence. As\ Carlos Fuentes stated, the ayatollah had issued a fatwa not just\ against a writer but also against the democratic form of the novel,\ which frames a multiplicity of voices-from different and at\ times opposing perspectives-in a critical exchange where one\ voice does not destroy and eliminate another. What more dangerous\ subversion than this democracy of voices? And in that\ sense, America's extraordinary literary heritage kept reminding\ me, throughout those years, how heavily genuine democracy depends\ on what we might call a democratic imagination.\ But according to the "guardians of morality" in the Islamic\ Republic, books such as Lolita or Madame Bovary were morally\ corrupt; they set wretched examples for the readers, motivating\ them to commit immoral acts. Like all totalitarians, they could\ not differentiate between reality and imagination, so they attempted\ to impose their own version of truth upon both life and\ fiction. Yet we do not read Lolita to learn more about pedophilia,\ in the same way that we do not immediately decide to live up in\ the trees after reading Calvino's Baron in the Tree. We do not read\ in order to turn great works of fiction into simplistic replicas of\ our own realities, we read for the pure, sensual, and unadulterated\ pleasure of reading. And if we do so, our reward is the discovery\ of the many hidden layers within these works that do not\ merely reflect reality but reveal a spectrum of truths, thus intrinsically\ going against the grain of totalitarian mindsets.\ Quite to the contrary, the ruling elite in Iran imposed the\ figments of its own imagination upon our lives, our reality. My\ students could never taste the ordinary pleasures of life-what\ one of them, Yassi, called the blacklisted details that are so readily\ available to others-such as the caress of the sun on their skin\ or the wind in their hair. The simple act of leaving the house\ every day became a tortuous and guilty lie, because we had to\ dress ourselves in the mandatory veil and be transformed into the\ alien image the state had carved for us.\ In order to escape and negate the alien image-this mandatory\ lie that began with our appearances and permeated all aspects\ of our lives-we needed to re-create ourselves and rescue\ our confiscated identities. To restore our identities, we had to\ resist the oppressor through our own creative resources. And we\ had to do this by refusing to choose the same language as our oppressors.\ Resistance in Iran had come to mean nonviolent confrontation,\ both through political demands and through a refusal\ to comply, an insistence upon the individual's own sense of integrity:\ demanding respect and recognition whoever we were\ and refusing to become the figments the regime wished to turn\ us into.\ Inexorably, the same rules that had been fashioned to keep the\ citizens leashed became, over the course of time, weapons with\ which Iranians demonstrated their dissent. Because the revolution\ had turned the streets of Tehran and other cities into cultural\ war zones, in which agents of the state were searching and\ punishing citizens not for guns and grenades but for other, far\ more deadly weapons-a strand of hair, a colored ribbon, trendy\ sunglasses-the regime had politicized not only a dissident elite\ but every Iranian individual as well. We were energized, not so\ much because we were innately political but, rather, in order to\ preserve our sense of individual integrity as women, writers, and\ academics-in a word, as ordinary citizens who wished to live\ their lives.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from My Sister, Guard Your Veil; My Brother, Guard Your Eyes\ \ Copyright © 2006 by Lila Azam Zanganeh.\ Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.\ \

The stuff that dreams are made of1I grew up thinking I was white12How can one be Persian?20From here to mullahcracy24Death of a mannequin30The last chapter in the book of Exodus38Women without men44Sex in the time of mullahs55Misreading Kundera in Tehran62Receding worlds74A taste of my cinema81An alley greener than the dream of God96Don't cry for me, America104Why acting set me free112Tehran underground119

\ Publishers WeeklyThis timely little book offers a thoughtful, wide-ranging and captivating introduction to a dynamic country most Americans still regrettably associate with romantic-exotic or religious-fanatical stereotypes. Centering on questions of identity and subjectivity in and outside Iran's Islamic Republic, the 15 prominent indigenous and ex-pat voices showcased in this collection include bestselling authors Azar Nafisi (Reading Lolita in Tehran), Azadeh Moaveni (Lipstick Jihad) and Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis), as well as renowned filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, Oscar-nominated actress Shoreh Aghdashloo (House of Sand and Fog) and acclaimed visual artist Shirin Neshat. The brief, often breezy essays, reminiscences, reportage and interviews overturn the facile image of Iran as a single, homogenous entity, providing animated discussions of politics, sex, art, women's rights, racism, poetic culture, underground nightlife, Tehran's Jewish community, censorship, economic inequality and cross-cultural (mis)understanding under a regime that is highly oppressive but continually subverted. Arranged and framed with care by editor Zanganeh (and featuring original art by Satrapi), the book's contents resist an overarching, dogmatic point of view, presenting instead an open-ended invitation to dialogue. Readers will find this volume complex but accessible; it reveals the human stories behind the veil of the headlines. (Apr.) Copyright 2006 Reed Business Information.\ \