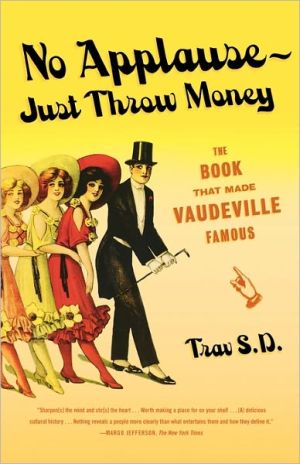

No Applause--Just Throw Money: The Book That Made Vaudeville Famous

A seriously funny look at the roots of American Entertainment\ When Groucho Marx and Charlie Chaplin were born, variety entertainment had been going on for decades in America, and like Harry Houdini, Milton Berle, Mae West, and countless others, these performers got their start on the vaudeville stage. From 1881 to 1932, vaudeville was at the heart of show business in the States. Its stars were America's first stars in the modern sense, and it utterly dominated American popular culture....

Search in google:

A seriously funny look at the roots of American EntertainmentWhen Groucho Marx and Charlie Chaplin were born, variety entertainment had been going on for decades in America, and like Harry Houdini, Milton Berle, Mae West, and countless others, these performers got their start on the vaudeville stage. From 1881 to 1932, vaudeville was at the heart of show business in the States. Its stars were America's first stars in the modern sense, and it utterly dominated American popular culture. Writer and modern-day vaudevillian Trav S.D. chronicles vaudeville's far-reaching impact in No Applause—Just Throw Money. He explores the many ways in which vaudeville's story is the story of show business in America and documents the rich history and cultural legacy of our country's only purely indigenous theatrical form, including its influence on everything from USO shows to Ed Sullivan to The Muppet Show and The Gong Show. More than a quaint historical curiosity, vaudeville is thriving today, and Trav S.D. pulls back the curtain on the vibrant subculture that exists across the United States—a vast grassroots network of fire-eaters, human blockheads, burlesque performers, and bad comics intent on taking vaudeville into its second century.

No Applause - Just Throw Money\ 1WHO PUT THE "DEVIL" IN VAUDEVILLE?While the vaudevillian, as we commonly think of him, did not take the stage until the late nineteenth century, he carried with him a couple of dozen centuries' worth of baggage. To truly appreciate the revolutionary nature of his performance it behooves us to look at the long, hard road that led him there. And so we begin our journey with a detour—back ... back ... through the murky mists of time ... back to the very dawn of creation ... back to the first act of nonconformity by any sentient being ... \ \ Old Scratch was the first hoofer.Milton depicts the universe's first slapstick moment in Paradise Lost. Not long after the world's creation, Satan took a wicked pratfall, tumbling earthward out of his privileged digs in the celestial vault, compelling him to toil thereafter amongst all sorts of lame clowns who were made (like him) all too imperfectly in God's image. Mae West said it best: "I'm No Angel."Despite numerous tragic attempts to create a utopia in our midst, mankind in its weakness finds itself perennially veering from the high road to the trough of low amusements. Historically, that ditch has been a pretty crowded place, full of strange and unlikely company: on the one hand, clowns, jugglers, singers of sweet love songs, and others of their ilk; on the other, tavern-keepers, card sharks, prostitutes, and their brother(and sister) criminals. From the beginning of the Christian era until quite recently, these two groups have always gone hand in hoof: Entertainment and Evil, a double act spawned in the mind of a maniac. Entertainment feeds us punch lines; Evil, with his slow burn, is the straight man. And the dirty-minded maniac? Let's just call him "Reverend."Ludicrous though it may seem to us to place jugglers, singers, and dancers in a caste with "Gypsies, Tramps, and Thieves," Christians (first Catholics and then Protestants) have done so for centuries. For moral support they need look no further than Saint Paul, who in his Epistle to the Ephesians (5:3—4) lumps "foolish talking" and "jesting" in with fornication, uncleanness, and covetousness. In his Epistle to the Galatians (5:21), "revellings" are in a class with "envyings," "murders," and "drunkenness." It is a litmus test that would sully the reputation of an Osmond.To us, for whom Marilyn Manson is old hat, and who undoubtedly know at least one grandparent who can sing all the words to "Sympathy for the Devil," this is madness. Yet underneath the madness—at least initially—lay a method.Theatrical performers, consciously or no, practice an art that began as a rite to honor the Greek god Dionysus, a deity principally associated with sexual abandon and intoxication. Aspects of the ceremony—even well after it had evolved into what we now call theater—were by most measures "obscene."The shadow of Dionysus still darkens our fragmentary memories of antiquity. Thanks largely to the cinema's depictions of life under various caesars, the ancient world retains a distorted Bacchic patina. Say "Rome," and images out of Caligula and Fellini's Satyricon rage through the brain: public baths full of immodest sculptures, patronized by men, women, children, and livestock. Great, fat, oily courtiers in togas recline on silk couches munching pornographic pastries. Frolicking nymphs with grape leaves in their hair play leapfrog in the forest, pausing only to indulge their twin tastes in human sacrifice and lesbianism. Satyrs in outlandish codpieces swing their phalluses at one another, eventually coalescing into a great, heaving, perfumed, peach-colored daisy chain.The early leaders of the Catholic Church apparently thought such images so horrible they couldn't stop thinking about them.Come to think of it, neither can I.Worldliness, materialism, sex, pleasure—all nicely integrated into the philosophies of the ancients—were now tarred with the broad brush of "evil." To turn the pagan Europeans from their wicked ways, some scholars feel that Dionysus was purposely equated with "Satan."In decorative art and statuary, Dionysus and his cohorts (such as the demigod Pan) had been depicted as goatlike, possessing horns, hooves, and a tail, uncannily resembling what we now think of as the devil. Yet no such description of Satan exists in the Bible. There he is depicted only as a fallen angel, a serpent, or something called Leviathan. How astute (not to mention diabolical) of the Church Fathers to associate the nature-worship of Europe's oldest traditions with Evil Incarnate.Fourteen or more centuries of official persecution of variety entertainers only make sense in this context—they have their roots in pagan antiquity. Among the first recorded variety performers were the Greek mimes, a motley lot who lumbered out of southern Italy during Greece's Golden Age to juggle, perform acrobatics, dance, and perform comical sketches for the vastly more dignified Athenians. These were very different from our modern mimes, in their whiteface and berets, who walk against the wind and scream-in-an-ever-shrinking-box (those mimes are satanic).Rome, too, had its mimes; they begin to materialize in the Republic at about 300 B.C. Roman mimes were closely associated with the Atellan farce, ancestor to the Roman comedies of Plautus and Terence, the commedia dell'arte, the comic creations of Shakespeare and Molière, and all slapstick straight through the vaudeville era. The fabula raciniata was a form of early variety that incorporated tightrope walkers, trapeze artists, tumblers, jugglers, sword-swallowers, fire-eaters, dancers, operatic singers, and stilt-walkers. Tony Curtis proudly proclaimed himself among this performing clique in the 1960 film Spartacus: "I yam a magician and seengah of sawngs," he announces in ancient Brooklynese.Throughout Euro-American history, the descendants of those mimes persisted. During the Middle Ages, itinerant bands of jongleurs, minstrels, troubadours, and similar entertainers would tramp from village to village with their exhibitions of juggling, fire-eating, magic tricks, little songs, and bits of clowning. In Elizabethan England, they came in from the cold and were incorporated into the presentation of great works of dramatic literatureas preludes and entr'actes. That tradition was perpetuated in America into the late nineteenth century, when, as one historian put it, "all shows were variety shows."Yet despite their deathless popularity in every land they roamed, these proto-vaudevillians always found public officials rabid to ring down the curtain."The condition of faith and the laws of Christian discipline forbid among other sins of the world the pleasures of the public shows," wrote Tertullian, a theologian of the second century A.D.With a pitch like that, it's a wonder he made any converts at all. Yet the animus against pagan-derived spectacle by the early followers of Christ is understandable: some of those spectacles had involved the consumption of Christians by the creatures we in the business call "big cats." Siegfried and Roy meet The Faces of Death as staged by Cecil B. DeMille. A "light show" mounted by Nero might consist of hundreds of Christians tied to stakes, coated with tar and set afire. In the Atellan farce an unfortunate Christian named Laureolus is recorded to have been crucified during the show's climax and subsequently torn apart by wild animals. I repeat: this is in a farce. Not in a league with ritual murder, perhaps, but plenty appalling, was the attendant practice of presenting live sex acts as spectacle. In the case of slaves, many of whom were Christian, such performances would have been quite involuntary, and (for some, no doubt) a fate worse than death.To enter another dangerous arena, drag, or female impersonation, has been a staple of theater since ancient times. This, too, had been a specialty of the Roman mimes, and one imagines a full range of possible transvestisms, from the silly and vulgar buffoonery associated with Milton Berle, all the way to the sort of feminine role-playing that takes place in maximum-security prisons. Ultimately, any lasting bad rep attached to drag would come from both kinds. Neither the shameless fool nor the sexual "deviant" had any place in the Christian order. By the early twentieth century, the feminine artistry of biological males like Julian Eltinge, Bert Savoy, Karyl Norman, and dozens of others would grace even the most conservative stages of America and Europe with little public furor. But they had a long road to walk (in high heels, no less) before they reached that coveted stage.Fresh from the outrages of Rome, the rancor of early Church Fatherstoward the theater is not surprising. But what of the lesser indictments that have haunted performers throughout history until the eve of our own era? What about the claims that the theater is a mere cesspool, a haven for prostitutes, con men, thieves, Satanists, ruffians, and drunkards?"The participants of show business," wrote columnist Earl Wilson, "are rumpots, nymphomaniacs, prostitutes, fakes, liars, cheaters, pimps, hopheads, forgers, sodomists, slobs, absconders—but halt. I understate it horribly."As late as 1904, clergyman J. M. Judy wrote in his treatise Questionable Amusements and Worthy Substitutes:With drunkenness, gambling and dancing, theater-going dates from the beginning of history, and with these it is not only questionable in morals, but it is positively bad ... There you find the man ... who has lost all love for his home, the careless, the profane, the spendthrift, the drunkard, and the lowest prostitute of the street.The startling fact that emerges from these blanket pronouncements is not the extremity of the views; on the contrary, their assessments are right on the button."Cluck, cluck, surely this is an exaggeration," we sophisticated moderns are wont to respond. We laugh off such hyperbolic broadsides as the ravings of a lunatic. We hold this view because the past century has been a time of rehabilitation for the traveling player, not because the charges were ever discredited.Tempting though it may be to scoff at the bugaboos of less enlightened times, these claims (despite their hysterical and intolerant tone) turn out to have been essentially true. Like Vivie in the Shaw play Mrs. Warren's Profession, vaudeville turns out to be the respectable, bourgeois daughter of a common whore. More accurately, a dynasty of whores stretching back to the Queen of Sheba. The only question has ever been: Do you have a problem with whores? Throughout most of human history, ladies (and gentlemen) of the evening have been a featured amenity at nearly all theaters. In Rome, the world's oldest profession had developed into a fine art. There are three dozen words in Latin for as many types of prostitute. Four of them(cymbal players, singing girls, harpists, and mimes) have names that also qualify them for the Roman equivalent of the vaudeville stage. The Roman circuses and amphitheaters were handily equipped with special little enclaves called fornices where men could visit a sex worker during intermission. They were sort of like a concession stand, or those guys at the ball games ("Get yer red hots! Get 'em while they're red, get 'em while they're hot! And when we say hot, we mean hot!"). In medieval times, jongleuresses and lady minstrels entertained the populace, but also doubled as damsels-for-hire. Edward II himself was entertained by several of these charmers, who, with names like "Pearl-in-the-Egg" and "Maude Makejoy," were doubtless fingering more than lute frets.1According to British historian Fergus Linnane's book London: The Wicked City, Elizabethan theaters were patrolled by girls called "orange sellers," who sold oranges, and were only too glad to peel it off. The Restoration stage gave us the actress-courtesan who accepted lavish gifts, jewels, dresses, an apartment—a living, basically—in exchange for being some admirer's girlfriend. One of the most famous actresses of the age, Nell Gwynn, even became the consort to Charles II. That this should be so is not surprising. Surely it's not nuclear physics to conclude that some of the men in the audience, inflamed by the beauties on stage, hearts thumping, minds racing, would fall all over themselves in a mad scramble back to the dressing room with boxes of chocolates, bundles of roses, bottles of champagne, wallets full of cash, family heirlooms, and probably deeds to property, in order to quiet the howling, libidinous demons inside them. Don't ask me why. I guess that's just how God made us.Whether or not an actress was actually a prostitute was immaterial. By the late nineteenth century virtually none of them were, but the association remained. This is due to a peculiar phenomenon that still rears its ugly head, what specialists in rape law call "blaming the victim." Because the woman inspires lustful thoughts in a man (whether she purposes to do so or not) she becomes the source of evil. It's rather like the wolf blaming the sheep for looking delicious. So we find women becoming the Daughters of Eve, the Whores of Babylon, the Jezebels, the Delilahsand Salomes. To parade themselves in front of an audience is a brazen act of provocation inspired by Satan himself. Yet, as we shall see, at vaudeville's peak, in the first decade of the twentieth century, Salome would be very much in demand.Esmerelda in Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre Dame is the archetype of the nascent medieval variety artist: she dances, plays a tambourine, tells jokes, and performs a routine with a trained goat. That dance—that Middle Eastern, sexy Gypsy dance—proves the character's undoing. Ecstatic or "primitive" dancing in medieval and Reformation times was associated with witchcraft because it was believed that the dancer bewitched the male spectator by arousing impure thoughts. The anonymous pamphlet A Pleasant Treatise of Witches (1673) describes such a dance as "diabolical ... they take one another by the arms and raise each other from the ground, then shake their heads to and fro like Anticks, and turn themselves as if they were mad." Hanging, stoning, burning, and drowning were the penalties for such behavior. But in the twentieth century, vaudeville dancers would teach America to shimmy, shake, cakewalk, and Toddle the Tolado.Similarly reviled were the minstrels, or professional singers of secular love songs. In the Middle Ages, minstrels were particularly execrated by religious authorities, for they went about filling people's heads with seductive thoughts. As the medieval mystic Mechtild of Magdeburg wrote: "The miserable minstrel who with pride can arouse sinful vanity / weeps more tears in hell than there is water in the sea."To bring the matter closer to home, think of most of the famous singers of the past century. Is there any doubt that the vast majority of them have made more than their fair share of "conquests"? Sinatra, Elvis, and the Beatles amongst them must have dispatched over a thousand women, plenty of them teenagers, most of them one-night stands, all of them somebody's daughter. This wasn't invented yesterday. The guy with the guitar always gets the chicks, even when the guitar is a mandolin and the love song is "Greensleeves."One of these strolling Lotharios is most germane to our story, for (as tradition has it) he gave vaudeville its name. Some say the word is a corruption of val de vire, or vau de vire, meaning the valley of the Vire River, which is in Normandy, where a troubadour named Olivier Basselin made certain drinking songs popular in the fifteenth century. Thus wasvaudeville, like the theater itself, born in a bottle. Imagine the setting: a wayside inn full of drunken, dirty peasants, Falstaff, Nym, and Pistol, feeling up the wenches and making lewd jokes. This would be the variety-arts setting for at least the next three centuries. But while the word "vaudeville" was coined in the Middle Ages, there will be much water (and more alcohol) under the bridge before we arrive at the unlikely destination known as American vaudeville.Efforts to keep sex off the stage could sometimes backfire. The medieval English had banned women from the stage for fear of encouraging indecent displays. The female roles were all played by young boys in girlish costume. The result was that by Elizabethan times you had the unsettling situation of innocent children playing sensuous female roles like Juliet and Cleopatra, their hair long, their cheeks rouged, and their little eyelashes batting coquettishly. Ironically, an effort to suppress sexuality resulted in something uncomfortably skirting perversion. In this, perhaps, the Elizabethan theater had something in common with prisons, seminaries, English boarding schools, and the navy. Whether or not suspicions of pederasty had any real foundation, though, they added to the theater's stigmatization in some quarters. In 1629, the poet Francis Lenton labeled boy drag one of the "tempting baits of Hell / Which draw more youth unto the damned cell / Of furious lust." But we'll leave this tangent for the friends and enemies of NAMBLA to debate.As that unregenerate sinner Oscar Wilde taught us, theater is, at bottom, the fine art of lying. Putting on a costume and claiming to be someone entirely different is a form of misrepresentation, or "false witness." As the temptation must have been great for the beautiful actress to capitalize on her advantages, so too must it have been for the artful, shape-shifting actor to cross the line from thespian to confidence man.In medieval times, one sort of traveling entertainer embodied both sides of this wooden nickel. Performing his shows on moveable tables or "benches," the mountebank (literally "mount the bench" in Italian—as in "climb up on this improvised stage") was part businessman, part entertainer, making quack medicine his dodge. But he was also a showman, presenting a variety bill that might include clowning, slack-wire walking, juggling, conjuring, and feats of strength. The show was just bait, however. When the crowd reached critical mass, the mountebankwould proceed with his real agenda: selling medicinal tonics, elixirs, and powders and performing simple medical services, such as corn cutting.The mountebank was the ancestor of the pitchman, the carnival barker, and the circus spieler, not to mention our entire modern model of entertainment programming presented by advertising sponsors. Shakespeare "conjures" an unflattering image of a mountebank in The Comedy of Errors:... one Pinch; a hungry, lean-faced villain; A mere anatomy, a mountebank, A threadbare juggler, and a fortune-teller; A living-dead man. This pernicious slave, Forsooth, took on him as a conjurer; And, gazing in mine eyes, feeling my pulse, And with no face, as 'twere out-facing me, Cries out, I was posses'd.Though such medicine shows (as they came to be known) have their origins in the Middle Ages, they persisted into the twentieth century and have come to be thought of as characteristically American. This is the "snake oil" patent medicine salesman of song and story, once a fact of life in rural America, and most prominently embodied in the character devised by W. C. Fields. Such shows were to coexist with and enrich vaudeville, sending forth such distinguished alumni as Buster Keaton, Harry Langdon, Eubie Blake, Jesse Lasky, Fred Stone, and Harry Houdini.The mountebank was the prototypical theatrical entrepreneur. His brother in charms was the ciarlatano (Italian for "babbler"), whose bag of tricks was a little bigger, embracing not only medical cures, but magic and fortune-telling as well. Gypsies (more properly known as Roma, a people believed to have migrated to Europe from India), became associated with the latter line of work, which remains a staple at fairs, amusement parks, and carnivals to this day. The classic American charlatan is captured in the character of Professor Marvel from the 1939 film version of The Wizard of Oz, with his crystal ball, his turban, and his dubious ability to see into the future.Unfortunately, mountebanks and charlatans have not faired well inthe marketplace of history. Look the words up in the dictionary if you want to know how high their stock is these days. They are held in so little esteem that the terms have lost all theatrical association for the wider public and are now roughly synonymous with "crook." Of course, some of that discredit has been earned. Mediums, astrologers, and doctors with false credentials have been known to perpetrate swindles. These arts seem to fill some awkward middle ground between show business, on the one hand, and science and established religion, on the other. Because of the power wielded by the latter institutions in our society, laws against fortune-telling remain on the books practically everywhere. Yet, in America at least, those laws are rarely enforced, perhaps because life without magic—even pretend magic—is too cruel to contemplate. And just as television shows like Crossing Over and The Psychic Friends Network have held millions in their grip in recent times, vaudeville was rife with mind readers, mentalists, and second-sight artists. A need to believe in them is always there.That didn't stop the authorities in less tolerant times, however, from trying to associate these people with the man downstairs. To make matters worse, the Romany word for "god" is devel, an unfortunate linguistic coincidence that must have led to some misunderstandings worthy of Abbot and Costello. Yet to be fair, the connection between magic and the guy with horns is an old one, and one probably only ever denied under threat of an Inquisitor's thumbscrew.Only recently have magicians, for example, written off their sleight of hand as a question of mere dexterity. Pagan priests were the first magicians, a devious but socially expedient arrangement that may well go back to Neanderthal times. The writings of Egypt, Greece, Rome, Mesopotamia, and the ancient Jews are full of the doings of such characters who kept their flocks in line for fun and profit. Remember your Exodus. When Moses turns his rod into a serpent, what do Pharaoh's priests do? They turn their rods into serpents. When he turns the Nile into blood, what do the priests do? They turn their little bowls of water into "blood." Presto change-o! Miracles, in antiquity, were part of the apparatus of the state, much as a well-rehearsed press conference is today.In the monotheistic order, however, magic, like the art of the actor, became verboten, inside the church and out. Catholicism, for example, relies on the subtler effects produced by music, poetry, wine, and incenseto summon the spirit during its ceremonies—absent are the whistles, shadows, smoke, sparklers, mirrors, and black thread employed by pagan priests to make god appear, whether he wanted to or not. In medieval times, magic and its allied arts (e.g., mind reading, fortune-telling, hypnotism, and ventriloquism) went underground and became a dark cohort of alchemy, necromancy, and all manner of mountebankery. The conical-hatted wizard with stars and moons on his robe emerges from behind the curtain, inspiring Faust, Merlin, Gandalf, and Cookie Jarvis. Echoes of this former devilishness survived in the conjuring field until quite recently. Think of the archetypal magician, with his pointy goatee and mustache, his dark brow, his big, sweeping cape, magic wand, puffs of smoke, flashes of fire, and all of those Kabalistic words that have since become silly to us, but were once meant to call up demons from hell: Hocus Pocus! Ali-kazam! Abracadabra! Yet throughout most of the Christian era, such association with His Satanic Majesty, however great the financial rewards, has meant risking imprisonment, torture, and death at the hands of the authorities. As late as the 1780s, Cagliostro, who'd been the toast of Paris with his illusions, was sentenced to life in prison by the Inquisition; he perished within a year. A little over a century later, the vaudevillian Harry Houdini would escape from dozens of such jails and gain fame and fortune doing it.Yet throughout most of the Christian era, the practitioner of magic needed to keep his bags packed. Another nickname for the Roma people is "Travelers." They lived right in the wagons that were their crucial mode of escape. But the Roma weren't the only travelers. Plenty of others hit the road, too, compelled by nothing more than the perverse imp inside them, that incessant siren song that made the plow and the spinning wheel seem a fate worse than death. Just as in the sideshow world there are many self-made freaks, in the wider performing arts, there are many self-made outsiders. Yet even they to a certain extent were handpicked by fate. Where is there a home for the butter-fingered farm boy who daydreams and drops all his tools? The peasant with an IQ of 160? The village idiot? The queer? The village trollop in a culture where allure was regarded as temptation and thus a hated product of Satan (cursed, as we still say, with a beautiful body)? For such people, the Island of Misfit Toys is the only logical destination.Ironically these nonconformists were trapped in a no-win situation.Forced by circumstances to keep moving, they were then often treated with fear and suspicion for being strangers. They were outsiders by definition, and remained so within living memory. Before the age of broadcasting, travel was the only way a performer could make his living. Once the townspeople have seen your show and tossed their pennies, it's time to move on. Like a farmer rotating his fields, when one area was fallow, you'd have to work another.Yet since the dawn of civilization, civilization has been equated with stability. We like "pillars" of society and good "solid" citizens. We are distrustful of someone who "runs around." The person who comes and goes as he pleases is said to do so "like a thief in the night." Throughout most of Western history, one said "actor" the way one said "hobo." To become an actor was to throw your life away, leave your family (usually with a good deal of rancor), and live on the road. When you consider that Robin Hood, Billy the Kid, Jesse James, Bonnie and Clyde, and John Dillinger were also itinerant and that the definition of "highwayman" is "robber," it's no surprise that traveling performers were lumped in with more nefarious drifters. A 1545 English law expressed this association succinctly, grouping "players" together with "ruffians, vagabonds, masterless men and evil-disposed persons." In the 1940 Walt Disney film Pinocchio the title character is waylaid on the way to school by two evil creatures who teach him to sing "Heigh diddle dee-dee, the actor's life for me." The next thing you know, Pinocchio is smoking cigars and playing pool on Pleasure Island and literally making an ass of himself. Outsiders steal your laundry off the line. They sell you miracle cures that turn out to be turpentine, leaving nothing but a smoldering campfire as a customer-service desk. They entice your children, especially your daughters, down the primrose path. They leave no forwarding address.Vagrancy and vagabondage were therefore serious crimes. In 1572 English law provided that all fencers, exhibitors of trained bears, players, or minstrels not specifically under the patronage of a nobleman be "grievously whipped and burned through the gristle of the right ear with a hot iron of the compass of an inch about." Variations of this law (albeit with diminishing severity) remained on the books until 1824."I must admit that there was some justification for the actor's unsavory social reputation," wrote Groucho Marx. "Most of us stole a little—harmless little things like hotel towels and small rugs. There were a few actors who would swipe anything they could stuff in a trunk." Groucho came from several generations of show folk whose roots were in France and Germany. With little effort one can project such petty thievery among troupers backward across the centuries.A well-known portrait of the American version of these ne'er-dowells is provided by Mark Twain in Huckleberry Finn:DUKE: What's your line—mainly? DAUPHIN: Jour printer by trade; do a little in patent medicines; theater actor—tragedy, you know; take a turn to mesmerism and phrenology when there's a chance; teach singing—geography school for a change; sling a lecture sometimes—oh, I do lots of things—most anything that comes handy, so it ain't work. What's your lay? DUKE: I've done considerable in the doctoring way in my time. Layin' on o' hands is my best holt—for cancer and paralysis, and sich things; and I k'n tell a fortune pretty good when I got somebody to find out the facts for me. Preachin's my line, too, and workin' camp meetin's, and missionaryin' around.After a typically heinous performance, the Duke and Dauphin exit the stage tarred and feathered, ridden out of town on a rail.And yet I spy another crime in that fictional but realistic episode, one potentially far worse than that of our artless flimflam men. As some have commented, the lynch mob can be seen as a ghastly form of theater. Observers of the phenomenon have referred to its "carnival" or "festival" atmosphere. Spontaneous eruptions of civil unrest and mob violence often take theatrical forms, erupt in and around theaters, or have been harnessed by the authorities to serve as spectacles within the theater. The earliest religious ceremonies among tribal peoples often involved human sacrifice. In The Bacchae of Euripides, women possessed by Dionysus during his rites went off into the mountains together to get drunk on wine, dance, and tear live animals apart. Ritual reenactments of murder lay at the heart of every tragedy.The Imperial Romans recognized this human propensity for bloodsport and exploited it by extracting entertainment from their public executions. But more often such mob activity arises spontaneously, requiring no official encouragement. Seldom do such eruptions result in deaths ... more often they serve as a simple (if enthusiastic) critique of those in power, and often with more hilarity than hysteria.By definition, comedy is subversive. It is about defying expectations, turning things upside down, doing things wrong. It is antiauthoritarian. Note how, no matter how much pleasure comedy gives us, we don't speak of going to heaven but rather that "it's funny as hell." Many of us especially prize humor that is irreverent. But irreverence in a theocracy is risky business, as any Catholic-school wiseass knows from the welts on his forearm. Imagine that the entire universe is a Catholic school and instead of a ruler, the nun has a cat-o'-nine-tails.The authorities attempting to Christianize Europe after the fall of Rome had a problem. They were trying to impose their values on a society steeped in centuries of pagan history prior to the spread of the Gospels. Among the hardest habits to break were the ancient holiday traditions, as witnessed by the mysterious intrusion of Christmas trees and Easter eggs in purportedly Christian celebrations. In point of fact the decorated trees and eggs had been cherished pagan symbols for millennia—Christmas and Easter were the Johnny-come-latelies. Christian festivals were scheduled so as to correspond to the old pagan calendar and to co-opt existing folk practices. One such festival was Saturnalia. Held annually in late December, the Roman Saturnalia gave license for a brief return to the "Golden Age of Saturn," an annual experiment in democracy when slaves were treated like kings and all underlings were given deferential treatment by their superiors. As we all know, kings behave like pigs. During Saturnalia, everyone else did too, and thousands of people from every walk of life were allowed to run amok through the streets.In medieval Europe, the offspring of Saturnalia and similar festivals were officially proscribed at the highest levels but tolerated, and eventually facilitated, by the rank-and-file clergy at certain seasons. The reason is simple. Such an event, when practiced by the entire populace, is a difficult thing to control. Think of Woodstock. Half a million people are naked, doing drugs, and having public sex. What are you going to do, arrest them? Prominent among the medieval festivals was the Feast of Fools, which fell between Christmas and Epiphany and has as its obvious descendant April Fool's Day. The Feast of Fools was a period (sometimes spanning several days) when the reigning values were overturned, when the sacred became profane, when the "Lords of Misrule" held sway, and when some lowly sap (a Quasimodo) would be elected "Pope of Fools." Travesty was the law of the land: a donkey said mass ... feces was presented as a sacrament.In these festivals, the emphasis on the "wrong" manifested itself in a celebration of the grotesque, the monstrous. Freaks, giants, dwarfs, and hunchbacks were mockingly elevated to positions of symbolic authority. Stilt-walking, masks, and puppetry allowed performers to be as outwardly strange as their imaginations permitted. Madness and mental retardation as comic material has its roots here; the fools were often literal idiots. The cruel flavor of this sensibility can be found in any good book of English nursery rhymes, the one about "Simple Simon" being only the most obvious example. Vaudevillian Ed Wynn was to play Simple Simon, and the list of his contemporaries who mined the comic possibilities of seeming mad or retarded is long indeed: the Marx Brothers, the Three Stooges, Joe Cook, Clark and McCullough—and so on.These festivals are important to our history, for they enabled professional entertainers to perform for the public with relative impunity. Commedia dell'arte troupes, for example, flourished in the festival environment. Heirs to the vulgar Roman comedy, such clowns earned the people's affection by not shying away from the grossness of the human body or the liberal abuse of it. Then as now the kicking of someone's butt or balls was surefire laugh material. (Innocent as it sounds, that sort of comedy elicited numerous protest letters when it was performed in the films of Charlie Chaplin a scant eighty years ago.)Another dangerous comic tradition that owes much to medieval fooling is the concept of the clown as truth-teller. During the time of festivals, the general public was granted the fool's license to tell it like it is. As we know from Shakespeare, the professional fool had this job as well (though he would do well to exercise a certain amount of caution despite his greater license). The most well-known real-life jester was Will Somers, who had the pluck to jibe the famously irascible Henry VIII, and lived to tell about it. In that tradition, a devastating honesty regardingthe foibles of those in power would characterize many comedians of the vaudeville era—Will Rogers, Frank Fay, Bob Hope, and Groucho Marx among them.Perhaps the most well-known medieval festival was Carnival, celebrated during the season just before the fasting-time of Lent. Its annual traditions of revelry, of abandon, and general joyous hedonism live on today in many European and South American cities, and (in the form of Mardi Gras) in New Orleans. The relationship in Carnival between the antinomian parody and the corporeal transgression it implies is the very reason our word "burlesque" can simultaneously signify a comical spoof, and six—count 'em, six—exotic dancing girls. It's all about living in our bodies ... and crossing over the line.For the most part, these festivals began to tone themselves down by the Renaissance ... at which point the goitered, toothless, illiterate, lice-ridden hordes began to move indoors, where their admission price gave them the right to wreak their vociferous havoc on a nightly basis. Theaters—for centuries—were places where the inebriated audience ate in their seats, then threw their nut shells, orange peels, and apple cores at the performers. They talked throughout the performance, often shouting at the actors, and sometimes even joining them onstage. It would not be unheard of for a show to stop dead because of interference by the audience.Much as most of us do today, the more refined inhabitants of past societies hated this aspect of theatergoing, which until the late nineteenth century was universal. By that time, of course, large contingents of both showfolk and the people who hated them had long since crossed the pond to Yankeeland, where the bulk of our story is set. And so now, to the relief of our Catholic readers, I'm sure, we can start to beat up on the Protestants.In the 1620s and thirties, thousands of Puritans began colonizing the Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, Rhode Island, and Connecticut colonies, laying the groundwork for what was to become one of the dominant forces in American culture for over three centuries. These Puritans felt that the Catholic and Anglican Churches had gotten too rich, fat, and sensuous and had strayed too far from the ascetic teachings of Saint Paul. For the Puritans, pleasure led to sin, and sin led to hellfire. For guidance on the proper tone of human conduct, the Puritans looked tosuch Biblical passages as Luke 6:25: "Woe unto you that laugh now! for ye shall mourn and weep." And James 4:9: "Let your laughter be turned to mourning and your joy to heaviness."Puritan law was based on a literal interpretation of Deuteronomy. The Puritans did not believe in "lascivious dancing to wanton ditties," as John Cotton put it in 1625. For a man to dance with a woman was literally against the law. So was the celebration of Christmas, working on a Sunday, blasphemy, idolatry, cursing out your parents, adultery, and fornication.And, of course, theater, also known as "the Devil's Synagogue," was not exempt from the list of punishable crimes. Well into the eighteenth century, laws forbidding stage plays and other theatrical amusements were still being passed in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, and Connecticut, to name just some. A Boston ordinance from 1750 would "prevent and avoid the many mischiefs which arise from public stage plays, interludes and other theatrical entertainments, which not only occasion great and unnecessary expense, and discourage industry and frugality, but likewise tend greatly to increase impiety and contempt for religion."In Rhode Island, the theater was referred to by one commentator as a "House of Satan." A Newport law forbid "plays, games, lotteries, music and dancing." In Connecticut, a 1773 Act for the Suppressing of Mountebanks forbade "any games, tricks, plays, juggling or feats of dexterity and agility of body ... to the corruption of manners, promoting of idleness, and the detriment of good order and religion." In 1824, President Timothy Dwight of Yale College in his "Essay on the Stage" wrote that "to indulge a taste for playgoing means nothing more or less than the loss of that most valuable treasure the immortal soul." As late as 1872, the Methodists formally proscribed for their members "intoxicating liquors, dancing, playing at games of chance, attending theatres, horse races, circuses, dancing parties, or patronizing dancing schools." At the same time in New York, an Episcopal church refused Christian burial to a prominent actor.Yet, the Thanksgiving myth notwithstanding, America was not exclusively colonized by, nor even founded by, Pilgrims. More to the purpose of our story is America's other origin myth, that of the founding of New York City. The Big Apple had been established not by Puritans or Quakers,but by Dutch merchants. Its storied beginning was not the creation of a City on a Hill, but the swindling of Indians for the purchase of Manhattan. Commerce—and commerce of a rather unsentimental sort—was setting up its tent across from the meeting house. The worshippers of the Real and the Ideal arrived on different boats, but at the same time. Much of American history seems to be about how these two groups learned to accommodate each other. But the Realists ultimately had an edge: men are real, not ideal.Ships were the ruination of the Puritan Utopia. When cities reach a certain width and weight they must perforce tumble off their hills. Travel to Salt Lake City today and you will find ample reminder of the city's Mormon origins and the large number of Latter-Day Saints who still reside there. But the city is no longer exclusively Mormon. Barrooms, strip clubs, and pornographic video stores can be found within city limits, and there's not much the followers of Joseph Smith can do about it—they're outvoted. The early American theocracies underwent a similar process a couple of centuries earlier, as ever-improving modes of sea travel brought millions of non-Puritan immigrants to these shores. Thenceforward proceeds the steady but achingly slow weakening of the Calvinist headlock over the next three centuries.For the first several decades, the American colonies couldn't support professional entertainment even if they had wanted to. In the crude frontier environment, every waking second had to be spent growing food, building shelter, and warding off hostile attacks from wild animals and the native inhabitants. Leisure simply did not exist. But by the mid-eighteenth century, cities like Boston, Williamsburg, New York, and Philadelphia had grown affluent and civilized, permitting free time and division of labor, both necessary conditions for the existence of an entertainment industry. Disputes over the taxation on that wealth were the reason the American Revolution was fought during this period. Indeed, the Revolution forced the closing of the handful of rudimentary theaters built prior to 1776, delaying the real birth of American theater until the eve of the nineteenth century.As Christians might have predicted, the arrival of theater (that descendant of the old Dionysian rites) to American shores brought with it a whole host of familiar temptations. Variety took place in a wide array ofvenues in the nineteenth century, but most everywhere it flourished it was accompanied by the sale of alcohol and all the myriad sins that follow when inhibitions are relaxed. Variety confirmed all of the old prejudices that had been building up over the millennia. From the wine-drenched fertility cults of the Greeks ... to the unspeakable indecencies of Rome ... to the petty cons and thievery of the medieval vagabonds ... to the prostitution that had always been part and parcel of the theatrical package. Fighting, robbery, gambling, whoring—these were among the pitfalls of attending a nineteenth-century American variety show. The association was so powerful that no one could imagine a variety show divorced from those related peccadilloes.How appropriate that the process would largely take part in the city Washington Irving nicknamed Gotham (literally, "goat's town").New York's first theater was the Park, built in 1798. The repertoire consisted mostly of Shakespeare and naughty Restoration sex comedies, with variety entertainment sprinkled fore, aft, and interstitially.With only one theater to choose from, a complete cross-section of the population (apart from religious abstainers) would be in attendance at any show. The president of the United States or the mayor might be there with his retinue. So would mechanics, shopkeepers, dock workers, and, if they could scrape a few pennies together, the homeless. Washington Irving recorded his impressions of New York's first theater audience in 1803. The noise, he said, "is somewhat similar to that which prevailed in Noah's Ark." In addition to the hooting and whistling and yells, people were cracking and eating nuts, crunching apples, and throwing the leftover shells and cores at one another and at the people onstage. This element—this eternal element—is the stuff of which the American audience will be forged.But the day when this one theater could serve the entire population of Gotham was to be short-lived. Technology, geography, and the opportunity to make the most of both, conspired to turn New York City into a permanent boomtown. The theater business would grow along with it. A series of historical developments, coming one atop the other, accounted for this unprecedented phenomenon. In 1820 regularly scheduled passenger service was offered for the first time on packet ships between Liverpool and New York, making transportation cheaper and henceavailable to larger numbers of poor and working-class immigrants. Then, with the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, New York Harbor became the access point for the entire American Midwest. As a consequence, between 1820 and 1835, Manhattan's population more than doubled, from 124,000 to 270,000. The advent of transatlantic steamship service in 1838 meant travel was no longer quite as reliant on the vagaries of the weather. Famine in Ireland and social unrest in Germany in the 1840s brought large numbers from those countries on those steamships, and the influx continued into the twentieth century. By 1860, New York's population was over a million.The explosion, the first of many, would catapult New York from a position of relative parity with its modest sister cities in the Americas to a world-class metropolis on a par with London, Paris, and Berlin. Everincreasing growth and prosperity ensured an audience for, and a speculative market in, new and diverse entertainment venues. By 1840 there were twelve theaters; by 1860, thirty-two; and by 1880, sixty-two. Eight decades before, there had only been one.Theatergoing changed to reflect these shifting demographics. The Bowery Theatre (built 1826), seated a thousand more patrons than the Park. To fill those seats, its manager increasingly reached out to a new audience, the emerging working class, composed largely of immigrants, who were now enjoying their unprecedented wages and leisure time. The lion's share of these new arrivals didn't care a fig for Puritan values—that was for the old-guard upper and middle classes. They wanted a rip-roaring good time.To give them one, the Bowery Theatre managers, and their many imitators, stressed the more spectacular elements, producing blood-and-guts melodramas, truncated versions of Shakespeare ("da good parts"), swashbucklers, and bodice-rippers, calculated to get the Bowery b'hoys and g'hals worked into a lather. In America in the nineteenth century, as theater historian Robert M. Lewis put it, "every program in the theater was a variety show." An evening's entertainment, even a well-respected classical drama, was liable to be wrapped in a package of variety, with preshows, postshows, and entr'actes that could consist of anything from dancers to banjo players to opera singers to jugglers to opening prologues not so far removed from stand-up comedy. An 1838 bill featuredShakespeare, ballet, sentimental ballads, and an exhibition of the "Science of Gymnastics." During her first American tour, Sarah Bernhardt was discomfited to find the acts of her Camille broken up by can-can dancers and a xylophone player.Meanwhile, the drunken rabble in the audience would hoot, holler, throw firecrackers, coins, and spoiled fruit, have fistfights, and periodically get up onstage and join the show. One imagines the atmosphere of a pro wrestling match, mixed with a monster truck rally, a cockfight, and the bleachers at Yankee Stadium. The theater was no longer the sort of place where you might find George Washington and Alexander Hamilton. Instead, you met guys with names like "Spike" and "Crusher," and women with names like "Peaches."By the 1830s, we have the first splitting of the American theatrical protozoa. At that time we can identify two separate entertainment markets, as the more discriminating theatergoers and hoi polloi start to peel apart, each group seeking a theatrical experience closer to its own tastes. The "legitimate" theater, of which the Park Theatre was for a time to be the principal exemplar, strove to differentiate itself from the raucous working-class entertainments offered by its principal competition on the Bowery. Within a few decades' time the stratification became so marked that vaudeville managers would have to haggle (and pay dearly) to convince stars like Sarah Bernhardt, Ethel Barrymore, and Mrs. Patrick Campbell to stoop to do a turn on their stages. "Legit" was the playground of cultured WASPs. Newer arrivals swam in the swamp of the "popular theater."In the early-mid-nineteenth century the most important faction in this heaving demos was the outsized component of newly arrived Irish Catholics. Because of a peculiar set of historical circumstances, they at once constituted a hated Other in a manner reminiscent of the Jews and Gypsies back in Europe, yet they were also numerous enough to prove a decisive cultural force.The performers of the variety stage were overwhelmingly Irish. Their dominance of early show business, of course, has to do with anti-Irish prejudice and a lack of other options for them to get ahead. When they first arrived, the Irish, it is well-known, were discriminated against, spat upon, and made the victims of what we would today call hate crimes."No Irish Need Apply." George Templeton Strong averred that "our Celtic fellow citizens are almost as remote from us in temperament and constitution as the Chinese." In 1855, after ten years of massive immigration in the wake of the Irish Potato Famine, 86 percent of New York's laborers were Irish, as were 74 percent of the city's domestics. Dig a ditch or dance a jig—which would you rather do? Interestingly, the Irish first made their mark by impersonating yet another group of beleaguered Americans even lower than themselves on the social scale.Around 1830, while touring the theaters of the Ohio valley, a performer named T. D. (Thomas Dartmouth) "Daddy" Rice blackened his face with burnt cork, took the stage, and impersonated a crippled slave he had seen working in a stable. The tune and the dance he performed (both appropriated from the slave, according to Rice) were called "Jim Crow"—hence the origin of the nickname for the South's old system of oppressive discriminatory laws.Turn about and wheel about an' do just so Every time I turn about I jump Jim Crow!The act was wildly successful wherever Rice went—not just in the South and West, but also back in his hometown of New York, where, starting in 1832, he enjoyed a lengthy run at the Bowery Theatre. His debut was such a smash that (legend has it) the audience demanded he repeat the number twenty times in a row.In Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, author Eric Lott notes that most of the key performers and writers in minstrelsy were Irish-Americans: Stephen Foster, Dan Emmet, Dan Bryant, Joel Walker Sweeney, and George Christy among them. Their participation in a performance genre that degraded another race may well have had to do with their own feelings of inferiority relative to the native-born WASP Americans, who likewise looked down on them.Blackface, some historians aver, has origins far older than American slavery. The practice can be traced, in fact, to those very same medieval festivals discussed earlier, where, in the atmosphere of general lawlessness, amateurs performed charivaris and mummers' plays with blacked-upfaces, flitting from house to house through the night like grown-up trick-or-treaters. The tradition had always had more of the trick than the treat about it. Ironically, it stems from the same medievalist impulse that gave birth to the hoods and robes of the Ku Klux Klan. Masks are made for mischief—and sometimes dangerous mischief, at that.Times change, though, and what offends us today about blackface—that it was a cruel and unfair misrepresentation of a group of Americans who were powerless to protest it—is actually the very opposite of what might have offended certain sensibilities in the nineteenth century. From a modern perspective, when we think of blackface comedy, or comedy demeaning to blacks (often portrayed by actual blacks), we are apt to conjure the most accessible examples available to us: old episodes of Amos and Andy, Stepin Fetchit movies, and so forth. This kind of comedy was without a doubt derogatory. Yet objections to blackface and minstrelsy on the basis of racism were few and far between until after the First World War, when enough political will was finally mustered to shame the practice. Instead, when minstrelsy arrived in the nineteenth century, observers were more concerned because the portrayals of African-Americans in minstrelsy seemed not false, but truthful, and thus vulgar. In other words, the manners and body language of Africans were considered so uncouth that to mimic them onstage was a sort of indecent display, not unlike that perpetrated by the exotic dancers down at your local strip club.Just as women were said by some to be daughters of Eve, blacks were thought to be the sons and daughters of Ham, the cursed son of Noah, whose descendants according to Genesis were condemned to be the servants of the rest of mankind. Some did not even consider blacks to be human beings. But even those who conceded Africans membership in the human race—on a par with Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, and others—considered them part of some other, far more primitive, branch of humanity. Like women, blacks were viewed as simple, instinct-driven, childlike, and somehow closer to Satan.This impression was enhanced by the nature of African religion, which to Christians resembled nothing so much as satanic ritual. From the lands of western Africa, where almost all of the American slaves originated, came the polytheistic religions that would evolve in the NewWorld into voodoo. With totems, drumming, and trance-inducing dances, these practices were shocking to Europeans encountering them for the first time. Traveler Alexander Hewatt wrote in 1779:... the Negroes of that country [South Carolina], a few only excepted, are to this day as great strangers to Christianity, and as much under the influence of Pagan darkness, idolatry and superstition, as they were at their first arrival from Africa ... Holidays there are days of idleness, riot, wantonness and excess: in which the slaves assemble together in alarming crowds, for the purposes of dancing, feasting and merriment.Sounds a lot like Carnival. No small wonder then, that in New Orleans, African voodoo culture would merge with French medieval festival traditions, resulting in Mardi Gras.Music and dance were crucially important to all aspects of African society, pervading not only their religious customs but their social ones. In this realm, consequently, culture clash was at its greatest. Early Euro-American accounts of African dance are frank in their disdain and disgust, describing the movements as "savage," "lascivious," "sinuous," and "snakelike." After all, not long before, American Protestant zealots had banned all singing and dancing.The musical tastes of the American middle class in the mid-nineteenth century ran to classical music and hymns. Suddenly a bunch of prominent stage performers—many of them Irish Catholics, no less—were undertaking to impersonate Africans onstage. These performances were part lampoon, part wish fulfillment. Masks are ideal enablers, and by impersonating blacks, these performers now had the freedom to engage in all manner of startling and liberating behavior that no self-respecting white man would ever dare to openly attempt.It may be well to pause a moment and consider the cultural implications of the mass importation of vast numbers of Africans into this culture of White Anglo-Saxon Protestants. For, as much as integration between the two culturally polar groups moved with glacial slowness (indeed remains unfinished), the African-American made his cultural influence felt so keenly that it might rightly be said that it is the single most distinctive ingredient of American culture."The irony of the situation," wrote Alain Locke, "is that in folk-lore, folk-song, folk-dance, and popular music the things recognized as characteristically and uniquely American are products of the despised slave minority ..." That such a thing has happened would have been deemed impossible by the whites of the nineteenth century.In minstrelsy, black and white traditions merged in a sort of cultural miscegenation. Irish jigs, reels, and schottisches were intermixed with African shuffles and breakdowns. Popular, joyous, and nonsensical dialect tunes were written, ostensibly borrowed from plantation melodies but more often based on old English and Irish folk songs, made to serve the new form by spicing them up with recognizable "darky" lyrics full of slang and bad grammar and pronunciation. African musical instruments were pressed into service, bringing a new percussive element into the music. The most important of these had first been encountered by white men in Africa in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A stringed instrument made out of a hollow gourd and a piece of wood, it was referred to variously as a banza, a banshaw, a banjar, a banjil, and a bangoe until posterity finally settled on "banjo." By 1819 it had evolved into a form familiar to us as that instrument, and was common on plantations until blackface minstrels like Rice, Dixon, and Sweeney began to popularize it on the American stage. Widespread too were the tambourine and the "bones," a pair of curved animal bones clicked together in the hand after the fashion of castanets.Minstrelsy's cultural legacy makes the form extremely problematic for the vaudeville fan. On the one hand, its racial depictions are uniformly heinous. At its very best, it is merely patronizing. But, on the other hand, minstrelsy's songs, sketches, monologues, and overall format laid the foundation for the character of American show business for all time. American popular music of every conceivable type (ragtime, jazz, blues, bluegrass, country) owes something to it, as do all American solo, improv, and sketch comedy. Minstrelsy is like Hitler's Volkswagen—a very good car invented by and for Nazis.For example, minstrelsy's pop tunes were so catchy that many of them are still "on the charts" 150 years later. Far and away the most successful minstrelsy songwriter was Stephen Foster, who wrote songs for both T. D. Rice and E. P. Christy. His hits (all of which are still in circulation) include "Old Folks at Home (Swannee River)," "Camptown Races," "MyOld Kentucky Home," and "Old Black Joe." Another important songwriter from the minstrelsy stage was James Bland (an African-American) who wrote "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny" and "O Dem Golden Slippers."And then there is the invention of the comedy team. The minstrel songs would be interspersed with comic dialogue between a character known as Mr. Interlocutor (or, the "middle man") and his two "end men," Mr. Tambo and Mr. Bones. These stock characters were so called because the former played the tambourine, and the latter played the bones. Mr. Interlocutor was more subdued than the others, a sort of stiff, humorless master of ceremonies to bounce jokes off of. Some of the jokes they told, and the manner in which they told them, would be familiar to any child over the age of five:END MAN: Say, boss, why did the chicken cross the road? MIDDLE MAN: Why, I don't know, Mr. Tambo, why did the chicken cross the road? END MAN: To get to the other side!This joke has become so well-known that it has ceased to be a joke. It is woven into our very cultural fiber. We know it as well as we know the Ten Commandments, and in some deplorable cases, better.It would be hard to overstate how hugely influential the whole Tambo-Bones-Interlocutor comedy axis was. Any two-man comedy act (often called a "two-act") in the history of show business owes something to it. Mr. Interlocutor is the original straight man, Tambo and Bones the original stooges. The kind of rapid-fire interplay between them (known as crosstalk) would be perpetuated by everyone from Weber and Fields, to Smith and Dale, to Burns and Allen, to Abbot and Costello, to Lewis and Martin, to Rowan and Martin, to Ren and Stimpy.Minstrelsy also exerted an influence on the format of American variety. The centerpiece of the minstrel show, called the "olio," was a pure variety show. The olio was very much like a crude form of vaudeville, featuring specialty acts like a banjo or fiddle player, a "stump speech" full of comic malapropisms, a drag act (known as the "wench"), Scotch and Irish jig dancers, and the like. So, while the minstrel show is American show business's original sin, it is also the ancestor of all we hold dear. Family histories are like that.Ethnic lampoon by no means replaced the older, more traditional vices that had always been associated with the stage. For example, as had been the case for centuries in Europe, New York's theaters in the nineteenth century were as good as a street corner or a wharf for making assignations with ladies of the evening. John Jacob Astor had seen to that when he bought the Park Theatre in 1806 and outfitted it with special accommodations for hookers, giving them their own designated entrance and a section in the third-tier balconies where gentlemen could meet them and set up appointments. Though scandalous-sounding, this was a fairly pragmatic approach to take. His customers were bound to use his theater for such purposes anyway. (Yet how like the American businessman to devise a modern system to meet the needs of the oldest profession!) Not to be outdone, Astor's competitors at the Bowery, the Chatham, and the Olympic theaters all followed suit. For decades, no New York theater was without such a facility. Most opened an hour or two before showtime to allow the girls and their clients the opportunity to mix, mingle, make dates, and, most important, buy drinks at the bar. In time, particularly at the lower-class theaters, the girls grew more brazen, working the aisles, the bar, and the neighborhood around the theater. Scores of them—as much as a quarter of the audience—might be in attendance at any given performance. Brothels were built in the neighborhoods nearby, for the added convenience of men on the town, who generally made their dates right in the theaters.As degenerate activities at the theater escalated, patronage by "respectable" people correspondingly dwindled. Partly to escape the mobs of the Bowery, Manhattan's upper crust moved uptown, far from the theater district. In so doing, they built themselves a sort of cocoon of virtue. The explosion of religious fervor in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries known as the Second Great Awakening, along with the advent of Queen Victoria's reign, had made propriety and virtue fashionable with the upper class and the newly emergent middle class. "We are not amused," Victoria had famously pronounced—and she did her best to see that no one else was, either. Largely through her influence, a new "cult of domesticity" held sway, making it desirable for families to stay home in the evenings and console themselves with simple pleasures. For laughs, women might sit around in a circle embroidering pillows. Children were expected to play silently, perhaps with a toyNoah's Ark, or a fragile ceramic doll. Men just sat in the corner grinding their teeth and watching the minute hand of the grandfather clock, praying, PRAYING for sleep to come ...Yet men had options that their wives did not. While the women remained the guardians of the hearth from dawn to dusk, the men toiled downtown, close to the theatrical district. This made it extremely convenient to stay out late on some pretext in order to behave less virtuously than they professed to be. The Bowery and lower Broadway provided an environment where a man could have intimate conversations with the sort of people he ordinarily wouldn't be caught dead talking to. In Victorian New York, it seems that every Jekyll had his Hyde. And the elixir that effected all those transformations was both ancient and plentiful: the active ingredient was alcohol.Liquor had always been an integral feature of theatergoing, from the wine cult of Dionysus straight on through. Bibulousness began to reach new high (or lows), however, when advances in distillation made cheap whiskey widely available after the 1820s. Taverns, the relatively sedate and cozy institutions of yore, where a traveler could enjoy a meal, a mug of grog, a bowlful of tobacco, and a bed for the night, began to morph into a more specialized alcohol-delivery emporium, called a "salon" until ugly Americans began to mispronounce it, at which point it became a "saloon." By the 1850s, fairly elaborate variety shows were staged at the largest of these, which became known as "concert saloons."In the post—Civil War economic boom, some three hundred such establishments existed in New York alone. Sections of Manhattan were like the Wild, Wild East.In its rough-and-tumble heyday the Bowery was something like Times Square, Coney Island, Ripley's Believe It or Not Odditoriums, and Atlantic City all rolled into one, full of bars, gambli

\ From the Publisher"No Applause is a fabulous book worthy of its fabulous topic. Clever, thoughtful, and comprehensive, it is beautifully written and exhaustively researched, and it reminds us of the myriad ways in which vaudeville dominated urban America for half a century and more." —Kenneth T. Jackson, professor of history, Columbia University and editor of The Encyclopedia of New York City\ "Trav S.D. has created an essential (and very funny) history of American popular entertainment, particularly for those of us trying to create popular entertainment today." —Greg Kotis, creator of Urinetown\ \ \