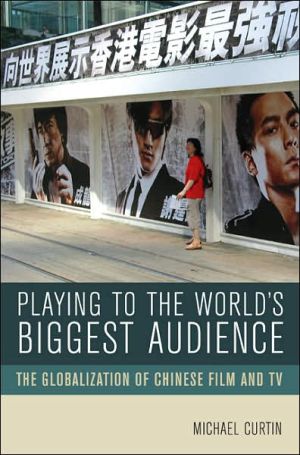

Playing to the World's Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV

In this provocative analysis of screen industries in China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, Michael Curtin delineates the globalizing pressures and opportunities that since the 1980s have dramatically transformed the terrain of Chinese film and television, including the end of the cold war, the rise of the World Trade Organization, the escalation of democracy movements, and the emergence of an East Asian youth culture. Reaching beyond national frameworks, Curtin examines the prospect of a...

Search in google:

"Professor Curtin has woven solid research and interesting tales into a compelling analysis of cultural geography that will make an important contribution to the literature of international communication."—Chin-Chuan Lee, City University of Hong Kong"In this timely and fascinating examination of the screen industries of 'Global China', Michael Curtin draws on in-depth interviews with key industry players to provide, for the first time, a comprehensive analysis of the extraordinary rise of film and television industries across Chinese-speaking Asia. In so doing he provides a compelling account of how these media industries represent a powerful alternative path of media globalization to that of the West. This will be essential reading for anyone who wants to understand the dynamics and complexities of globalized media production. But more than this, his deployment of the concept of 'media capital' and his stress on the particularities of culture, creativity and location offer important political-economic and institutional underpinnings for a more rigorous approach to understanding wider patterns of cultural globalization."—John Tomlinson, author of Globalization and Culture"This is one of the best books I've encountered. Curtin's scholarship is superior and his approach is highly innovative. Playing to World's Largest Audience is a pioneering work in understanding globalization and Chinese media. It will have major impact in numerous fields."—Emilie Yueh-yu Yeh, author of Taiwan Film Directors and East Asian Screen Industries

Playing to the World's Biggest Audience\ The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV \ \ By Michael Curtin \ University of California Press\ Copyright © 2007 The Regents of the University of California\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-520-25134-2 \ \ \ Introduction\ Media Capital in Chinese Film and Television \ At the turn of the twenty-first century, feature films such as Crouching Tiger, Kung Fu Hustle, and Hero-each of them coproduced with major Hollywood studios-marched out of Asia to capture widespread acclaim from critics, audiences, and industry executives. Taken together they seemed to point to a new phase in Hollywood's ongoing exploitation of talent, labor, and locations around the globe, simply the latest turn in a strategy that has perpetuated American media dominance in global markets for almost a century and contributed to the homogenization of popular culture under the aegis of Western institutions. These movies seem to represent the expanding ambitions of the world's largest movie studios as they begin to refashion Chinese narratives for a Westernized global audience. Yet behind these marquee attractions lies a more elaborate endgame as Hollywood moguls reconsider prior assumptions regarding the dynamics of transnational media institutions and reassess the cultural geographies of media consumption. For increasingly they find themselves playingnot only to the Westernized global audience but also to the world's biggest audience: the Chinese audience.\ With more than a billion television viewers and a movie going public estimated at more than two hundred million, the People's Republic of China (PRC) figures prominently in such calculations. Just as compelling, however, are the sixty million "overseas Chinese" living in such places as Taiwan, Malaysia, and Vancouver. Their aggregate numbers and relative prosperity make them, in the eyes of media executives, a highly desirable audience, one comparable in scale to the audience in France or Great Britain. Taken together, Chinese audiences around the globe are growing daily in numbers, wealth, and sophistication. If the twentieth century was-as Time magazine founder Henry Luce put it-the American century, then the twenty-first surely belongs to the people that Luce grew up with, the Chinese. Although dispersed across vast stretches of Asia and around the world, this audience is now connected for the very first time via the intricate matrix of digital and satellite media.\ Rupert Murdoch, the most ambitious global media baron of the past twenty years, enthusiastically embraced the commercial potential of Chinese film and television when in 1994 he launched a stunning billion-dollar takeover of Star TV, Asia's first pancontinental telecaster, founded only three years earlier by Li Ka-shing, Hong Kong's richest tycoon. Yet if Western executives are sharpening their focus on Chinese audiences, Asian entrepreneurs have been equally active, expanding and refiguring their media services to meet burgeoning demand, so that today, in addition to Star, hundreds of satellite channels target Chinese audiences in Asia, Europe, Australia, and North America, delivering an elaborate buffet of news, music, sports, and entertainment programming. Among Star's leading competitors is TVB, a Hong Kong-based media conglomerate built on the foundations of a transnational movie studio and now the most commercially successful television station in southern China. Its modern state-of-the-art production facilities and its far-reaching satellite and video distribution platforms position it as a significant cultural force in Europe, Australia, and North America. Equally impressive, Taiwanese and Singaporean media enterprises are extending their operations abroad in hopes of attracting new audiences and shoring up profitability in the face of escalating competition, both at home and abroad. Finally, PRC film and TV institutions, though still controlled by the state and therefore constrained by ideological and infrastructural limitations, are globalizing their strategies, if not yet their operations, regularly taking account of commercial competitors from abroad and aiming to extend their reach as conditions allow.\ Based on in-depth interviews with a diverse array of media executives, this book peeks behind the screen to examine the operations of commercial film and television companies as they position themselves to meet the burgeoning demands of Chinese audiences. It includes stories of Hong Kong media moguls Run Run Shaw and Raymond Chow as well as their junior counterparts, Thomas Chung and Peter Chan; of Rupert Murdoch and his enigmatic mainland partner, Liu Changle; of Sony chair Nobuyuki Idei and his Connecticut whiz-kid, William Pfeiffer. It also includes tales of legendary Asian billionaires, such as Li Ka-shing, Koo Chen-fu, and Ananda Krishnan, lured by the scent of fresh new markets, as well as stories of aspiring billionaires Chiu Fu-sheng and Richard Li, each determined to find a seat at the table for what is becoming one of the most high-stakes media plays of the new millennium.\ But this volume is more than a collection of colorful accounts of personal and corporate ambition; it is furthermore a reflection on the shifting dynamics of the film and television industries in an era of increasing global connectivity. For several centuries, the imperial powers of the West exercised sway over much of the world by virtue of their economic and military might. In time, cultural influence came to figure prominently in Western hegemony, as the production and distribution of silver screen fantasies helped to disseminate capitalist values, consumerist attitudes, and Anglo supremacy. Likewise, Western news agencies dominated the flow of information, setting the agenda for policy deliberations worldwide. Indeed, throughout the twentieth century, media industries were considered so strategically significant that the U.S. government consistently sought to protect and extend the interests of NBC, Disney, Paramount, and other media enterprises. All of which helps to explain why Hollywood feature films have dominated world markets for almost a century and U.S. television has prevailed since the 1950s. Besides profiting from government favoritism, U.S. media has benefited from access to a large and wealthy domestic market that serves as a springboard for their global operations. By comparison, for most of the twentieth century, the European market was splintered, and the Indian and Chinese markets suffered from government constraints and the relative poverty of their populations. Yet recent changes in trade, industry, politics, and media technologies have fueled the rapid expansion and transformation of media industries in Asia, so that Indian and Chinese centers of film and television production have increasingly emerged as significant competitors of Hollywood in the size and enthusiasm of their audiences, if not yet in gross revenues.\ In particular, Chinese film and television industries have changed dramatically since the 1980s with the end of the Cold War, the rise of the World Trade Organization, the modernization policies of the PRC, the end of martial law in Taiwan, the transfer of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty, the high-tech liberalization of Singapore, the rise of consumer and youth cultures across the region, and the growing wealth and influence of overseas Chinese in such cities as Vancouver, London, and Kuala Lumpur. Consequently, media executives can, for the very first time, begin to contemplate the prospect of a global Chinese audience that includes more moviegoers and more television households than the United States and Europe combined. Many experts believe this vast and increasingly wealthy Global China market will serve as a foundation for emerging media conglomerates that could shake the very foundations of Hollywood's century-long hegemony.\ Despite these changes, Hollywood today is nevertheless very much like Detroit forty years ago, a factory town that produces big, bloated vehicles with plenty of chrome. As production budgets mushroom, quality declines in large part as a result of institutional inertia and a lack of competition. Like Detroit, Hollywood has dominated for so long that many of its executives have difficulty envisioning the transformations now on the horizon. Because of this myopia, the global future is commonly imagined as a world brought together by homogeneous cultural products produced and circulated by American media, a process referred to by some as Disneyfication. Other compelling scenarios must be considered, however. What if, for example, Chinese feature films and television programs began to rival the substantial budgets and lavish production values of their Western counterparts? What if Chinese media were to strengthen and extend their distribution networks, becoming truly global enterprises? That is, what if the future were to take an unexpected detour on the road to Disneyland, heading instead toward a more complicated global terrain characterized by overlapping and at times intersecting cultural spheres served by diverse media enterprises based in media capitals around the world? Playing to the World's Biggest Audience explains the histories and strategies of commercial enterprises that aim to become central players in the Global China market, and in so doing it provides an alternative perspective to recent debates about globalization.\ Transcending the presumption that Hollywood hegemony is forever, this volume joins a growing literature that is beginning to offer alternative accounts of global media. Playing describes the challenges and opportunities that confront Chinese commercial media, and it shows, unexpectedly, that these industries are nurturing a fertile breeze of democratization that is wafting across Asia today. The winds of change are gusty and unpredictable, nevertheless, and sometimes given to dramatic reversals. After more than a decade of torrid expansion, commercial media enterprises were hit hard by the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the dotcom meltdown of 2000, and a dramatic escalation of digital piracy. By the end of the last century, Chinese media enterprises were for the very first time thoroughly globalized in outlook but had slowed the pace of their expansion while seeking to consolidate their operations and reformulate their business plans. The focus of this book therefore is on the wave of globalization during the 1990s and early 2000s, providing a context for analyzing the current constraints and future opportunities of these industries. It focuses furthermore on commercial media enterprises, although some discussion of state media in the PRC is offered to present a more inclusive account of the market dynamics driving Chinese media. In all, my aim is to portray the ways in which successful Chinese media enterprises have adapted-at times grudgingly or haphazardly-to the shifting social and institutional dynamics of the global millennium.\ By venturing into the realm of transnational media, markets, and culture, this book traverses a terrain of critical research that has been strongly influenced by theories of media imperialism. Two of the early proponents of this approach, Thomas Guback and Herbert Schiller, published contemporaneous assessments of international film and television in the late 1960s, providing foundational explanations of the ways in which American media institutions extended their influence overseas during the twentieth century. Both describe self-conscious collaboration between media executives and government officials seeking cultural, commercial, and strategic influence abroad. Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart elaborated this approach by showing how national elites in South America were complicit with practices that promoted cultural hegemony of leading industrialized nations. Karl Nordenstreng and Tapio Varis furthermore contributed potent empirical evidence of television programming exports from the West to the rest of the world, arguing that trade imbalances were part of larger structural patterns of dominance. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s this body of scholarship flourished, asserting that the United States and its European allies control the international flow of images and information, imposing media texts and industrial practices on unwilling nations and susceptible audiences around the world. According to this view, Western media hegemony diminishes indigenous production capacity and undermines the expressive potential of national cultures, imposing foreign values and contributing to cultural homogenization worldwide.\ The basic unit of analysis for researchers of media imperialism was the modern nation-state, which meant that domination was usually figured as a relationship between countries, with powerful states imposing their will on subordinate ones, especially in news reporting, cinematic entertainment, and television programming. On the basis of data gathered in the 1960s and 1970s, when American media had few international competitors, media imperialism's founding scholars initially anticipated enduring relations of domination, presuming that media exporters would be able to perpetuate their structural advantages. So influential was this critique that it helped to inspire an energetic reform movement among less developed nations, calling for the New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO), a campaign that crested in the 1980s with a set of United Nations reform proposals that would have sailed through the General Assembly if not for the fierce opposition of the Reagan and Thatcher governments, both champions of "free flow" over the reformers' demands for "fair and balanced flow." This neoliberal, Anglo-American alliance thoroughly undermined the momentum behind NWICO and furthermore mounted a counteroffensive aimed at promoting the marketization of media institutions around the world.\ When this concerted political assault on NWICO started to emerge from the political right, scholars on the left also began to critically reexamine some of the essential tenets of the media imperialism thesis. One of the first and most telling critiques was posed by Chin-Chuan Lee, a young scholar from Taiwan who interrogated the theoretical consistency and empirical validity of the media imperialism hypothesis by considering case studies of media in Canada, Taiwan, and the People's Republic of China. Lee argued that foundational assumptions, such as a correspondence between economic domination and media domination, simply did not hold up under close scrutiny. Canada, a wealthy developed nation, was thoroughly saturated by Hollywood media, while Taiwan, a thoroughly dependent and less developed nation, had established a relatively independent media system that nevertheless failed to nurture "authentic" local culture, preferring instead commercial hybrid forms of mass culture. The PRC, although least developed of the three, was even more removed from Hollywood domination but thoroughly authoritarian, making it the most elitist and least popular media system at the time. Supporting neither free flow doctrines nor the media imperialism critique, Lee argued for middle-range theories and regulatory policies that would be sensitive to the complexities of specific local circumstances.\ Scholars in cultural studies and postcolonial studies also began to question media imperialism, especially the presumption that commercial media industries had clear and uniform effects on audiences. Might audiences read Hollywood's dominant texts "against the grain," they wondered? Might they be more strongly influenced by family, education, and peer groups than by foreign media? Critics also challenged the presumption that all foreign values have deleterious effects, noting that the emphasis on aspiration and agency found in many Hollywood narratives might actually have positive effects among audiences living in social systems burdened by oppressive forms of hierarchy or patriarchy or both. Moreover, critics pointed to the media imperialism school's troubling assumption that national values were generally positive and relatively uncontested, arguing, for example, that in the case of India, national media tended to cater to Hindu elites at the expense of populations from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, such as Tamil and Telegu. Moreover, they pointed out that cultures are rarely pure, autonomous entities, since most societies throughout history have interacted with other societies, creating hybrid cultural forms that often reenergize a society by encouraging dynamic adaptations. According to these critics, media imperialism's notion of a singular, enduring, and authentic national culture simply overlooks the many divisions within modern nation-states, especially in countries that emerged with borders imposed by their former colonial masters, such as Indonesia and Nigeria. Overall, cultural studies scholars pointed out that media imperialism's privileging of "indigenous culture" tends to obscure the complex dynamics of cultural interaction and exchange.\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Playing to the World's Biggest Audience by Michael Curtin Copyright © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California. Excerpted by permission.\ All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Acknowledgments ixIntroduction: Media Capital in Chinese Film and Television 1The Pan-Chinese Studio System and Capitalist Paternalism 29Independent Studios and the Golden Age of Hong Kong Cinema 47Hyperproduction Erodes Overseas Circulation 68Hollywood Takes Charge in Taiwan 85The Globalization of Hong Kong Television 109Strange Bedfellows in Cross-Strait Drama Production 133Market Niches and Expanding Aspirations in Taiwan 151Singapore: From State Paternalism to Regional Media Hub 176Reterritorializing Star TV in the PRC 192Global Satellites Pursuing Local Audiences and Panregional Efficiencies 211The Promise of Broadband and the Problem of Content 229From Movies to Multimedia: Connecting Infrastructure and Content 245Conclusion: Structural Adjustment and the Future of Chinese Media 269Industry Interviews 291Notes 295Bibliography 313Index 325