Pre-Gay L.A.: A Social History of the Movement for Homosexual Rights

This book explores the origins and history of the modern American movement for homosexual rights, which originated in Los Angeles in the late 1940s and continues today. Part ethnography and part social history, it is a detailed account of the history of the movement as manifested through the emergence of four related organizations: Mattachine, ONE Incorporated, the Homosexual Information Center (HIC), and the Institute for the Study of Human Resources (ISHR), which began doing business as ONE...

Search in google:

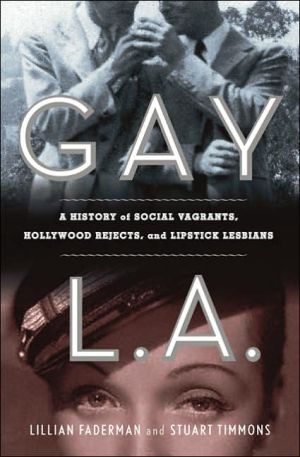

A rich and definitive history of the gay rights movement's West Coast origins.

Pre-Gay L.A.\ A Social History of the Movement for Homosexual Rights \ \ By C. TODD WHITE \ UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS\ Copyright © 2009 C. Todd White\ All right reserved.\ ISBN: 978-0-252-03441-1 \ \ \ Chapter One\ Mattachine (1948–52) \ It would not be too much of a stretch to see the Mattachine's Harry Hay as a visionary, perhaps even a prophet. —Bert Archer, The End of Gay (and the Death of Heterosexuality)\ The Harry Hay of the '50s had all the humor of Moses striding down the mountain with that dratted Decalogue. —Dale Jennings (as quoted in Hansen, A Few Doors West of Hope)\ IT WOULD SEEM that today's lesbian and gay rights movement, commonly referred to as the LGBT or LGBTQ movement since it came to include the rights of bisexual, transgendered, and queer people, began in 1950 largely through the efforts of one man, Harry Hay. More has been written about Hay, often lauded as the "father" of the gay rights movement, than about any other pioneer of the Los Angeles homosexual movement.\ Henry "Harry" Hay was born on April 7, 1912, in Sussex, England, and raised in an upper-middle-class neighborhood in Los Angeles. His first sexual encounter was with a sailor named Matt, whom he met on a steamship bound for Los Angeles, when he was fourteen. After their encounter, the sailor gave Hay a bit of prophetic advice that Hay later claimed was "the most beautiful gift that any older man ever gave a younger man": "Someday you're going to come to a port, and you won't understand a word that's said around you, and you won't see a face, you won't get a smell that's familiar to you at all and you'll be frightened, and terrified, and afraid. And all of the sudden across this room, because you're a tall boy, you'll see a pair of eyes open and glow, at you, as you lift your eyes open and glowing at him. At that moment of eye lock you are home, and you are safe, and you are free. This is my gift."\ From this experience, Hay came to believe that homosexual men comprised a secret, sacred brotherhood, with an imperative to "protect each other's anonymity with [their] lives": "Over the centuries, this is how we have managed to stay alive and this is how we have managed to prevail: we have always guarded each other's anonymity as if it were our own, because if I guard you, you in turn will guard me and that's the only safety we've got. I've never forgotten this; it is something that was embedded in my very young mind and I've remembered this many, many times."\ An active and articulate scholar through high school, Hay graduated with honors in 1929 and then spent the next year working for an attorney in a downtown office (Licata 1978, 105). During this time, he discovered "cruising" in nearby Pershing Square and had a sexual encounter there with an older man called "Champ," who was probably in his early thirties (Licata 1978, 106). In 1931, Hay left Los Angeles to matriculate at Stanford University, but he did not complete a degree. In the fall of 1932, after having an affair with James Broughton and coming out to his classmates as "temperamental," he moved back to Los Angeles. The next February, Hay became an actor for the Antonio Pastor Theatre, performing character and comedy roles. He soon began dating Will Geer, the theater's lead actor, who would later become famous as Grandpa Walton (Hay 1996, 356; Slade 2001).\ Hay was first drawn to social activism in 1934 when he witnessed a V-shaped wedge of mounted police force their way through a crowd of people gathered before the Los Angeles City Hall, demonstrating for milk. As described by Licata, Hay "grew furious" with what he saw. "Hay hurled a rock, which hit the lead policeman, knocking him from his horse. He was saved from arrest when a friendly Mexican-American pulled him into a maze of humble dwellings that scaled the nearby hill" (1978, 107). Hay later told Will Roscoe that a well-known drag queen named Clarabelle helped usher him to safety as he escaped into Bunker Hill (Hay 1996, 356; Roscoe 1996b, 37). Later that year, a second event was to make a life-changing impression on him. He had traveled with Geer to San Francisco to participate in the longshoremen's strike of 1934. When the National Guard opened fire on the crowd, Hay heard bullets whizzing past his ear. Two people were killed and many others wounded. A funeral march followed with a procession of 100,000 people that snaked its way through the streets of the city. Here, Hay first glimpsed the "power of the people" and knew that it was mobilizing the masses where real power lay—the power to change and to improve society (Slade 2001).\ Hay had been attending Communist Party meetings since February 1933. Under directives from Moscow, the party at that time attempted to form coalitions with all other groups opposed to fascism, even if ideologically they opposed socialism. This "Popular Front" policy "called on artists to foster social consciousness and mobilize the masses through art" (Roscoe 1996b, 38). Such tactics proved somewhat successful in Los Angeles, where "many of the writers, actors, and crafts people in the burgeoning film industry joined Popular Front organizations." Hay was hooked—he had certainly found his place. "He signed up for nearly every progressive cause and organization that arose in the 1930s" (Roscoe 1996b, 38) and remained an active party member for the next eighteen years (Katz 1992, 412).\ From 1939 to 1942, Hay lived in New York where he studied the lives and works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and intended to become a Communist Party teacher (Roscoe 1996b, 39). According to Licata, "Hay introduced folk singing into the progressive left, putting on Hootenannies with talent such as Pete Seeger, Burl Ives, Leadbelly, and Woody Guthrie" (1978, 107). He learned at this time the efficacy of music, pageantry, theater, and ritual in social movements. If those cultural elements were focused on a social cause, one could build a formidable movement around a core of common values through which common objectives could be thoughtfully determined and attained.\ Hay returned to Los Angeles in the winter of 1942 where he continued to teach Marxist courses on political economy. After Hay staged a successful "Big Sing Fest" in October 1945, local leftist organizations invited him to conduct "a ten-week educational program of people's songs." His first course, taught at Oleson Studios, was successful enough that Hay was soon teaching such courses in workshops all around Los Angeles (Licata 1978, 108). In 1946, he joined forces with his folk-music associates to form Los Angeles People's Songs, later affiliated with Seeger's People's Songs, Inc., in New York. Later that year, Hay developed a course called "Music, Barometer of the Class Struggle" for the Peoples' Education Center (PEC). The course was offered in 1947 through the Southern California Labor School, a successor to the PEC that in fact was actually the Hollywood Communist Party (Licata 1978, 108; Roscoe 1996b, 45). It was partially through the success of these and subsequent courses that Hay began to research homosexuality and to conceive of homosexuals as a repressed cultural minority. He began pondering ways by which homosexuals, such as the dozens he met on beaches and in bars or closer to home in Pershing Square, could be stimulated toward social action.\ One summer night in August 1948, having been invited by a man he met while cruising Westlake Park, thirty-six-year-old Hay attended a party of "gay" students (as he later called them) somewhere near the USC campus (Timmons 1990, 134). Hay proposed to the partygoers that they set about to organize homosexuals within some sort of club or society, and several seemed enthusiastic about the idea. In an afterglow, Hay wrote a proposal the following night calling for the formation of a homosexual organization named Bachelors Anonymous, but future meetings never took place (Roscoe 1996a, 4). Writing under the pseudonym "Eann MacDonald," Hay posed three primary questions whose answers he would pursue for the rest of his life: Who are the homosexuals? What is their purpose in life? And how can they negotiate within the parent society to make significant contributions as a group? (Licata 1978, 108–9). No copies of this original document survive, and nothing came of it for two years—that is, until he shared a later version with his new lover, fashion designer Rudi Gernreich.\ Hay's account of the influences and inspirations behind this now-famous prospectus calling for homosexual rights has been recorded in Radically Gay: Gay Liberation in the Words of Its Founder, edited by Will Roscoe (Hay 1996). Roscoe, who became an intimate friend of Hay's, traced these influences to several sources, some organizational and some cultural. While I will later elaborate on the structural and organizational aspects of Mattachine and some of its subsequent manifestations, it is also important to point to the cultural and literary influences that impacted the "Mattachinos," as they called themselves in the early days, for it is from these that Hay drew his conception of homophiles (and, later, gays) as a repressed cultural minority.\ Hay's first cultural model was the Native American tradition of the berdache, now often referred to as "two-spirit" in the anthropological literature. Hay first learned of the berdache in the early 1930s through reading a Modern Library compilation titled The Making of Man: An Outline of Anthropology, edited by V. F. Calverton (1931), which included articles by Edward Carpenter and Edward Westermarck (Roscoe 1996b, 47). Later, by the mid-1940s, Hay discovered the works of Marxist anthropologist Gordon Childe and the Boasian cultural anthropologists, especially Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict (Roscoe 1996b, 39). Hay was particularly inspired by the berdache described in Ruth Benedict's Patterns of Culture (1934). From Benedict, Hay envisioned the berdache as having "a reputation not only for excellence in crafts and domestic work, but in many tribes they were religious specialists as well" (Roscoe 1996b, 47).\ Hay was also inspired by the Kinsey report, which provided scientific proof that as many as 10 percent of the world's population regularly or occasionally engage in homosexual acts. A percentage of those were considered to be exclusively homosexual, and Hay believed they should be allowed the right to that existence: "Rather than a few isolated misfits lurking about the red-light districts of the largest cities, there were, in fact, millions of homosexuals—everywhere" (Hay 1996, 60). The trick was to organize them and focus their latent resources and energies on improving their status in society. A 1949 version of Hay's prospectus "described how we would set up the guilds, how we would keep them underground and separated so that no one group could ever know who all the other members were and their anonymity would be secured" (Katz 1992, 411).\ Through his studies, Hay came to believe in a primitive or primal matriarchy, a theory he publicly advocated as early as 1953 (Hay 1996). He believed that matriarchal societies had existed in Europe in the not-too-distant past, and these "folk" societies had their own form of ritualized berdache, which often manifested as the jester or ritual fool. Hay referred to this hypothetical personage as the "Folk Berdache" (Hay 1996, 110) and lamented that the homosexual's role in society had diminished considerably since "the whole Matriarchal cultural structure—known as the folk—was transformed and, thus, disappeared as a social force in history" (Hay 1996, 113). He began to envision organizing homosexuals into a revitalization movement, a call to arms for a people silenced and divided for millennia. He thought that, through teaching the history of such people, the homosexual minority could use the archetype of the folk berdache to hearken back to a time and place where it "was an accepted institution" and, "having no household and children to care for, could devote most of their time—aside from filling their own ... bellies—with the social, economic, and educational need of their communities generally" (Hay 1996, 114).\ Historian John D'Emilio wrote extensively on what life was like for homosexuals in the 1950s in his book Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940–1970 (1983). D'Emilio's book focuses on the active and relentless pursuit that police departments across the country carried out against homosexual persons and behavior. In 1950, President Eisenhower signed Executive Order 10450, which equated homosexuality with sexual perversion and barred all homosexuals from working in the federal government. During the next several years in Washington, D.C., more than 1,000 people were arrested per year for homosexual conduct. Other cites in which homosexuals were especially targeted in the 1950s include Baltimore, Philadelphia, Wichita, Dallas, Memphis, Seattle, Boise, Ann Arbor, and Los Angeles (D'Emilio 1983, 49–50).\ Since the 1950s, Harry Hay's philosophies have appealed to many, and after Mattachine he proceeded to found or inspire so many homosexual and gay associations that Vern Bullough dubbed him "the Johnny Appleseed of the American gay movement" (2002a, 73). Because of the magnitude of his influence on the homophile, homosexual, gay, and modern LGBT movements, one might consider Hay to have been a true prophet, one who influenced and was admired by many and who grounded his authority in a spiritual calling (Moore 1998, 146). At the outset, of course, Hay had to build his following one person at a time, and the inevitability of success was far from assured.\ The Founding of Mattachine\ After years of planning and forethought, Hay's project finally got under way when he met Rudi Gernreich, who for years was identified by historians only as "X" (Katz 1992, 409; Licata 1978, 108). The two met on Saturday morning, July 6, 1950, at a rehearsal at the Lester Horton Dance Theater, and according to Hay they fell in love almost immediately (Hay 1996, 314). Gernreich had survived the Auschwitz concentration camp. As Hay told Katz, "he and his family had come through some horrible experiences" (Katz 1992, 409). Gernreich became a talented and controversial fashion designer, most famously known for designing the women's topless swimsuit in 1964, and is also credited with the thong, circa 1979. His styles were as avant-garde as his ideas, and he is known in science-fiction circles for having designed the costumes for Space, 1999. At the time he met Hay, Gernreich tended to be socially aloof: "He wasn't a practicing member of anything" (Katz 1992). However, Gernreich thrilled to Hay's idea of a homosexual organization, and he prompted his clandestine lover to revive it yet again.\ Together, Gernreich and Hay visited homosexual beaches to circulate the Stockholm Peace Petition in protest of the Korean War. Between August and October 1950, they secured 500 signatures. At the same time, they asked beachgoers if they had heard of the Kinsey report. If so, would they mind attending discussion groups focused on Kinsey's data? As Hay told Katz, "We also used this petition activity as a way of talking about our prospectus ... some of the guys gave us their names and addresses—in case we ever got a Gay organization going. They were some of the people we eventually contacted for our discussion groups" (1992, 411).\ In November, prompted by Gernreich, Hay gave a copy of his prospectus, "Preliminary Concepts," calling for the unification of the "androgynes of the world" to Bob Hull, a student in his music class at the Labor School whom Hay suspected might be homosexual (Hay 1996, 315; Katz 1992, 411). Hull was a slender man, soft-spoken with a "chipper" attitude. He was a very talented organist, described by Jim Kepner as a "brilliant" musician who also composed his own music. Hay's hunch was right, and Hull was thrilled with the document. He called to ask Hay if he could bring two friends over to discuss the matter. These were Hull's roommate and ex-lover, Chuck Rowland, and Hull's current boyfriend, Dale Jennings.\ On November 11, 1950, the five met to discuss the matter at Hay's residence at 2328 Cove Avenue, in the Silver Lake district of Los Angeles (Hay 1996: 63–75, 358; Center for Preservation Education and Planning, 2000). As Hay remembers it, "Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, and Dale Jennings come flying into my yard waving the prospectus, saying, "We could have written this ourselves—when do we begin?" (Katz 1992, 411).\ Chuck Rowland once announced to his cohorts that he would willingly devote his life to the organization, provided they develop some "sound theory or philosophy" from which they could unify and proceed. Hay replied instantly, "We are an oppressed cultural minority." This comment profoundly impacted Rowland, who wholeheartedly agreed and continued to advocate on behalf of that minority for years to come. "To me, the gay culture idea was the cornerstone of the Mattachine," he later wrote in an October 1990 letter to Jennings. "You say we wanted to change the laws, and that was and is a worthy objective. But changing laws is almost meaningless unless one changes the hearts of men, both homosexual and heterosexual, and the heart change is, to me, what the Mattachine was all about." Gay journalist Jim Kepner would later refer to Rowland as "the founders' best organizer" (1994, 11).\ (Continues...)\ \ \ \ \ Excerpted from Pre-Gay L.A. by C. TODD WHITE Copyright © 2009 by C. Todd White. Excerpted by permission of UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.\ Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site. \ \

Preface viiAcknowledgments xvAbbreviations xixIntroduction 11 Mattachine (1948-52) 112 The Launch of One (1952-53) 283 Cleaning House (1953-54) 414 The Establishment of One Institute (1955-60) 625 Separation (1960-62) 936 Division (1963-65) 1167 Two Years of War (1965-67) 1378 The Founding of ISHR, HIC, and Christopher Street West (1965-70) 1759 Conclusion(s) 200Appendix A Significant Locations 227Appendix B Pseudonyms 230Appendix C Dramatis Personae 232Notes 235References 245Index 253