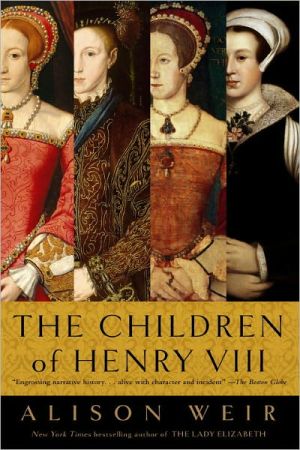

Queen Isabella: Treachery, Adultery, and Murder in Medieval England

In this vibrant biography, acclaimed author Alison Weir reexamines the life of Isabella of England, one of history’s most notorious and charismatic queens. Isabella arrived in London in 1308, the spirited twelve-year-old daughter of King Philip IV of France. Her marriage to the heir to England’s throne was designed to heal old political wounds between the two countries, and in the years that followed she became an important figure, a determined and clever woman whose influence would come to...

Search in google:

Isabella arrived in London in 1308, the spirited twelve-year-old daughter of King Philip IV of France. Her marriage to the heir to England’s throne was designed to heal old political wounds between the two countries, and in the years that followed, she would become an important figure, a determined and clever woman whose influence would come to last centuries. But Queen Isabella’s political machinations led generations of historians to malign her, earning her a reputation as a ruthless schemer and an odious nickname, “the She-Wolf of France.”Now the acclaimed author of Eleanor of Aquitaine, Alison Weir, reexamines the life of Isabella of England, history’s other notorious and charismatic medieval queen. Praised for her fair looks, the newly wed Isabella was denied the attentions of Edward II, a weak, sexually ambiguous monarch with scant taste for his royal duties. As their marriage progressed, Isabella was neglected by her dissolute husband and slighted by his favored male courtiers. Humiliated and deprived of her income, her children, and her liberty, Isabella escaped to France, where she entered into a passionate affair with Edward II’s mortal enemy, Roger Mortimer. Together, Isabella and Mortimer led the only successful invasion of English soil since the Norman Conquest of 1066, deposing Edward and ruling in his stead as co-regents for Isabella’s young son, Edward III. Fate, however, was soon to catch up with Isabella and her lover. Many mysteries and legends have been woven around Isabella’s story. She was long condemned as an accessory to Edward II’s brutal murder in 1327, but recent research has cast doubt on whether that murder even took place.Isabella’s reputation, then, rests largely on the prejudices of monkish chroniclers and prudish Victorian scholars. Here Alison Weir gives a startling, groundbreaking new perspective on Isabella, in this first full biography in more than 150 years. In a work of extraordinary original research, Weir effectively strips away centuries of propaganda, legend, and romantic myth, and reveals a truly remarkable woman who had a profound influence upon the age in which she lived and the history of western Europe.Engaging, vibrant, alive with breathtaking detail and unforgettable characters, Queen Isabella is biographical history at its finest. The Washington Post - Lisa Jardine Isabella emerges in this biography as a politically deft and intelligent protagonist, competent to intervene effectively in affairs of state. Weir makes a strong case for the historical importance of Isabella's decision to seize the English throne for her son, as the country slipped into chaos under her increasingly feckless husband's inadequate command. Though she cannot alter the record to make Isabella good and admirable, she does succeed in giving us an utterly compelling, gripping and believable portrait of a formidable medieval queen.

Chapter One\ On 20 May 1303, a solemn betrothal took place in Paris. The bride was seven years old, the groom, who was not present, nineteen. She was Isabella, the daughter of Philip IV, King of France; he, Edward of Caernarvon, Prince of Wales, the son and heir of Edward I, King of England.\ The Prince had sent the Earl of Lincoln and the Count of Savoy as his proxies, and during the ceremony, they formally asked the King and Queen of France for the hand of their daughter, the Lady Isabella, in marriage for the Prince of Wales. Consent was duly given, then Gilles, Archbishop of Narbonne, the presiding priest, required Isabella to plight her troth. Placing her hand in that of the Archbishop, she duly did so, giving her assent to the betrothal on condition that all the articles of the marriage treaty were fulfilled.\ This union had been arranged after tortuous negotiations to cement a lasting peace between those old warring enemies, England and France. Isabella’s father, Philip IV, known as Philip the Fair, was the most powerful ruler in Christendom at that time and also the most controversial. Not only had he been engaged in territorial wars with both England and Flanders for the past seven years, he had also, despite boasting the title of “Most Christian King,” become involved in a bitter conflict with the Papacy after imposing limitations on the Pope’s authority in France. This was to lead to his excommunication only months after his daughter’s betrothal.\ Philip’s war with Edward I was the result of a long-standing feud over England’s possessions in France. In the twelfth century, through the marriage of Henry II to Eleanor of Aquitaine, the empire of the Plantagenets, the dynasty that Henry founded, had extended from Normandy to the Pyrenees, while the royal demesne of France had been limited to the regions around Paris. By 1204, Henry’s son, King John, had lost most of the English territories, including Normandy, to the ambitious Philip II “Augustus” of France, and there were further French encroachments under John’s son Henry III, as successive French monarchs sought to broaden their domain. By the time of Edward I, all that remained of England’s lands in France was the prosperous wine-producing duchy of Gascony, the southern part of the former duchy of Aquitaine, along with the counties of Ponthieu and Montreuil, which had come to the English Crown through the marriage of Edward I to Eleanor of Castile in 1254.\ Philip IV, who was vigorously carrying on his predecessors’ expansionist policy, not surprisingly had his eye on Gascony, and in 1296, he invaded and took possession of it. There were two ways to settle a conflict: by military force or by diplomacy. Edward I wanted Gascony back, and Philip wanted to drive a wedge between Edward and the Flemings, who were uniting against him. By 1298, the two Kings were engaged in secret negotiations for a peace. Then Pope Boniface VIII intervened. In the spring of 1298, he suggested a double marriage alliance between France and England: his plan was that Edward I, a widower since the death of Eleanor of Castile in 1290, marry Philip’s sister Marguerite, while Edward’s son and heir, the Prince of Wales, be betrothed to Philip’s daughter Isabella, then two years old. Once this peace had been sealed, Gascony could be returned to Edward I.\ Boniface’s suggestion appealed to both parties; it conjured up for Philip the tantalizing prospect of French influence being extended into England and his grandson eventually occupying the throne of that realm; and for Edward I, it promised the return of Gascony and a brilliant match for his son. As the daughter of the King of France and the Queen of Navarre, Isabella was a great prize in the marriage market: no Queen of England before her had boasted such a pedigree.\ The deal was agreed in principle, and two weeks later, on 15 May, King Edward appointed Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, to negotiate both marriages. In March 1299, Parliament accepted the terms negotiated by Lincoln, and on 12 May following, plans were set in hand for the proxy betrothals. Three days later, the Earl of Lincoln, Amadeus, Count of Savoy, and the Earl of Warwick were appointed to act for Edward I and his son, and soon afterward, they departed for France. Edward I privately instructed the Count to find out as much as he could about the personal attributes of Marguerite of France, including the size of her foot and the width of her waist. The Count reported back that she was “a fair and marvellously virtuous lady,” pious and charitable.\ The Treaty of Montreuil, which provided for Isabella’s future betrothal to Edward of Caernarvon, was drawn up on 19 June, ratified by Edward I and the Prince of Wales on 4 July, and amplified by the Treaty of Chartres on 3 August. Under its terms, Philip was to give Isabella a dowry of £18,000, and once she became Queen of England, she was to have in dower all the lands formerly held by Eleanor of Castile, which were in the interim to be settled by Edward I on Marguerite; these amounted to £4,500 per annum. Should Edward I default on the treaties, he would forfeit Gascony; if Philip defaulted, he would pay Edward a fine of £100,000. On 29 August, at the instance of Edward I, the King and Queen of France gave solemn guarantees that the marriages would take place, and in September, Marguerite of France, then aged twenty at most, arrived in England and was married to the sixty-year-old Edward I in Canterbury Cathedral. Against the odds, this proved to be a successful and happy union, and produced three children. In October 1299, Philip IV finally ratified the Treaty of Montreuil. “When love buds between great princes, it drives away bitter sobs from their subjects,” commented a contemporary.\ In 1300, the French occupied Flanders, but two years later, they were humiliatingly defeated and massacred by the Flemings at Courtrai. Throughout this time, Edward I had continued to press for the immediate restoration of Gascony, but Philip would not agree to this until after the Prince of Wales had fulfilled his promise to marry Isabella, who was still too young to wed.\ By April 1303, Edward I was losing interest in the alliance and was beginning to look elsewhere for a bride for his son. At this crucial point, fearing a war on two fronts, Philip IV played his trump card and agreed to restore the duchy of Gascony to Edward without further delay; his intention was, as he reminded Edward II in 1308, that it should in time become the inheritance of his grandchildren, the heirs of Edward and Isabella. Edward I was now satisfied, and the Treaty of Paris, which officially restored the duchy, was signed on the same day that young Isabella and Edward of Caernarvon were betrothed. There would be further conflict between Edward I and Philip IV, but nothing serious enough to break this new alliance. Isabella was now destined to be Queen of England.\ Isabella was probably born in 1295. There is conflicting evidence as to the year. Piers of Langtoft says she was “only seven years of age” in 1299, which places her birth in 1292, the date given in the Annals of Wigmore. Yet she is described by both the French chronicler Guillaume de Nangis and Thomas Walsingham as being twelve years old at the time of her marriage in January 1308, which suggests she was born between January 1295 and January 1296. Given that twelve was the canonical age for marriage, and that in 1298, the Pope had stipulated that she should marry Prince Edward as soon as she reached that age, these dates are viable. In the same document of June 1298, the Pope describes Isabella as being “under seven years,” which places her birth at any time from 1291 onward. Furthermore, the Treaty of Montreuil (June 1299) provided for Isabella’s betrothal and marriage to take place when she reached the respective canonical ages of seven and twelve. So she must have reached seven before May 1303, and twelve before January 1308.\ It has been suggested that Isabella had already reached the canonical age for marriage in 1305, when she and the Prince of Wales nominated representatives for a marriage by proxy. This did not take place because of continued squabbles over Guienne, but the fact that these nominations were made has been held as evidence that Isabella had then reached, or was soon to reach, the age of twelve, which would place her date of birth around 1293. Yet this theory is contradicted by a papal dispensation issued by Clement V in November 1305, giving the young couple permission to marry at once even though Isabella had not yet reached her twelfth year and was at present in her tenth year. This suggests a birth date between November 1294 and November 1295. The waters are muddied still further by a decree issued by Philip IV in 1310, in which Isabella is referred to as his “primogenita,” or “firstborn,” which suggests that she was born in 1288 at the latest, as her eldest brother Louis was born in October 1289. This date conflicts with all the other evidence and is probably the result of an error on the part of the official drawing up the document.\ In conclusion, the evidence in the papal dispensations and documents and the Treaty of Montreuil is likely to be more reliable, and taken together, it supports a birth date between May and November 1295, which in turn is supported by the statements of Guillaume de Nangis and Thomas Walsingham. This would make Isabella seven years old at the time of her betrothal and twelve years old at the time of her marriage.\ Isabella grew up in a period when society regarded women as inferior beings. “We should look on the female role as a deformity, though one which occurs in the ordinary course of nature,” states a thirteenth-century edition of Aristotle’s Generation of Animals. “Woman is the confusion of man, an insatiable beast, a continuous anxiety, an incessant warfare, a daily ruin, a house of tempest and a hindrance to devotion,” fulminated the misogynistic Vincent de Beauvais in the thirteenth century. In 1140, the canon lawyer Gratian asserted that “women should be subject to their men. The natural order for mankind is that women should serve men and children their parents, for it is just that the lesser serve the greater.”\ The husband was his wife’s lord and master: he was to her as Christ to the Church. Thus, if a woman murdered her husband, she was guilty of petty treason and could be burned at the stake. He, however, had the right to beat her if she displeased him; indeed, it was “the husband’s office to be his wife’s chastiser.” He was not supposed to kill or maim her through such punishment, although, according to the legal code enshrined in the Customs of Beauvais, “in a number of cases men may be excused for the injuries they inflict on their wives, nor should the law intervene.”\ It was a woman’s duty to love her husband and show him due obedience. In 1393, an anonymous Parisian writer instructed wives to obey their husbands’ commandments, since “his pleasure should come before yours,” and he advised them to “cherish your husband’s person, give him plenty of attention, and the cheer of other delights, privy frolics, lovings and secret matters. Do not be quarrelsome, but sweet, gentle and amiable. And if you do all this he will keep his heart for you, and he will care nothing for other women.” The onus was always on the wife to maintain the stability of a marriage.\ In law, women were regarded as infants, so they had few legal rights. They were viewed as assets in the marriage market, chattels in property or land deals, or prizes in the game of courtly love, and their roles were very narrowly defined. When a group of noblewomen attempted to usurp male privilege and arrange a tournament in 1348, God “put their frivolity to rout by heavy thunderstorms and divers extraordinary tempests.” In the fifteenth century, one of Joan of Arc’s chief crimes was the adoption of male attire, which was seen as tantamount to heresy.\ Some highborn ladies were taught to read and write, but they were the fortunate few. In the thirteenth century, Philip of Navarre thought that generally women “should not learn to read or write unless they are going to be nuns, as much harm has come from such knowledge. For men will dare to send letters near them containing indecent requests in the form of songs or rhymes or tales, which they would never dare convey by message or word of mouth. And the Devil could soon lead her on to read the letters or”—even worse—“answer them.”\ Above all, in an age in which lineage and inheritance were paramount concerns, women were expected to be beyond moral reproach and to follow the virtuous example of the Virgin Mary. But because they were descended from Eve, who had committed the original sin, and were thus more likely to give in to temptation than men, they had to carefully guard their reputations. There was much comment on the frailty of women. “Wheresoever beauty shows upon the face, there lurks much filth beneath the skin.” This anonymous Parisian writer also observed that “every good quality is obscured in the woman whose virginity or chastity falters. Women of sense avoid not only the sin itself, but also the appearance of it, so as to keep their good name. So you see in what peril a woman places her honour and that of her husband’s lineage and of her children when she does not avoid the risks of such blame.”\ The Church taught that sex was primarily for procreation, not pleasure, and that intercourse was only permissible within marriage. Adultery was regarded as exceptionally sinful, especially on the part of a wife, for it jeopardized her husband’s bloodline. In 1371, the author of the Book of the Knight of La Tour Landry insisted that “women who fall in love with married men are worse than whores in brothels, and a gentlewoman who has enough to live on yet takes a lover does it from nothing but the carnal heat of lust.” A husband who caught his wife in adultery had the legal right to kill her.\ There were, of course, many women who circumvented the conventions. Many ran farms or businesses, or administered estates. Some even practiced as physicians. A few wrote books. And queens, by virtue of their exalted marital status, could exercise political authority and the power of patronage. Isabella would have been brought up to know exactly what was required of her as a daughter and as a wife, and she had before her the example of her mother, who was a queen in her own right.

\ From Barnes & NobleKing Philip IV of France cemented his peace with England in the most personal way: He sent off his only daughter, Isabella (1295?-1358) to marry King Edward II (1284-1327) of England. Only 12 at the time of the nuptials, Isabella bore Edward four children, but her marriage with her bisexual husband soured, and she eventually fled back to France, into the arms of Edward's archenemy Roger Mortimer. Together, the adulterous queen and her aristocratic lover raised an army and forced Edward to abdicate. The story of Edward's turbulent reign and its aftermath are complicated and mired in controversy, but royalty biographer Alison Weir navigates smoothly through all the court intrigues and rumor-mongering.\ \ \ \ \ Alida BeckerWeir (whose previous subjects include Eleanor of Aquitaine and Mary, Queen of Scots) is clearly at home trolling ancient archives for the housekeeping accounts, letters and chronicles that yield clues about 14th-century misbehavior. This gives her book an authoritative tone and lends some credence to her argument that Isabella, while a rapacious and ruthless product of a rapacious and ruthless age, was also a resourceful diplomat and a loving (if highly manipulative) mother, not exactly a model of medieval femininity yet hardly the blackhearted "she-wolf" of legend.\ — The New York Times\ \ \ Lisa JardineIsabella emerges in this biography as a politically deft and intelligent protagonist, competent to intervene effectively in affairs of state. Weir makes a strong case for the historical importance of Isabella's decision to seize the English throne for her son, as the country slipped into chaos under her increasingly feckless husband's inadequate command. Though she cannot alter the record to make Isabella good and admirable, she does succeed in giving us an utterly compelling, gripping and believable portrait of a formidable medieval queen.\ — The Washington Post\ \ \ \ \ Publishers WeeklyIsabella of France (1295?-1358) married the bisexual Edward II of England as a 12-year-old, lived with him for 17 years, bore him four children, fled to France in fear of his powerful favorite, returned with her lover, Roger Mortimer, to lead a rebellion and place her son on the throne and eventually saw Mortimer executed as her son asserted his power. Veteran biographer Weir (Eleanor of Aquitaine, etc.) battles Isabella's near-contemporaries and later storytellers and historians for control of the narrative, successfully rescuing the queen from writers all too willing to imagine the worst of a medieval woman who dared pursue power. Weir makes great use of inventories to recreate Isabella's activities and surroundings and, strikingly, to establish the timing of the queen's turn against her husband and her probable ignorance of the plot to kill him. Weir convincingly argues that the infamous story of Edward II being murdered with a red-hot iron emerged from propaganda against Isabella and Mortimer. (Her unlikely assertion that Edward escaped and lived out his life as a hermit is less believable.) Weir presents a fascinating rewriting of a controversial life that should supersede all previous accounts. Isabella is so intertwined with the greatest figures of her century and the next that any reader of English history will want this book. Maps not seen by PW. Agent, Julian Alexander. (On sale Oct. 11) Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Library JournalPopular British historian Weir (Eleanor of Aquitane) here seeks to establish a more sympathetic understanding of one of the most notorious queens in English history. Daughter of France's King Philip IV, Isabella (ca. 1295-1358) was unhappily married to England's gay or bisexual King Edward II. Though he fathered children with Isabella, Edward's real affections were for a series of male favorites, who gained untoward influence over affairs of the kingdom. Isabella, in the meantime, began an affair with Roger Mortimer, the Earl of March, and together they overthrew Edward, imprisoned him, and may have murdered him (against tradition, Weir disclaims Isabella's part in the murder). Their plan to rule England failed when her 18-year-old son, the future Edward III, seized and executed Mortimer and placed his mother under house arrest for the rest of her life. Weir believes that Isabella deserves credit for bringing about "the first constitutional deposition by Parliament of an English king," firmly establishing processes for parliamentary power over the Crown. She would have been appalled at the democracy that such a trend eventually produced, as Weir acknowledges. A lively work on a colorful period of English history; recommended for academic and public libraries. [See Prepub Alert, LJ 6/1/05.]-Robert J. Andrews, Duluth P.L. Copyright 2005 Reed Business Information.\ \ \ \ \ Kirkus ReviewsAnother engrossing biography of early English royalty from Weir (Henry VIII, 2001, etc.). Edward II's queen had been roundly scorned in her own time (1296-1358) and since by commentators, whose characterizations have ranged from "virago" and "Jezebel" to "She-Wolf . . . with unrelenting fangs." As is her wont, Weir goes for bold revisionism, aiming to "strip away the romantic legends and lurid myths" surrounding "this most vilified of queens." Her respectful portrait, aided by a generation of feminist historiography, depicts as understandable, even empowering, the very adultery and treason that tainted Isabella in the past. Refreshingly different, Weir's interpretation doesn't neglect the basic facts: Born in France to King Philip IV and Jeanne of Navarre, Isabella was betrothed to Edward at age seven. The marriage, celebrated when she was 12, attempted to settle long-standing conflicts between France and England. Edward was a hunk, and Isabella was reported to be the most beautiful woman in Europe, but theirs was hardly a match made in heaven. Edward, whose sexual proclivities ran towards men, virtually ignored his queen while lavishing attention on his friend Piers Gaveston. Eventually, Isabella returned to France, had an affair with exiled English traitor Roger Mortimer and gathered an army to overthrow her husband. Just who engineered Edward II's murder has always been something of a mystery, inspiring rumor and speculation in both the 1300s and the present. Weir's careful reconstruction of his death is especially valuable. Was Isabella behind the dastardly deed? You'll have to read the book to find out... Sure to reign as the definitive word on Queen Isabella for years to come.\ \