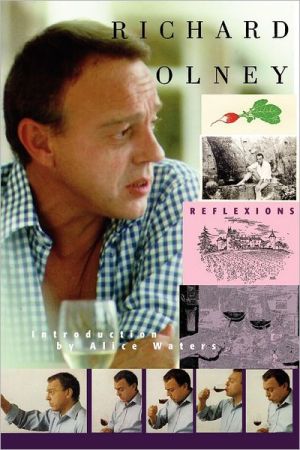

Reflexions

This book begins in New York in 1951 where Olney, a struggling artist, waited tables in Greenwich Village, then moves to Paris and weaves a magical description of food that becomes so real--as if you were actually there with Olney. It is a long-awaited story of the man who brought the simplicity of French cooking to the United States, and a statement about one of the finest and most important food professionals in the world.\ "Mr. Olney's influence in the culinary profession was...

Search in google:

This book begins in New York in 1951 where Olney, a struggling artist, waited tables in Greenwich Village, then moves to Paris and weaves a magical description of food that becomes so real--as if you were actually there with Olney. It is a long-awaited story of the man who brought the simplicity of French cooking to the United States, and a statement about one of the finest and most important food professionals in the world.

\ \ \ \ \ Chapter One\ \ \ 1951-1956 Paris. Clamart. Summers on Ischia. Travels in Italy and Greece. Magagnosc.\ \ \ It was the summer of 1951. I painted days and waited tables nights at 17 Barrow, a Greenwich Village restaurant whose cuisine wanted to be international, its atmosphere bohemian; on the walls were nostalgic travel posters from the '20s and '30s, the tables were lit by candles stuck into Chianti fiascos and, in the background, Edith Piaf and Billie Holiday sang of love and heartbreak. It fitted my mood and I liked the work, but Europe was on my mind. Father wanted his children to be happy but he could not understand why I had deliberately chosen a pattern of life that promised no stability. He believed, as a matter of principle, that we should be supported as long as we pursued the noble goal of higher education, but it had for long been clear that higher education and I were hopelessly incompatible; he decided that European travel might be important to a painter's education. I chose to sail on the De Grasse, the oldest and slowest of the French Line's ships, for its last voyage, 10 November. I was enchanted by the formal menus, the briny clean air that flowed through the open port hole at the head of my bed, the wondrous awareness of the ocean's vastness, the out-of-space, out-of-time renditions of swing, jazz, and French music hall tunes by the ship's orchestra and the rough sea, which nearly emptied the dining room and stretched our crossing from seven to nine days.\ My first meal in Paris was in a glum little dining room for boarders, in the Hôtel del'Academie, at the corner of the rue de l'Université and the rue des Saints-Pères. The plat du jour was "gibelotte, pommes mousseline"—rabbit and white wine fricassee with mashed potatoes. The gibelotte was all right, the mashed potatoes the best I had ever eaten, pushed through a sieve, buttered and moistened with enough of their hot cooking water to bring them to a supple, not quite pourable consistency—no milk, no cream, no beating. I had never dreamt of mashing potatoes without milk and, in Iowa, everyone believed that, the more you beat them, the better they were.\ The first few weeks, my days were spent mostly in museums and, for lunch, I ate as cheaply as possible. Good food was everywhere. A dollar bought 500 francs and could pay for a meal, including wine. Small family restaurants, with husband or wife in the kitchen, the other taking orders and tending bar, while the teen-age offspring waited table, were commonplace. The floors were scattered with sawdust and, for the regular clientèle, numbered pigeon-hole napkin racks hung at the entrance; the napkins were laundered once a week. Petit salé (brine-cured pork) cooked with lentils was a favorite main dish; others were gibelotte, pot-au-feu (called "boeuf gros sel" when served without its broth), poule-au-pot, potée (with sausage, cabbage, and aromatic vegetables), blanquette de veau, boeuf bourguignon, tripes au vin blanc or tête de veau, slow-cooking dishes based on inexpensive ingredients, which required only a talent for controlling the heat source to be perfect. I liked Chez Augustin, in the rue de Seine, a long, narrow room, lined on either side with banquettes and marble-topped, wrought iron tables, strung end to end. Before the entrance door was unlocked, the tables were set up with covers, bread, one of a variety of hors d'oeuvre and a carafe of red wine at each place. As the customers settled in, they began shuffling plates of hors d'oeuvre from one place to another, choosing what they wanted. Main course orders were taken, cheese and dessert followed and, on the way out, each client paid 700 francs. The wine was not good, but a bottle of good wine would have been no incentive to passing the afternoon in the Louvre.\ In the evening, I preferred seeking out, with new-found friends, bistrots with good cellars. One of the best in the quartier was the Chope Danton, at the Carrefour de l'Odéon, where habitués stood at the "zinc" downstairs to drink house wines by the glass and a spiral stairway led steeply up to the dining room. The tables were dressed with paper and the food was Burgundian or Lyonnaise in spirit. Except for a few Bordeaux and some of the grander Burgundies, the patron, Monsieur Moissonnier, chose his wines at the vineyards where they were raised in casks until the month of April following the vintage, before being shipped to Paris, bottled in the restaurant's cellars and drunk within the year. I have never drunk prettier Beaujolais than his Chiroubles, Saint-Amour, Fleurie or Côte de Brouilly.\ The hotel was a few minutes' walk from the crossroads of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, around which were clustered the Café de Flore, Les Deux Magots, the Café Royal, Brasserie Lipp and La Reine Blanche. I had no time to suffer from linguistic failings or solitude. At the Flore and the Deux Magots, English and American habitués table-hopped and a new-comer was instantly drawn into their insular society. A young English film-maker, Peter Price, asked if he might join me for coffee, then invited me to dinner at the home of cinéaste friends, the Lovetts (their names were spelled differently), from whom he rented a room. Charles Lovett was English, lean, languid and elegant; Thad was American, stocky, affected to be tough and thumped around in cowboy boots. They had a housekeeper-cook, described by Thad as a famous cordon-bleu. At table, cheap red wine was poured from exquisite antique decanters into crystal tulips. Their other locataire was Kenneth Anger, whose first film, Fireworks, was then enjoying a great success at the avant-garde French Cinémathèque. Kenneth offered me a room in the rue Jacob, which he rented but had abandoned at winter's approach for, amongst other inconveniences, it was unheated and had no running water. I moved in but not for long. Most nights, John Craxton, a young English painter, arrived to share my bed; we kept each other warm. He moved in a bucolic dreamworld, peopled with beautiful Greek goat herds. Soon he left for Greece.\ La Reine Blanche was a deep tunnel, lit brightly and crudely. Physically, it had no charm. The only feminine presence was Madame Alice, the patronne, an impassive mountain of stone, surmounted by a tightly pulled and smoothly sculpted mound of cold stone-grey hair. Her flesh was grey and she dressed in grey. But for a twitch at the corners of her mouth, Madame Alice's welcoming smile disturbed no muscle in her face. She rarely moved from the high seat before the cash register at the far end of the bar; when she did, she moved slowly, but she could effortlessly manhandle the roughest of her clients. She needed no bouncer. The bar, thickly populated by trade, was cruising territory. Beyond it were tables and booths where friends gathered; there, I met Sacha Neuville, Bill Aalto and Elliott Stein.\ Sacha, né Albrecht Niederstein, was then in his late forties. He had come to Paris from Berlin in the early 1930s and, during the war, had lived in the south of France with falsified papers in the name of Sacha Neuville, an identity that he chose to retain. He lived in the avenue de Ségur. A vast studio was hung with paintings by André Lhote and Moïse Kisling and a small kitchen was hung with heavy copper; Sacha was a fastidious cook. His days were circumscribed by habit and ritual, from the precise fragment broken from a rough cube of unrefined sugar for his morning coffee to the hour spent playing patience before dressing for the day, the cigarettes, meticulously rolled from tabac bleu in stickumless, tan papier maïs and lit by a temperamental antique lighter, visits to the flea market and to a shop in the rue Washington for freshly roasted moka, where the patron sternly advised his clients to use only Evian water for preparing his coffees, drinks at the end of the day with his friend, Robert, a second-hand book dealer in the rue Mazarine, who was more often with collegues at Juju's bar next door than in his shop, to the after-dinner coffee and glass of red wine at La Reine Blanche. At our first meeting, Sacha asked, "Have you met Jimmy Baldwin?" The name meant nothing to me. He said, "Well, he is out of town now, but you are bound to meet him as soon as he returns." Because the question recurred so often during the following months, I became conscious long before the event that "meeting Jimmy" was a major part of one's induction into life on the Left Bank.\ Bill Aalto, a disheveled, sentimental giant, who had lost a forearm in the Spanish Civil War and always looked as if he had just surfaced from a brawl, was a gentle poet who suffered cruelly from the infidelity of his muse. Volcanic eruptions after a drink too many had earned him the nickname, "Big Etna," which wicked friends promptly transformed into "Big Edna," and often simplified to plain "Edna" to fuel his rage. Bill was a loyal drinking companion. It was he who introduced me to Chez Inez, a club in the Latin Quarter where Inez Cavanaugh, accompanied at the piano by Aaron Bridges, sang beautiful blues.\ Elliott Stein, poet and editor of a recently defunct little magazine, Janus, had lived since 1947 in the Hôtel de Verneuil and suggested that I take a room there. Seen from the outside, the ancient building, at the corner of the rue de Verneuil and the rue de Beaune, was beautiful, architecturally sober and pure. Inside, the Corsican owners, Monsieur and Madame Dumont, three children and a kindly grandmother, who later retired to Corsica, lived on the ground floor, above which were five floors and twenty-seven rooms. Room no. 1 was rented out by the hour, many of the others were let to writers of various nationalities. Mine was banal and badly lit, but the daily rate was 300 francs and most of my time in the hotel was spent in Elliott's room, no. 27, a book-lined cocoon, whose windows, set deeply into the slanting walls, opened onto both streets. The only toilet was on the second floor, a "squat-john," or hole in the floor, furnished with torn-up newspapers and a violent flushing system, which encouraged one to stand outside the entrance before pulling the chain. Each room contained a sink but the hotel had no bath; the sheets were changed once a month and the minuterie was adjusted to illuminated phases so brief that one often arrived at a landing in the dark before pushing a button to light the succeeding flight of stairs. When I moved in, the first question asked by Madame Dumont was, "Do you know Jimmy? He lived here, you know, and, when he was sick, it was I, personally, who nursed him back to health by cooking porridge for him every day!" (Many years later, on a brief visit to Paris, I stuck my head in to say hello and found Madame Dumont simmering. "Did you know," she said, "that Jimmy was in Paris and he didn't even come by to say bonjour to me—I, who saved his life.")\ Elliott and I were rapidly recognized as a couple. However, no declarations of everlasting fidelity had been sworn and Elliott was determined to impose the concept, if not the fact, of his independence. His favorite method was to recount in lurid detail the antics at organized orgies that he attended, either with Harriet Sohmers, a tall, handsome American girl, who was always looking for trouble, or with an English film-maker, whose name I forget; I could never sift out the fact from the fantasy.\ Elliott, at a tender age, had devoured more literature than I could imagine absorbing in a lifetime. He was, then, methodically re-reading all of Henry James, but his greatest passion was the cinema. He disliked grade "A" films, admired grades "B" and "C" and, I think, considered King Kong to be the greatest film ever made. He, naturally, had much to discuss with Kenneth Anger and they became, for a while, great friends. Amongst Elliott's friends in the hotel was a self-styled "avant-garde playwright," Daniel Maroc, whose proudest possession was a notebook in which he ticked off the number of men he had seduced. They were nameless and without sentimental value. He cruised the streets nightly, bringing one, then another, to his room and, as each departed, another mark was added to the book. The number was into the thousands. Annette Michelson, John Ashbery, Otto Friedrich and Ned Rorem, with whom Elliott was working on a short opera, often came by.\ Peter Watson, the angel behind Horizon, the literary magazine edited by Cyril Connally, and the principal benefactor of the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Art) in London, came often to Paris to sit for a portrait, commissioned from Giacometti. Peter was immensely likeable and, in an elegant bird-of-prey fashion, quite beautiful, lean and angular with sharply drawn features. Giacometti, in frustration, wiped out the features after each sitting. Giacometti was intense. I've never met anyone so possessed, tortured and innocent. He seemed to be crying out for help and to believe that every banal phrase uttered over a passing drink might contain an important message.\ Elliott decided that my allowance was inadequate and that I should take a job cooking dinners for his friend, Tommy Michaelis, a middle-aged lawyer who loved being surrounded by young men. Tommy's first words, when I arrived, were, "Do you know Jimmy Baldwin?—No?—You must meet him as soon as he returns to Paris—he is a genius!" Once, Bill Aalto came to dinner but, mostly, the company was trade, pleasant enough but with limited conversation and indifferent to the food and the wine, which were gobbled and guzzled. I left after a couple of weeks.\ In February 1952, Peter Watson asked Elliott and me to spend a week with him in London. The visit coincided with the death of the King; London may never have been so packed, but the crowds had little effect on attendance at the National Gallery, where we were able to admire the Piero della Francescas in peace. We kept off the streets and made no attempt to eat in restaurants. I was surprised, after the lush French markets, to discover England still on wartime food rationing., Blue duck eggs were unrationed but chicken eggs and butter were rare. I cooked, we ate well, drank good wine and the conversatian was relaxed; it could not have been a nicer introduction to London.\ With the approach of spring, I intended to head for Italy. Elliott planned to join me later. Bill Aalto, who had spent a lot of time in southern Italy and, in particular, in Forio, on the island of Ischia, where his friend, Wystan Auden, held court, insisted that we pass the summer in Forio. Another friend, Bernie Winebaum, who was passing through Paris, enthusiastically agreed and both sent off letters to Auden announcing our arrival some months hence. I wanted, above all, to visit Florence but, because Kenneth Anger was leaving for Rome and had promised to hold me a room in his pensione, I began there. I put Kenneth on the train, with the drama that has always attended him: we lingered too long over dinner and, upon arriving at the quai in the Gare de Lyon, his train was pulling out; he managed to fling himself through an open door onto the platform while I hurled his suitcases in after him. A few days later, it was Bill Aalto who put me onto the same train. The restaurant in the Gare de Lyon, in which we had dinner, has since been named Le Train Bleu, a souvenir of the defunct Paris-Nice, all-sleeper, luxury train, once famous for its food. The high vaulted ceilings, with murals of plump goddesses and ponderous bearded gods flitting around in the clouds, looking very much like well-to-do citizens of the Second Empire, are wonderfully silly, the cuisine is comfortably bourgeoise and the wine list good.\ I was too impatient to arrive in Florence to do justice to Rome on that first trip. My clearest memory is of the Etruscan terracotta sarcophagus of the almond-eyed couple in the Villa Giulia. We ate at Ranieri, where the aging proprietor recounted the visits of Ronald Firbank, who contented himself with peeling a couple of grapes for his meal but tipped like a grand seigneur.\ Most of what I knew about Florenoe and the early Italian Renaissance I had learned from Mary Holmes, art history lecturer at the University of Iowa during the 1940s. She was everyone's favorite teacher and instilled in hundreds of students an enduring passion for the Italian masters of the 15th century. From the lecture podium, through clouds of cigaret smoke, she held the auditorium in a trance and, when lecturing on Masaccio or Piero della Francesca, she could never leave them.\ Upon arriving in the railway station in Florence, I checked my bags and began wandaring, aimlessly, until my steps led me to the church of Santa Maria del Carmine. At the left-hand entrance to the Brancacci chapel, in the right arm of the transept, the first thing one sees is the most moving expulsion from the Garden of Eden in the history of art. Masaccio painted it in 1427. This boy, who died before the age of thirty, had a vision whose power has never been surpassed.\ My friend, Lucia Vernarelli, with whom I had studied under Tamayo at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, was in Florence and had held a room for me, overlooking the Arno, at the Pensione Bartolini, a small family affair on the top floor of an old palace on the lungarno Guicciardini, at the foot of ponte Santa Trinità; pitchers of hot water were delivered to the rooms for morning toilets, but a bath had to be ordered in advance so that the wood stove in the bathroom could be stoked to heat the water. In the years to follow, I never attempted to stay elsewhere and, most often, Lucia was a fellow guest at the Bartolini.\ Lucia's friends were artists and writers. Except for Giovanna Crema, an adorable, high-spirited girl, whose lip often curled in contempt of middle class mores, and her companion, Mario who later committed suicide, my memory of them is vague—my Italian was inadequate and their English non-existent; we stumbled along in a sort of French. Usually we ate in a small restaurant, frequented by artists where Giovanna, who was seduced by the American habit of drinking orange juice for breakfast, insisted on having freshly squeezed blood oranges for dessert. To celebrate—anything was an excuse—we ate at Cammillo, a trattoria in borgo San Jacopo, a few stops from the Bartolini. This was before the official "D.O.C." laws (Denominazione di Origine Controllate) dictated that Chianti must be red and before red Chianti assumed pretensions to grandeur. The proprietor, Bruno, owned vines in the Chianti region and served his red and white Chiantis, fizzy and cool, in carafes. Cammillo was known for its bistécca alla fiorentina, a thick T-bone steak grilled over wood coals. I remember also their trippa alla f1orentina, thin strips of tripe, braised with white wine, tomatoes and oregano, sprinkled with grated Parmesan and passed beneath the grill. Late autumn, they always had fresh white truffles to shave over risotto or taglierini.\ Forio d'Ischia was a couple of hours' boat ride from Naples. The white, sandy beaches were vast and unpeopled. There was a small outdoor market. The butcher, who had no refrigeration, sacrificed one animal a week, which he called "carne"; it was neither beef nor veal or, in his view, it was both. I reserved the brain each week in advance; the meat was too fresh, but the tougher cuts made good stews. Each morning, a peasant led a nanny goat from door to door, squirting into a bowl the necessary amount of milk for breakfast coffee. The social center was the terrace of Maria's caffè. Inside, the walls were covered with magazine photos of her most famous client, signor Auden. Of course, Bill Aalto had given me a letter of introduction to Maria, a dumpy, bubbling, good-natured lady, who painted her face with abandon and dyed her hair jet black. Her business partner was her older sister, Gisella, an affectionate, motherly woman, who never gave a thought to her gray hairs, from whom I rented our house for the season. I met Auden on Maria's terrace and we spent a pleasant evening, while he reminisced about old friends, announced the imminent arrival of his friend, Chester Kallman, of Pavel Tchelitchew, whom he considered to be the greatest living painter, and, perhaps, of Brian Howard, "a brilliant and dear friend, but a lapsed poet," and described his pattern of living: writing poetry from 7 'til 10, correspondence from 10 'til noon, after which he Was free. He asked me to come around to his house the next day at noon. At the apéritif hour, I mistakenly assumed that I had been asked to drink a glass of the local white wine. Instead, he pulled several small hotel-breakfast jars of honey and jams from his pockets, explaining that he always carried them with him, should the opportunity present itself, and that he liked to smear the stuff on boys' cocks and lick it off. He wondered if I would like to try it. I declined. The air became abruptly hostile, I said good-bye and we never spoke again. A couple of days later, Chester Kallman, whom I had known in New York, arrived; he cut me dead. When Elliott arrived, I explained that we were social outcasts—he giggled. The only entertainment in Forio was Maria's terrace of an evening, for the most part observing the flirtatious, animal activity of the local boys; Elliott and I took a table on one side of the terrace, while Auden and Chester, surrounded by English professors, occupied the other side. One day, a note was delivered from Pavel (Pavlik to everyone) Tchelitchew, who, with his friend, Charles Henri Ford, had rented a house across the road, asking us to come for drinks. There were no preliminaries—Pavlik explained immediately that Wystan had warned him that we were out-of-bounds and that he must avoid us at all cost, which, as he said, with much chuckling and chortling, only whetted his curiosity. Pavlik was very funny—I never stopped laughing whenever we were together. He would say, with child-like glee, "Oooh! I have a big one, you know!" He attributed his great success with ballet dancers to "the big one." He bemoaned the cruel pitfalls of love—Edith Sitwell, he said, was hopelessly in love with him, which was a great bore, whereas he suffered agonies of unrequited love for Peter Watson. His letters, mostly about mystical concepts that he hoped to convey in his paintings, were written in a small hand, which diminished in size as it approached the bottom of the page, when he would begin turning the paper around, writing sidewise and upside down, smaller and smaller, a couple of times around, before turning it over, repeating the process and beginning another page. I saw him whenever he was in Paris, until his death, five years later.\ Tommy Michaelis planned to arrive on an early evening boat and spend a couple of days with us. The preceding day, I bought a mature, young cock from a neighbor, killed, plumed and cleaned it and put it into the ice-box to relax. The next morning, by miracle, a peasant came down from the mountain, peddling a crate of freshly-picked wild mushrooms. I recognized none of them, but they were beautiful and I bought the lot—more than half were Caesar's mushrooms (Amanita caesarea), some still enclosed in a fragile grayish white membrane (volva), the size and shape of a chicken's egg, others freshly opened, the half-sphere caps bright orange with lemon-yellow gills. The unopened egg-shapes, when split, present the compact, embryo mushrooms in a striking design of orange lines, white bands of flesh and yellow stripes, encircling the white stem. At this stage, or freshly burst from the membrane, raw, thinly sliced and seasoned to taste at table with olive oil, a drop of lemon juice, a pinch of fine gray sea salt and freshly ground pepper—or, larger, with the caps spread wide, anointed with olive oil, grilled over wood coals and seasoned at table—they are exquisite. Then, I didn't know what to do with them, so I threw them into a large pot with the chicken and a dab of olive oil, covered, and moved things around occasionally over very low heat. Tommy arrived at 11:30; he had missed the old steamer and hired a private boat. During its lifetime, the chicken had not been pampered, but it had run free, developed some muscle and tasted like chicken. Thanks to Tommy's lateness, it was meltingly tender, it tasted like mushrooms, the mushrooms tasted like chicken and the juices were heaven. Tommy and Elliott tasted nothing—they began to quarrel, for no apparent reason, the moment we were at table; before the meal was finished, Tommy left in a rage. Elliott appeared to be quite pleased with the evening's outcome; I was convinced that he had planned the rupture in advance.\ We left Ischia for a couple of months of dedicated tourism in Greece, Sicily and Tuscany. Then, one could wander freely in the Parthenon and the Acropolis was open 'til midnight on the night of the full moon, the night before and the night after. The bleached white monuments, washed in white moonlight, were other-worldly. I took off my sandals and was wandering barefoot around the Parthenon in this eerie atmosphere, when a guard, in garbled French, roughly ordered me to put my sandals on; he said I was showing lack of respect—whether for him or for Athena was unclear.\ A writer friend, who rather grandly claimed to have been poisoned in several Paris three-star restaurants, insisted that we eat in a restaurant in Piraeus, the Athens seaport, which, he said, served the best food in Europe. It was an odd place. Except for the staff, there were no Greeks present. The food was banal, but they had created the formula, a quarter of a century before the nouvelle-cuisine loonies launched le menu dégustation, of the non-meal—fifteen or twenty little dabs of unrelated foods, served in interminable succession, one after the other, the whole lot accompanied by turpentiny retsina wine, for a fixed price. One day we had lunch in a primitive workers' restaurant in one of the little streets near the foot of the Acropolis. The tables were oil-cloth-covered boards, supported by sawhorses, with benches to either side. The food, mostly stews and baked dishes, was on view and one had only to point to order. I forget what we began with, but we both pointed to a huge vat of snails, the same small, white shelled snails that are, misleadingly, called "limaces" in Provence and prepared "à la suçarelle." These were prepared in much the same way, first cooked in a court-bouillon, then simmered for a couple of hours in a ragoût of sausage meat, garlic, onions, herbs, tomatoes and white wine. They were so good that even the retsina was a pleasure-the price of the meal, translated from drachma, was less than fifty cents. I have never eaten better in Greece.\ Except for the stark, melancholy remains of Greek temples in Agrigento, a section of moulded plaster ceiling, which collapsed over our bed in a Taormina hotel room and left me limping for two weeks, and some spooky catacombs near Palermo, packed with remarkably well-preserved corpses, my memories of that first trip to Sicily are vague.\ (Continues...)

Introduction7 One 1951-1956 Paris. Clamart. Summers on Ischia. Travels in Italy and Greece. Magagnosc11 Two 1957-1960 New York. Return to Clamart48 Three 1961-1966 European tour with Byron and James. Solliès-Toucas. Cuisine et Vins de France59 Four 1967-1973 French Menu Cookbook. Liberia. Summer Cooking Classes, Avignon101 Five 1974-1976 Simple French Food. New York, Berkeley, San Francisco. French Wine Tour. Cooking Classes, Venice168 Six 1977-1982 Solliès-Toucas, London: The Good Cook212 Seven 1983-1985 Yquem. Paris, Bordeaux262 Eight 1986-1991 U.S. Yquem tour. Ten Vineyard Lunches. Romanée-Conti288 Nine 1992-1999 Provence the Beautiful, Australia. Lulu's Provençal Table. Good Cook's Encyclopedia. French Wine332 Afterword Summer 1999. Solliès-Toucas389 Biography397 Index404